‘The Hotel Workers Revolt’ by Jeremiah Kelly from New Masses. Vol. 10 No. 6. February 6, 1934.

THERE was a roar of voices in strike headquarters, up the narrow flight of stairs. As you went in a bulletin board met you, on which were chalked the hours when the employees of various big hotels were having their shop meetings: Roosevelt to meet at 5; St. Moritz, 6, all the elegant hotels of New York were having meetings.

It was hard to get through the crowd. There was that hopeful excitement in the air that occurs when a mass of workers have streamed out on strike, and have at last, by striking, made vocal long suffered grievances. On one side was a big hall, on the other the office. A string of people were lined up at three windows. Cooks, waiters, hotel workers, taking out their membership cards.

“We’ve taken in 1,000 memberships today,” someone told me.

It was getting to be near five o’clock, the moment when, if there was no response from the employers, the general strike was to be called. There was a babel of many languages. One heard Italian; French, German. The suave waiters of the fashionable hotels were off duty. Their suaveness was laid aside. Their deference had been taken off with their aprons when they went on strike-tired of seeing the luxury of New York pass continually before their eyes, while· they worked long hours for small wages, sometimes for no wages at all, sometimes paying for their jobs and getting only what tips they might.

There had been a dramatic scene in the Waldorf-Astoria two days before. For many years Andre Fournigalt had been employed as sous-chef at the Waldorf-Astoria. For months past he has been an active member in the Hotel union. This is the real reason he was fired. The alleged reason is his services “were no longer satisfactory.”

The firing of the sous-chef was a signal for long awaited revolt.

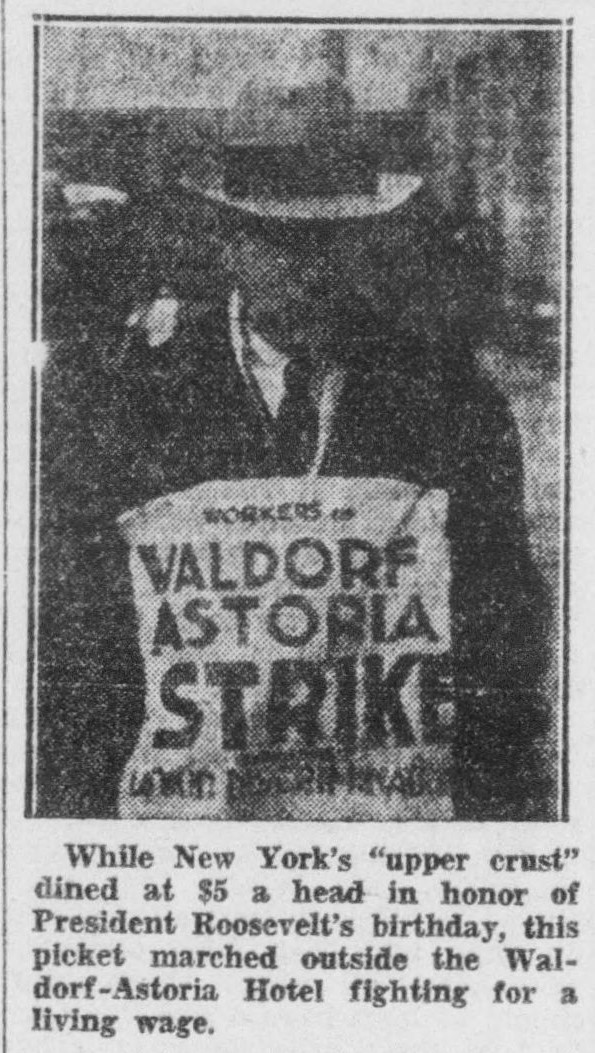

Suddenly at 7 p.m., the peak of the dining hour, waiters vanished from the Sert room with its huge paintings; there were no waiters in the other restaurants of the Waldorf. Meantime, in the kitchen, the cooks and the helpers were standing with their arms folded, confronting the great Oscar and the great Mr. Boomer. The dining rooms folded up, the patrons left, the lights went out.

Half cooked dishes sizzled on stoves. Dishes ready to serve began to cool, with no one to serve them. Bus-boys and waiters trooped from dining rooms to join the quiescent cooks. Groups of determined men stood around the kitchen, waiting. There had been food prepared for three big dinners. Beside the head chefs and the waiter-captains there was no one left who would serve them.

