As it was, so it is. Protecting the position of human being as capitalist property is not just its tradition, it is its raison d’etre. Elizabeth Lawson with an excellent history of the Supreme Court’s central role in the institution of American slavery.

‘The Supreme Court, a ‘Citadel of Slavery” by Elizabeth Lawson from The Communist. Vol. 16. No. 4. April, 1937.

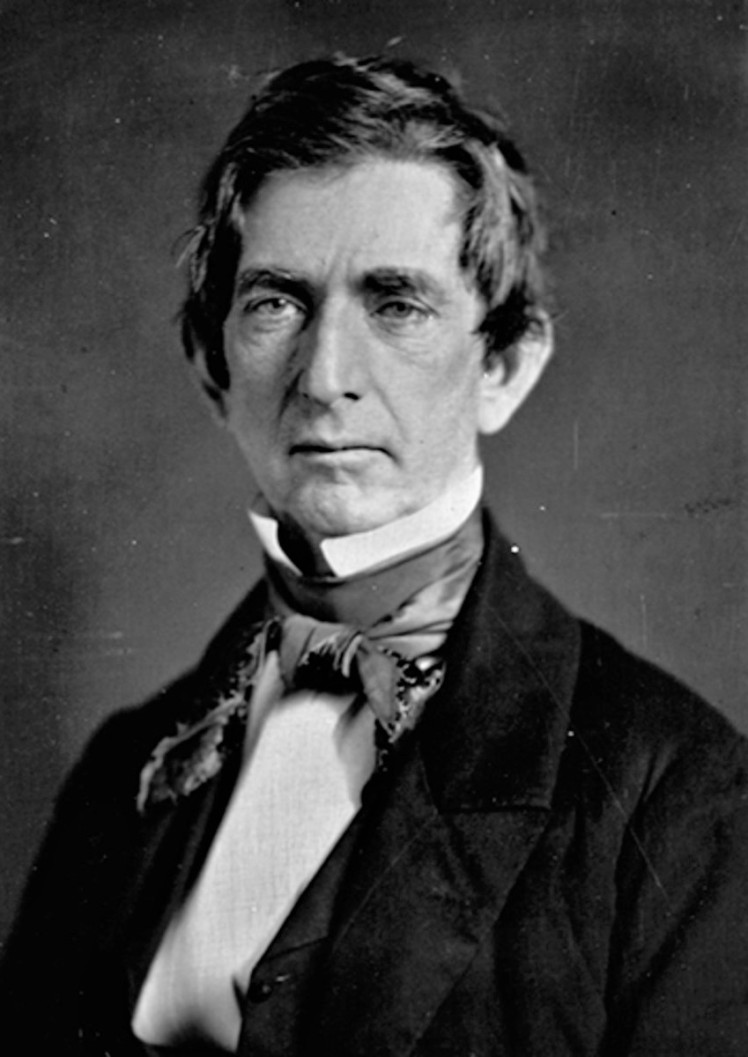

AMONG the most pliant and powerful tools of the American slavocracy was the United States Supreme Court. From the floor of Congress, Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire denounced it as “the citadel of slavery”. Between 1825 and 1858, the highest court rendered eleven decisions reviewing basic principles of the slavery system; each of these decisions was in complete harmony with the interests of slave-owners. That the opinions were, in several instances, mutually contradictory; that justices affirmed what they had previously denied; that they tortured principles of law to make them serve the convenience of the moment—all this renders untenable the theory of the Supreme Court’s political innocence.

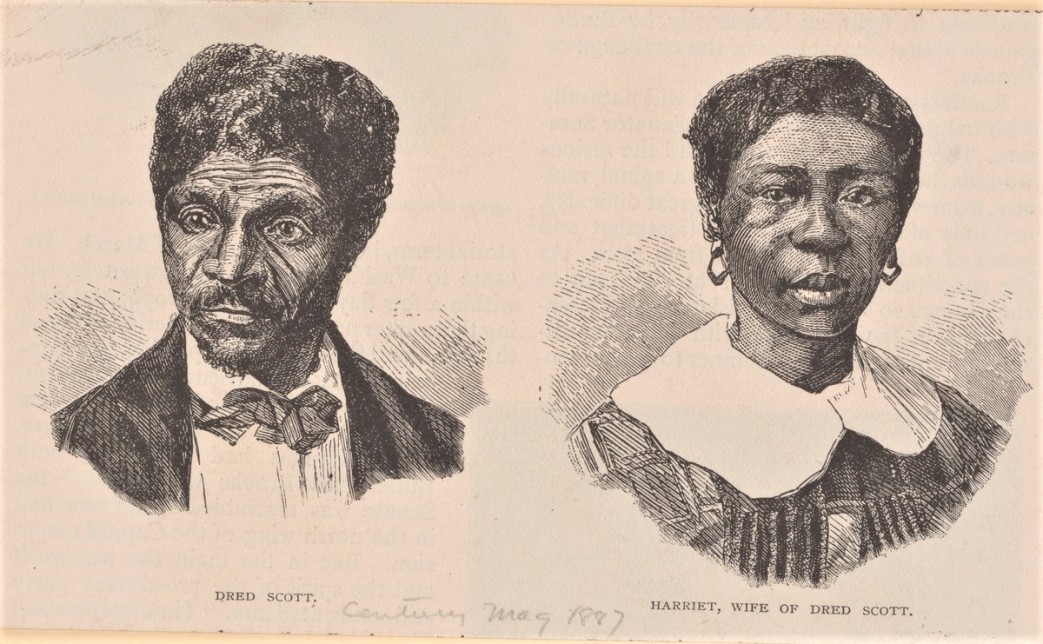

Of the eleven decisions touching on slavery, four dealt with the African slave trade; four with federal and state fugitive slave laws; and three with the status of slaves who, though not fugitives, had resided temporarily on free soil. Of this last group of cases that of Dred Scott concerned also the legality of slavery in the vast territory not yet admitted to statehood. The astounding Dred Scott opinion was the culmination, the most rounded expression, of the pro-slavery theories of a court which, in the course of three decades, constructed the legal framework within which the slavocracy could function to best advantage.

The composition of the court during this period gives evidence of deliberate “packing” by the slaveholders. By the Act of Congress of 1837—five years after the attempt at nullification by South Carolina marked the slavocracy’s political maturity—the free states, with a population of almost 10,000,000, were to have but four circuit courts, while the slave states, with a white population of only 4,500,000, were to have five. Free states admitted to the Union in later years were granted no representation on the Supreme Court.

Through control by the Judiciary Committee of the Senate, there were appointed, for the minority of circuits in free territory, judges who—with a few notable exceptions—reflected the opinions of the Northern commercial and banking aristocracy, in alliance with the slave-owners. Thus, at the time of the Dred Scott decision, five of the justices were Southern Democrats; with them voted two Northern Democrats; and only one Republican and one Northern Whig voiced dissenting opinions.

The first of the cases on the foreign slave trade to come before the court was that of the Antelope, brought up for adjudication in 1825. The facts were these: a Venezuelan privateer, the Arranganta, secretly fitted out in Baltimore, sailed for Africa to prey upon slavers and capture their cargo for its own profit. Among its victims were a Spanish ship, and an American vessel, the Antelope. Subsequently— for reasons not vital to this discussion —all the Negroes were transferred to the hold of the Antelope, which then hovered about the southern coast of the United States, hoping to turn a deal in slaves.

