A superlative accounting of among the most important strikes of the first decade of the last century from Louis Duchez, who knew the area and its workers intimately. An Ohio-born coal miner and proletarian intellectual; a poet, an organizer, a journalist, and a revolutionary Socialist who played a leading role in our movement during his too short life, dying at just 27 in 1911. In 1909, strikes convulsed the Pittsburgh area towns of McKees Rocks, Butler, New Castle, and Presston as thousands of largely unorganized, immigrant workers took on the mighty Pressed Steel Corporation in a bloody fight for union recognition, better working conditions, wage increases, an end to inhuman housing conditions, and dignity. The I.W.W. would come to lead this heroic strike, perhaps its most prominent to that moment, to victory. Those victories brought the wobblies to prominence and the attention of many Eastern workers. As usual, with ISR it is illustrated with one-of-a-kind photos. It should be read together with Duchez’ report from the September ISR. A classic and wonderful introduction to militant labor’s potent pre-war movement. It is also a reminder of what our class lost when it lost comrade Louis Duchez.

‘Victory at McKees Rocks’ by Louis Duchez from International Socialist Review. Vol. 10. No. 4. October, 1909.

IN this article the writer is not going to give much space to a recitation of the crimes of the capitalist class at McKees Rocks and the other strike points in Pennsylvania. It is unnecessary. The capitalist press has done that more effectively—regardless of the motives that may have prompted them—than he is able to do. The class struggle is a historic fact and the diametrically opposed interests have long ago been proven. Such practices as were exposed during the last few weeks are only the logical result of the capitalist system of society at this stage of working class activity.

Readers of the Review want something more than a mere account of the cruelties of the Pressed Steel Car Company. They want to know something about the spirit and growth of solidarity and industrial organization among the striking wage slaves in Pennsylvania.

For the strike at McKees Rocks has been won. In spite of the tremendous odds against the men they have conquered in this battle against the Steel Trust. Not long ago we read in the papers that not one striker would be taken back at the mills. But they have been taken back. The pooling system has been abolished. They have gained a 5 per cent, increase in wages with an additional 10 per cent, within 60 days. Half-holiday Saturdays and no Sunday work. Grafting bosses have been “fired” along with all scabs. The shop rules have been revolutionized and the changed conditions afford employment for 1,000 more men. Most important of all, the workers have already built up during the struggle a revolutionary union of over 4,000 members, who thoroughly understand there will be no written agreement with the company and that a recognition of the union is not to be desired. Nor is this necessary. Craft lines have been obliterated and craft union organizers have been “passed up” with suspicion.

It is true that public sentiment was with the men, but it is also true that they have beaten the company in tactics at every point. And in writing up the account of the struggle, it is to this phase of the situation that the writer wishes to confine himself.

The strike began with, apparently, no organization among the men. Chaos seemed to prevail. Sixteen different nationalities were represented. Among them were: Americans, Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Slavonians, Croatians, Polanders, Turks, Lithuanians, Russians, Greeks, Italians, Armenians, Roumanians, Bulgarians and Swiss. And the militant industrial unionists, who had training in the struggles in Europe—notably in Germany, Hungary and in the Russian revolution—played a very important part. Socialist leaders followed and established, with the aid of the industrial unionists, a remarkable discipline. Political propaganda, however, was useless among these men, because the fight was an industrial fight, and four-fifths of the strikers were not enfranchised anyway. Their shop minds could not get away from the mill—they wanted shop action.

A committee was elected known as the Big Six, only two of whom were revolutionists. The others were “pure and simplers.” These men ran the commissary store house, warned the men against violence and helped conduct the big meetings on Indian Mound. But so far as a knowledge of revolutionary tactics in a struggle of that kind was concerned, they knew nothing, although their intentions were of the best.

At the beginning of the strike, because of the many different nationalities, with nobody to bring them into a mutual understanding, there was much confusion. But a few men, who had been industrial unionists in Europe, got together, elected a committee among their own number and quietly, and without credit, planned the system and tactics of battle, put into operation methods of warfare, new in the history of labor wars in the United States.

Too much credit cannot be given these men, who went about forming an I.W.W. organization among the strikers. And the strikers found they had those among their own ranks who thoroughly understood the class struggle and up-to-date tactics in industrial unionism. But they were unable to make themselves understood.

