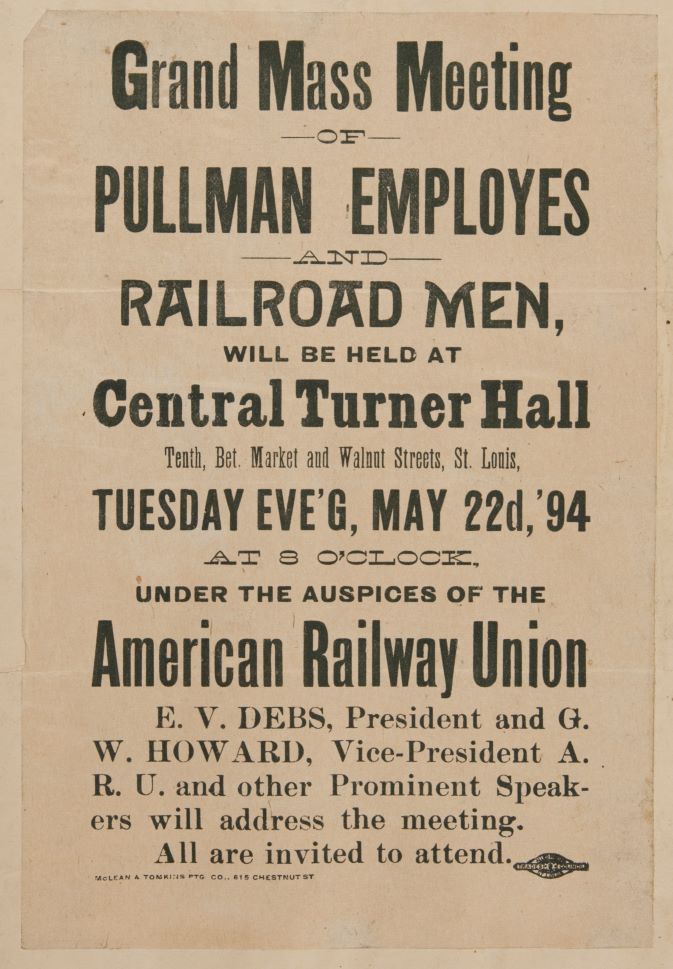

Debs shares memories of the American Railway Union and and its reverberations on the tenth anniversary of 1894’s Pullman Strike for ‘The Comrade.’

‘Stray Leaves from the Notebook of an Agitator’ by Eugene V. Debs from The Comrade. Vol. 3 No. 9. June, 1904.

Twenty-nine years ago on February 27th last I first joined a labor union. On that day my name was enrolled as a member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the very hour of my initiation I became an agitator It seemed to be the very thing I had been looking for — and I was ready for it. The whole current of my life was changed that day. I have a distinct recollection of the initiation and can still see the faces of the 21 “tallow pots” who made up the group of charter members, nearly all of whom, in the mutations of railroad life, have since gone over the range. A new purpose entered my life, a fresh force impelled me as I repeated the obligation to serve the “brotherhood,” and I left that meeting with a totally different and far loftier ambition than I had ever known before.

I had served my apprenticeship in the railroad shops and being the only “cub” at the time, knew what it was to have a dozen bosses at once and all the grievances I could carry without spilling.

Later, as a locomotive fireman, I learned something of the hardships of the rail in snow, sleet, and hail, of the ceaseless danger that lurks along the iron highway, the uncertainty of employment, scant wages, and the altogether trying lot of the workingman, so that from my very boyhood I was made to feel the wrongs of labor, and from the consciousness of these there also sprang the conviction that one day they would all be righted.

On the day I became a member of the union I was also elected one of its officers and for 21 years without a break, official position in some capacity claimed my service.

It was during this time that I organized the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakemen, now the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, and helped to organize the Switchmen’s Mutual Aid Association and a number of other organizations. The American Railway Union was the best of them all. It united all the workers in the service. That is why the railroad corporation declared it to be the worst of all.

For two years after the Pullman strike I was shadowed by railroad detectives, East, West, North, and South. The companies were determined to break up the union. We tried organizing in secret. It would not work. The spy could not be kept out. At Providence, Rhode Island, I organized at midnight in my bedroom at the hotel. The men had come from different directions, one at a time. The next morning they all were called into the office, paid off, and discharged. At New Decatur, Alabama, we had 111 members obligated in secret, one at a time. A member so admitted was not supposed to know who else belonged. One morning 18 of the more prominent of these were summoned to the office. The roll of the one hundred and eleven offenders was read off to them. For the first time they knew who their fellow members were. The officials had ferreted out the information and gave it to them from the company records. The 18 leaders were discharged outright. The remaining 88 were ordered to produce their final withdrawal cards from the American Railway Union within ten days. Hundreds of similar instances might be cited.

