A rail worker militant of the Socialist Labor Party writes on the history of union organizing among switchmen. Particularly interesting because of its ‘left’ critique of Debs and the American Railway Union attempts in the 1890s to form an industrial union in rail outside the Brotherhoods.

‘The Railroad Switchmen’ from The Weekly People. Vol. 13 No. 34. November 21, 1903.

By the term switchmen is meant the men engaged in yard service in the various railroads of the country. Night and day these men are engaged in making up trains, and spotting cars at the various points. The men work in crews, foreman and two or three helpers, or brakemen, constitute a yard crew. Their work is one of extreme danger. Insurance companies refuse to accept them as risks, or charge them such exorbitant rates that insurance becomes practically prohibitive.

In 1881, a local union of yardmen was formed in Chicago. They went on strike and secured what is known as the old Chicago standard rate, $2.50 days, $2.70 nights for helpers; $2.70 lays and $2.90 nights for foremen.

Local unions were formed in Rock Island, Ill.; Kansas City, Houston, and A few other places. They existed locally without any national cohesion until the year 1886, when the various locals sent delegates to Chicago and formed what is known as “The Switchmen’s Mutual Aid Association,” with Monahan as Grand Master, and Crawford as Secretary Treasurer.

At the end of one year Crawford secured a position from the capitalist government as superintendent of the Bridewell workhouse, and Condon was elected secretary. He soon left with the funds of the union, and he disappeared and hasn’t been heard from since. Then William A. Sinnott became the secretary-treasurer.

Monaghan, in the meantime, on the strength of his prestige as Grand Master of the Switchmen, actively engaged in local politics in Chicago, and secured a good position under Carter Harrison, Sr. He resigned as Grand Master, and Frank Sweeny was elected in his place.

In 1887 the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakemen changed their constitution so as to admit the yardmen to membership. They had a very large percentage of the yardmen of the Eastern States as members, and they claimed jurisdiction over all the yards in the country.

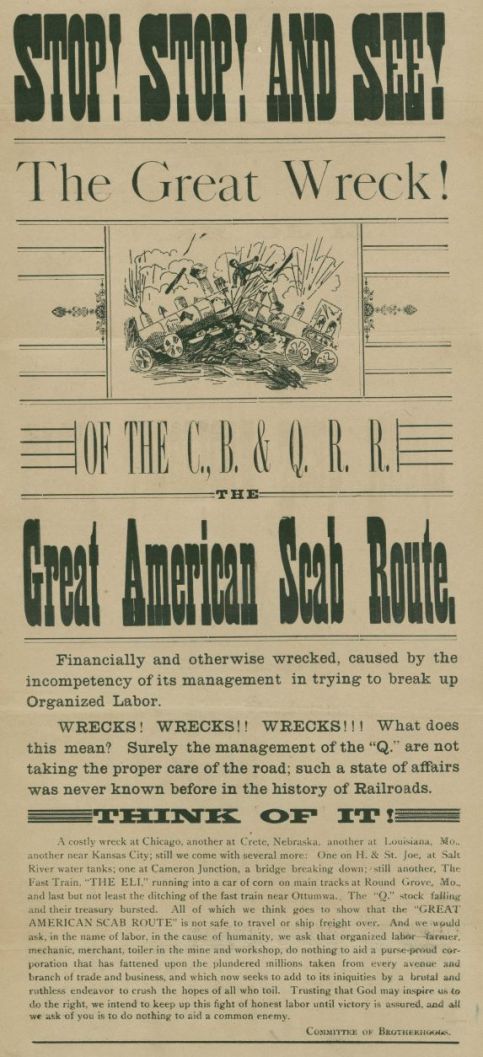

The switchmen of the West, owing to their well-known proclivity of going on strike in sympathy with any organization fell in disfavor with the managers of the western roads. The switchmen on the C.B. & Q. railroad went out on a sympathetic strike with the engineers and firemen’s brotherhood. They lost heavily, as out of 650 striking switchmen not one was re-engaged on the entire system. But the loss to the Burlington system, from a monetary standpoint, was very great, and the roads preferred to grant the demands of the switchmen in preference to fighting them.