The Antelope, however, was captured by a United States revenue cutter and taken to the port of Savannah. About 280 Negroes were found on board. The federal government asserted that the Negroes had been brought to the country in violation of the law, and were free. The Circuit Court of Georgia liberated those Negroes originally captured from the American vessel off the African Coast, but awarded others to the Spanish claimants. The government then appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

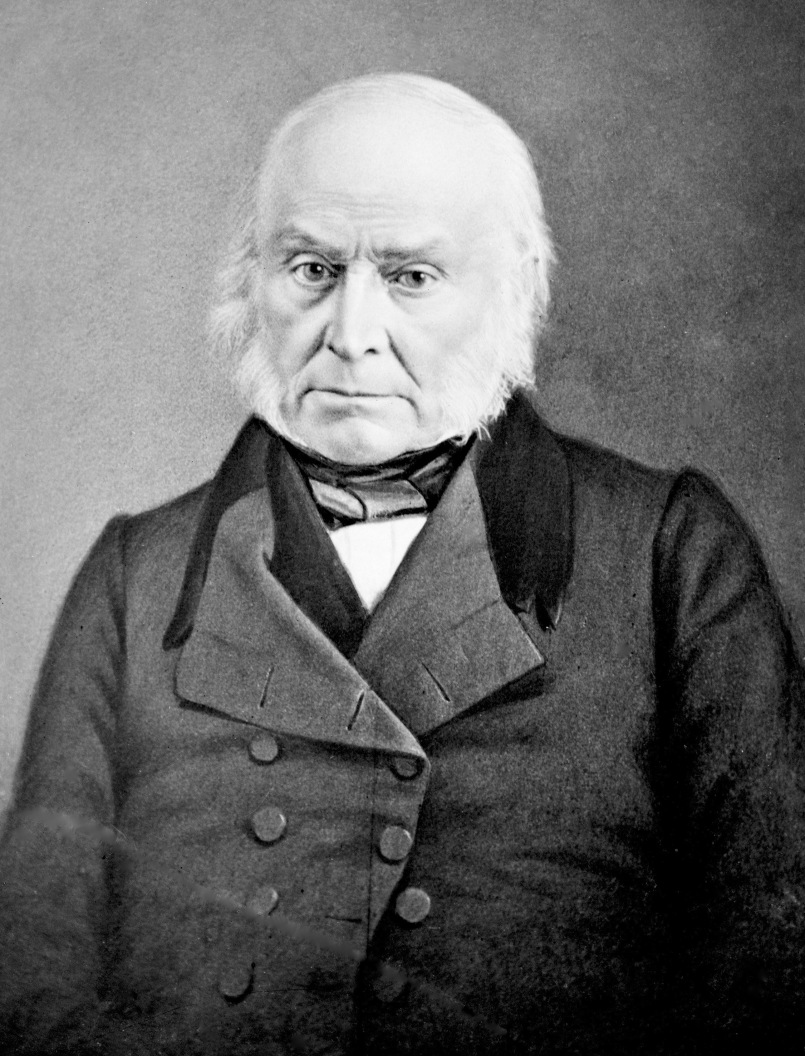

An Act of Congress of 1807 had declared forfeit “any ship or vessel found hovering near the coast of the United States, having on board any Negro, mulatto, or person of color, for the purpose of selling them as slaves”. Ex-President John Quincy Adams, arguing the case for the government in the highest court, pointed out that this act made no distinction as to the national character of the ship. The court, however, chose to base itself rather on a supplementary federal statute of 1820, making the slave trade piracy when carried on by citizens of the United States. It was this last phrase which the court emphasized in its opinion, pronounced by Chief Justice Marshall, restoring to the Spanish Consul the Negroes whom he claimed on behalf of Spanish citizens. It should be noted, in this connection, that Spain had also prohibited foreign slave trade.

The essence of the decision was, first, that the institution of slavery was legal, and, second, that the nations of the world had not outlawed the slave trade, nor declared it to be piracy, and that it was therefore justified.

“Slavery,” said Marshall, “has its origin in force; but as the world was agreed that it is a legitimate result of force, the state of things thus produced by general consent cannot be pronounced unlawful.”

The Negroes, he explained, had been legally captured in “war’’—a “war” of the white invaders against the natives of Africa.

“International law,” the opinion stated, “‘is decidedly in favor of the legality of the slave trade.”

That trade might, in consequence, be lawfully carried on by those nations which had not prohibited it; it was not piracy; and the right of visitation and search—by which alone the slave trade could be suppressed—did not exist in time of peace. Marshall took occasion to express regret that in this litigation “the sacred rights of liberty and of property come in conflict with each other’; the conflict was resolved, nevertheless, in favor of property.

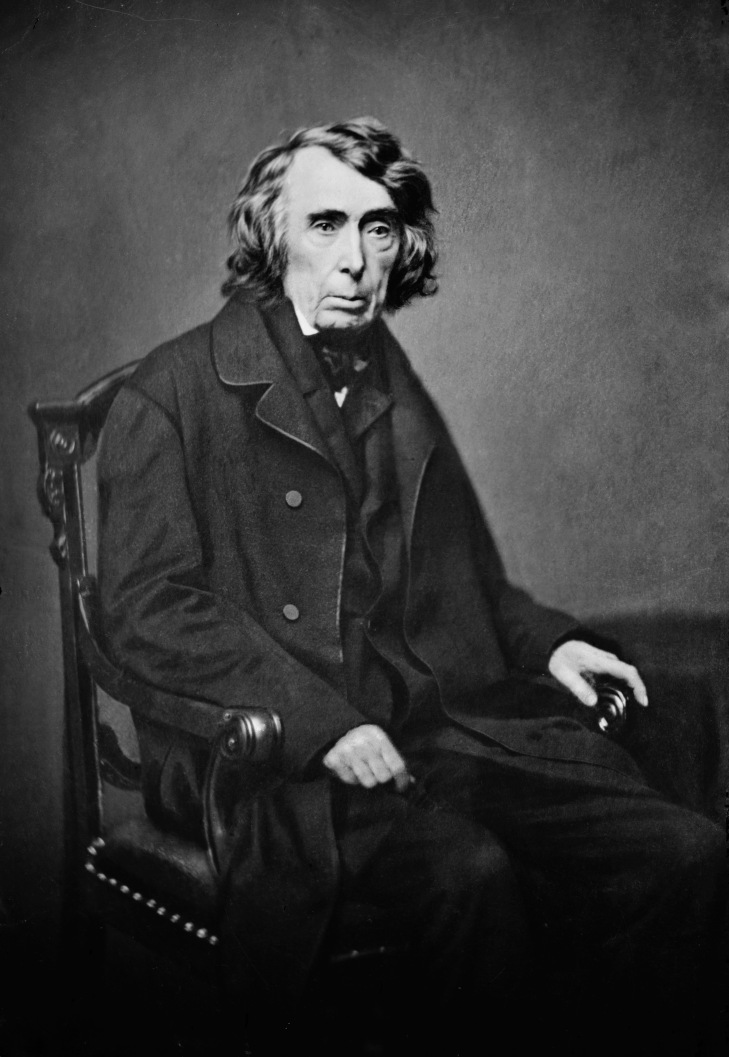

Two years later, the highest court handed down a decision in the case of John Gooding, a notorious slave-trader indicted in Baltimore. His attorney, Roger B. Taney, later Chief Justice, carried an appeal to the Supreme Court. Taney made no attempt to deny his client’s guilt; he based his plea instead on alleged defects in the indictment. By means of hair-splitting legal technicalities, the court found judgment for Gooding.

