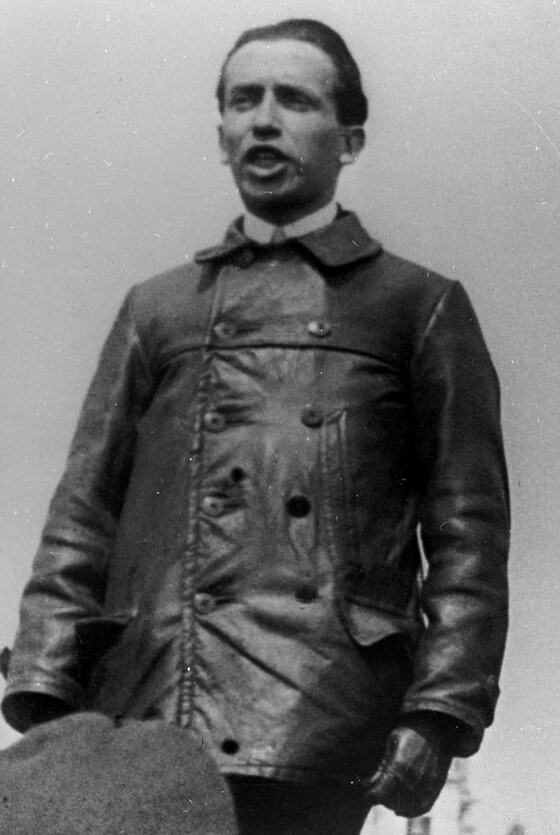

‘Tibor Szamuely: A Hero of the Revolution’ by Nikolai Bukharin from The Toiler. No. 129. July 23, 1920.

Every proletarian must and will familiarize himself with this name.

After the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, it was found on the frontier that one of its prominent leaders had met his end. We do not know precisely under what conditions such a valuable life for the working class ceased to exist. The official news was sounded that comrade Szamuely, being arrested by the gendarmes of Renner and the “Second Internationale,” who just yesterday were gendarmes of Karl of Hapsburg, had ended his life by committing suicide shooting himself. Possibly it happened so.

Comrade Szamuely was a proud character of iron will; the probability of falling alive in the hands of his enemies, may have drawn him into this despair. He probably could not conceive the surrender of his revolutionary sword to his foes, but preferred death to imprisonment. Another thing is possible. Are the gendarmes of Renner better than the gendarmes of Noske? Are Seitz and Bauer better than Schidemann and Ebert? And if the German hangmen, who, motivated by an “attempt to escape” murdered Karl Liebknceht and Rosa Luxemburg, the same could be accomplished by the Austrian hangmen against comrade Szamuely.

The Hungarian proletariat can be proud of this individual. We understand the madness and the anger that the Hungarian bourgeoisie had against our comrade. An unbending will, a rare coolbloodedness, a brilliant and sharp pen and unbreakable energy, those were the outstanding characteristic of comrade Szamuely.

He acquired his revolutionary lesson, as did Bela Kuhn, with us in Russia, and here it was that the writer of these lines made his acquaintance. Before that Szamuely was the editor of the central organ of the Hungarian socialists “Nepszava”. During the war in which he experienced much, as an officer, he was captured. Here he lived tinder the most unbearable conditions in Manchuria and Siberia. Frequently he was forced to work in the mines in mud and water knee deep. Hard sickness he suffered. He once attempted to escape, but on the Swedish frontier was rearrested by the Czar’s gendarmes. At last the revolution set him free.

Since then Szamuely, like a young eagle exercised his wings. There are very few who so self-denyingly devote themselves to the cause that put the historical strata in motion; like a real revolutionist he was imbued with the art of a revolutionist. He was ready for every deed- even the unpleasant and unattractive in character, the greatest and the smallest alike. With similar enthusiasm actively engaged in study class work; being the editor of the newspaper he, with that weapon combatted the outbreak of the counterrevolution, he wrote pamphlets, he worked in extraordinary committees, spoke at meetings or drew the order of the day for other comrades. At any moment he was ready to let his “Mauser” talk from which he never parted. A man of unusual courage, Szamuely always was on the lookout.

Generally necrologies are not free from exaggeration. That does not pertain to Szamuely, in relation to him it cannot be exaggerated. I am writing these lines, and imagine before me lovely and wise eyes of my comrade, from these eyes a tired glimpse with sarcastic smile flawing steadily, tired, nervous, but energetic face. Comrade Szamuely rarely slept more than from four to five hours, the rest of his life was devoted to the revolution.

Many people have I seen, revolutionists of all countries. But rarely have I found so confidential and devoted comrades as Szamuely. All his life was a beautiful example of revolutionary chivalry. Szamuely died in his youth. There is no doubt that his virtues would develop more broadly. But even what he gave the proletariat in his early years, is unforgettable. Among the other martyrs his figure will be an outstanding one between the two historical epochs as a symbol in the struggle and Communism.

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/129-jul-23-1920-Toiler-LOC.pdf