Oscar Tchirsky went up to the kitchen on the eighteenth floor, where the cooks, the busboys and the waiters were assembled.

“Come on,” he cried. “Three big dinners have to be served. Who’s going to work? Anyone willing to work step over to my side. The rest get out.”

A handful stepped over to Oscar’s side of the room. Two policemen came stalking in. The rest of the workers–the whole service staff 600 strong- quietly and firmly withdrew. The three great dinners were served by hurriedly summoned scabs and some of the head people.

Meantime, other hotels had walked out. Waiters and other hotel help flocked in such numbers to headquarters that the meeting hall could not contain them. They extended clear out into the street. They blocked traffic. Other meeting halls had to be hired.

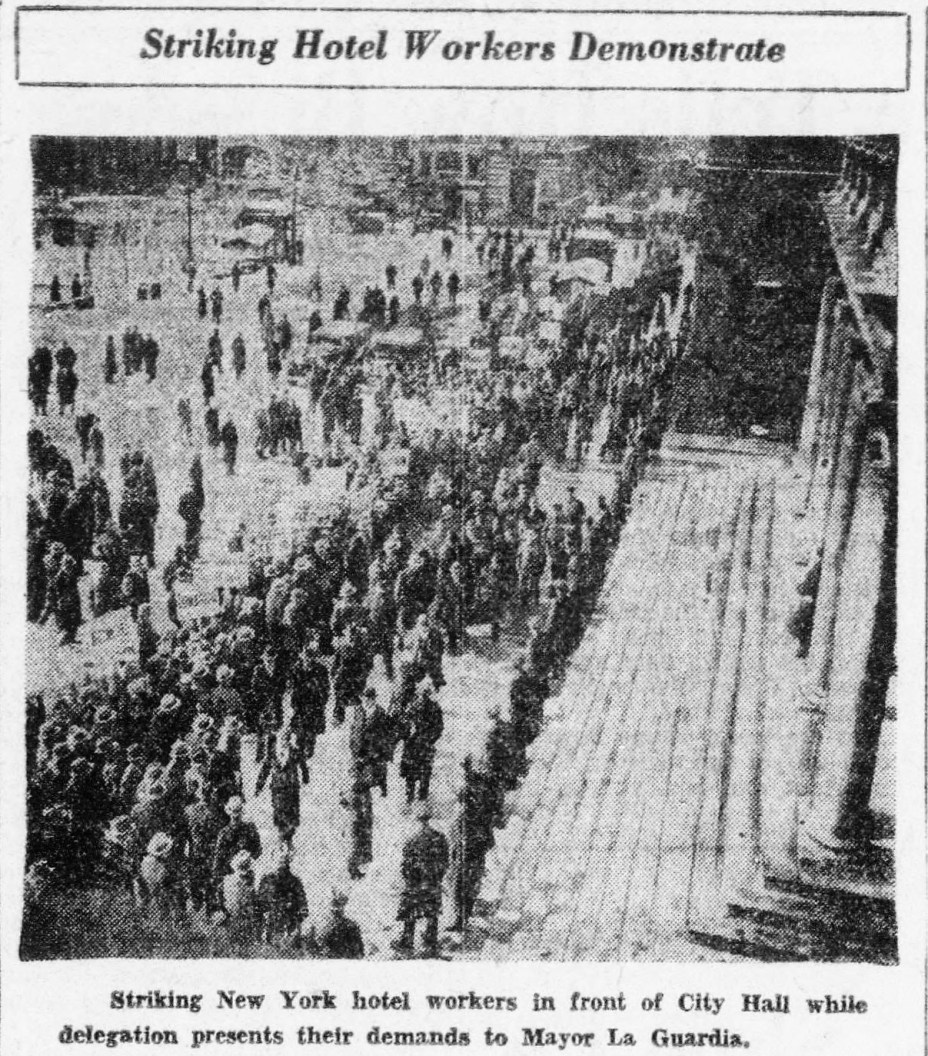

During the meetings three thousand members of the union waved their hands in the air in a viva voce ballot. They acclaimed the general strike resolution with shouts.

The demands of the strikers were: 1, recognition of the union; 2, a 40-hour week; 3, a $20 wage, and 4, improved conditions of labor.

The A.F. of L. leaders played the part of strike breakers. “As usual,” one of the cooks’ helpers remarked grimly. It was engaged in swearing out injunctions against the striking hotel workers. They had applied for a court order to restrain the strikers from picketing.

