Of obvious interest and importance, at the time of writing Rakovsky was Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

‘Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine: Their Mutual Relations and Destinies.’ by Christian Rakovsky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 24. December 11, 1920.

THE socialistic revolution not only transforms the internal economic and political structure of states, but also fundamentally alters the relations between them. The relations between the Soviet states are essentially different from the relations between bourgeois states. The bourgeois statehood is distinguished from the proletarian statehood even in its rudimentary principles. The proletarian statehood does not fit into any of the classifications that have been set up by the political economists of the old world.

The general presupposition of all forms of administrations — the aristocratic, the democratic, the absolute monarchy, the constitutional monarchy, the republic, etc. — was the exclusiveness, the segregation, of the state organism. The most democratic of the democratic republics put their own citizens into a sort of opposition to foreigners. In the most democratic republic the foreigners are not admitted to the political life of the country. The political life was a privilege of the national classes concerned, or at best, of the citizens of the state in question. In the constitution of the Soviet nations on the other hand, both of Russia and Ukraine, one fundamental principle is precisely the abolition of all racial privileges; thus for example, paragraph 20, section C of the Constitution of the Ukraine Socialistic Republic states: “Foreigners belonging to the working class or the peasants actually working as such, enjoy the right of suffrage”. Such a constitutional provision is completely incomprehensible to the bourgeois jurist who customarily begins by assuming the opposition of his own state towards other states, of its citizens to foreigners. But this provision is a logical result of the most fundamental quality of the proletariat.

What is the main difference between the proletarian and the bourgeois state in their different economic bases, which are entirely exclusive.

The bourgeois state as well as the forms of state organs which preceded it, is based on the principle of private property in land and in the means of production. The whole so-called bourgeois law, regulating relations between the private owners, is based on this principle. The state as a whole, with all its institutions, its military, administrative and economic organisms — together with its church — likewise constituted such property, but of course not the property of the possessors of the means of labor, but the property of the entire possessing class, of the bourgeois landed proprietors or slave holding classes. The object of each private owner is the extension and enlargement of his holding. Competition is a means for obtaining this goal. The outcome of the law of competition is destruction or at best subjection of the less wealthy and the less skilled owners to those owners who have greater means, greater capital, and greater ability. The same law controls also the development of the bourgeois states. They constitute precisely such organisms, competing among themselves, and the outcome of this competition is the same, — the complete destruction of the weak states or at best their subjection to the strong states. The principle of bourgeois statehood is expressed precisely in the creation of these individual mutually hostile national states. Between these states, there may be concluded commercial treaties, postal, telegraph and railroad agreements; as the international situation varies, there may be defensive and offensive alliances between them, but such arrangements are temporary, fortuitous and incomplete in character. Such arrangements cannot eliminate the peculiar and profound antagonism existing between these states and in the entire capitalist order of society. As soon as the danger uniting various countries, or their temporary coincidences of self-interest are passed, struggle and hatred once more blaze up between them with increased force, for such conflict grows out of their very nature. Particularly characteristic in this connection is the history of the coalition of the entente states and of their allies before and after the imperialistic war. The ideology of bourgeois statehood is nationalism. Diplomatic intrigues, “spying” of every kind, mutual deception, are the regular devices of the bourgeois power.

When Marx, in the first manifesto of the International in designating the foreign policy of the capitalist states, held up to them by contrast a policy that should be based on the laws of human morality, he of course did not mean that the socialists in bourgeois society should support the Christian morality as opposed to this policy of the state: “Do not do unto others what you would not have them do unto you.” He called the attention of the proletariat to the fact that only through the victory of a proletarian revolution could the conditions for honest and straightforward relations between all nations be brought about. As opposed to the bourgeois statehood the proletarian statehood, which rejects private property as a means of production, simultaneously defies private property as an attribute of the state itself. In the socialistic state the normalizing principle is not the interest of the private exploiter, but the interest of the entire working-class. The boundaries separating socialistic states will no longer have a political character, but will be transformed into simple administrative limits. Likewise there will disappear the frontiers between the individual private productions which are regulated only by the law of competition. Instead of the chaotic, capitalistic economy, in which the most voluminous production of manufactures and the most intense exploitation of the worker alternate with industrial crisis and unemployment, there will be an oganized nationalized production, rationally developed according to the general needs on a nation-wide plan, and not only on a national scale but also on an international scale. The tendency of socialistic revolution is political and economic centralization, provisionally taking the form of an international federation. Of course, the creation of this federation cannot be effected by a stroke of the pen, but is the result of a more or less extended process of elimination of particularism, provincialism, democratic and national bourgeois prejudices, which will result from mutual acquaintance and from mutual adaptation.