The Chicago and Northwestern Railroad was the strongest organized road in the West at this period. While all other departments of the service were satisfied to receive their pay for the previous month on the twentieth, the switchmen declined to wait twenty days for their money and forced the company to pay them on the seventh day of each month. Now, in 1890 there was trouble between the switchmen’s union and the trainmen’s brotherhood. A man named McInerny, who remained at work during Every strike of the Switchmen’s Union, was admitted to membership in the trainmen’s brotherhood. He was classed as a scab by the switchmen, and one day he exceeded his brief authority as assistant yardmaster by discharging switchman whose duties were on a different division. The switchmen promptly asked for the reinstatement of the discharged man. and for McInerny’s their discharge, which was granted.

P.H. Morrissey, who is now the trainmen’s Grand Master, at a salary of $5,000 per year, and expenses, entered into an agreement with the Northwestern Railroad to replace the fighting switchmen with a more docile set of slaves. The wages in Philadelphia at that time was $1.60 to $1.80 per day of twelve hours, $2.50 and $2.70 for ten hours were riches to these pure-and-simplers. They agreed to fill the places of the striking Chicago men. On May 14th, the switchmen’s ultimatum for increased wages from the C. & N.W. was up, and the switchmen were to strike on the 15th at 7 a.m., each and every switchman’s place was filled by a trainman, and the switchmen were discharged, locked out. The railroad’s ample police protection, and the power of the switchmen were broken.

In 1893 the switchmen around Chicago demanded increased wages, but three of the largest yards were scabbed, the C.B. and Q., the C. and N.W., and the Lake Shore. The matter fell through, and hundreds of switchmen throughout the country saw the Switchmen’s Union was powerless, and so dropped out.

About this time the panic of 1893 started. The railroads of the country forced a reduction of wages on all classes of employes, except the switchmen. The Great Northern led the way with two reductions in wages in the transportation department inside of three months, and the ship and section men were reduced as much as 40 per cent.; the Santa Fe, Big Four, Wabash, C. and O., and in fact, nearly every road reduced wages. Discontent was in the air.

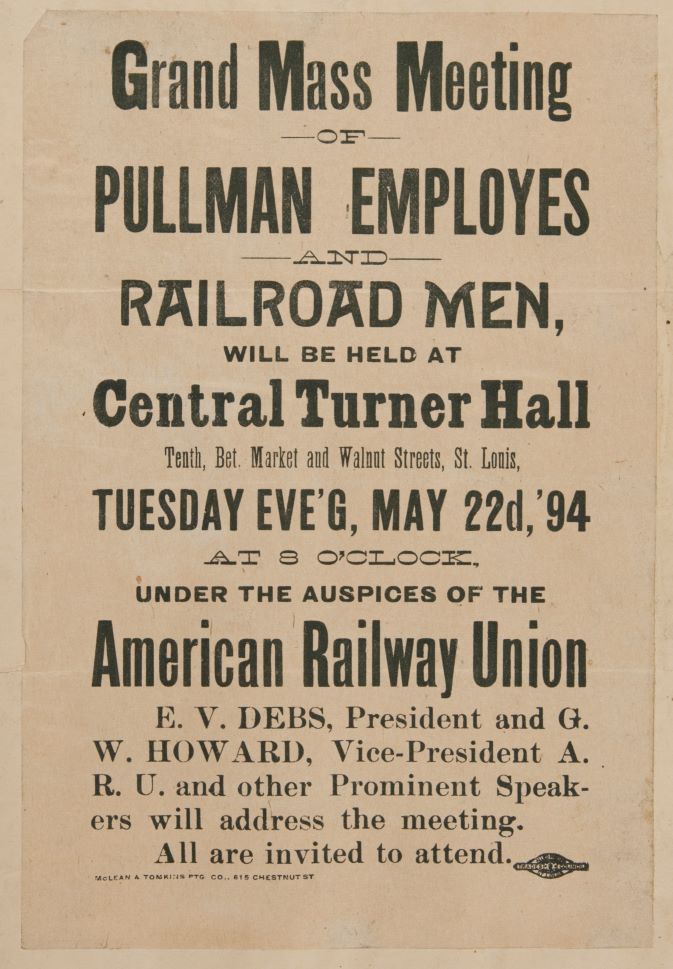

Eugene V. Debs, who wanted to become Grand Master of Firemen’s Brotherhood, at their Harrisburg convention, could not secure the position. The delegates claimed he was “too radical,” and he refused to accept the position of secretary-treasurer, and editor of their journal, to which he was elected by them. Instead he only accepted the position of editor of their journal so as to propagate his ideas.