The food workers explained that the Geneva Association, an old-line restaurant and hotel employees’ benevolent association, acting together with others–including chefs, headwaiters and bell captains–were trying to break the strike. These old-line “benevolent societies” are affiliated in a federation of Hotel and Restaurant Guilds.

“These are no better than a company union,” the workers will tell you. “Look at this–” and they showed a telegram which had been sent to a member of the union by the Federation of Hotel Guilds: “Urgently request you report to Waldorf immediately. Attempted strike has failed and your job is at stake. Full protection.”

The answer of the strikers to this and other strike breaking maneuvers was a vigorous demonstration of 200 marchers against the Geneva Association’s quarters.

This was on Thursday. On Friday as five o’clock approached the feeling of tenseness grew in the strike headquarters. Here as one chatted with the members one could learn the grievances back of the general strike resolution. One could learn how wages had actually been reduced since the N.R.A. had come into effect. The kitchen maids’ $13 minimum had remained, but other categories of workers had been reduced. Kitchen forces had been lessened with increased hours. One learned of the various grafts in the getting of jobs the notorious Chef’s Club, for instance, to which other members had to pay tribute or lose their jobs; the phoney collections taken for alleged “benevolent” purposes; long hours, passed in ill-ventilated subterranean kitchens, these abuses piled one on top of another. The code had only sharpened the workers’ resistance, for of all the bad codes the Restaurant and Hotel codes are among the worst.

Now it was close to five, when the employers’ answer was to be expected. Excitement grew; more people came in, more cards were taken out. Someone came through shouting:

“Everybody in the big hall I Everybody in the big hall, please!” And there was a surge of the crowd into the big hall. The chairs were all taken. Workers crowded the back of the hall. Kitchen helpers and chefs mingled with experienced waiters from the greatest hotels in New York. There were few women, and these were received with greetings.

“They’ll come later; they must come,” one of the French waiters said to me. An organizer addressed the meeting.

“This is no time for a speech,” he said. “No answer has come. The general strike is declared!” A buzz of excitement greeted this.