The railroad managers of the whole country were up in arms to annihilate the organization. From Maine to Arizona, from Florida to British Columbia, their bloodhounds were sniffing for the scent. At Williams, Arizona, two of them who had followed me from Albuquerque attempted to break into my room and in trying to force the door the bolt was sprung so the door could not be opened and I had to arouse the hotel attendants by a succession of yells, one of whom climbed over the transom armed with a screwdriver and removed the lock and bolt so as to release me in time to catch the four o’clock morning train for The Needles. The landlady was up and all was excitement. She knew the detectives and despised them. Her parting words were: “Watch out for the scoundrels or they’ll get you yet.” When the train pulled in, I got aboard so did the sleuths. One of them, the smaller of the two, who, as I observed, had a game leg, was quite friendly and offered me an “eye-opener” from a quart bottle. The other who was tall and had but one eye and the most murderous countenance I ever saw, which he kept shaded with the brim of an enormous slouch hat, had nothing to say. At The Needles an incident occurred which will make another story.

The railroad managers had a mortal dread of the ARU. They feared its very ghost. As the train stopped at Las Vegas on the return trip the editor of one of the papers got aboard for an interview. He imparted some quiet information he had obtained. Said he: “The wires here have been busy with your name. Not an employee will dare to come near you. The officials have prepared for any possible emergency The fact is they are quite alarmed. They fear they may have it all over again and even your shadow passing over the line would scare them.”

There was not the least bit of danger. The ARU was riddled with bullets and breathing its last as a railroad union.

The railroads were determined to stamp it out and forever. It was a dastardly conspiracy against vested interests! Its chief object was not to bury the dead, but to unite and emancipate the living.

But instead of stamping it out they stamped it into the living labor movement. The American Railroad Union became the Social Democracy. Thanks to the railroad companies for driving the union into politics, working class politics! Most of this power is still latent, but the start has been made and the rest are bound to come.

• • • • •

A little less than two years ago at Trinidad, Colorado, I was the guest of the railroad boys. I slept at their boarding house, ate at their table, and was once more one of them Two of them were known for their Damon and Pythias friendship. This is the story briefly told:

Jack had been a local leader in the ARU strike and when it was over was blacklisted and hunted with relentless fury. One night, far from his former home, ragged, half-starved, and shivering with cold he sat crouched in the corner of a boxcar loaded with machinery and rattling over the rough joints of a western road. Along toward morning he discovered that he was not the sole occupant of the car. His private car had evidently been invaded during the night. He hailed the intruder.

“Hello, there!” “Hello, back at you!”

The cut and fashion of their clothes and the general style of their outward appearance were near enough alike to mark them as twins.

“How’re you fixed?” “Not a sou.”

“Same here.” “Shake.”

Both were traveling under assumed names and both had good cause to be suspicious. But after a while their mutual misery dissolved the restraint. They warmed to each other, and they needed to, for they had hunger of the heart as well as the body.

“So you’re an old railroad man, eh?” “That’s right!”

“Anything to show for it?”

“Only this, partner, but hobo though I be, I wouldn’t take a farm for it.”

Saying this, Jack’s companion reached into his rags and pulled out a traveling card of the ARU that looked as far gone as its owner.

The two tramps embraced and vowed their mutual fidelity as the train reached its destination.

Then followed weeks of tramping, privation, and hunger pangs. The two became one, sleeping in the same straw-stack at night, covered by the same rags as they plodded wearily along, and sharing the same “handout” along the highway.

Finally Jack, through the influence of an old friend, struck a job. The “pie-card” he bought, his first investment, was for both. When payday came every cent was shared. jack and his friend once more had decent clothes and with Jack’s influence his partner soon had a job.

From that day these tramps have been as brothers. Their attachment for each other is beautiful, almost pathetic. The love they bear each other is holy love born of bruised and bleeding hearts crushed beneath the iron hoof of despotic power.

And thus are they who suffer for righteousness rewarded!

What Rockefeller has wealth enough to buy such a royal possession as the priceless heritage of these two tramps?

• • • • •

Not long ago I stopped at Salamanca, New York the first time in 26 years. My first visit was not for my health. I was put off there and it was two days before I managed to get out of town in the caboose of a freight train. I had the same experience several times before finally reaching Port Jervis, the Mecca of my pilgrimage, where Joshua Leach, the grand master of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, then had his headquarters.