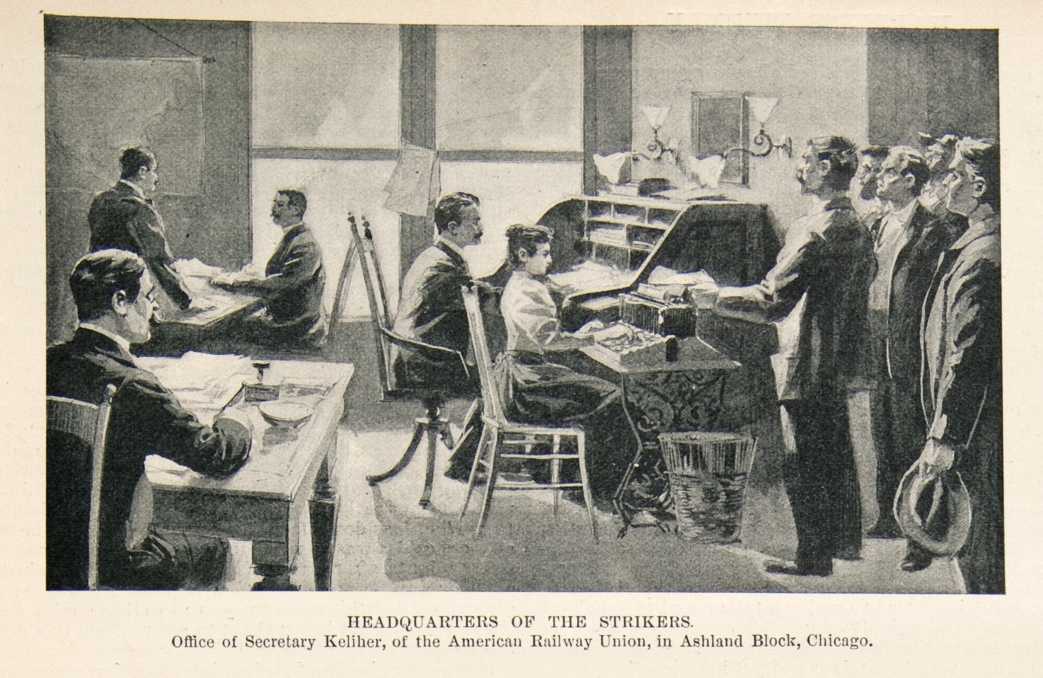

Debs gave out various hints that he intended to organize a vast industrial railroad union In November, 1893, a mass meeting was called in Battery B’s Armory, and Local Union No. 1 of the American Railway Union was formed. Among the self-appointed directors were L.W. Rodgers, who was the former editor and manager of the Trainmen’s Journal, and who was expelled by the Galesburg Lodge, B.R.T., because he came out in the Trainmen’s Journal and said, “Any man who took the place of a striking or locked-out switchman on the C. & N.W. system was a scab, whether sanctioned by an organization or not Sylvester Kelliher, who saw the Brotherhood of Railroad Carmen about to expire anyway the dues wouldn’t pay the salaries of the grand officers, so he joined forces with Debs and was made secretary. Treasurer George B. Howard, who was a labor fakir out of a job, as the Brotherhood of Railroad Conductors had amalgamated with the Order of Railroad Conductors, and threw him out of a position (He was quite popular with the employees on the old Mackey lines in Indiana, where he led a successful strike among the employers). He was the last of the big four who founded the American Railway Union.

Debs was intensely popular with the firemen and also the switchmen, as he voted to expel the B.R.T. for scabbing on the C.N.W.

The A.R.U. was thus formed. The western switchmen went into the new union in overwhelming numbers. Union after union was formed.

The grand officers of the Brotherhood of Engineers and Firemen on the Great Northern accepted a wage reduction in spite of the protests of two-thirds of the men on the system. Here was the golden opportunity of Debs. Using his skeleton unions for a base he called a strike on the Great Northern of all employees. They obeyed him.

The grand masters of the engineers, firemen, conductors, trainmen and operators, ordered their members to return to work under pain of expulsion from their organizations, and also threatened to fill their places with union men from other roads. The men thoroughly aroused, stood firm. The Great Northern employees were out to a man. James Hill recognized the American Railway Union. Using the prestige of this victory, the organization spread like wildfire in the West.

