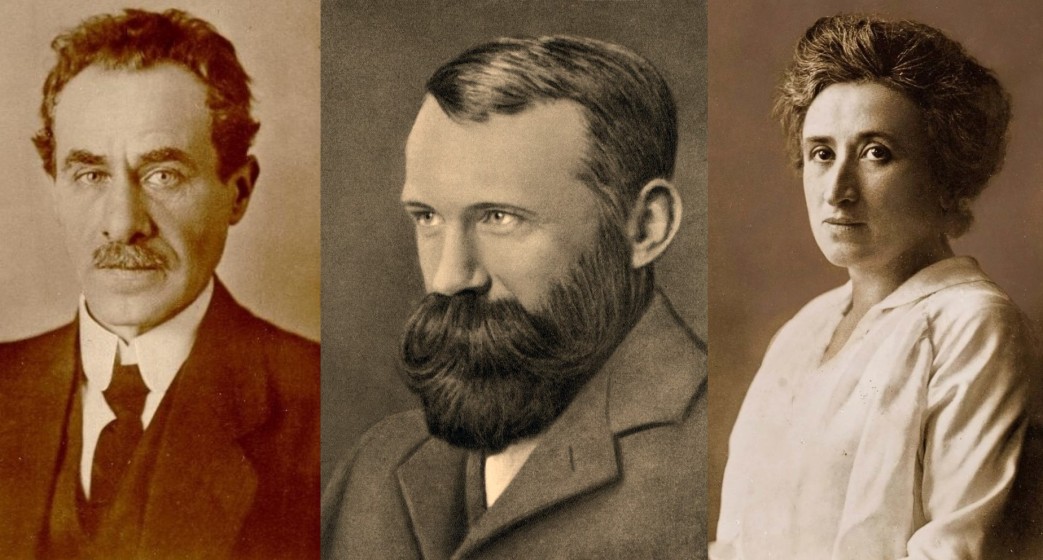

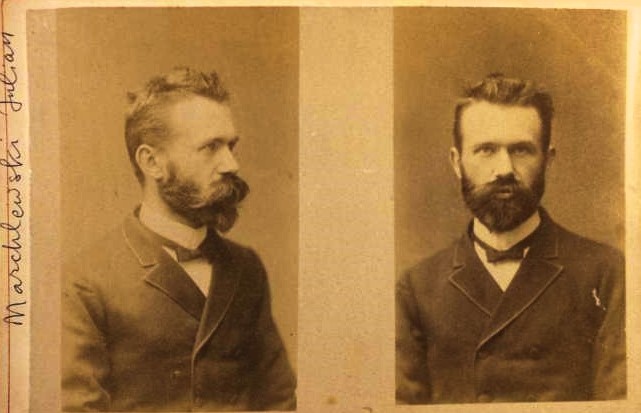

Julian Marchlewski, among the closest and oldest comrade to Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, wrote this appreciation shortly after their murders. The three formed a political bond during their 1892 exile in Zurich, where they founded the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland together. Each other’s stalwarts, their ambitious work, political development, comradeship, and personal intimacies ended only in their deaths after twenty-five years of continuous revolutionary activity together. One of our movement’s great political collaborations and partnerships. While Rosa’s greater accomplishments and importance in the mass movement were readily acceded to by Jogiches and Karsky, all were indefatigable and brought complimentary skills to their common fights. Each bravely played a heroic role in the freedom struggle. While Karsky is due his own lengthy appreciation, there is not a better comrade to pay tribute to his illustrious friends. Transcribed for the first time, this essay is an important contribution to the history of these three exemplary revolutionaries and human beings.

‘In Memory of Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogihes from Personal Reminiscences’ by Julian Marchlewski (Karski) from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 3. July 1, 1919.

In devoting this article the memory of comrades Luxemburg and Jogihes, I combine their names not only because they shared the same fate–a martyr’s death at the hands of the brutal henchmen of the German social traitors–but also because these two eminent promoters of the cause wore closely bound in life by a thirty years’ friendship and joint labour in the service of the same ideas.

Rosa Luxemburg was born in 1870, in the small Polish town of Zamost, in once wealthy, but later impoverished, Jewish family. In the beginning of the eighties the family moved to Waraw and Rosa entered a girls school. She preserved the brightest memories of her family life. Her mother was a cultured woman. She loved to read with her children the creations of Polish and German poets, and the impressionable girl grew passionately fond of poetry, and under the influence of these works herself began to write verse. She was specially devoted to Mickiewicz and in her later literary work you will not often find a Polish article wherein does not occur some quotation from one or another of his poems. The family frequently suffered from actual want and often even the bedding was pledged for a few roubles; but even that did not evoke, —as such things too often do, bitterness or depression of spirit. I remember Rosa relating how once she lit the lamp with scrap of paper, which afterward proved to have been the last money in the house which her father had procured with great difficulty. The old man not only did not punish his daughter, but, after recovering from the first shock, comforted her with jests about the expensive match. This sunny moral atmosphere undoubtedly aided the development of the intellectual gifts of freedom’s future champion. Those gifts were remarkable and showed already at school. Rosa graduated from the gymnasium with honours, and that she did not receive the golden medal was due only to the fact that the governor was suspicious of her “political honesty.”