My late visit was different. I was escorted to the opera house with the trade unions and many others in the cheering procession while the band was playing “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.”

My impression of Salamanca was altogether more favorable than that I received some five and twenty years ago when I started out in callow youth without scrip in my purse to save the world.

• • • • •

For just one night I was general manager of a great railroad, though I never received any salary for the service I rendered in that capacity.

The strike on the Great Northern, extending from St. Paul to the coast, was settled on the evening of May 1st, 1894. It was a complete victory for the ARU.

President James J. Hill and I had shaken hands and declared the hatchet buried. He said he was glad it was over and assured me that he had no feeling of resentment. As we stood chatting in his office he said: “By the way, Debs, you’ll have to be my general manager tonight, for the men won’t go to work except by your orders.” I said: All right, sir, I’ll guarantee that by morning the trains will all be running on schedule time.” He seemed to be nettled and I did not blame him when he said: “How about my wages? I too am an employee of the Great Northern Railway. And since everybody gets a raise, where do I come in?” He laughed heartily when I answered: “Join the American Railway Union and we’ll see that you get a square deal.”

And then I assumed the duties of general manager. The men all along the line were extremely suspicious. They had been betrayed before and were taking no chances. The chief operator sat at the keys while I dictated the orders. The messages were soon speeding over the wires. At some places there was no trouble. At others there was no little trouble to convince the men that there was no trickery about it and that the orders bearing my signature were genuine.

At last we had every point on the line started except one and the answer from there was: “The whole town is drunk and celebrating Will be ready for duty in the morning.” Nor did they cease celebrating until daylight and then all hands reported for duty.

When I left the Great Northern headquarters all the trains were moving the shops, yards, and offices were throbbing with activity, and everybody was happy.

My service as general manager of the Great Northern was entirely satisfactory to President Hill, as he assured me when I left there but I never applied for membership in the General Managers’ Association.

• • • • •

It was not long after this before President Hill and our own members wired me as to my interpretation of certain clauses of the agreement. It was evident that trouble was brewing again. I went to St. Paul on the first train. Our committee was promptly convened, but Mr. Hill could not be found. No one knew where he was. It struck me that delay was dangerous and that prompt action was necessary. We at once summoned Charles A. Pillsbury, the millionaire miller, since deceased, and a personal friend of Mr. Hill who had taken an active interest in the previous strike and settlement. Mr. Pillsbury and some of his associates came to the hall.

Mr. Pillsbury said if the agreement had been violated he did not know it. He did not know where Mr. Hill was and suggested that we would better wait patiently until he returned. He hoped we would not be rash and that there would be no trouble. When he took his seat I got up. “Mr. Pillsbury,” said I, “if Mr. Hill is not here, or if there is not someone here to act for him within 30 minutes, we will tie up the Great Northern from end to end.” The hall rang with applause. Within 15 minutes Mr. Hill was in the hall, we went into a back room and in about 30 minutes more everything was adjusted and for the second time the victory of the ARU was complete.

• • • • •

In the fall of 1896 I addressed a great political gathering at Duluth, Minnesota. The trade union banners were for the first time in a political procession. It was a red letter day. The crowd was immense. No hall was large enough and as it was too chilly for outdoors, arrangements were made to hold the meeting in the old streetcar stables. The roof was low, but there was ample room and this was what we needed. Just after I got started some man interrupted. Not understanding what he said I paused and asked him to repeat his remark. “I said you’re all right,” he exclaimed. Within a few feet of him towered a fellow who seemed seven feet tall. His eyes blazed daggers at the first party as he growled, “By God, you’d better!” The crowd cheered and there was not further interruption that night.

• • • • •

An introduction I once received is good for a heart laugh every time I recall the incident. There was intense prejudice against me and the young man who had been selected to introduce me to the audience concluded he would try to disarm it. The house was jammed. This was his first experience. He got along quite well till he forgot his lines. And then he closed somewhat abruptly after this fashion: “Mr. Debs is hated by some people because he has been in strikes. This is not right. It is the law of nature to defend yourself. Only a coward will refuse to stand up for his rights. Why, even a dog will growl if you try to deprive him of the bone he is gnawing, a cat will scratch in self-defense, a bee will sting to protect itself, a goat will butt you if you get in his way, while you all know what a jackass will do if you monkey with him. Ladies and gentlemen, this is Mr. Debs, who will now address you.”

He brought down the house and was immensely pleased with his first effort on the public platform.

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v03n09-jun-1904-The-Comrade.pdf