This phase of the difficulty was overcome by securing interpreters and speakers and throwing the power and experience of the I.W.W. into the struggle. It is well to note in this connection, also, that four members of the Big Six committee represented only 1,000 of the strikers, while the two revolutionists on the committee represented nearly 5,000 men.

When it was learned that the controlling element of the Big Six was, consciously or unconsciously, reactionary and seemed to be at sea in dealing with the situation, an Unknown Committee acted in all cases of emergency. It was this committee that established the picket system, the signal system and the watch system which was so effective in keeping scabs out a few weeks ago. Among the foreigners this committee was known as the “Kerntruppen,” a term much in vogue in the military system of Germany. It means a choice group of fearless and trained men who may be trusted on any occasion.

This committee issued orders to the Cossacks in black and white, it is reported, after the killing of Horvath, one of their number, on August 12th, stating that for every striker killed or injured, a trooper would go. And they meant what they said, as is proved by the death of Deputy Sheriff Harry Exley and two troopers who went down in a riot on August 22nd with several strike breakers and some of the strikers, also.

It is also reported that the strikers could have killed every trooper if they had so desired, but they only resisted the violence meted out to them. The papers say the strikers and troopers are now on good terms and it is probable that no more rioting will occur. This Unknown Committee and the troopers know why. There has been an “understanding” between them that is more “sacred” than a contract between capital and labor by a long way.

On August 29th, a report was circulated that the bodies of three imported strike breakers, who died as a result of rotten food and brutal treatment, were cremated in one of the furnaces. Nobody doubts that they were cremated. Perhaps several poor workmen were gotten rid of in the same manner. When it is known that the dry bones of three foreigners were found under scrap heaps where they had lain for months in this same plant, it is easy to believe almost anything that may be told of that hell which is well-named “The Slaughter House.”

While still unproved, it is believed that the three bodies, cremated August 29th, were those of men who had been thrown alive into a hot furnace.

The Unknown Committee know how sixty strikers volunteered to hire out as strike breakers and go into the plant in order to get the scabs out. This was done. These sixty men were in the plant on the night the three foreigners were cremated. This much is known. But in the scrimmage, quick action was necessary and several went in who did not leave their names and were unknown outside their own friends.

At this writing the government is carrying on an investigation of this case, but there is no doubt in the minds of those who have been in close touch with events from the beginning, that the three cremated foreigners were three of the sixty volunteers.

Lack of space forbids a full description of the class war carried on in this little corner of the country. The tactics employed by the strikers at McKees Rocks, it is true, would soil the lady-like sensibilities of John Mitchell and Sammy Gompers, who love to sing the song of “identity of interest.” But the men acted on a full recognition of the cold hard facts and right in line with the words of A.M. Stirton, when he said:

“Whatever line of conduct advances the interests of the working class is right, and whatever line of conduct does not advance the interests of the working class is wrong.”

But the tactics employed by the men at McKees Rocks were not of their own choosing. Those of the master class have been more bold and cruel than the workers have yet, collectively, been fearless enough to employ. The workers did what their knowledge of strike warfare and class warfare compelled them to do.

It was not the workers who started the riot on the night of August 22nd, when a large number of people were killed and wounded. The Pressed Steel Car Company started that riot. The methods employed by the company were so brutal and barbaric that even the capitalist papers of Pittsburg exposed them. It is commonly known that Deputy Sheriff Harry Exler, the Cossacks, and a bunch of wharf-rats and hoodlums from Pittsburg and New York, started the trouble. They wanted to make an opportunity to mow down the wage slaves of “Hunkeytown.” Every method conceivable was employed to open up this opportunity. It is unnecessary to repeat them. But the workers refused to stand by and permit themselves to be starved, clubbed and shot to death!

The capitalist press stated that President Hoffstot wanted to see a charge of dynamite placed under the Pressed Steel Car Works, his object being to throw the blame upon the strikers and get rid of the old, worn-out plant and erect a newer and improved one.

A few days ago, Frank Morrison, of the A.F. of L. made the statement (and his is the organization that refused to have anything to do with the strikers) that the McKees Rocks strikers were an ignorant lot of foreigners. This is wholly false. Since the I. W. W. organized them, we learn that a large number of the men have been revolutionists in Europe. Many of the Hungarians took part in the great railway strike of Hungary. Three men were in the “Bloody Sunday” carnage in St. Petersburg. Participants in the Switzerland railroad strikes were there and several Italians who took part in the great resistance strike of Italy. Also there were many Germans with cards from the “Metallarbeiter Verband” (Metal Workers’ Industrial Union) of Germany, Austria, Denmark and Sweden. Besides there were many members of the socialist parties of Europe, and others who are members of the socialist party of America.