These suspicions proved welt founded: as a schoolgirl she already belonged to a circle of youthful socialists, where pamphlets were read, published by the party calling itself “The Proletariats” and dreamed of going to work among the labouring class. But the police were not asleep, and, as early as 1888, the 18-year-old conspirators had to seek refuge abroad. Her flight was arranged by Comrade Caspŕjak, at that time the cleverest conspirator of the party, who subsequently ended his life on the gallows.

Luxemburg found herself in Zurich. There she lived in the family of a German emigrant, a social-democratic.

journalist, Dr. Karl Lübeck. He was married to a Polish woman, and Rosa felt at home in that family. Lübeck was a very clever man of vast knowledge, but desperately ill, a paralytic. The warmest friendship sprang up between him and the young student; under his dictation she wrote the articles with which he earned his livelihood and talked with him for hours, continuing her studies under his guidance. Comrade Luxemburg in these first years of her studentship undoubtedly owed much to this exceptionable man.

In 1891 Rosa became acquainted with Conrade Jogihes, I possess no information on his earlier youth, neither, so far as I know, do others who worked with him for many years. This is explained by the fact that Jogihes disliked to speak of himself and never confided anybody with his personal affairs. There may possibly be friends who know him more intimately, if so they will tell of his childhood and early youth.

I will relate what I succeeded in finding out: Leo Samuilovitch Jogihes was born in Vilna in 1867, in a very wealthy Jewish family. He commenced early to participate in the revolutionary movement, and in 1888 was arrested by the Vilna police for “active propaganda of anti-government ideas among the workingmen.” He was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment, then was placed under police surveillance. In 1900 he fled abroad, so as to elude military service. Finding himself in Switzerland, he entered into relations with Plekhanoff but soon differed with him and left him. It was a time when very ugly conditions obtained in Russian social democratic circles. The movement was but just beginning in Russia; and Plekhanoff arbitrarily managed the emigration. Whosoever did not settle matters with him personally, fell into dis-grace, and his right to the name of social-democrat was disputed. Comrade Jogihes was not of an accommodating temper and would not submit to such a régime. He was soon joined by other members of the emigration and decided to act independently. The most urgent question then was that concerning revolutionary publishing: both the young emigrants and the labour circles in Russia stood in great need of literature. Jogihes could dispose of considerable means and having collected a group of contributors: (Kritchevsky, Riazenof, Parvus), proceeded to issue the Social-democratic Library. Here his capacity for organization at once asserted itself. He did not write himself, but he proved an ideal editor, almost pedantically accurate; the issues appeared in excellent form and the transport also was well organized.

Simultaneously with his editorial work, Jogihes was engaged in adding to his scientific knowledge. He was remarkably well gifted and quickly found his way into the most complex questions, possessing a splendid memory and a vast amount of reading.

And more: Comrade Grozofsky (which was his pen name then) gave wonderful advice to the party journalists, Once having become interested in some particular question, he was able to prepare a most exact and practical plan for its elaboration; but he had difficulty in writing, though it were but the simplest newspaper article. He was conscious of this and nothing, but absolute necessity could drive him to his pen.

And now, having become acquainted with Rosa Luxemburg, he grew interested in questions of Polish socialism, which agitated her at that time. He studied the Polish language, which he had not known till then, and that so thoroughly, that, later on, when he became editor of Polish periodicals, he most zealously extirpated Russicisms in the articles of Polish comrades. Soon he retired entirely from the Russian movement and devoted all his efforts to the Polish social-democratic cause.

Questions of Polish socialism at that time were exceedingly complicated and interesting. The revolutionary socialist movement, which found expression in the party, named the Proletariat, headed by Ludovic Varinsky and Kunitzky, was passing through a hard crisis in the late eighties. The party concentrated all its forces on terror and was not capable of organizing the labouring masses, who, owing to the rapid growth of capitalism in Poland, instinctively took up a position on purely economic grounds. A “Labour League” was formed in Warsaw, which strove to assume control of the strike movement and, at the same time, carry on a Marxist propaganda, Meanwhile a split took place in the party “The Proletariat” under the influence of the general outbreak of nationalist strivings in Europe, and of the false comprehension of the principle of Labour mass movement, the groups of emigrants who stood at the head of the party became possessed with a tendency of combining socialism with patriotism. Poland, as affirmed by the journalist of this tendency, is economically in advance of Russia, under whose political yoke she lives, and therefore the first object of the Polish proletariat must be the liberation of Poland and the creation of an independent Polish state, with a view to paving the way towards socialism. This resulted in the creation of the Polish Socialist Party.