Within little more than a decade, however, the Supreme Court delivered two further decisions touching the African slave trade; one (the United States vs. Isaac Morris, 1840) dealt severely with a citizen of the United States who served on board a slaver; the other freed a group of Negroes who, seized in Africa and transported to Cuba, rose in revolt and took possession of the ship.

At first glance, these decisions might be thought to indicate a change of heart by the Supreme Court. But there was, in actual fact, no betrayal of the interests of the slave-owners. As the years passed, the border states, their soil exhausted by slave cultivation, turned more and more to systematic breeding of slaves for market; to them, the importation of African Negroes represented unwelcome competition. To hold the loyalty of the border states, the slavocracy agreed to forego the foreign slave trade. Further, it was to the interests of the wealthiest and most powerful of the slave owners to prevent the glutting of the market and the consequent fall in the value of their property. It was not they, but rather the middle and lower strata among the slave owners, who voiced the demand for cheap slaves. For these reasons, even the Constitution of the Confederacy, adopted in 1861, continued the prohibition of the African slave trade.

An insurrection of Negroes aboard a Spanish slaver in 1839 resulted in a long judicial controversy, in the course of which mass pressure on a widely organized scale was brought to bear on the highest court.

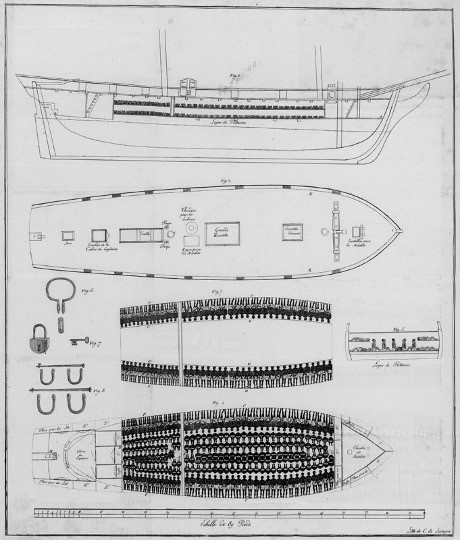

In violation of the laws of Spain, the schooner Amistad, with about sixty Negroes and two white passengers, left Havana for Puerto Principe, another Cuban port. The Negroes spoke no Spanish, and were obviously recent captives from Africa; but it was the custom of the Cuban authorities not to inquire too closely into a profitable business. The story of the Negroes’ capture and transport was typical of the cruelties of the trade. Seized and manacled on the African coast, they were rammed into the slave ship and, in a space not over four feet high, they sat crouched, day and night, chained in couples by wrists and legs. An unknown number of men, women, and children died on the passage. In Havana, the captives were kept in their irons, starved, and regularly beaten.

Four nights out from Havana, the Negroes rose, killed the captain and three of the crew, and took possession of the vessel. The two white passengers were spared to navigate. They steered for Africa by day, but each night they turned the ship about. For sixty-three days the Amistad cruised about the western Atlantic waters, finally putting in at the Long Island coast. The appearance of the vessel aroused suspicion, and a United States steamer and several revenue cutters were sent to investigate.

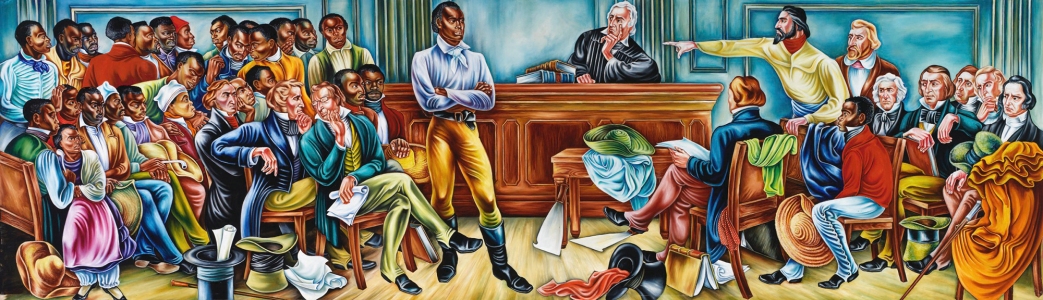

Fifty-four Negroes—three of them young girls—were taken alive from the Amistad. The two white passengers filed claims to them as slaves; the case went in time before the Supreme Court, and the Negroes were kept in jail pending the outcome.

Under the leadership of the Abolitionists, a mass defense movement was organized. Appeals in the anti-slavery press brought funds to cover legal expenses and to provide prison comforts. The protests which poured in upon the Supreme Court caused a government committee to report in indignation:

“A lawless combination, insisting that these blacks were guilty of no offense, resisted their being punished. Zealots, with the help of the press, resisted the cause of justice, and resolved to free the Negro malefactors. Moral force and intimidation were put in operation to awe the courts. The fanatical denunciation of Negro slavery created these blacks heroes and martyrs.”

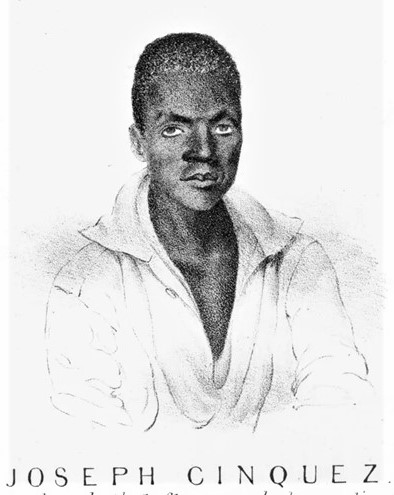

Basing itself on Spain’s prohibition of African slave trade, the Supreme Court in 1841 decided that the Negroes had been seized contrary to law, and were entitled to their freedom. Mass meetings greeted the insurrectionists upon their release from jail, and Cinque, leader of the uprising, addressed cheering New England crowds in his native tongue.