During the fight these men were to be found in “the hollow” in some private house laying the plans of battle. We do not belittle the daily mass meetings on Indian Mound. They were very effective in keeping the workers together and informed in regard to the situation, even though they were sometimes addressed by men and women who had practically no knowledge of the labor movement and the real requirements of the McKees Rocks situation.

But the strikers wanted something besides advice to refrain from violence and to abide their time. They wanted to know ways best fitted to meet the shrewd and heartless schemes of the company, and these things could not be shouted from the hill-tops. But the Unknown Committee in the valley laid the plans. So we can see that these strikers are not the mob of men the A.F. of L. would have us believe.

At the beginning of the strike, it is true, they had no organization. But this was because they had had no plan of organization and nobody to do that work, a great work with the men divided by sixteen different tongues.

But the I.W.W. brought these men together. Militant men who were able to speak the different languages carried the message and the men were eager to accept it.

On August 15th, the I.W.W. advertised a mass meeting to be held on Indian Mound. Large posters printed in five different languages were displayed. Eight thousand men attended the meeting—nearly all strikers, and many railroad men and trade unionists and laborers from Pittsburg.

William E. Trautman first addressed the meeting in English and German, after which the men were parcelled off in lots. Nine different nationalities were spoken to—besides these two—and to each man his own tongue.

To Ignatz Klavier, a Polander and member of the Socialist Party who speaks five languages fluently, much credit is due for enlightening the McKees Rocks strikers on the principles of industrial unionism. It was Klavier who, during the second week of the strike, brought out clearly the distinction between the A.F. of L. and the I.W.W. He was ably assisted by Henyey, a Hungarian, and Max Forker, a German.

A wonderful spirit of solidarity was shown by the trainmen of the Pittsburg, Ft. Wayne and Chicago and on the Pittsburg and Lake Erie roads—the only railroads running into McKees Rocks, when the trainmen refused to haul scabs to the plant. This is the first time in the history of labor troubles in the United States that this has been done. This was another example of the tactics of industrial unionism directly due to I.W.W. propaganda and education. Not only did the railroad men lend their aid to the strikers but the crews on the two company steamers, “The Queen” and “The Pheil,” refused to haul the scabs. This also is due to the work of the Unknown Committee and the great wonderful spirit of solidarity that is spontaneously stirring the wage slaves of the world. Even the school children of “Hunkeytown” refused to attend school until the strike was settled.

In this connection, it is interesting to learn that ten of the sixty strikers who hired as strike breakers, went into the plant and later escorted the 250 scabs out, on August 27, presented cards showing they were members of socialist parties. It also developed that all ten had military training.

In Butler.

The situation in Butler is much the same as it was last month. A Polish priest there urged the men to go back to work, and they did. This is not, however, the cause of the abrupt ending of the strike. This was due to the misunderstandings among the men of different nationalities and because there was nobody on the ground who understood industrial unionism, and who could bring them to a mutual understanding. Now the men are back at work, while the sixty most active rebels have been victimized. But they are rapidly being organized and will doubtless come out again within a few months.

The conditions at Butler are as intolerable as they were at McKees Rocks. One big difference is that in Butler there are no large capitalist political papers with axes to grind. It has developed since the men returned to work, that when the Cossacks charged the town, three of the strikers were stripped, tied to posts and beaten into in sensibility. Affidavits are being secured to prove this. The lives of the workers in the shops and in their shanties are just as miserable too as were those of the slaves of “The Slaughter House.”

At New Castle.