The “Labour League” combatted this current in Poland, while in Zürich, the centre of the Emigrants, was found a group of young people which strove to oppose it by the general Marxist theory. To this group belonged Comrade Vesselofsky, who was brutally killed by Polish gendarmes; it also contained students, who later left the ranks of the revolutionary fighters, but distinguished themselves in other spheres (among these was one of the most eminent poets of modern Poland, Waslaw Berendt).

It fell to Rosa Luxemburg to create a theoretical basis for the Polish social-democratic movement, and in Comrade Grozofsky she found a capable and self-denying assistant.

The theses, which formed the foundation of the new movement are as follows: Capitalism is developing in enslaved Poland hand in hand with capitalism in Russia, Germany and Austria; the closest bond is necessarily established between the bourgeoisie of the Polish provinces and the bourgeoisie of these dominant states; the class conflict in Poland is becoming sharper and makes a national rising against nation enslavement impossible. The task before the Polish proletariat consists in combatting the capitalistic order conjointly with the Russian, German and Austrian workers; the conducting of this struggle, political and economical, is imperative taking into account the political conditions existing in each of those states,—in view of rich the closest alliance with the socialistic parties in all of them is absolutely necessary; at the same times of course, autonomy must be safeguarded, which makes it possible to satisfy the Polish proletariats’ cultural interests as well. Only and universal revolution that will destroy the capitalist order and the universal sovereignty of capitalism, only such a revolution will bring about the emancipation of all the peoples, including the Polish; so long as the capitalistic order dominate the creation of an independent Polish state is an impossibility. Consequently, the task of the Polish proletariat is to fight, — not for an independent capitalistic Poland, but for the overthrow of all capitalistic states generally.

All this today appears indisputable; but at that time an immense amount of labour was needed to pave the way for these ideas. Rosa Luxemburg showed at once remarkable journalistic talent and brilliant theoretical gifts, and we willingly accepted her as our theoretical guide. Comrade Jogihes was her practical assistant, — although only the closest friends knew of this at the time.

Soon the new movement had to stand its first battle on a wide arena. In the Autumn of 1891 the “Labour League” was destroyed, as nearly all its leaders were arrested. Yet, in spite this, in 1892, the 1st of May demonstration assumed immense proportions and showed that mass action of the workers had become a decisive factor in the social life of Poland.

In 1893 it became possible to renew and extend our revolutionary activity at home. Comrade Vesseloský proved one of the most capable organizers. The new organisation was joined by workers of the “League”, and such as were left of the “Proletariat Party.” We decided to call ourselves the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland. This denomination sounded strange to many, owing to the combination of “socialism” with “kingdom,” but it was chosen with a very definite object: it indicated that we, consistent with our theory, were constructing our organization on special territory, namely in that part of Poland where the proletariat had to carry on the conflict hand a hand with the proletariat of all Russia. It so happened that in the same year, the international Socialist congress s convoked in Zürich. We determined to come forward on this occasion before the proletariat of the whole world. The Warsaw workingmen sent a mandates to me, the foreign groups gave mandates to Rosa Luxemburg and Comrade Varshafsky. The leaders of the “Polish Socialist Party” started a furious campaign against us, and in so doing resorted to the abominable expedient, charging Varshafsky with the notoriously slanderous accusation of being a “Russian agent.” There were among them men who had long stood in friendly relations to the leaders of the International–Engels, Wilhelm Liebknecht; so they had no difficulty in presenting the matter in such a light as made us appear a band of intriguers, destroying the unity of Polish socialism. In spite of Rosa Luxemburg’s brilliant oration in refutation of this lii, the congress decided to reject the mandates, both Rosa’s and Varshafsky’s. Plekhanoff played a very shabby part in all this procedure: he was well acquainted with Polish affairs, and one word from this popular member of the International would have sufficed to unmask the intrigue, but he preferred to keep silent and afterwards confessed that it was awkward for him to oppose the opinion of old Engels. Such things unfortunately occurred later more than once in the Second International: things were often decided there in accordance with the sympathies or antipathies of popular leaders. We were defeated, but still interest was awakened in the International on questions of Polish socialism and we were enabled to explain them in the French and German press. This task also fell mainly to the share of Rosa Luxemburg.

The elaboration of questions of the Polish labour movement kept advancing and the movement itself was gaining strength. During these years Rosa Luxemburg attended university lectures, and in 1897, wrote a brilliant doctor’s dissertation of the theme: The growth of Polish industry. In the seminary she was distinguished not only for sound knowledge, but also for brilliant dialectics, which showed in frequent disputes with the professor of political economy, Julian Wolf, a vehement adversary of Marxism. We simply [unreadable] amusement. I would entice the respected professor with slippery theme, then we, clad in the full panoply of Marxism, would demonstrate to him that he knew nothing of such matters. We must do justice to the Zürich university to admit that, notwithstanding our aggressive attitude, the faculty placed no obstacles in the way of our both obtaining the doctor’s degree.

