First written in 1913 as an introduction to a four-volume German-language collection of Marx and Engels’ correspondence, this excerpt was first translated as part of a collection of Lenin on Engels for the 40th anniversary of his death in 1935.

‘Engels as One of the Founders of Communism’ (1913) by V.I. Lenin from Lenin on Engels. International Publishers, New York. 1935.

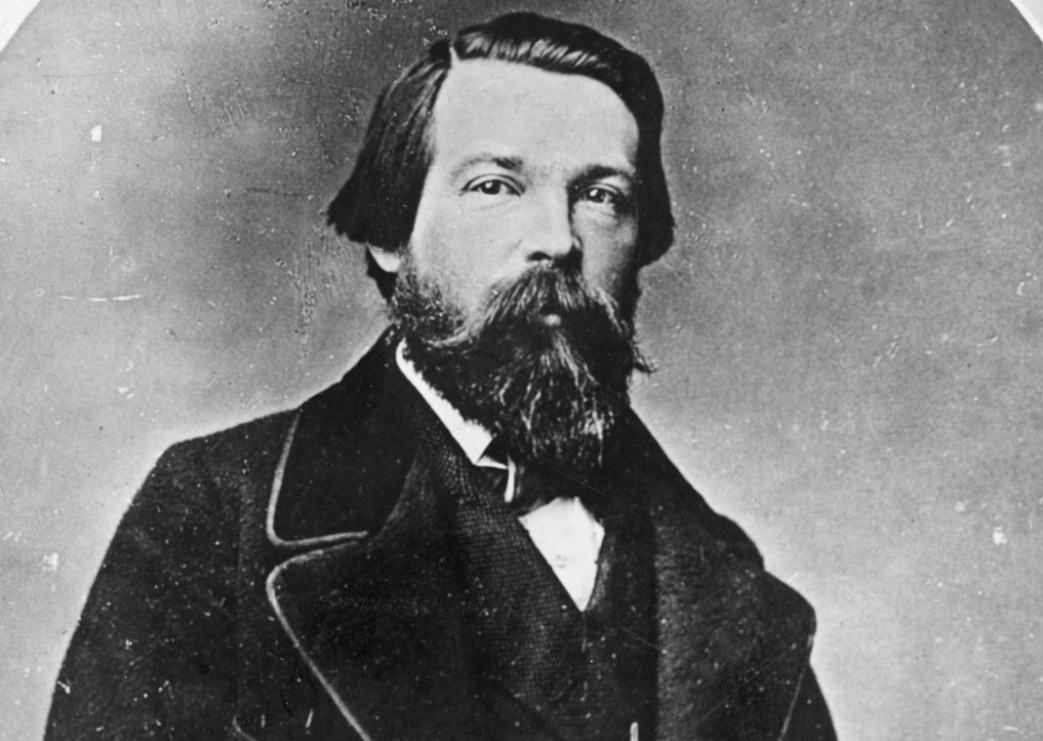

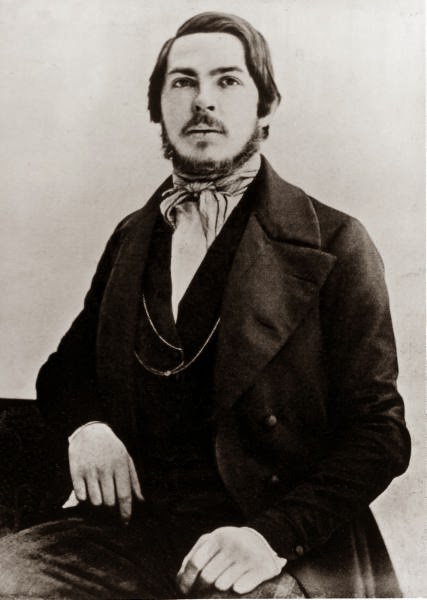

THE CORRESPONDENCE opens with the letters of the twenty-four year old Engels to Marx in 1844. The situation in Germany at that time is brought into striking relief. The first letter is dated the end of September 1844 and was sent from Barmen, where the family of Engels lived and where he himself was born. Then Engels was not quite twenty-four years old. He is weary of the family surroundings and is endeavoring to tear himself free. His father-a despotic and religious manufacturer-is indignant with his son for running about to political meetings and for his communist convictions.

“Were it not for mother, whom I dearly love,” Engels writes, “I would not have stood it even the few days which still remain before my departure. You cannot imagine,” he complains to Marx, “what petty reasons, what superstitious fears are put forward here, in the family, against my departure.”

While Engels was in Barmen, where he was delayed a little longer by a love affair, he gave in to his father and for two weeks he went to work in the office of his father’s factory.