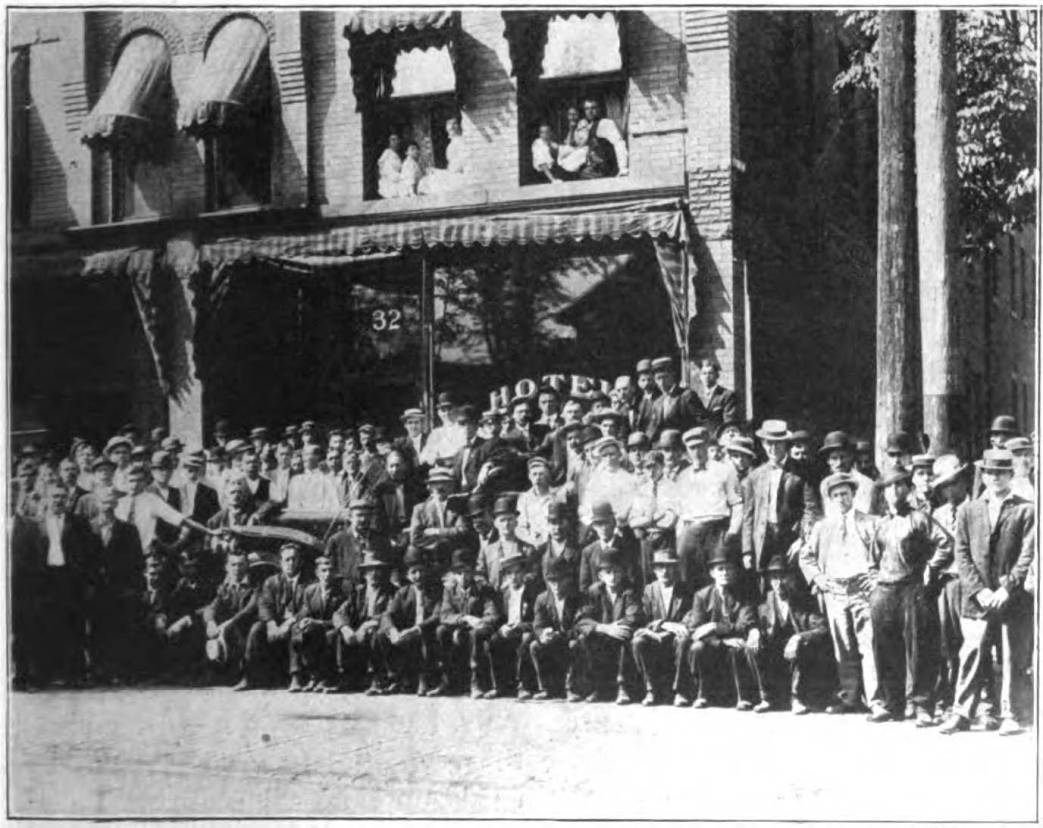

In New Castle the situation is almost unchanged. Practically no old men have gone back to work. On August 23rd, when the strikers marched down to their pickets’ tents near the mill to have this photograph taken, they were charged by the Cossacks and clubbed right and left. Several of the men were badly hurt although the 300 strikers were as peaceful as a funeral procession. Not one man in the crowd carried a gun. But the trouble at McKees Rocks demanded troopers, so the Cossacks have left New Castle.

The exposure of the county sheriff on the part of the Free Press (the official paper of the Lawrence County socialists) did more than anything else to chase the Cossacks out of town. But the strike is not over yet in New Castle. The men are becoming restless and dissatisfied with the actions of the Amalgamated leaders. They say there is not enough life in the fight there, and they want the independent union mills called out.

Railroad men in and around New Castle are kicking against hauling scabs into the city, but the officials of their organizations refuse to allow them to do anything. However, at a meeting of the local Amalgamated Association September 4th, a request was sent to President McArdle of the Amalgamated men to use his power to urge the head of the railroad men to listen to the appeal of the local railroad men in New Castle.

At South Sharon, Struthers and Martins Ferry the strikers in the tin industry are still holding out and the spirit of solidarity is growing stronger. Only the shell of the old organization stands in the way. The Wheeling Majority, a trades assembly paper, has come out for Industrial Unionism with a ringing editorial “For One Union.” Its news columns are full of good stuff.

In South Sharon a joint delegation from the Amalgamated and Protective Association has declared for industrial unionism. A manifesto has been issued from that place calling for a district convention for the purpose of going over into the I.W.W.

The most remarkable thing about these Pennsylvania strikes is the spirit of solidarity among the men. The workers are not concerned about the name of the organization. They are after the real thing and they know the A.F. of L. hasn’t got it to give. The writer predicts that within a few months, several big mills and mines in this part of the country will be out on strike and in open revolt against the master class. The winning of the McKees Rocks strike will be the spark. If our socialist press only had the insight and courage of conviction to point out where the revolutionary and constructive movement of the workers is when this uprising takes place!