In 1897 Rosa Luxemburg graduated from the university and decided to go to Germany in order to have the possibility of open social activity, she contracted a fictitious alliance with one of Dr. Lübeck’s sons, and, in this manner, became a German subject. Sho worked among the Polish workers in Posnagne and Silesia, and at the same me wrote in the German papers in the scientific organ of the party, the Neue Zeit. I had gone to Germany the year before and worked in Dresden, in an organ, the editor of which was Parvus. But in 1899 we were both expelled from Saxony, and Rosa was appointed editor of a Dresden paper, where discord forced her to abandon it and she soon became a contributor to the Leipziger Volk Zeitung the editor of which was the then best German journalist Schönlang. After his death she edited his organ for some time.

That was a time when a crisis began in the German labour movement: Bernstein came forward and propagated revisionism. Rosa Luxemburg rushed into polemics, and her brilliant articles helped to determine the tactical line. Questions of tactics soon became vital for the whole of Europe: there arose questions of participation of socialists in bourgeois governments and generally a sharp conflict began between the reformists and the revolutionist currents. In this conflict Rosa Luxemburg’s great dialectical and polemical talent manifested itself in all its force: she soon became one of the most prominent champions of the revolutionary tendency. The Polish Social-democratic party appointed her a member of the international bureau, and from that time on, she carried on an uninterrupted war for revolutionary ideas on the widest possible arena. Here again Jogihes was her inseparable fellow worker. The intimate acquaintances of Rosa Luxemburg will know that she never sent to press one polemical or programme article without first submitting it to him. Nor did the two comrades neglect the work for the Polish movement. Luxemburg’s apartment in Friedenau (a suburb of Berlin), was the centre to which comrades arriving from Warsaw, were sent to seek counsel on all new questions as they sprang up; thither also came Comrade Jogihes, in the hands of whom were the threads uniting the party at home with the emigrated comrades who worked for it abroad.

Thus, in constant fight for the revolutionary idea, passed the years from 1897 to 1905. Al through this struggle Rosa Luxemburg rendered the proletariat immortal services, diverging not one step from the clearly traced line of revolutionary Marxism. A characteristic feature of her personality was that notwithstanding the merciless, at times even excessive, keenness of her polemics, her eminent opponents, among whom sometimes were such men as Jaurès and Bebel, showed her not only respect, but affection. A bond of closest friendship united her to Kautsky, over whom she had great influence at the time, urging him on whenever he gave way to opportunistic tendencies.

Then came the Russian revolution of 1905-1906 and, in that deadly fray the Polish proletariat proved a reliable vanguard. Comrade Jogihes hastened to Warsaw; Rosa Luxemburg also longed to be there. Vainly wo all declared that she must stay in Berlin, as we needed her scientific work. In spite of our categorical declarations she arrived in Warsaw one fine morning with a German passport. Tyszka (that was the alias under which Jogihes then went), was indignant, but he had to submit. Rosa declared that nothing would make her leave her post, and set to work in our paper.

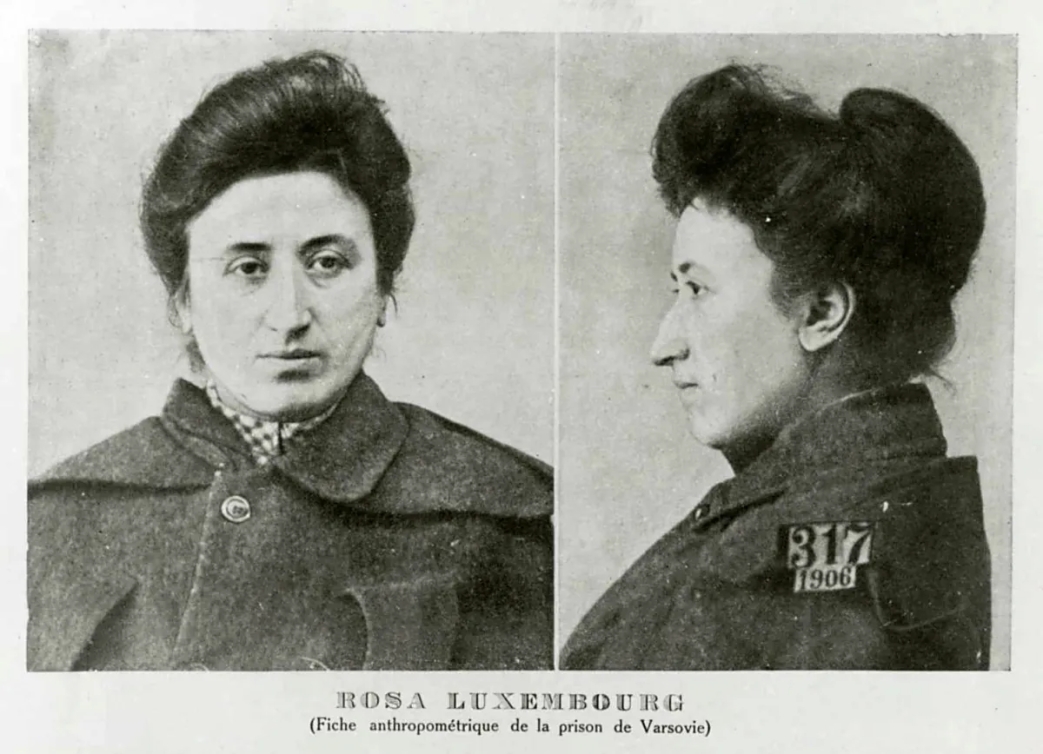

But alas, not for long. A few weeks later she fell into the hands of the police, and her identity was soon established. Fortunately even among the police disintegration had already set in. A threat of dire vengeance on one side, and a bribe on the other succeeded in getting her freed on bail, and soon after the comrades sent her back to Germany. She protested, but this time we were firm.