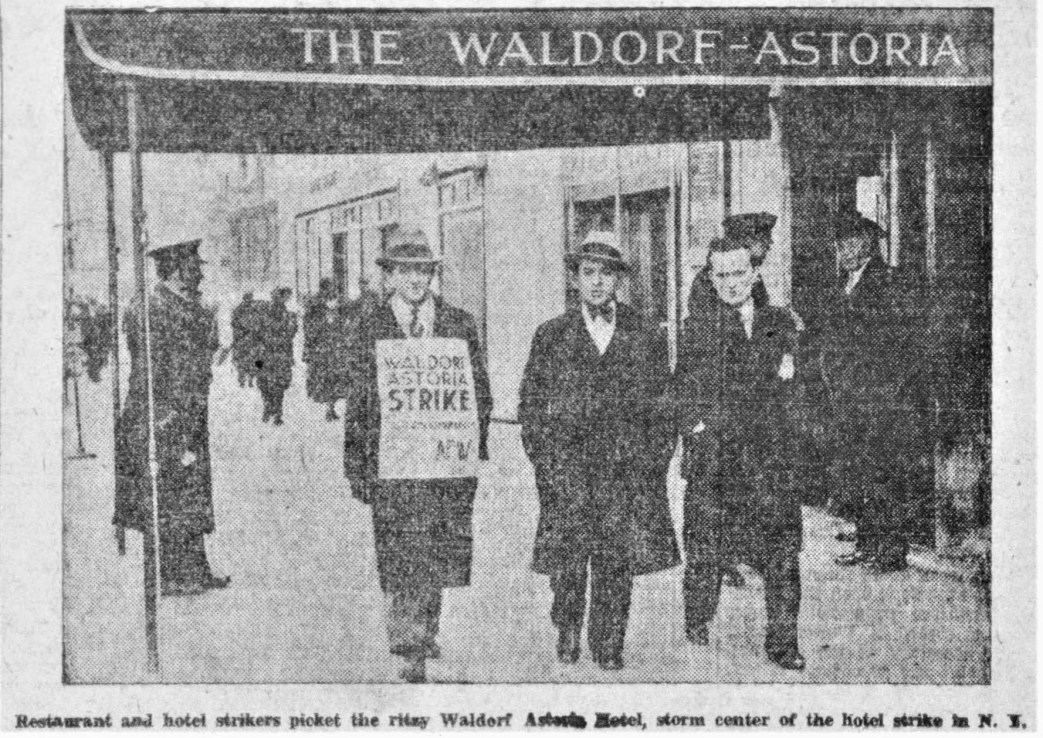

The picketing hotel workers encircled the huge Waldorf-Astoria, through whose vasty spaces I walked for the first time. It was a place hard to make out, and then its evident ancestry came to me. Undoubtedly it was the child of the Grand Central Station and the Ile de France. Not a hotel, exactly; rather a happy hunting ground for such persons as the Mdivanis and the spurious Mike Romanoff- who, in point of fact, at that moment came in, making his way past the many dicks who stood around watching the guests.

That the strike hadn’t spread to the other departments of the Waldorf was obvious. It has, however, at this writing, spread to include forty-one hotels in its scope.

The hotel employers and the press of course minimize the movement. At this writing it is too early to say whether the primary objects of the strike will be achieved. It is certain to me it is the most potent movement of the hotel workers since 1918.

But the hotel owners use every means at their disposal to smash the strike. The following note on the letterhead of the Hotel Montclair is illuminating. Dated Jan. 26, it was addressed to a Mr. J. Dictrow, of the Academy Employment Agency at 1251 Sixth Avenue.

“Gentlemen: Permit me to thank you for the service you rendered me in connection with breaking the recent strike of the restaurant and kitchen forces in this hotel. You did a good job- helped us out considerably. If at any time I can help you, in any way, I shall be glad to do what I can to assist.”