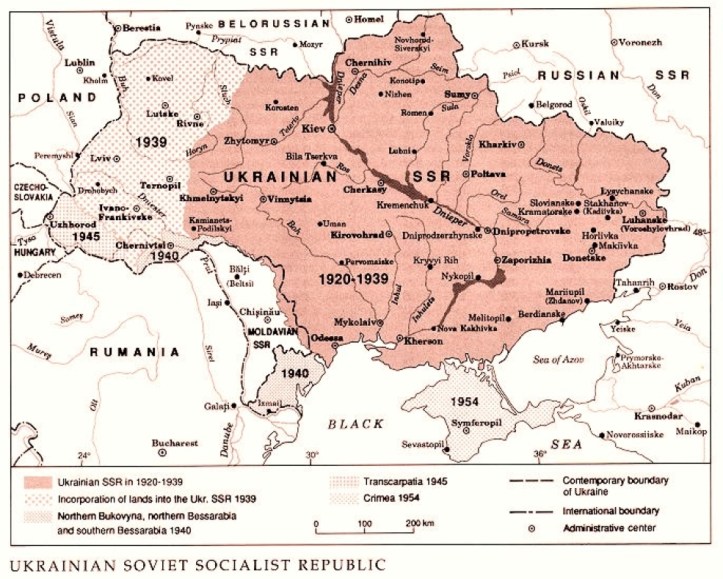

The above principles, which were already announced by the first workers’ International, were naturally the cases for the relations between the already existing Soviet republics, particularly between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine. From the first moment of the joint existence of these republics, Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine began laying the bases for economic and political relations along federative lines. Although during this phase, which extended up to June, 1919, both republics had independent commissariats for all branches of their national affairs, there was nevertheless already a connection and a joint plan of work existing between these commissariats. In the course of time these two republics found their organized expression in the creation of common central organs. In June, 1919, the Central Executive Committee of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic adopted a resolution on the necessity of uniting a number of the commissariats of the two republics, namely, the Commissariats for Army and Navy, Transportation, Finances, Labor, Postal and Telegraph, and the Supreme Councils of National Economy. This resolution was ratified by the Central Executive Committee of the Russian Soviet Republic, and in 1920 the First Congress of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Soviets of Ukraine also approved, on its part, the decision of both Central Executive Committees in a modified resolution. A precise constitution of the federative organs, that is, of the organs uniting the Ukrainian Commissariats, has not yet been worked out. The Central Executive Committee of Soviet Russia, in its February session, proposed a list of members of commissions which were to occupy themselves with the elaboration of the federative constitution. But because of the fact that the responsible members of these commissions were assigned to military and political duties outside of Moscow, it has not been found possible to undertake the discharge of this task, and the federative relations are still regulated for each case separately, by immediate agreements between the two republics.

Such an agreement was made in January last year, concerning military affairs. In uniting the army apparatus, this union also provided for a creation, in the immediate future, of separate cadres for the Ukrainian Red Regiments, with the Ukrainian language used in commands. For this purpose, the creation of a school for Red Ukrainian commanders was provided, and this has been already realized. In Kharkov the founding of a central school for Red commanders has been already undertaken. Already in this agreement the creation of a military section in the Council of People’s Commissars of Ukraine provided for the purpose of maintaining permanent liaison with the military and administrative apparatus in Ukraine, which is immediately under the revolutionary military council of the republic, which is simultaneously a revolutionary military council of the federation.

There still remain separate, in the two republics, the People’s Commissariats for Agriculture, Education, Internal Affairs, Social Welfare, Popular Health, Provisions, Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection, as well as the Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution. The Ukrainian Council of People’s Commissars at present constitute the People’s Commissars of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, and the authorized plenipotentiaries of the United Commissariats. The latter have the same suffrage right as the Ukrainian commissars.

This system of federative relations may not be considered as either complete or perfect. We did not approach the question of the federative relations in a dogmatic spirit, for we were never of the opinion that national relations, particularly the relations between Soviet republics, could be regulated on the bases of abstract provisions. The federative constitution of the Soviet republics was dictated by necessity itself, and fully considered the acquired national experience. The particular relations in which Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine stood toward each other considerably facilitated the task of a swift creation of close federative relations between them. The proletariats of the two states were, historically, closely connected through their past, through their common struggle against Russian Czarism. Besides, Ukraine and Great Russia were united by a common economic life. After the November Revolution, Soviet Russia became the national support for the struggle of the workers and peasants of Ukraine against the Central Rada, against the Austrian-German occupation, against the Hetman authority, against the Denikin government, and now, finally, against the Poles. The Ukrainian workers’ and peasants’ revolution naturally had to guide itself by Soviet Russia, which was the only Soviet center. The Communist movements in Ukraine and in Russia “were already historically connected through their common past. The party of the Bolsheviki organized the working class with- in the entire former Russian Empire. In Ukraine, this task was made easier by the fact that the city proletariat in that region is, to an overwhelming extent, of Russian origin.

But the various Ukrainian petit bourgeois “socialist” parties, which put the national element in- to the foreground and sacrificed the social revolution of the working class, evinced a tendency from the very earliest days of the revolution, already in February, 1917, to split the working class in Ukraine, to put up the Ukrainian workers, and particularly the Ukrainian peasants, in opposition to Russia. During the Provisional Government of Kerensky, they concealed their national policy be- hind the slogans of federalism, for they beheld in this government a petit bourgeois government very much like their own, a policy related to their own. They were led to sacrifice even their national policy.

After the November Revolution, these nationalistic parties openly set their course toward a complete separation of the Ukrainian working-class and peasantry from the Russian working-class and peasantry. In the peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk, they definitely entered the camp of the Austrian-German nationalists. From this moment on, the Ukrainian Social-Nationalists adhered definitely to the western orientation, that is, the orientation of imperialistic counter-revolution. For two and a half years Ukraine was a theater of civil war, not only between the workers and peasants, on the one hand, and the landed proprietors and capitalists, on the other, but also between the class-conscious portions of the working class and the peasantry and the unawakened elements, which followed in the wake of the petit bourgeois Ukrainian National-Socialist parties, and actually supported the Russian and the international counter-revolution. We may say that the civil war in Ukraine has now in both these phases arrived at its conclusion; the proletariat has now finally defeated not only the White Guard counter-revolution, but also the petit bourgeois nationalist counter- revolution. The Ukrainian national socialistic parties have fallen to pieces. Their best elements have already entered the Communist Party (Bolsheviki) of Ukraine, which is at this moment the only political representative of the proletariat and of the revolutionary peasantry of that country.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n24-dec-11-1920-soviet-russia.pdf