Wm. A. Simsrott, the secretary-treasurer of the Switchmen’s Union, saw the membership of the union decreasing so rapidly that the organization was practically dying, entered into a deal with Grand Master John E. Wilson, whereby, Simsrott’s bond, put up by Dr. Murdock, the grand medical examiner, was invalidated, he took $50,000, and the Switchmen’s Mutual Aid Association died. Not one penny was collected from his bondsman, and Simrott opened a saloon and drank himself to death.

The switchmen of the West were now in the American Railway Union. G.W. Howard went out to Pullman and organized the Pullman palace car workers into the A.R.U. They struck. George M. Pullman refused to give in. The A.R.U. membership of 50,000 could not support the idle eight thousand men on strike; eight thousand couldn’t live on forty thousand. The old brotherhoods refused to give any financial aid, as the success of the A.R.U. meant the disruption of their organizations and consequently a loss of high salaried positions.

The unions outside of railroads gave lots of sympathy and moral support, but no cash, or rather all the unions in the United States outside of the railroad unions contributed just $5,050.25 in two months.

Defeat was staring the A.R.U. in the face. The men at Pullman threatened to return to work, the prestige of the victory on the Great Northern Railway, would be lost in the shuffle of a Pullman defeat. Something had to be done.

The A.R.U. convention was about to take place at Chicago. A circular was sent out by the board of directors of the American Railway Union, asking the members to vote on a proposition to instruct their delegates to vote for a boycott on all Pullman cars. The delegates were so instructed, the convention met, Debs made an ambiguous speech to the delegates in which these words occurred: “I am not going to advocate a boycott, to be enforced by a strike. if necessary, but these striking employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company, are members of the American Railway Union, and among its members there is none so oppressed as these men. They are entitled to your support, even to the extent of stopping the wheels of commerce on all roads in the United States. I am not going to advise you to do one thing or the other, but will only say before leaving the hall, consult your own conscience, use your reason, and I am sure that you will not desert these striking employees in this, our hour of greatest need.”