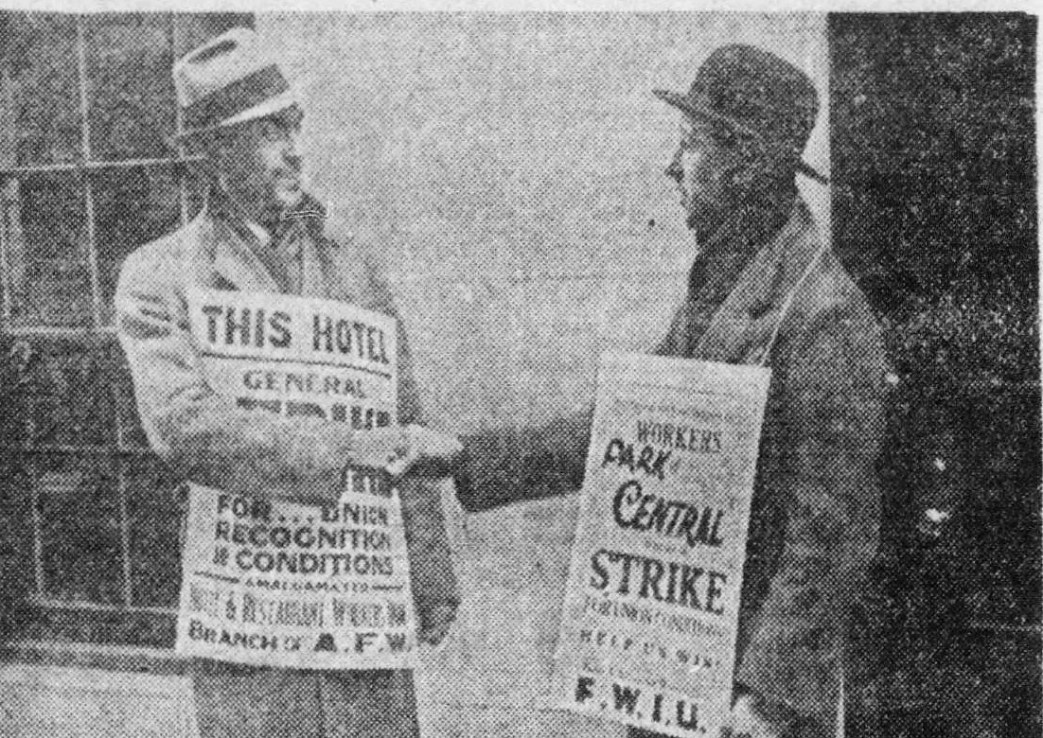

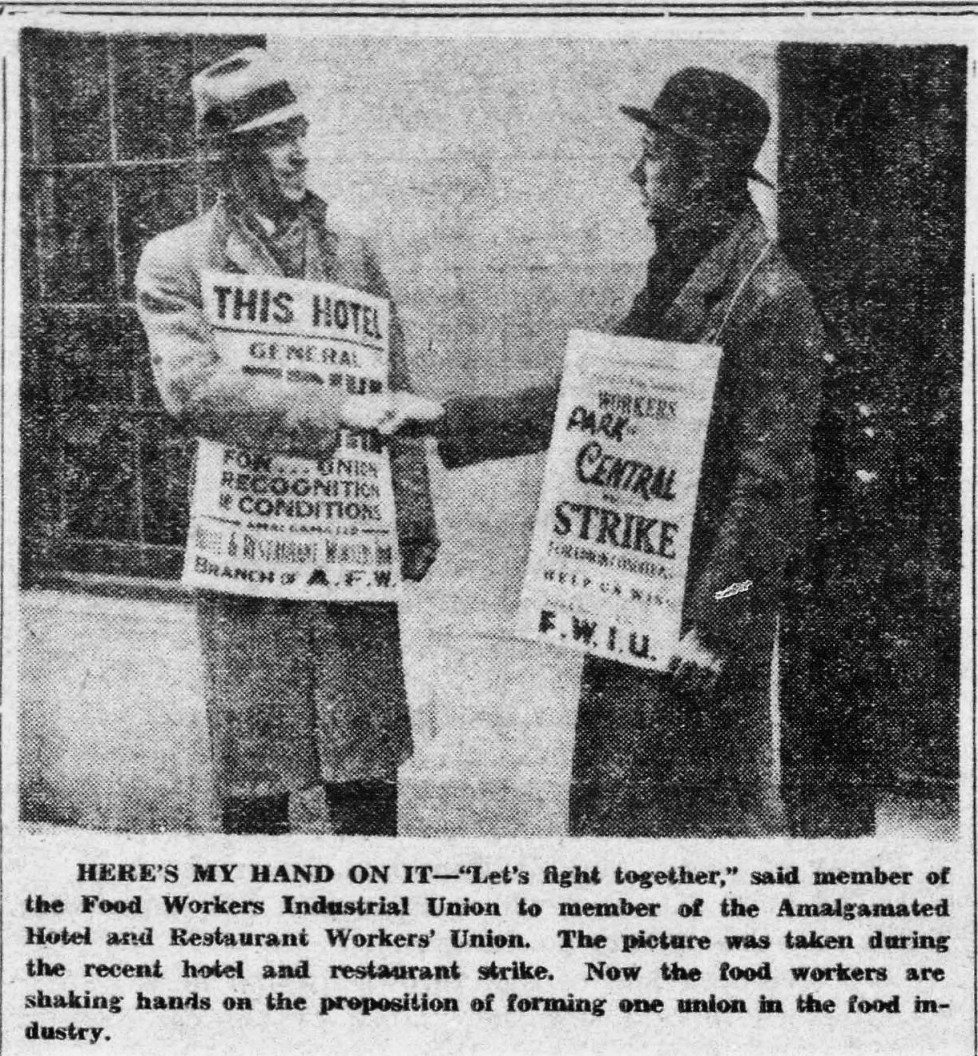

Open strikebreaking is one danger. Another and a greater danger is the refusal of the leaders of the Amalgamated Hotel and Restaurant Workers Union to accept the proffers of a united front with other organizations. This is the gravest blow to the possibilities of success. The day before the general strike was called, a committee of fifty strikers, chosen at a mass meeting of the Hotel and Restaurant Workers, Local 119 of the Food Workers Industrial Union, marched to the Amalgamated headquarters and called for unity. B. J. Fields, organizer for the Amalgamated, delivered a diatribe against Local 119, whose members he characterized as “splitters.” Before the committee could reply, the lights were switched off, and Fields abandoned the hall.

Ben Gitlow, who some years ago deserted the Communist ranks and is now one of the leaders of the Amalgamated, raised the cry “Communists!” in the best Hamilton Fish style, stating that the latter were “trying to capture” the strike. No association with the “Communists at the bead of the Food Workers Industrial Union!” he cried, for that would “cause public opinion to go against us, and the N.R.A. would be against us.”