Tyszka was taken along with her. If had, all along, been doing splendid work. Thanks to him our paper was coming on beautifully: He had established the editorial office in a conspirative apartment situated in the centre of the city and kept up the strictest régime. As usual, he did not write himself; but not only each article almost every short item was written according to his indications, so that every issue should be, from beginning to end, as cut out of one piece, —but not a line was printed that was not before submitted to him. He kept his contributors under strict discipline, admitting no excuses on the plea of either fatigue or disinclination: You’ve got to work, that’s all there is about it. And, seeing how indefatigably he laboured from morning till night, all willingly entered into this wonderfully organized work. Nor was his vigilance confined to the literary brotherhood only: he was merciless on typographical or technical imperfections of any kind: Heaven help us, if another typo was used than the one indicated on the manuscript for this or that short item, or any issue which did not answer all the demands of the. printer’s art. and any mismanagement in the transport department, it was an unthinkable crime. The luckless offender would, sometimes after a month’s interval, be reminded that, at such and such a time, five copies had been late in reaching their destination. There was nothing he did not remember; nobody he did not keep track of. Yet, in addition to his editorial duties, he had an immense amount of organising work to attend to. He thoroughly knew the whole course of party work the smallest details and marked all with unwearying vigilance. But this sedulous attention to trifles did not impair the wide scope of his vision, and in all questions of tactics he was distinguished by remarkable hearing and foresight.

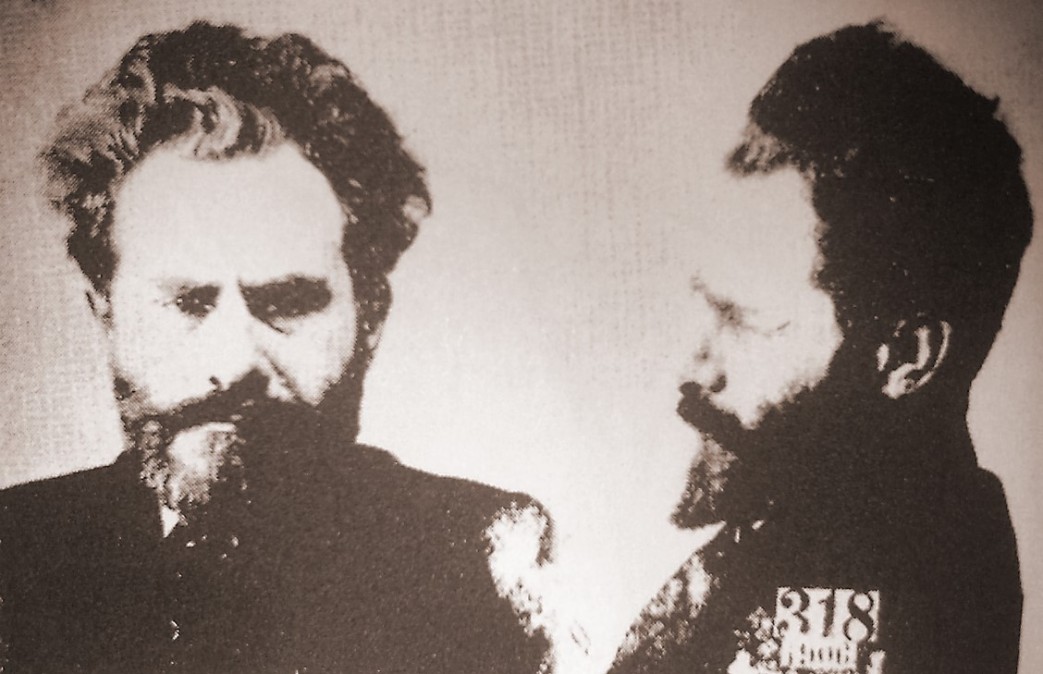

He was arrested in February, 1906, together with Rosa Luxemburg, and sentenced to eight years of prison with hard labour. In February, 1907, however, the comrades arranged his flight from prison. Comrade Ganetzky made all the preparations: the guards were bribed, clothes procured, and the prisoner got away. I remember how he came to the office straight from prison, where he had to stay several days until a safer refuge could he provided. Affairs in the office were not as successful as they had been, the contributors were nearly all in confinement, the process of printing grew more and more difficult, and our paper had lost much of its neatness. Tyszka immediately asked for a paper, glanced through it, and was horrified: countless misprints. I pointed out that Limshat, the proofreader frequently had to work in the basement, sitting under the machine. But this did not concern him: “Proofreading”, he said, “requires a head aid hands; so long as the man’s head is on his shoulder and his hand is able to hold a pencil, it does not matter where he sits.” Indeed, Tyszka himself was quite capable of working under such conditions. Then he sat down and drew up a series of instructions which appeared him necessary for the improvement of affairs. He was taken to the frontier, I remember, by a revolutionary army officer, and, after safely crossing it, he at once set to work directing the foreign group’s activity, which was gathering importance in proportion as the count-revolution was gaining ground in Poland and all over Russia.