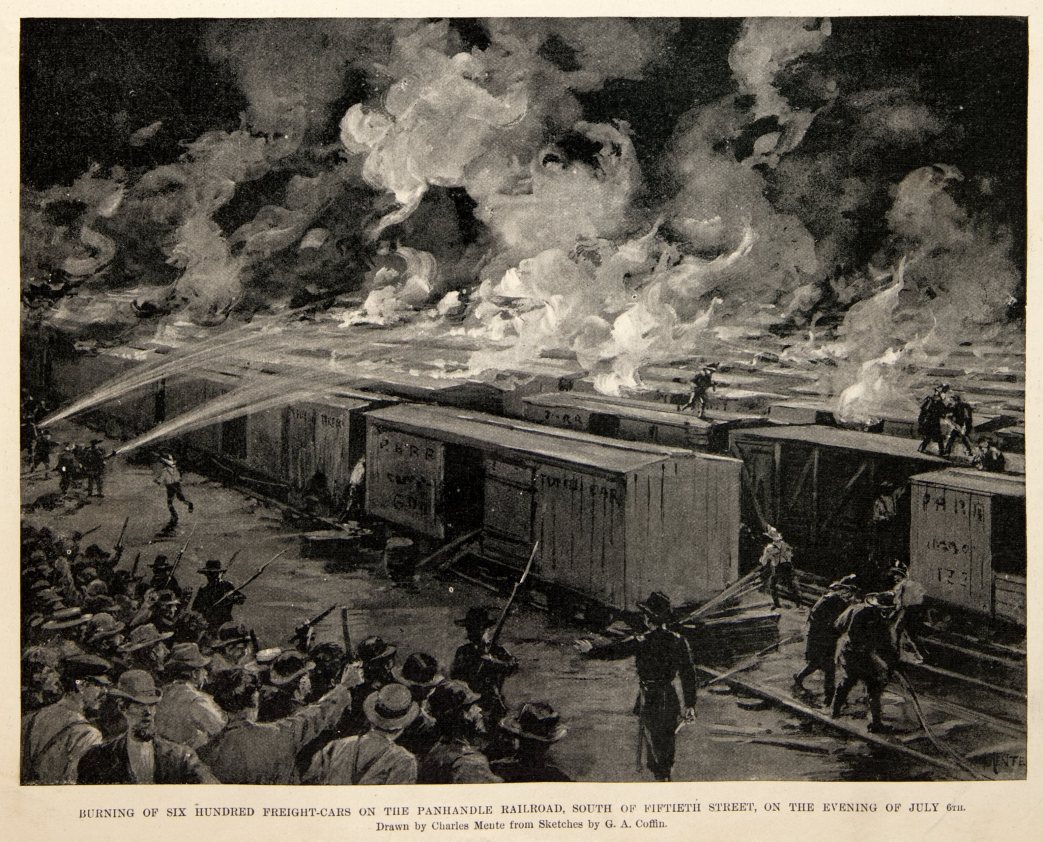

Debs left the hall. George W. Howard took the chair and made a ringing speech, advocating a strike and boycott; so did Rodgers, so did Goodwin, and it was unanimously carried that on and after Tuesday afternoon, at 2, June 26, 1894, no member of the American Railway Union should handle a Pullman car.

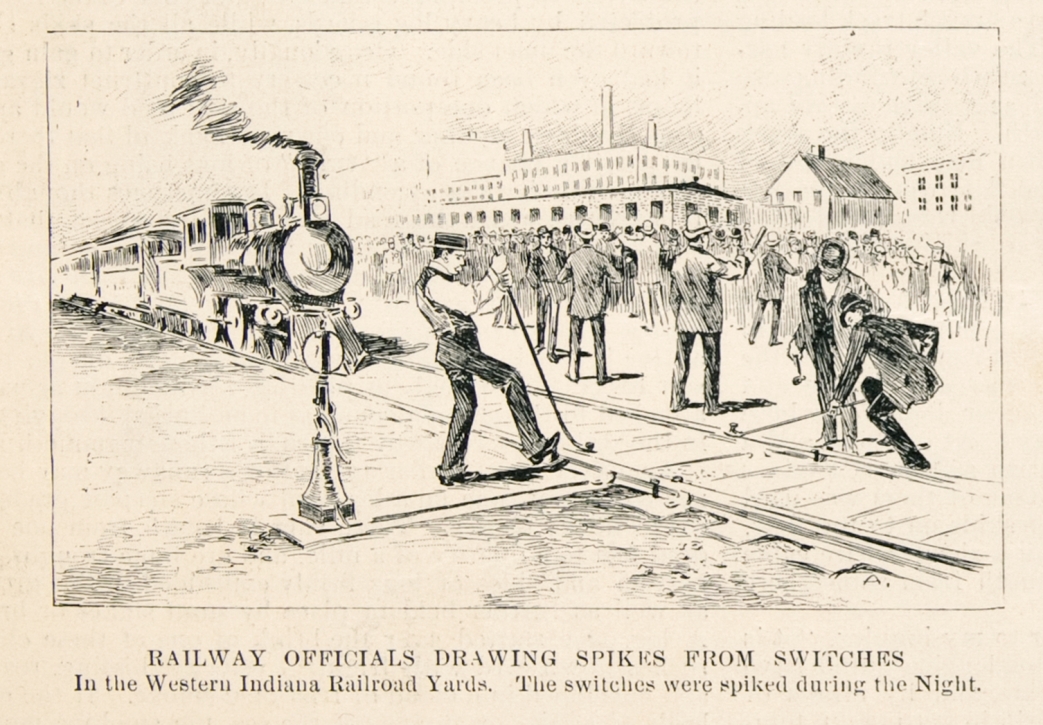

A young switch tender at Fordham refused to throw a switch for a train on the Illinois Central Railway. He was discharged. The strike started all over the western country.

In some places where the A.R.U. had no membership the men refused to strike. In Chicago the men generally went out.

Pretty soon the grand masters appeared on the scene, and ordered the men back to work. The majority said they would work if assured protection. Governor Altgeld refused troops, as no disorder had occurred. Mayor Hopkins, who was a discharged official of the Pullman Company openly showed his resentment at Mr. Pullman, and made political capital out of the strike by sympathizing with the strikers. Cleveland sent the troops to Chicago at the request of the General Managers’ Association.

The grand masters, Arthur, Sargent, Clark and Morrissey, openly said that the men who went to work during this strike would not be called scabs. Arthur sent all the idle engineers he could get to the various roads, nearly all the striking engineers of the Lehigh Valley, Ann Arbor and C.B. & Q. railroads, who were blacklisted by those roads, secured positions. Also vast numbers of discharged engineers from other railroads, who were compelled to work as mortormen and conductors on street cars, stationary engineers and other paying positions, secured a new start in life. They went to work with the full sanction of their brotherhood. Clark of the O.R.C. furnished conductors, Morrissey of the Trainmen furnished brakemen, conductors and switchmen. The strike was broken.

