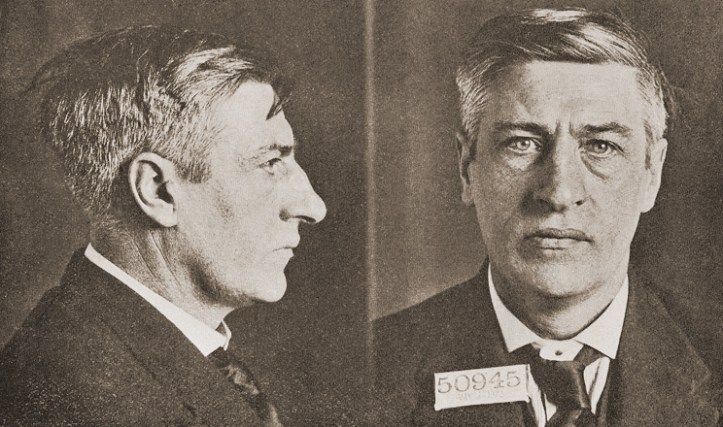

Jack Carney on the release from prison in the U.S. and return of James Larkin to Ireland with the Irish Revolution having intervened while he was away.

‘From Sing Sing to Dublin: Jim Larkin’ by Jack Carney from The Liberator. Vol. 7 No. 1 January, 1923.

THE workers of America were led to believe, some few months ago, that Ireland was upon the eve of establishing a republic. The impression in the United States has been that the Free State Government was backed up into the corner and its surrender was purely a matter of formality; that daily the Irish Republicans were scoring victory after victory with consequent routing of the Free State army. There are a few who still believe that such is the case but they are few, indeed. Their numbers are steadily decreasing as the murder machine of the Free State government goes on riding roughshod over the masses.

The stranger who arrived in Dublin last May with the feelings born of attendance at numerous meetings held in this country under the auspices of Irish Republicans was destined to undergo a certain disillusionment. Contrary to his expectations Dublin preserved its normal aspect, commonplace except that, where one formerly met British soldiers he now met Irish soldiers. The Grafton Street shops with show cases making their usual costly display were open and doing good business. The crowds were Circulating peacefully along O’Connell Street and along the banks of the Liffey. On Sunday afternoons one met dense crowds journeying to Phoenix Park to listen to the band of the Free State army. It is only around midnight that the stranger would meet with any interference. He had to submit to an occasional searching from a Free State patrol. This searching was now practically abolished.

Social life was normal. Movies, theatres and vaudeville houses were being well attended, likewise open-air boxing matches. Dublin did not appear to be the revolutionary furnace that we had been led to believe it.

Into this Dublin came Jim Larkin. Speculation was rife as to the manner of reception that would be accorded him upon his return. There were some who thought that he would be met by a few of the Old Guard. The officials of the Irish labor movement and labor party were worried. They did not know how Jim would be received, so they kept in the background. Previous to his landing in Ireland, Larkin had remained a weekend in London where he addressed the Executive Committee of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The greetings of Zinoviev were conveyed to him, together with a membership card in the Moscow Soviet. On the eve of May 1 Jim entered Dublin. After eight and a half years, during which time others had been privileged to lead the masses in tremendous struggles, the regard of the masses for Larkin was just as high as it ever had been. Dublin roared its welcome.’ The station was packed and thousands lined the surrounding thoroughfares. It was estimated by the capitalist press of Dublin that over twenty thousand had turned out to greet him.

Let there be no mistake about it. The masses of Dublin are with Larkin. He can call meetings at eight o’clock and find the masses still waiting for him along after midnight. On the anniversary of the execution of James Connolly over fifty thousand men and women stood in the pouring rain to hear him speak. He can command greater crowds than the Republicans or Free Staters. When the Republicans desire to raise funds they generally appeal to Larkin to be the main speaker, knowing that the crowd goes where Larkin goes.

Larkin went on a tour of the South of Ireland in an endeavor to bring about a cessation of hostilities between the Republicans and the Free Staters. He saw that continued war would end in the annihilation of the Republican forces and leave Ireland bereft of the flower of its race. Time alone will justify the soundness of his policy in this direction.

