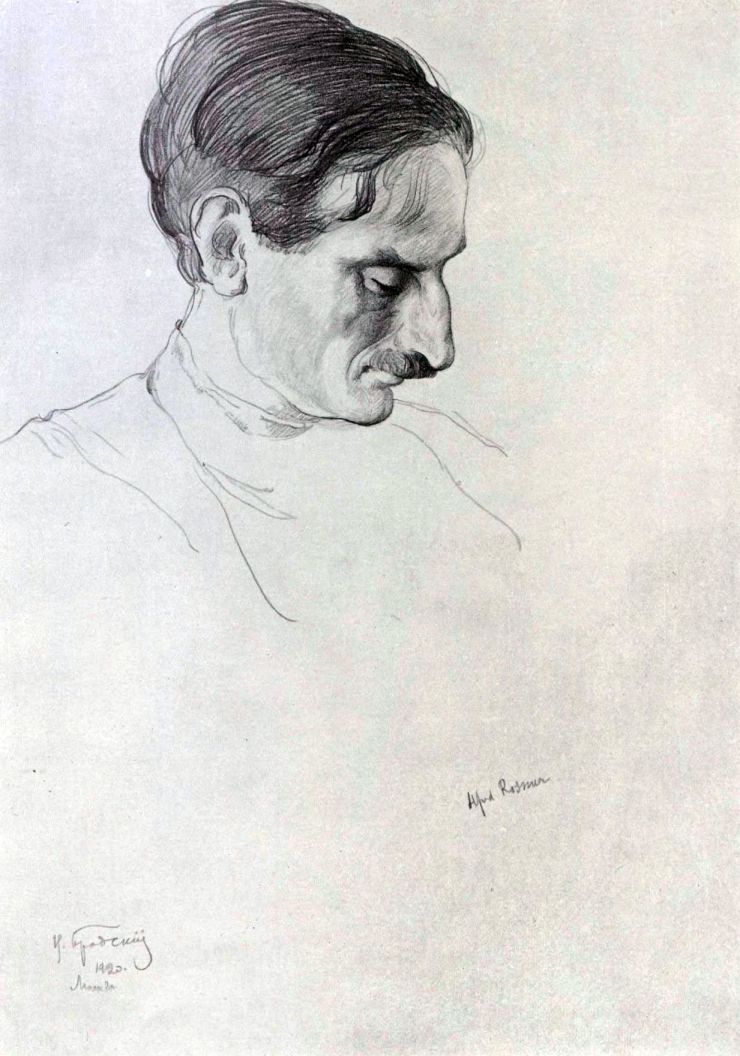

The early Communist movement began in many ways as a negotiation between revolutionary Socialists and revolutionary syndicalists, particularly in France and the United States. Alfred Rosmer was a leading French syndicalist who, along with Pierre Monatte supported the Zimmerwald Left during the war, and would also support the Bolshevik Revolution. On the leadership of both the Communist International and the Profintern, Rosmer played a key role as intermediary between the new Communist movement and syndicalists.

‘Necessity of Communist Activity in Conservative Trade Unions’ by Alfred Rosmer from The Toiler. No. 182. July 30, 1921.

From Bulletin Communiste. Translated for The Toiler by Mary Reed.

Shall Communists work in the heart of reformist labor organizations, or shall they form new organizations under their own management and with a platform on their principles?

The question did not come up for action in France until quite recently. The left elements faced it originally because, before the war, when the General Confederation of Labor was a revolutionary body, certain reformist organizations had already withdrawn. Thus the Miners Federation, where the reformists were in the majority, stayed outside the General Confederation of Labor for quite a while.

It was in the Federation of Metal Workers that proposals to split were first made towards the end of 1918. The defection of Merrheim, Federation Secretary, which occurred then, when he became reconciled to Jouhaux, Secretary of the General Confederation of Labor, whom he had been attacking steadily up to that time, aroused the indignation of many good comrades who proposed to boycott the Federation, and stopped paying dues. Particularly in the department of the Seine where the revolutionary elements were numerous, the question immediately assumed great importance. “Our money,” they said, “is being used against us, and to dupe the working-class; let us hang on to it, and use it for our propaganda.” Dual Unionism or Mass-Contact? But comrades who were no less indignant at the defection of the federal secretary, but who were more far-sighted, showed the foolishness of this argument. Doubtless the dues of revolutionists were being used to support the dangerous reformist activities of the Federation, but the problem must be examined from all sides, and this was the problem:

How could the Federation be turned back into revolutionary channels? How can it rid itself of leaders who have turned renegades? To leave the Federation would be to abandon the field to these men, enabling them to carry out their detestable policy, it would be to abandon the mass of organized workers, for it was certain that this would have a very limited effect, and only alienate the left elements from the mass.