There was a general stampede for jobs on the part of engineers, firemen, conductors and trainmen, whose places were filled. Men who struck and lost their positions on one road, openly and secretly scabbed the positions of other men. The battle all over the western country resolved itself into a switchmen’s battle. The trained warriors of the industrial field stood firm. The strike was lost, still the switchmen awaited the word from Debs, declaring the strike off. No word came.

All other classes of men returned to work, still the switchmen stood firm. Debs couldn’t be found; he was drunk, the Chicago papers said.

At last he came out from his three days’ retirement. He called on Samuel Gompers for aid. Sammy came; he saw and went back to the headquarters of the A.F. of L. and said he could give no aid.

On August 6, the switchmen met, they admitted defeat and declared the strike off at 6 a.m., August 7, 1894, except on the Santa Fe, Wabash, C. & E.I. and Chicago & Great Western roads: Debs tragedy had run its course, the strike was history.

There were several places where the switchmen refused to obey the orders of the A.R.U. to strike, as they claimed that they were not members of the A.R.U. and Debs had no business to order them out.

The strike never extended east of Cleveland, and only lasted a day in Cleveland, when the switchmen, noticing how the other branches of railroad men were working, saw the futility of fighting alone and returned to work. These men formed the nucleus of the new Switchmen’s Union.

Instead of seeing how the powers of government was used by the capitalist class to down them, and organizing on a new trades union basis, they organized once more on a pure and simple basis. The vast majority of the switchmen joined the B.R.T., but failing to get any benefits out of them but death and accident insurance, began leaving the trainmen in large numbers and rejoining the S.U. But of those that had joined a large number remained in the trainmen, as the switchmen had no insurance.

Labor fakirs made their appearance in the organization, and John E. Tipton, the secretary-treasurer, was given five years in Auburn for embezzling $1,800 of the union funds.

The Milwaukee convention established an insurance, the membership increased. They struck on the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. The Brotherhood of Trainmen and Order of Conductors openly scabbed the jobs, even to the ex- tent of making their members, in what is known in railroad parlance, “Scab in their turn,” by issuing this order: “Crews first out before 6 a.m. work during the day in the yard and then go to the foot of the list. same as though they made a trip on the road, and those first out before 6 p.m. do the same thing at night.” The same thing happened later, and more recently at New York (Harlem River) and at Pittsburg, they furnished men to fill switchmen’s places.

Can the switchmen not see that the pure and simple brotherhoods are but scab furnishing agencies for the railroad companies?

Can the railroad men not see them signing contracts that increase wages 30 cents a day, while taking a man off each engine, as was done recently on the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railroad?

Can the railroad men not see that the railroads are gradually intensifying labor, as was recently done on the Northern Pacific Railroad, at Tacoma, where they pulled off four car inspectors, and want the foreman of a switch engine to make out an accident report of all “bad order” cars handled by him?

Can’t the railroad men notice the age limit of twenty-eight on the Pennsylvania, the age limit of thirty and thirty-five years on various roads, the physical examinations on the Lake Shore, P. & L.E., C. & N.W., Union Pacific, Southern Pacific and various other roads that I won’t employ you if you have a finger or joint of a finger off?

Switchmen, you stand to-day as the only organization in railway service that has never sanctioned scabbing in any form. Are you going to continue voting for your oppressors? It is your duty to join the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance. Read the Weekly People, and find out where your class interests lie. Instead of organizing to demand a portion of that which you produce, demand it all. Pay no attention to the misleaders of labor. You recognized at your convention in Indianapolis the fakirs in the A.F. of L. and refused them the floor. Use your votes and influence for the party of labor, the Socialist Labor Party and speed the day when capitalism is overthrown.

A Switchman.

New York Labor News Company was the publishing house of the Socialist Labor Party and their paper The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel De Leon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by De Leon who held the position until his death in 1914. Morris Hillquit and Henry Slobodin, future leaders of the Socialist Party of America were writers before their split from the SLP in 1899. For a while there were two SLPs and two Peoples, requiring a legal case to determine ownership. Eventual the anti-De Leonist produced what would become the New York Call and became the Social Democratic, later Socialist, Party. The De Leonist The People continued publishing until 2008.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/031121-weeklypeople-v13n34.pdf