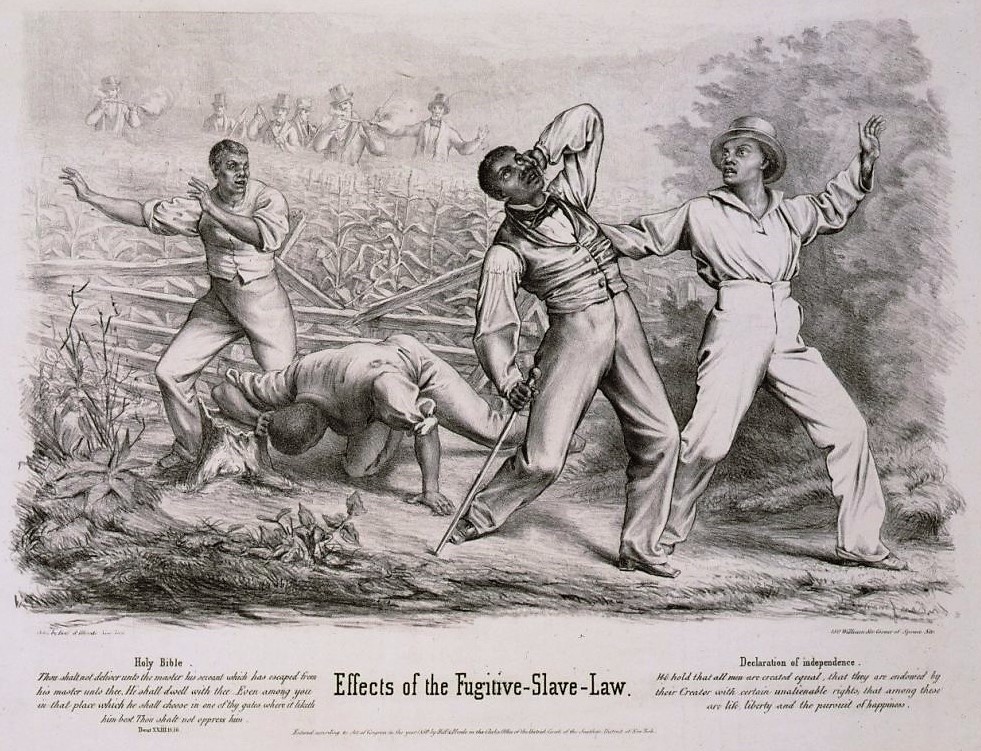

In four decisions the highest court upheld the constitutionality of the two federal fugitive slave acts, which made aid to runaways a crime. The first of these cases was that of Prigg vs. Pennsylvania. The immediate question at issue was the legality of Pennsylvania’s “personal liberty” law, one of the many statutes passed in Northern states. upon the insistence of the people, to hinder the operation of the fugitive slave acts. The Pennsylvania law detailed the procedure whereby a run- away could be recovered, and made punishable recapture in any other manner.

In 1837, the slave-catcher Edward Prigg came to Pennsylvania to seize Margaret Morgan, who had been a slave in Maryland. Finding the procedure prescribed too slow, Prigg kidnapped the fugitive. Arrested and convicted of violation of the Pennsylvania statute, he appealed to the United States Supreme Court, contending that the “personal liberty” law was unconstitutional and void, since it had the effect of nullifying the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.

Pronouncing the opinion of the court in 1842, Justice Story pointed out the contradictions between the state and federal regulations on the recapture of fugitives. The Act of 1793 authorized arrest without a warrant; the Pennsylvania law required one. The federal act admitted the oath of the owner or his agent as proof of claim; the Pennsylvania law excluded the testimony of both on this point, and required the testimony of disinterested witnesses.

The Pennsylvania law, said Story, was therefore unconstitutional as was “… any state law or regulation, which interrupts, limits, delays, or postpones the right of the owner to the immediate possession of the slave, and the immediate command of his service and labor. We hold the law [of 1793— E.L.] to be clearly constitutional.”

Thus the highest court upheld the constitutionality of an act which denied the rights of trial by jury and of habeas corpus. One of the immediate effects of the Prigg decision was to nullify an act of New York State, granting jury trials to alleged fugitives.

Still another portion of the court’s opinion reversed one of the fundamental principles of Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence: it declared that “in a state where slavery is allowed, every colored person is presumed to be a slave”. This removed the burden of proof from the slave-catcher, and threw it upon the defendant, to show that he was free.

But there was a joker in the decision. The constitutionality of state laws passed in aid of the claimant of runaways was not involved in this case, but the court, anxious to place all matters concerning fugitives in the hands of the pro-slavery national government, gratuitously expressed the opinion that Congress alone had power to legislate on recapture, and that state laws designed either to hinder or to assist the federal statute were alike un- constitutional. Taking advantage of this portion of the opinion—which the court was to repudiate some years later —the Northern states continued to pass “personal liberty” laws, forbidding the use of state jails for the imprisonment of fugitives, and prohibiting state officials from assisting in the execution of the federal statutes.

The constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 was again brought into question in the case of Jones vs. Van Zandt, decided by the court in 1847. The John Van Zandt of the controversy was an Abolitionist and keeper of a “station” on the “underground railroad”. Returning to his farm from a trip to Cincinnati in 1842, Van Zandt transported in his wagon nine Kentucky fugitives. He was overtaken on the road by a party of slave-catchers, one of whom, peering into the covered wagon, asked, “Van Zandt, is that you? Have you a load of runaways?” To this Van Zandt replied: “They are by nature as free as you or I.”

The slave-catchers succeeded in re- taking all but one of the Negroes. Tried and convicted in the United States District Court, Van Zandt declared himself ready to repeat the “offense” at any time. He appealed to the Supreme Court, alleging the unconstitutionality of the law of 1793. The court upheld the conviction, again affirming the legality of the 1793 Act, and declaring: “All of its provisions have been found necessary to protect private rights.”

The private rights to which the court referred were, of course, the rights of the slave-owners.

The federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, with its more stringent regulations, superseded the law of 1793 and, like its predecessor, was twice tested and upheld by the Supreme Court. The first case was that of Moore vs. Illinois, decided in 1852. Richard Eells, of Quincy, Illinois, had sheltered a Negro runaway, and had been tried and convicted of violation of a state law, which punished the harboring of fugitive slaves. The Supreme Court, to which the verdict was appealed, now found itself in difficulties because of its gratuitous expression of opinion in the Prigg case, that state laws purporting to assist recapture were as unconstitutional as those obviously designed to hinder it. To this portion of the Prigg verdict Eells now referred, to up- hold his contention that the Illinois statute was unconstitutional. Embarrassed, the court said that this question had never properly come before it; that “this court has not decided that state legislation in aid of the claimant, is void”.

Justice Grier delivered the opinion of the court:

“A state,” he said, “has a right to make it a penal offense to introduce paupers, criminals, or fugitive slaves within her borders. Some of the states have found it necessary to protect themselves against the influx either of liberated or fugitive slaves, and to repel from their soil a population likely to become burdensome and injurious either as paupers or criminals. If a state should thus indirectly benefit the master of a fugitive, no one has a right to complain that it has fulfilled a duty assigned or imposed by its compact as a member of the Union.”

Particularly noteworthy in this decision is its reversal of an opinion in the Prigg case; its justification of state laws barring free Negroes; and its lumping of “paupers, criminals, or fugitive slaves”.