I met him again abroad the London congress of the Russian social democrat party in the Sumner of 1907. The struggle was made against the “minimalists” (Mensheviks), and Tyszka, who through all these years had not lost touch with the Russian comrades, quite naturally took the lead of the Polish group. He was familiar with Russian affairs the minutest details, and took the most active part in the complex work, which was required at the congress, where affairs were in monstrous tangle. In such cases, he became a “diplomat,” persistent and determined in pursuing his ends, never for a moment swerving from strictly revolutionary line of conduct. In this regard he was, of course, anything but a favourite with the Mensheviks, and Bundists.” True, it sometimes also came to quarrels with our “Bolshevik” (maximalist) comrades with whom we differed on questions of organization. It is thanks to the balance preserved by Tyszka, the relations between them and the Polish group always remained satisfactory.

From 1907 on Rosa Luxemburg was drawn wholly into German affairs. We were nearing the fatal period when, outwardly, all seemed well with the party, while, in reality, it was decaying at the root. It seemed as though the radical current had triumphed; the party congresses adopted highly radical resolutions, but they whose eyes were open, perceived that this radicalism was essentially worse than any opportunism: a disgusting spirit of career-hunting was developing in the party; party bureaucracy was growing to monstrous dimensions: there was the radical phrases but not the spirit. To combat these conditions, which at last led the party to the moral catastrophe of the 194h of August, 1914, was very difficult. Of the most influential leaders old Bebel had lost his former revolutionary sensitiveness: Karl Kautzky never having been in such with the life of the party, now sank ever more deeply into bookish dogmatism. The new men in the ranks of the radicals—all these Scheidemanns, Eberts, Noskes, never had been revolutionists at heart, and see nothing beyond the end of their own noses: the rest were common career hunters. No wonder, then if in such an atmosphere, the leaders succeeded in representing Rosa Luxemburg, who never ceased to sound the alarm, and her companions as captious critics, who disturb the peace of the party from sheer, “love of bickering”…Even Kautzky yielded to this current and his conduct in 1912 ended a long friendship. The weak-minded bookworm at last dared to insult Rosa and her adherents by calling them “anarcho-syndicalists.”

Notwithstanding this never-ending conflict, Rosa in these last years found time for thorough scientific work. She was appointed teacher of political economy in the party school, and proved not only a first-class pedagogue, but, in addition, while most arduously preparing her lectures, wrote a splendid course of Marxist economy, which unfortunately never appeared in print. (it is to be feared that Noske’s bandits who in the fatal January days invaded her rooms, destroyed this manuscript among many others). At that same me another great work of Rosa’s was published, The Accumulation of Capital.

At the same time these were the most fruitful years of her activity. The persecution of Rosa Luxemburg by the heads of the Party had no effect on the masses. In every city, even in the centres of revisionism: the workers loved to hear our Rosa; and her captivating oratorial talent affected even on those who were already infected with opportunism. I remember one man from Mannheim, I believe, telling what extraordinary effect her speeches produced: how on one occasion the workingmen declared to their leaders they saw how they were being deceived, and demanded that Luxemburg be engaged for a whole series of lectures and disputes on party questions. Of such cases there were many.

In 1913, in Frankfurt-on-the-Main, she delivered a speech against militarism, for which she was indicted and eventually sentenced to year in prison. But, during the period of bail, before sentence, she delivered another speech in Berlin, where she said, among there she said, among other things, that in the barracks of Germany, the soldiers were daily subjected to inhuman violence and outrages. For this a new indictment was instituted against her. The defence undertook to prove the truth of the incriminated statement and culled for witnesses through the papers. In June, 1913 [1914?], a few weeks before the beginning of the world-wars the trial began; on the day of the first hearing, sever hundred witnesses appeared, ready to confirm all it had been told of barrack horrors and Rosa’s counsel declared that he had the names of several thousands more.

The government took alarm; the trial was adjourned and never continued again.