“Commerce is abominable,” he writes to Marx. “Barmen is an abominable city, abominable is the way they while their time away here, and it is particularly abominable to remain not only a bourgeois but even a manufacturer, i.e., a bourgeois who comes out actively against the proletariat.

“I console myself,” continues Engels, “by working on my book on the condition of the working class.” (This book appeared, as is known, in 1845 and is one of the best in the socialist literature of the world.) “Well, for outward appearances a communist may remain a bourgeois and the beast of burden of huckstery, as long as he does not engage in literary pursuits; but to carry on, at one and the same time, wide communist propaganda and engage in huckstery, in industrial business–this is impossible. Enough, I will go away. On the top of it the sleepy life in the family- Christian and Prussian through and through-I cannot stand it any longer. I might in the end become a German philistine and introduce philistinism into communism.”

Thus wrote young Engels. After the Revolution of 1848 life forced him to return to his father’s office and to remain there for many long years “the beast of burden of hucksters,” but, nevertheless, he stuck to his guns and created for himself not a Christian and Prussian but quite another comradely atmosphere, and he succeeded in becoming for his whole life a relentless enemy of the “introduction of philistinism into communism.”

Public life in a German province in 1844 resembled that in Russia in the beginning of the twentieth century before the 1905 Revolution. All were rushing to politics, everywhere there was seething indignation and opposition against the government. The priests attacked the youth for their atheism and the children in bourgeois families quarreled with their parents for their “aristocratic treatment of the servants or workers.”

The general spirit of opposition found its expression in everybody declaring himself a communist.

“The Police Commissary in Barmen is a communist,” writes Engels to Marx. “I was in Cologne, in Dusseldorf, in Elberfeld-everywhere, on every step, you come across communists!”

“One ardent communist, an artist, a caricaturist named Seel, is going to Paris in two months. I am giving him an introduction to you. You will all like him. He is an enthusiast, loves music and will be useful as a cartoonist.”

“Miracles are happening here in Elberfeld. Yesterday (this was written on February 22, 1845), in the biggest hall, in the best restaurant of the city, we held our third communist meeting. The first meeting was attended by 40 persons, the second by 130 and the third by 200 at least. The whole of Elberfeld and Barmen, from the moneyed aristocracy to the petty shopkeepers, was represented, with the exception only of the proletariat.”

These are Engels’ exact words. In Germany, they were all communists then, except the proletariat. Communism was then a form of expression of the opposition moods of all, and most of all–of the bourgeoisie.

“The most stupid, the most lazy and most philistine people, whom nothing in the world interested, is simply becoming enraptured with communism.”

The chief preachers of communism were then people like our Narodniki, “Socialist-Revolutionaries,” “Narodnik Socialists,” etc., in reality well-meaning bourgeois more or less furious with the government.

And in such a situation, among countless numbers of would-be socialist tendencies and fractions, Engels was able to force his way towards proletarian socialism, without fearing to break with a mass of good people and ardent revolutionaries but bad communists.

1846. Engels is in Paris. Paris is bubbling over with politics and discussion of various socialist theories. Engels ravenously studies socialism and makes the personal acquaintance of Cabet, Louis Blanc and other outstanding socialists; he runs about visiting newspaper editors and attending various circles.

His main attention is directed to the most serious and most widespread socialist teaching of that time- Proudhonism. Even before the publication of Proudhon’s Philosophy of Poverty (October 1846 ; Marx’s reply-the famous Poverty of Philosophy appeared in 1847), Engels criticized with relentless sarcasm and remarkable depth the main ideas of Proudhon which were then particularly taken up by the German socialist Grun. His excellent knowledge of the English language (which Marx mastered much later) and English literature enabled Engels at once (letter of September 18, 1846) to cite examples of the bankruptcy in England of the notorious Proudhonist “labor bazaars.” Proudhon disgraces socialism, Engels exclaims indignantly. According to Proudhon the workers must buy out capital.

Engels at twenty-six simply destroys “true socialism.” We find this expression in his letter of October 23, 1846 (long before the Communist Manifesto), where Grun is named as its chief representative. “Anti-proletarian, petty-bourgeois and philistine” teaching, “empty phrases,” all sorts of “general humanitarian” aspirations, “superstitious fear of ‘crude’ communism” (LoffeLKommunismus, literally “spoon communism”), “peaceful plans of making humanity happy”-such are the epithets applied by Engels to all species of pre-Marxian socialism.