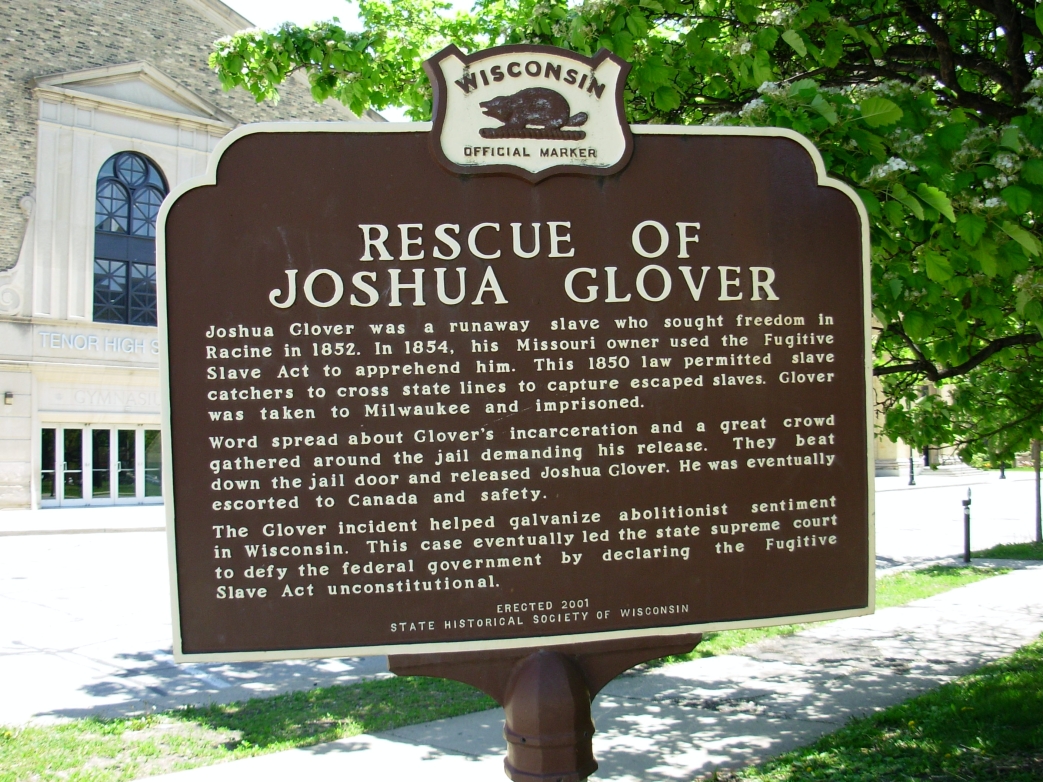

A most important judicial struggle centering around the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was the case of Ableman vs. Booth. In the course of it, the Wisconsin Supreme Court defied the United States Supreme Court and re- fused to carry out its mandates. The case was decided by the highest court in 1858; the facts were, briefly, these:

The runaway slave Joshua Glover was seized at Racine, Wisconsin, in 1854, and taken in chains to prison in Milwaukee. Summoned by the courthouse bell, the people of Racine gathered in mass meeting, and elected a committee of 100 to arrange for Glover’s defense and a jury trial. The committee took boat for Milwaukee, where they found men already riding horseback through the streets, crying: “All free citizens, who are opposed to being made slaves or slave-catchers, turn out to a meeting in the Court House Square at two o’clock.”

Five thousand persons gathered and passed resolutions against the recapture of fugitives. “We, as citizens of Wisconsin,” they stated, “do hereby declare the slave-catching law of 1850 disgraceful and repealed.” Then, learning that a writ of habeas corpus had been disregarded by Glover’s captors, they marched upon the jail, stormed it, and released the Negro, who succeeded in reaching Canada.

Accused of being the instigator of this rescue, Sherman M. Booth, editor of an Abolition paper in Milwaukee, was arrested, charged with violation of the Fugitive Slave Law. He was convicted in United States District Court. His bearing at the trial made him a hero of the anti-slavery forces. He regretted, he said, that he had not taken more active part in the affair.

“So far from having to reproach myself with what I have done,” Booth declared, “I ought, perhaps, to blame myself for not having done more. Instead of keeping, as I have done, strictly to the letter of the law, perhaps I ought to have braved the penalty of those who broke open the jail, and set an example of resistance to this Fugitive Slave Law by aiding in the forcible rescue of Glover.”

Denouncing the federal law as “a stupendous fraud, as wicked as stupendous, and a nullity before God and man”, Booth stated:

“I am frank to say—and the prosecution may make the most of it—that I sympathize with the rescuers of Glover and rejoice at his escape. I rejoice that, in the first attempt of the slave-hunters to convert our jail into a slave-pen and our citizens into slave-catchers, they have signally failed, and that it has been decided by the spontaneous uprising and the sovereign voice of the people that no human being can be dragged into bondage from Milwaukee.”

Upon application to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, Booth was granted a writ of habeas corpus and freed from jail. That court declared the federal Fugitive Slave law unconstitutional. The verdict of Wisconsin was appealed to the United States Supreme Court. Counsel for the defense argued the unconstitutionality of the law of 1850, pointing out that it refused Negroes claimed as fugitives the right to trial by jury, thus depriving them of liberty without due process of law. The contention was denied by the court, which, in a decision rendered by Chief Justice Taney, ordered the Wisconsin Court to reverse itself and remand Booth to jail.

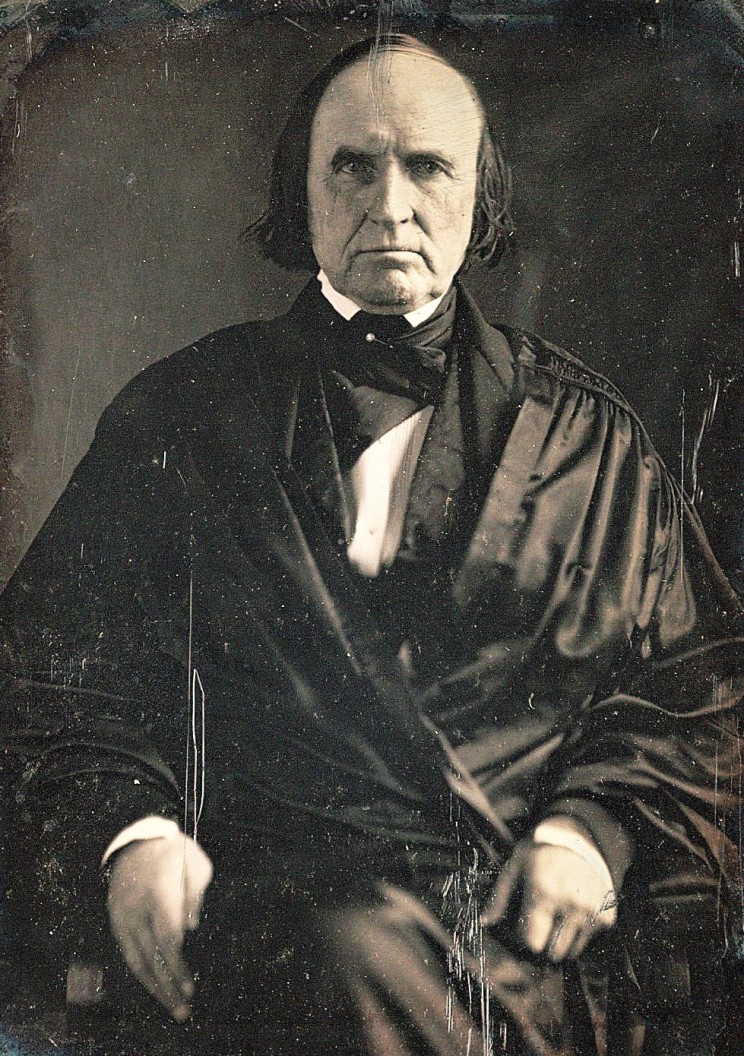

This instruction the Supreme Court of Wisconsin refused to carry out, and Booth remained for several years a free man. Finally, however, the composition of the Wisconsin court changed, and when in 1860 another order arrived for Booth’s arrest, he was denied habeas corpus. He was rescued from jail, and two further attempts at his seizure were forcibly prevented, in one case by an armed guard of sixty-two citizens. At last the authorities succeeded in holding him, and he remained in prison until, just before the Civil War, he was pardoned by President Buchanan.

At every stage of the controversy the people made themselves heard. The excitement spread far beyond the boundaries of Wisconsin. The argument of Booth’s counsel, printed in pamphlet form, was distributed in thousands of copies. Mass meetings were called in many states to thank the Glover rescuers; at these meetings, a fund was made up for the defense. When Booth was eventually sent to jail, the church bells and cannon of Milwaukee summoned the citizens to the railway station to see him off.