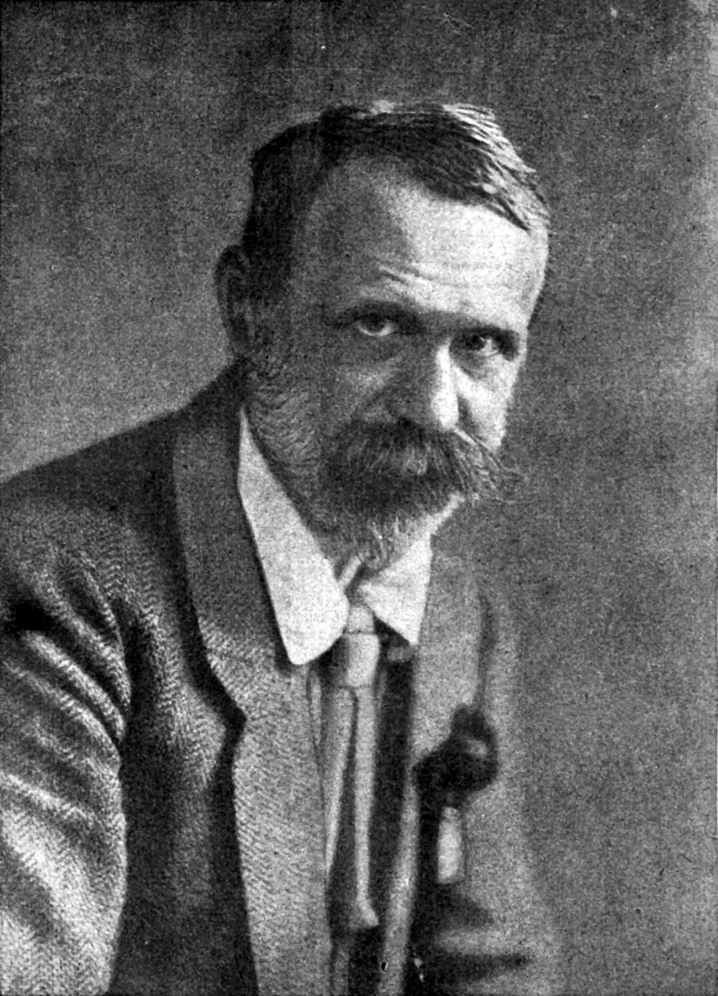

During these years Comrade Tyszka worked in the Polish and Russian parties. They began to issue in Warsaw a legal weekly, but all the party writers having been compelled to emigrate, the editorial work was carried on in Berlin and Tyszka, of course, was at its bead. He was then staying at a hotel in Steglitz, suburb of Berlin, and Franz Mehring, a great authority on Prussian history, made the discovery that this hotel had once been the palace of General Brangel, who put down the revolution of 1848. Each time he saw Tyszka, the old scholar affirmed that Brangel invariably turned round in his grave at the thought of such a revolutionist occupying his apartment. Our editorial office was established in a small room of the hotel, and here again Tyszka introduced a strict régime, storming angrily if the work were at all unsatisfactory. And, indeed, it was only by the greatest accuracy that the paper could be managed from Berlin, a thing that the literary crowd was incapable of doing. Still, owing to Tyszka’s energy, things went on, notwithstanding that the paper continually being suppressed and appearing again under new names; for the year that the paper existed, it changed its name, if I remember aright, seven times.

The reason why Tyszka had to work in the Russian party was that he had been appointed by the Polish party, —which had become a federative part of the Russian party, as a member of the Central Committee. And, being pedantically accurate in all his work, he found it necessary to keep the Board of the Polish party informed with all common affairs; in view of the periodical assembly of the party in Berlin, he had to do all the clerical work, and do it alone under intolerable condition; he lived under an assumed name, the police might be down on him any moment; therefore the “office” was kept in the apartments of German comrades, where the papers were kept, and for correspondence he had the addresses of other Germans. Once we totaled up that Tyszka had, in this way dealings with something like a dozen different apartments. He maintained this system for conspirative reasons; he said his materials were distributed in such a way that, even should our place he ransacked, the police would find but a small portion of them, from which they could know absolutely nothing. Once I asked: “what would happen if he were taken suddenly ill, since no one would be capable of carrying on the work?” The answer was simple: “I am not supposed to fall ill.” And in fact nothing but an astonishing capacity for work and an iron constitution made it possible for him to get through with the mountains of work with which he loaded himself.

The war broke out. From the very first day Comrade Luxemburg started a propaganda against war. She expected to succeed in gathering together for joint work a select group of German comrades. The first thing that appeared needful to her was a manifesto, signed, if only by a small number of people most popular among the working classes. Tyszka at once decided that nothing would come of it. Nevertheless Rosa and I made an attempt. But in reply to her invitation to discuss the question, only seven persons assembled in her rooms, and of those only two were at all prominent party workers: Mehring and Lentsch. The latter at first promised to sign, but afterwards went back on his word. There was nothing to do except that it should be signed only by Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin and Mehring: this, of course, was not to be thought of and the project had to be abandoned. A reader unfamiliar with German affairs will possibly ask: And what of Liebknecht? Unfortunately Liebknecht was still wavering at that time, and it was only some months later that he made up his wind to enter the struggle against the war.