The pro-split point of view was hotly and persistently defended especially by anarchist comrades, but it did not prevail. It was vigorously opposed by the group of the “Vie Ouvriere”, which had remained faithful to the principles of revolutionary syndicalism and had since the outbreak of the war, when the betrayal of Jouhaux and Co. had dragged the General Confederation of Labor into reformist channels, foreseen the formation of revolutionary syndicalist groups in all the unions, to carry on the struggle against the renegades of syndicalism and bring the General Confederation of Labor back to its revolutionary traditions. These tactics closely resemble those adopted by the second congress of the Communist International, when it called upon the communists to remain in the reformist unions, and form communist groups everywhere. It was these tactics which finally won out, and today the minority (revolutionary) unions are joined together by a body which is devoted to the coordination of their common activities. And, although proposals to split still are put forward from time to time, they have little chance of adoption.

Conditions in America.

The arguments in favor of syndical unity and against splitting are well known. The discussions which took place at the Second Congress of the Communist International and the principles which were adopted, brought them once more to the foreground. Special situations can always arise, as is the case, for example, in the United States. These special situations cannot be disposed of by the application pure and simple of the general rule. They call for special examination and special solutions.

In the United States the trade unions making up the American Federation of Labor of which the “yellow” Gompers is president, comprises only a small minority of the workers of that great country. This is just the state of things that these unions want, for they do not aim to unite all the workers, but on the contrary, only a small group, in order to form a sort of workers’ aristocracy. The means employed to attain this end consist, among other things, in a very high initiation fee and in the systematic elimination of all the unskilled workers, looked down upon by the new labor aristocrats and left defenseless to capitalist exploitation.

Nevertheless, recent events have shown that this state of things which has existed for many years is now being confronted with new currents. The domination of Gompers and his acolytes is being seriously menaced, and even in the heart of these ultra-reformist aristocratic organizations a revolutionary struggle is becoming possible. This is a very important fact.

But this situation has no equivalent anywhere else, while nearly everywhere in Europe the problem is the same, in England as in Germany, as in France.

Advantages of Remaining in Old Unions.

In organizations which include tens of thousands of workers, it is in these organizations that all true revolutionists must carry on the struggle. No doubt it is easier to bring about a split, to abandon the reformist unions and to create along side them revolutionary unions.

But the new unions thus formed are destined, by the very force of events to be of little importance as far as numbers go, and what is more serious, to have no influence on the mass of workers, and to limit themselves in advance to a policy which, however excellent it may be in theory, is in practice confined to a very narrow circle.

The struggle is harder in the old reformist unions, but nevertheless it produces better results. Under the present circumstances chances for action are not lacking. Instability of production and the ever-increasing cost of living throw the workers into frequent strikes. Then it is the duty of communists to make a lesson of events, to show that the struggle for mere increase in wages is an insufficient struggle because it is the capitalist system itself that must be attacked.

Moreover they find in these movements possibilities of showing up in a concrete way, the duplicity of reformist leaders who cannot conceal, in the course of their movements, their attempt to paralyze them, to dupe them, and to turn them off into blind channels to prevent them from reaching their logical and necessary conclusion. These leaders have basically the same point of view as the capitalists; like them they are trying to hold together the old world which the imperialist war shook up so violently and irretrievably distributed its equilibrium. The communists must tell all that to the workers; they must point out to them the lesson of the events which are now developing at such a great pace, at the same time that they are showing up reformist leaders and renegades.

But they must be convinced that they will have no chance of being understood by the mass of workers unless they keep in close contact with this mass, and carry on the struggle with it, in the same unions. It is on this basis that they can carry on their activities with maximum results.

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n182-jul-30-1921-Toiler-rsz-chronAM.pdf