Many were surprised that the “stormy petrel” of Ireland should demand a cessation of hostilities between the Republicans and the Free State. They little knew the man. He saw how strong the Free Staters were. They had armored cars, plentiful supply of guns and ammunition, and the entire resources of the British Government behind them. The Republicans measured their man-power in hundreds, while the Free State had thousands. The Republicans has very few guns and very little chance of securing any more. More than fourteen thousand of their best fighters were in prison. A Republican victory was impossible. The Republicans had failed to understand that the readiness· to wait, the negative element in morale, is as important as the readiness to act, and ofttimes it is the harder virtue. They further failed to realize that the hearts of men cannot always be kept up by the flattering stimulus of always going forward, a state of mind that has caused many a commanding officer a serious embarrassment, notably in the case of the Dardanelles, even to making decisive strokes of strategy impossible. The Free State wanted to continue the fighting so that they could have a pretext for their autocratic legislation and at the same time continue their brutal policy of shooting down every Republican soldier they met. Certain ascetic tendencies among Republican leaders assisted the Free State in the partial carrying out of their murderous resolve. Acceptance of the advice put forth by Larkin would have found the Republicans in a much stronger position.

Prior to his tour through the South of Ireland, Larkin appeared before the Executive Committee of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, the most important union in Ireland, to tell them that he had decided to resign his position as general secretary, a position he had held continuously since the organization was first formed. For one whole afternoon the executive had pleaded with him to reconsider his decision. He finally consented to remain as general secretary, with the understanding that there be loyalty of each to the other.

Upon his return to Dublin he found that during his absence the executive committee of the union had drawn up and, with the assistance of the government, had hurriedly registered, a set of new rules under which Larkin and the rank and file will find themselves in a perpetual minority. The rules are so framed that the executive can count on about eighty delegates out of one hundred and twenty or so at every national convention. Members of the largest branch, No.1 in Dublin, some eleven thousand strong, protested and suspended those members of the executive who belonged to this particular branch. The suspended members of the executive knew where to go for assistance. They rushed to court and there the union issue lies, awaiting the verdict of the court. Some peculiar things have happened in Ireland during the past years, which Larkin was anxious to investigate. The new rules were drawn up to prevent such an investigation. The executive thought that, with the strike of the farm laborers and the coming offensive of the Dublin employers, Larkin would be afraid to act. They little knew the man. Larkin at no time will lend himself to any action that will injure the membership of the union, but he realized that a corrupt leadership is the worst asset in any struggle, that unless this leadership was exposed the masses would be betrayed.

Larkin is anxious to solidify the forces of organized labor. He realizes that without a solidified labor movement other movements are of little consequence. The Irish Transport Union is no more a solidified body than is the American Federation of Labor. Small unions in Ireland have received similar treatment to that accorded small unions by the big international unions in America. Irish labor leaders no more than American labor leaders want an organized labor movement. They want an organized officialdom, but not an organized rank and file. The employing class is continually pointing out in its press that all the labor leaders are “sane and sensible but this man Larkin.”

It is Larkin’s program to organize the rank and file in such a manner that they will develop the movement and produce a leadership that will lead the masses into action.

Many in America have felt that Larkin should not have attacked the Irish Labor Party, especially on the approach of the elections. It is interesting to note that it is reported that Thomas Johnson, leader of the Irish Labor Party, is to be made Minister of Commerce in the Free State cabinet. “It is generally conceded that he (Mr. Johnson) will continue as leader of his party and of the Opposition,” writes the organ of the Irish employers, the “Irish Independent”. When the Minister of Defense, Richard Mulcahy, was at a loss to explain the reason for the many executions, he could generally rely upon the leader of the Labor Party to come to his rescue. For instance, “Did not these executions arise out of military necessity?” asked the leader of the Labor Party. “As has been suggested by the leader of the Opposition, these executions were due to military necessity”, the Minister of Defense would reply. Catha O’Shannon, another prominent member of the Labor Party, had the gall to state in the Dail that he could see justification for a flogging law being passed in Ireland. Another member, Sean Lyons declared that Cosgrave was the greatest man born in Ireland during the last seven hundred years. The Irish Labor Party draws its inspiration from the British Labor Party. The only difference between the two being that occasionally, due to the presence of militant scotch- men, the British Labor Party does make a fight. If the Irish Labor Party had refused to sit in the Dail they would have stripped the Free State of its mask of so-called constitutionalism and exposed it for what, it is, a brutal military junta.