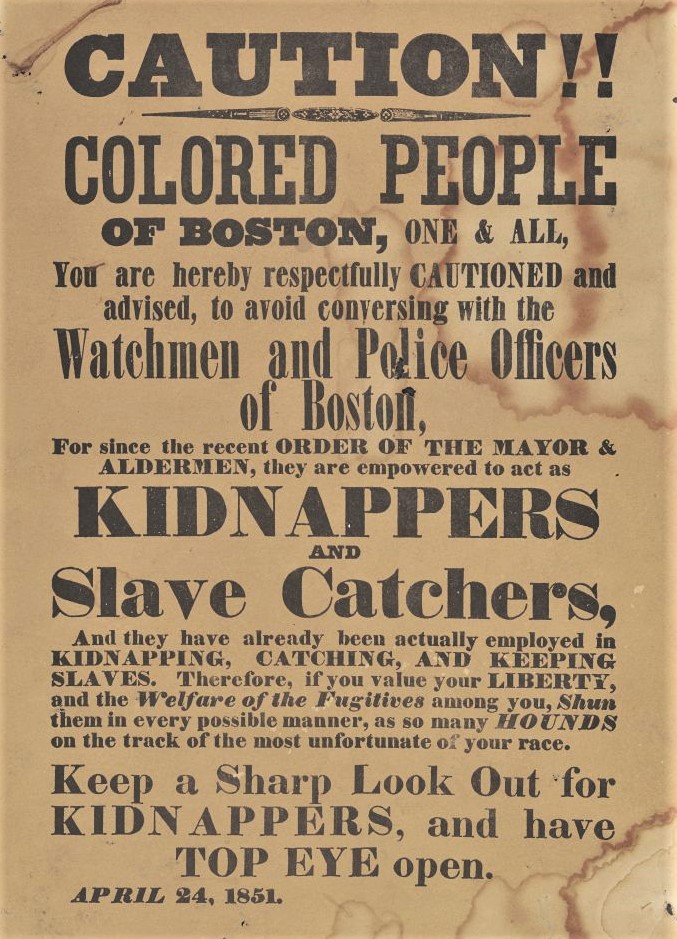

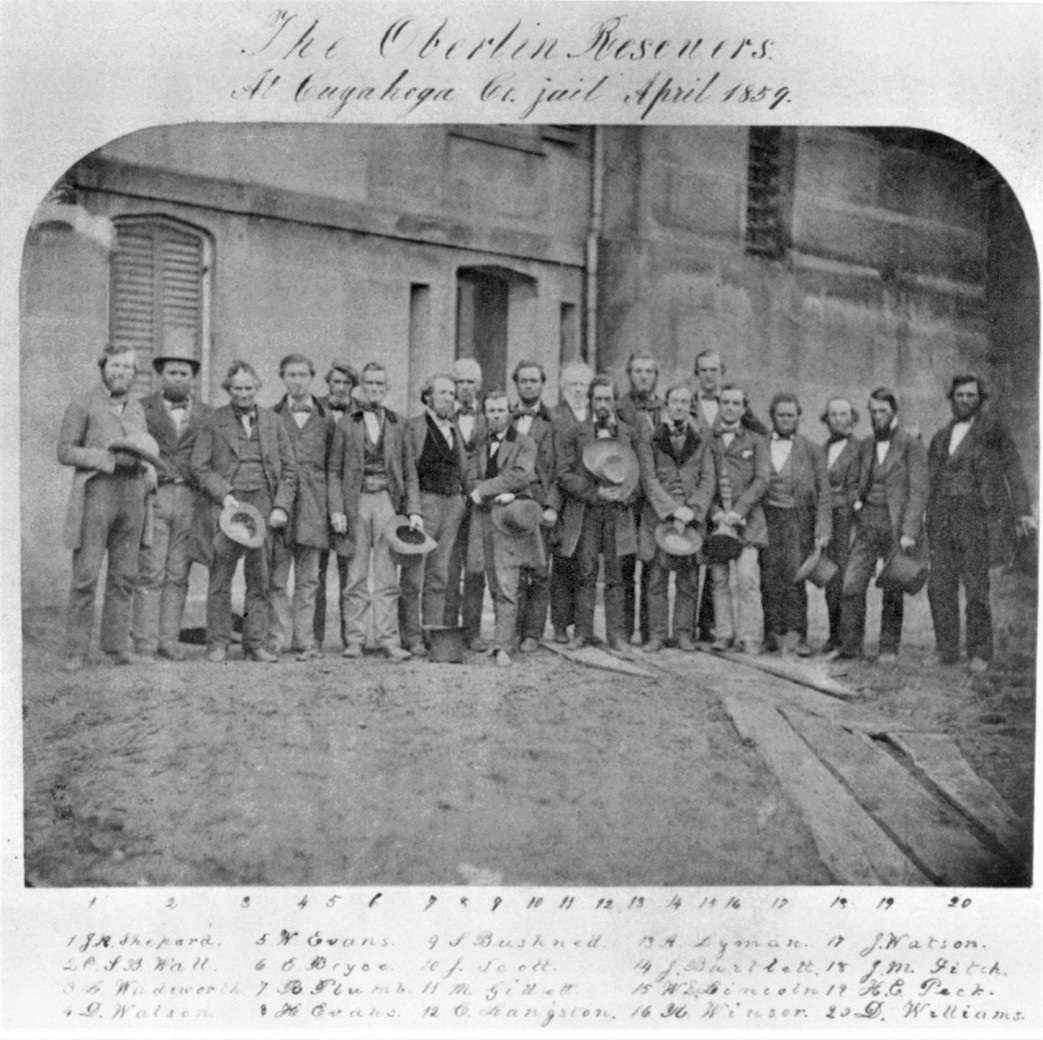

The repeated decisions of the Supreme Court upholding the fugitive slave laws only steeled the anti-slavery forces. In 1854 the federal government was forced to spend $40,000 for infantry, cavalry, artillery, and marines to return Anthony Burns from Boston to slavery in Virginia. Almost every Northern state had its “Booth” case, following rescues or attempted rescues of Negro runaways who had fallen into the hands of the officials. In Oberlin, Ohio, to mention but one instance, a professor and several college students were among those tried after a Negro had been taken from his captors and sent on to Canada. The defense of victims of the fugitive slave laws foreshadowed in many respects the defense of class-war prisoners today: the courts became forums for the expression of anti-slavery sentiments; the stories of the trials were printed and widely distributed; funds were collected by popular appeal; and mass gatherings of Negroes and whites sent messages of solidarity to the defendants and denounced the fugitive slave laws and the Supreme Court’s subserviency to the slave power.

During these years, “underground railroad” developed into a great network of secret travel, systematically organized, and involving to greater or less degree hundreds of thousands of persons; over this “railroad” an average of a thousand slaves a year escaped to free soil. Persecution of slave-catchers became a science and an art; two who arrived in Boston in 1850, to seize the daring fugitives William and Ellen Craft, complained that “they could not step into the street but that they were surrounded by jeering men”. In the Liberator appeared this significant sentence:

“The warrants for the arrest of William and Ellen Craft have been issued; no officer has yet been found bold enough to serve them.”