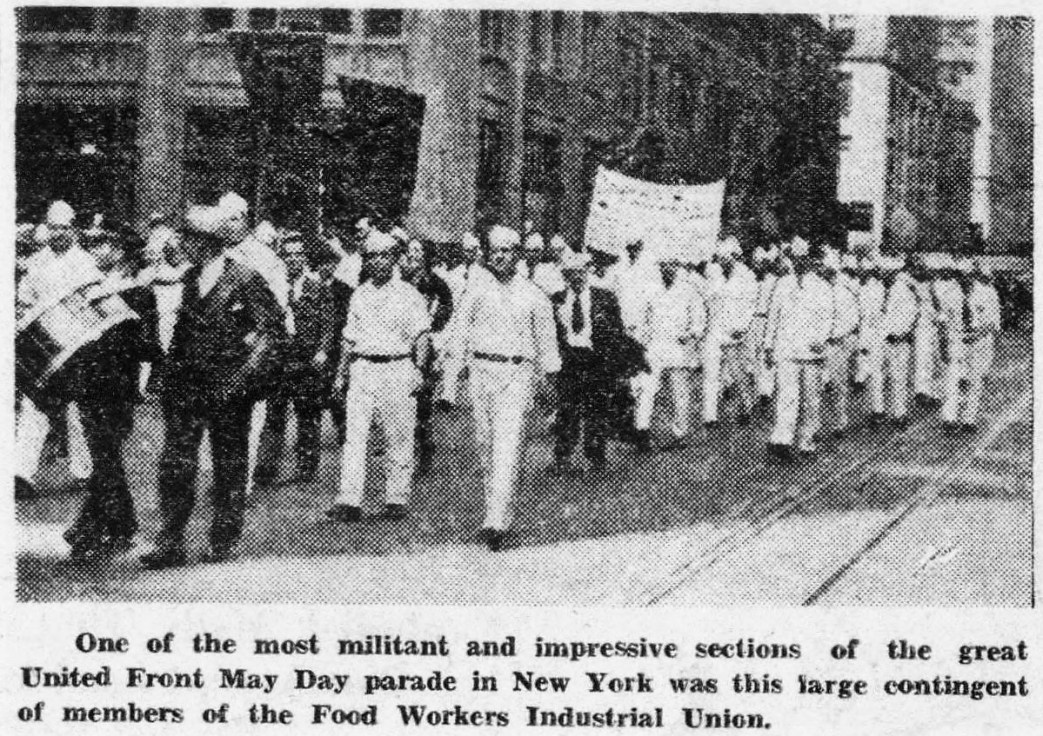

The F.W.I.U. has, since the beginning of the strike, hammered away for a united front. “Only unity can win the general strike,” say their leaflets, handed out in thousands before the city’s hotels. The strikers of Hotel New Yorker and the General Strike Committee of the Hotel and Restaurant Workers Union met and a decision was reached to join forces with the Amalgamated. They declared the necessity to “spread the strike to all hotels and to bring out the workers in all departments of the struck hotels.” The need for “united militant mass picket lines, united mass demonstrations” to force the owners’ association to grant the demands was stressed.

The left wing union (the F.W.I.U.) “decided to establish this necessary unity in spite of the opposition” of the Amalgamated leadership which has consistently turned down such proposals. Six hundred strikers at Bryant Hall, under leadership of the F.W.I.U., marched to the Madison Square Garden mass meeting Wednesday night, Jan. 3I, and pleaded for common struggle: the welding together of all the rank and file in joint strike action- those of the A.F. of L., the Amalgamated and the F.W.I.U.

Mr. Fields, the Amalgamated leader, has appealed to Mrs. Eleanor M. Herrick, chairman of the Regional Labor Board, for negotiations. The latter refused. Then Fields in tum rejected the proposal of the workers for mass demonstrations at the Regional Labor Board headquarters to enforce negotiations with the bosses- negotiations carried on by means of a broad rank and file committee. But negotiations without the spread of the strike will be of as much avail as those during the Weirton, Budd, Philadelphia Rapid Transit, Edgewater and Chester Ford strikes. The result in the latter cases was to call off the strike while the Regional Labor Board pondered the merits of the case- and the workers are back on the job, defeated, soldout.