In several places among the steel men and the coal miners of Western Pennsylvania locals of the I.W.W. have been organized and the membership is rapidly increasing. In New Castle an I.W.W. relief station has been established and is conducted by girls who worked in the tin mills, under the supervision of Charles McKeever, who is district organizer of the I.W.W. and secretary of the Local Lawrence County Socialist Party.

Several concrete lessons are to be learned from the McKees Rocks strike:

First, there is the fact that it is not necessary to organize a large percentage of the workers into a revolutionary industrial union in order to handle the Social Revolution. The writer believes that 10 per cent, of the workers organized in that form of an organization will be able to handle the situation. For instance, if the mining industry, especially the coal miners, and part of the transportation were industrially organized along revolutionary lines imagine what could be done! Why the supply of raw materials could be cut off and industry paralyzed at once.

During these Pennsylvania strikes we have had a sample of the possibilities along this line. In McKees Rocks with no organization and a confusion of tongues we see a big organization spring up and a strike won against the largest corporation in the United States. Not only that, but we find railroad men and steamship crews refusing to carry scabs. The rank and file of the working class is revolutionary enough to bring about a social revolution next week. What is necessary is the machine through which this revolutionary energy can manifest itself in unison. The leaders of the old time unions are as yet in most instances in the saddle, but they are being pushed aside and ignored by the revolutionary spirit and activity of the workers who will not be hoodwinked much longer.

In the second place we learn that it is not necessary to upset a man’s religious belief first before making a revolutionist out of him. In McKees Rocks and Butler we see this finely demonstrated. When the strike began foreign priests interfered. They knew very little about the labor movement, though they did know the revolutionary difference between the A.F. of L. and the I.W.W. In Butler, however, when the men were being organized a priest threw up his hands. He interfered with one of the largest meetings that was held there, and told his parishioners that the I.W.W. was a socialist organization and that they should join the A. F. of L. At any rate, a large percentage of his membership has left the church and, it is said, they are leaving him and his religion in such numbers that he will have to disband and hunt another parish or go into the car shops and work beside the men he tried to betray. In McKees Rocks, also, the faith in priests is waning rapidly. The poor workers say it’s bread, not heaven, that they need just now.

Lastly, the most important thing demonstrated in these strikes is the fact that the political power of the working class is wrapped up in the economic organization, also that the revolutionary movement of the workers is on the industrial field. In McKees Rocks we have seen how a group of striking foreigners, because they stood firm, compelled the government to investigate conditions there. Why doesn’t the government look into the conditions prevailing at other places, such as Butler, where they are just as bad as they are at McKees Rocks! It was because there was no economic organization carrying on the fight at that place. Without economic organization the workers are helpless and their groans are unheeded by the master class, but once they assert their solidarity in the shops the entire governmental machinery may be brought under their control.

It is in the shop and in the mill and in the mine that the power of the workers lies and it is there it must be organized. Instinctively the worker, who has been brought under the modern machine process, realizes that. He lives and moves and has his being in the shop, not in the legislative halls. He wants direct action and there is the only place he can get it. Moreover, it is there where the foundation of the new society must be laid. The revolutionary and constructive movement of the workers is in the industrial union. All other movements, including the political, have been but theoretical or laboratory tests, all right as a passing stage, but something that must give way to the real, constructive movement.

The workers of the world, I believe, may well turn their eyes to America as the opening scene of the last struggle with the master class. All signs indicate that the great worldwide movement of the world’s toilers will find its origin on American soil. The industrial process is more highly developed here than in any other country. Because of the fact that our capitalist class has accumulated its wealth so rapidly that it still retains its middle class attitude of mind, it is more despotic, more brutal and more intolerant, and with all, more ignorant than the master class of Europe. Then the progressive and revolutionary blood of Europe has been driven to this country and we are not hampered with the clannish traditions of the lands across the Atlantic.

Besides, the working class, once aroused, in this country will want direct action. Not only that but a large percentage of the workers here have no vote, any way. The principal reason why the workers of this country will not look to the political state for the redress of their wrongs is that the state is not their direct enemy as is the case in Europe, where the industrial life of those countries is more or less directly controlled by the political state of the masters there. Great things, indeed, may be expected from the working class of this country in the near future.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v10n04-oct-1909-ISR-gog.pdf