In three decisions on the legal status of slaves, the Supreme Court tightened the bonds of slavery, declaring that even residence on free soil with consent of the owner did not strike off the chains. The first of these decisions was made in the case of the ship Garonne, in 1837. A resident of New Orleans had gone to France, taking with her a Negro girl as personal servant. On their return, the Negro was continued in slavery. The ship in which the girl arrived—the Garonne—was held for breach of the Act of Congress of 1818. That Act provided: “It shall not be lawful to import or bring, in any manner whatsoever, into the United States, any Negro, mulatto, or person of color,” with intent to hold “such person as a slave.” The Supreme Court, anxious to cause the slaveholders no inconvenience, held that the provisions of the act did not apply to slaves taken out of the country and brought back. A related question—whether slaves sent into a free state for temporary work were thereby emancipated—was decided by the highest court in 1850, in the case of Strader vs. Graham. Here again, as always, the court gave slavery the benefit of the doubt.

Christopher Graham was the owner of two slaves who had escaped from Kentucky into Canada. Finding that they had been transported in the steamboat Pike, Graham sued Jacob Strader, one of the boat’s owners. Strader’s defense was that the Negroes were already free when they embarked; they had previously, with Graham’s consent, gone to Ohio to perform in a band. Defense counsel pointed out that if residence in a free state, with consent of the owner, did not free the slave, there would be nothing to prevent citizens of Ohio, for example, from hiring slaves from Kentucky and thus in effect nullifying Ohio’s emancipation act.

The Supreme Court decided that it had no jurisdiction in the case—that is, that the slave states alone could determine the status of Negroes who had left their boundaries and returned.

By the middle of the century, the Supreme Court had rooted slavery firmly in the law; it had again and again reiterated the legality of the institution, thus pronouncing upon it a judicial blessing; it had locked every door and fastened every window of the slave’s prison house. One task was left: to provide for slavery’s spread across the continent. This was the most important assignment that the court was called upon to carry out for, to American slavery, the opportunity for expansion was the very breath of life. Congress had begun the task in 1854 with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed that pro- vision of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that declared territory north of the line of 36°30’ to be forever free. The Kansas-Nebraska Act established “popular sovereignty”; ostensibly, the right of the people of a new state to determine for themselves the question of slavery or freedom; actually, the right of the slave-owners to take their human chattels into all portions of the unsettled West. The legality of the Kansas Act was, however, constantly called into question. Further, it failed to solve an important problem: when did the right of the settlers to accept or reject slavery begin? While the land was still in territorial status? Or only when it acquired statehood? This was more than a legal quibble, for that system of labor which first acquired a foothold in the territories would almost inevitably drive out its rival.

To assure the right of the slavocracy to extend its domain from ocean to ocean, the Supreme Court took advantage of what would ordinarily have been a minor tangle at law, and pronounced the Dred Scott decision.

The facts in the case were simple. A Negro slave, Dred Scott, brought suit against the widow of his former master in the State Circuit Court of St. Louis, alleging that his sojourn in territory north of the Missouri Compromise line, in his master’s service, had effected his liberation according to the terms of the statute.

It was the contention of Dred Scott’s master that a Negro was not a citizen of the United States, and could not sue in the federal courts. He asked, therefore, that the case be dismissed. The Supreme Court agreed that a Negro had no right to sue. That being so, it was not necessary to enter into questions raised in the litigation. But the justices were not willing to terminate the controversy so simply. They felt that the time had come to deal Abolitionism a judicial blow.

The leaders of the slavocracy were awake to the opportunities offered by the Dred Scott case. On all occasions, they impressed upon the justices their chance to settle the question of slavery extension. It was Alexander H. Stephens, later Vice President of the Confederacy, who organized this pressure. “I have been urging all the influence I could bring to bear upon the court,” he wrote to a friend, “to get them to postpone no longer the case in the Missouri restriction.”

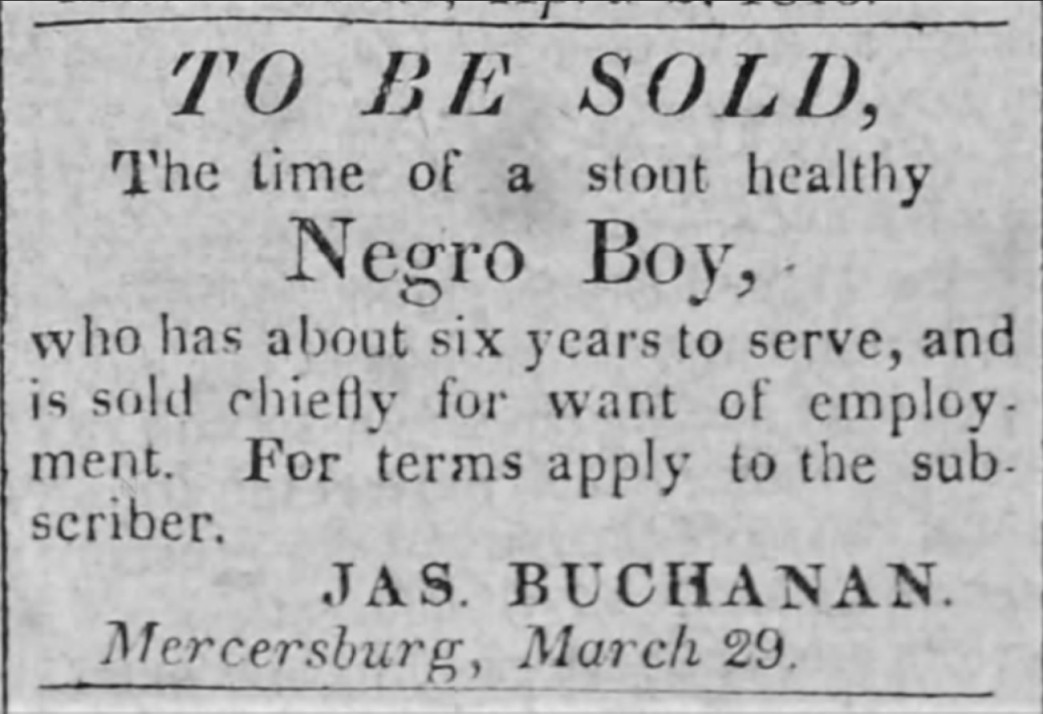

Confidential letters which have since come to light show that the Southern members of the court were in constant communication with the incoming President on the progress of the case; that the more aggressive of the pro-slavery justices used Buchanan to whip up their colleagues; and that Buchanan’s pretense, in his inaugural address, that he was ignorant of the nature of the forthcoming decision, was a lie uttered in the first hour of his administration.

Less than a month before the inaugural, Justice Catron of the Supreme Court wrote to Buchanan:

“The Dred Scott case has been before the Judge [Justice Wayne—E.L.] several times since last Saturday, and I think you may safely say in your Inaugural ‘that the question involving the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise line is presented to the appropriate tribunal to decide; to wit, the Supreme Court of the United States. It is due to its high and independent character to suppose that it will settle a controversy which has so long and so seriously agitated the country.

“Will you drop Grier a line, saying how necessary it is, and how good the opportunity is, to settle the agitation by an affirmative decision of the Supreme Court, one way or the other? He ought not to occupy so doubtful a ground on the outside issue.”