We had to decide on conspirative activity; and even to this very few agreed. The group which took up the work consisted of Comrades Luxemburg, Tyszka, Mehring, wife of Dunker, Ernst Meyer, Wilhelm Pick, Eberlein, Lange and myself — that, I believe, was all. Our assistants in “technical work” were Mathilde Jakob and Yezersky. The position was not encouraging; we had neither money nor party machinery, and besides that, the German comrades had not an inkling of conspirative work. Still, the thing was begun. Tyszka and Meyer undertook to manage the printing. Peick, Eberlein and Lange, with the help of their connections, offered the possibility of the diffusion of the literature, but very soon it was Tyszka again who had to take charge of both these department. Thus we were enabled to issue a series of leaflets against the war. In addition we decided to take up the publication of a legal journal: The International, but it was suppressed after the very first issue.

In February, 1915, the sentence against Rosa Luxemburg was confirmed and she was confined in prison for a year. Still, she contrived to write and smuggle to us, principally through the agency of her able and devoted worshipper, Mathilde Jakob, leaflets and a pamphlet, under the title: “The Crisis of Social Democracy.” She insisted that the pamphlet be published under her own name, but we knew that would mean prison with hard labour and refused. The pamphlet bore the pseudonym of Junius.

The term of imprisonment expired; Rosa once more appeared in our ranks. Now Liebknecht was also with us, and things went on on a larger scale. But already in June, 1916, she was again imprisoned, by “administrative order.” I too was confined at the time in a “concentration camp,” but I know that Rosa even then managed to write leaflets, which appeared under the title: Letters of a Spartacist. I also know that the printing and propagation of these leaflets was wonderfully provided for, owing first of all to Tyszka’s incredible energy. Thanks to his matchless conspirative capacity, the German authorities never succeeded in arresting him, notwithstanding the fact that, in consequence of nearly all the capable workers of the Spartakus group having been either arrested or sent to the front, he was forced to work in pretty wide circles and attend public meetings, Thus it was well known to the police that some mysterious foreigner was at the head of that group. But in the spring of 1918 Jogihes was arrested after all. Comrade Yoffe’s efforts to have him liberated did not meet with success, because Jogihes was reckoned as a Swies citizen (In fact, as early as 1896, he had acquired the rights of citizenship in one of the cantons and for the last years had been using his Swiss passport in Berlin).

I was not fated to meet Rosa Luxemburg again. I arrived in Berlin from Moscow on the third day after the catastrophe. But what I was told by the participators in the revolutionary struggle did but confirm what I had never doubted: she, joined with Karl Liebknecht, had been the leading spirit of Spartacus movement, and her unshrinking fellow worker through all that time had been Jogihes. I found him at work. He had been arrested in the days of the January rising, but had managed to get free and went to work at once. It was urgent to concentrate again the scattered forces, to furnish anew a central Committee of Spartacist-communists, in short to construct an organization.

Jogihes proved equal to the occasion. Owing to his energy, the party’s work was renewed almost immediately after the catastrophe. There was a new rising of the communists in March, during, which he finally succumbed: he was arrested and brutally killed in prison.

I am not in a position just how to give a review of Rosa Luxemburg’s scientific al political work. That would demand much historico-critical labour, the more so that her activity during a considerable period fecundated both the Polish and the German revolutionary movement and, besides that, reacted on the universal movement, as the principal forces of our never to be forgotten comrade, ever since 1897, were directed in the struggle against opportunism as an international evil.

But I will draw the reader attention to the fact that, in her last theoretical-tactical work, in the pamphlet entitled “The Crisis of Social Democracy”, she left us valuable directions for future work: I am speaking about the Theses placed at the end of that pamphlet and concerning the International. The pamphlet, as mentioned above, was written in 1915, in prison. Her thorough knowledge of the Second International prompted her clear and positive statement on the inevitable dissolution of the Second Internation: and the absolute necessity of creating a now International on new principles: Since that time there have been great changes: the revolution in Russia and the actual realisation of the dictatorship of the proletariat in that country and in Hungary have created a new situation. But on the whole Comrade Luxemburg’s idea remain true. She asks herself what the new International should be and gives the following answer:

“Class war in bourgeois states against the ruling classes, and international solidarity between the proletarians of all countries, — these are two inseparable rules of the workers in their universal struggle for liberty.

“There is no socialism without the international solidarity of the proletariat; there is no socialism without class war. The socialist proletariat cannot, in time of either peace or war, renounce class conflict and international solidarity without being suicidally untrue to itself.

“In the International lies the centre of gravity of the class organization of the proletarian The International defines, in time both of peace and of war, the tactics of national sections in questions of militarism, of colonial policy, of commercial treaties, of first of May celebrations,

“The duty of and of the general tactics in case of war. executing the decisions of the International takes precedence of all duties to any other organization. Any national sections that do not submit to these decisions, thereby exclude themselves from the International.”

At present we are still far from the organization of such an International, but by working in this direction, we fulfill the behest of the memorable martyr of our cause.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF pf full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n03-jul-1919-CI-grn-goog-r2.pdf