Friday, Feb. 1, uncovered the following development: the leadership of the Amalgamated had sent out feelers to the hotel owners requesting settlement on the following basis:

1. No decrease in wages- the same scale that existed at the strike’s outbreak.

2. No increase in hours.

3. Recognition of the Amalgamated Union.

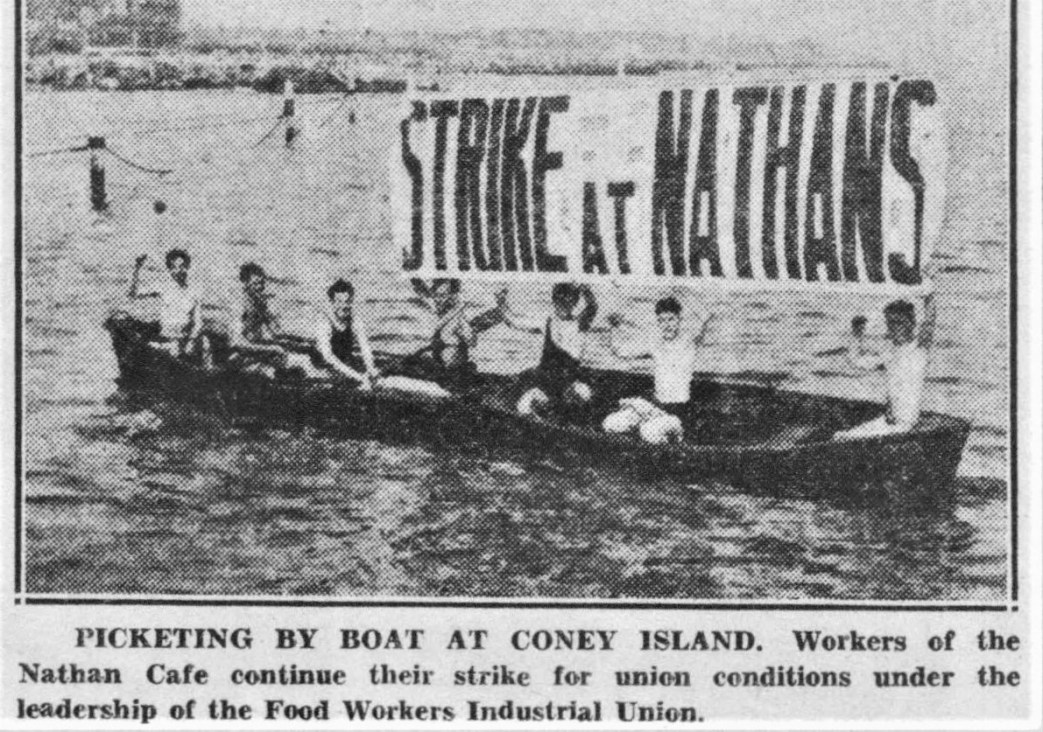

This is a complete turn-about-face, abandonment of the original demands of the strikers who had specifically raised economic demands for a forty-hour week and a $20-aweek wage. Having refused joint action proffered by the industrial union-and the proposal that all forces spread the strike- the Amalgamated leaders are now ready to settle on terms which mean one thing- recognition of the Amalgamated. The F.W.I.U. calls for increases in pay worked out by the strikers themselves in each shop-for a decrease in the outrageously long hours and for recognition of any union for which the majority of workers in their respective shops vote. (Among the hotels striking under the F.W.I.U. are the New Yorker, the Park Central, Alamac and the Taft. The Hyde Park has settled, the workers winning substantial increase in pay and recognition of the Union. The Maison Royale and the Bijou have also settled on terms advantageous to the F.W.I.U. strikers)

By abandoning the demand for the increase in wages the leaders of the Amalgamated permit the continuation of the present hopelessly inadequate wages. In the Park Central Hotel, for instance, waiters labor for no pay the first week, but receive the munificent sum of fifty to sixty cents a day in tips. They are later given fifty cents a day wages, and sometimes forced to do the work of the porters, who are dispensed with. In the banquet department of the same hotel, waiters received seventy-five cents a day, and only part of the tips intended for them, since the manager, a Mr. Smith, receives the tip money first and then “distributes” it among “the boys.”

A settlement on the Amalgamated terms would leave the striking waiters with their long hours. At the Hotel Taft they reported work from 6 :30 a.m. to 4 p.m. with no time for lunch. One striker declared he had lost twelve pounds in three weeks. It is generally known that twelve hours per day is the usual schedule of hours for room service waiters.

The strike continues- but unless unity is achieved the hotel workers trudging up and down the sidewalks of New York, their strike signs on their backs, will lose out. They face the police, the bitter winter weather, the strike-breakers, with heroic courage; but their disunity may defeat them. And then the starched shirts and silk-hatted guests at the Waldorf-Astoria can order their meals in peace once more.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v10n06-feb-06-1934-NM.pdf