Buchanan’s letter to Grier has not been discovered, but it is evident that there was one, for a few days later Grier wrote to the President-elect:

“Your letter came to hand this morning. I have taken the liberty to show it in confidence to our mutual friends Judge Wayne and the Chief Justice. We fully appreciate and concur in your views as to the desirableness at this time of having an expression of opinion of the court on this troublesome question. With their concurrence, I will give you in confidence the history of the case before us, with the prob able result. There will be six if not seven who will decide the Compromise of 1820 to be of non-effect.”

There were two major questions which the Court undertook to decide. First, was a free Negro a citizen? Second, was that portion of the Missouri Compromise Act which prohibited slavery north of 36° 30’ constitutional?

It was the intention of the framers of the Constitution, declared Chief Justice Taney, to set up in the United States a government of white men. They did not look upon Negroes as citizens. The Negroes had, in fact, been regarded at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, as “beings of an inferior order; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect”. Therefore, Negroes and the descendants of Negroes could never enjoy citizenship. Laws in effect in the colonies when the Revolution began, showed that “a perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery”. The phrase used in the Declaration of Independence, that “all men are created equal”, did not include Negroes, free or slave.

Politically, the most significant part of the decision was that which voided the Missouri Compromise line, and affirmed the right of slave-owners to take their property into any territory of the United States. To rule, as had the Missouri Compromise, that slave- owners might not bring their slaves into the northern portion of the Louisiana purchase, was to deprive citizens of their property without due process of law. The Court again declared the constitutionality of slavery: the Constitution made no distinction between slaves and other property, and no legislative, executive, or judicial authority of the United States could legally make such a distinction.

In a dissenting opinion which the anti-slavery forces printed and spread broadcast throughout the country, Justice Curtis showed that at the time the Articles of Confederation were ratified, free Negroes in no less than five states, including North Carolina, were not merely citizens, but were even included in the electorate. He recalled eight instances in which Congress had in fact prohibited slavery in the territories, in Acts which were signed by all the Presidents from Washington to John Quincy Adams.

Justice McLean, also dissenting, pointed out that in the Prigg case, the Court had decided that “slavery is limited to the range of the laws under which it is sanctioned”. Justice Story had in that case declared for the Court, that “the state of slavery is deemed to be a mere municipal regulation”. McLean stressed the inconsistency: in the former decision, the Court had held slavery to be local, not national; it now held slavery to be national, and not merely local. He referred also to the well-known fact that, in the early days of the Republic, slavery was believed to be a temporary institution, already on the path to extinction.

The Dred Scott decision aroused mass resistance to the entire judicial machinery. A few of many possible quotations from the press will show the temper of the people:

The New York Independent “If there be not aroused a spirit of resistance and indignation, which shall wipe out this decision and all its results, as the lightning wipes out the object it falls upon, then indeed are the days of our Republic numbered.”

The New York Tribune: “We propose to revolutionize the revolution. We intend to strike directly at the usurping power. That power is slavery.”

James S. Pike, the Tribune’s special correspondent in Washington, wrote that the opinion of the Court deserved “no more respect than any pro-slavery stump speech made during the late presidential canvas”. Then, referring to the fact that the decision was, for the most part, superfluous, legally unnecessary, he went on:

“They [the judges—E.L.] were in hot haste to enter the service of slavery. They could not wait to be called. They hurried upon infamy.”

The mass anger and resentment were reflected in state and national legislative halls. William H. Seward of New York attacked the decision in the United States Senate. The New York legislature adopted a resolution declaring that the Supreme Court had “impaired the confidence and respect of the people”. Simultaneously, it passed an act to the effect that every Negro entering the state should be free. The legislature of Maine resolved that the extra-judicial portion of the Dred Scott decision was “not binding, in law or in conscience, upon the government or citizens”.

At the time the Dred Scott opinion was rendered, a constantly increasing number of people, aroused to the necessity of barring slaves from the new territories, were sundering old political ties and perfecting the Republican Party as their instrument in the struggle. But if slavery could not be kept out of the territories, the new party was striving to accomplish an illegal purpose. Far from shattering the Republican ranks, however, the decision helped to weld the political union of all progressive groups and classes, against the overwhelming menace of the slavocracy.

Abraham Lincoln, now rapidly coming to the fore as the leading figure in the fight against the extension of slavery, publicly charged collusion and conspiracy between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the government, on behalf of the slave-owners. Further, he denied the right of the Supreme Court to invalidate laws of Congress.

“If the policy of the government upon vital question affecting the whole people,” he stated, “is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

Lincoln quoted with approval a letter written by Jefferson in 1820:

“You seem to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions— a very dangerous doctrine indeed.”

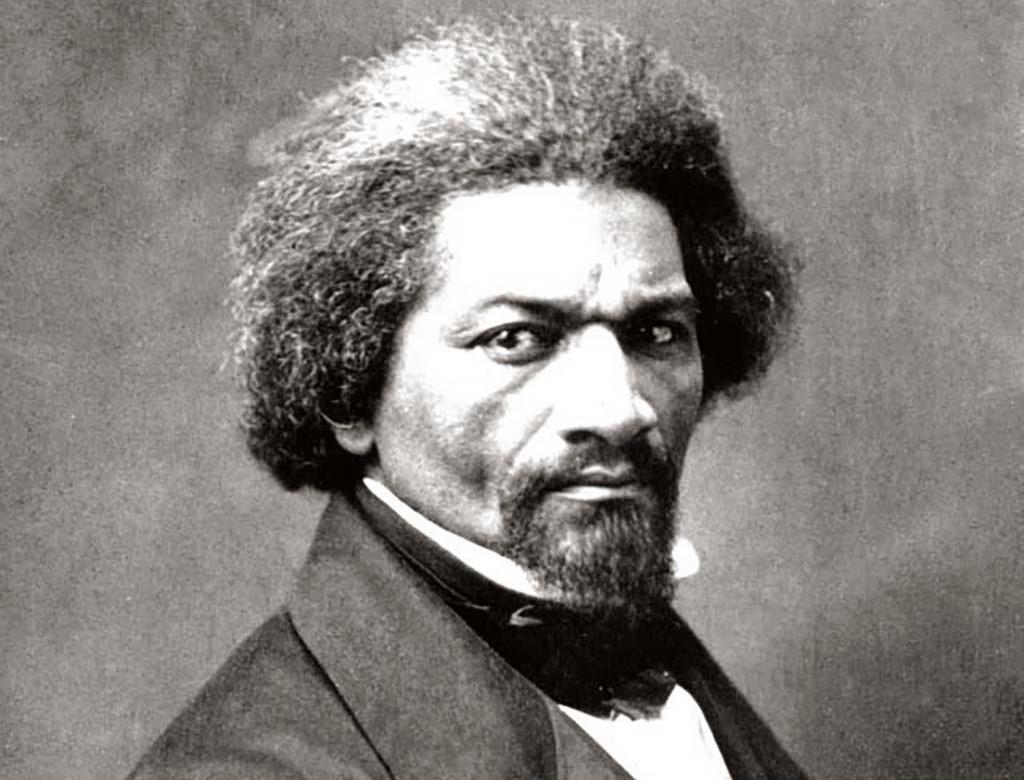

It was Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave, the great orator of Abolition, who most clearly proclaimed the feelings and intentions of the masses:

“We can appeal from this hell-black judgement of the Supreme Court, to the court of common sense and humanity. You may close the ears of your Supreme Court to the black man’s cry for justice, but you cannot, thank God, close against him the ear of a sympathizing world.”

There were a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘The Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v16n04-apr-1937-The-Communist.pdf