The Free State supporters declare that the Free State is the next step towards a Republic. They remind one of an incident that took place at a Lloyd George meeting. “We shall not rest content until we have secured the fruits of victory,” declared Lloyd George. “Yes, we have no bananas,” interjected a member of the unemployed. The Republicans center their objections around the oath to King George. If the oath were withdrawn, they state, they would sit in the Dail. The Free State accepts the position of being within the British Empire. The Republicans prefer to be part of an association of nations. To overcome the oath the Republicans are prepared to pay a monetary tribute to King George. There is no fundamental difference between the official positions of the Free State and Republican parties. Yet brave men and women have died heroic deaths and just as brave men and women risk their lives in hunger strikes. If heroism and courage are the only essentials to success, then the Republicans succeed. Unfortunately these are not the only essentials.

Both sides, Free State and Republican, have deliberately ignored the claims of Labor. Both of them are content to play to Labor for support but refuse to accord to Labor any consideration as an independent force. During the Black and Tan regime, under a Republican cabinet, with the “revolutionary” Countess Markieviecz as Minister of Labor, pickets were ordered off the streets of Dublin. When negotiations were opened up with Lloyd George, labor was ignored. When the Free State government was formed the Free Staters did not even make any attempt to corrupt Labor with a seat in its cabinet. When peace overtures were made, the Republicans, also, felt that it was better to have an avowed reactionary such as Senator Douglas to act as mediator.

The Free Staters draw their power from the employing class, the latter lending them their undivided support. It is true that the employers elected their own candidates at the last election. But in a contest between Free Staters and Republicans they are Free Staters. The middle-class is Free State. They are not a large factor in the political situation. In addition to these, the wealthy farmers are· supporters of the Free State. They have their own party, the Farmers’ Party, but they are supporters of the government in cases of emergency. Supporting the Republicans are the small farmers. They want land but they do not want a workers’ republic. It is here with the main support of the Republicans lie. Then we have the Irish Labor Party. It, also, is Free State. It occasionally makes a “fight” in the Dail, but it more the exception than the rule.

Outside of all these political forces stands Larkin. He is out to weld the farm and industrial workers into one united working class. Opposing him are all those forces which support the Free State, because Larkin has made it quite clear that he is Republican, not republican in the sense that many understand it. Larkin desires a workers’ republic. He realizes that he has a greater task than any he has ever attempted. His work cannot be judged at this moment. He is now engaged in clearing away the obstacles within the labor movement that seek to prevent the unification of the forces of Irish labor. In 1913, by means of the Dublin strike, he succeeded in focusing the attention of Ireland upon the terrible poverty that degraded its working class. Men like “AE”, Patrick Pearse, James Stephen, Thomas McDonagh, Joseph Plunkett and W.B. Yeats found themselves brought to a point where they shared each other’s views in the necessity of supporting the Dublin strike. There are some who, today, believe that under the leadership of Larkin the masses of Ireland will again be welded into a fighting force that will make the next struggle in Ireland so decisive in character that there will be no question as to what it is all about. Larkin, today, finds himself faced with a situation that many would shrink from. He realizes that not alone must one engage in the task of organizing the masses. Ways and means must also be devised for reconstructing the nation. He is not content to dabble in minor schemes. He is out to bring an understanding between Soviet Russia and Ireland. When Krassin and Lord Curzon were engaged in a dispute that might have meant a rupture of trade relations it was Larkin who had the foresight to inform Krassin “if London rejects you come to Dublin.” This is another story. The Communists of America need have no worry as to where Larkin stands. The Communist International realizes that Larkin stands for Communism. Some Communists may not understand his methods, but men like Zinoviev, Radek and Buhkarin have pledged him their support. Backing the Free State stands the British Labor Party and Amsterdam. Backing Larkin’s movement stand the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Communist International. Those interested in the success of Larkin should know that he may be found at 17 Gardiners Place, Dublin, Ireland.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1924/01/v7n01-w69-jan-1924-liberator.pdf