“The Proudhon Association’s scheme,” writes Engels, “was discussed for three evenings. At first I had nearly the whole clique against me, but at the end only Eisermann and the other three followers of Grun. The chief point was to prove the necessity for revolution by force” (October 23) 1846)…

“In the end I got furious…and made a direct attack” on my opponents which “enabled me to lure” them “into an open attack on communism…I announced that before I took part in further discussion we must vote whether we were to meet here as communists or not…This greatly horrified the Grunites” and they began to assure us that “they met together ‘for the good of mankind’…Moreover they must first know what communism really was…I gave them an extremely simple definition” so as to admit of no subterfuges on the gist of the question…”I therefore defined,” writes Engels, “the objects of the communists in this way: ( I ) to achieve the interests of the proletariat in opposition to those of the bourgeoisie; ( 2 ) to do this through the abolition of private property and its replacement by community of goods ; (3) to recognize no means of carrying out these objects other than a democratic revolution by force.” (Written one and a half years before the 1848 Revolution.)

The discussion concluded by the meeting adopting Engels’ definition by thirteen votes against two Grunites. These meetings were attended by nearly twenty journeymen carpenters. Thus in Paris, sixty-seven years ago, the foundations were laid for the Social-Democratic Party of Germany.

A year afterwards, in his letter of November 24, 1847, Engels informs Marx that he has prepared a draft of the Communist Manifesto, declaring himself, by the way, against putting it in the form of a catechism as previously proposed.

“I begin,” writes Engels: “What is communism? And then straight to the proletariat-history of its origin, difference from former workers, development of the contradiction between proletariat and bourgeoisie, crises, results…In conclusion the party policy of the communists…”

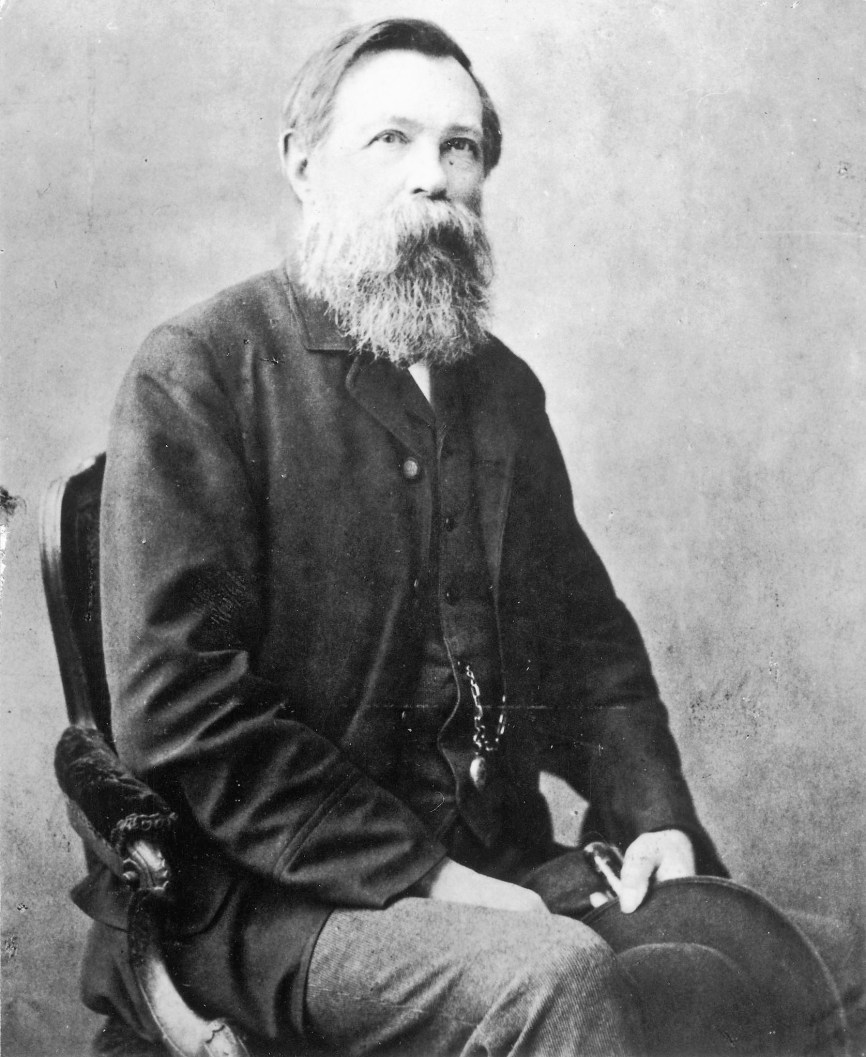

This historical letter of Engels on the first draft of the work which traversed the whole world, and which, up to the present, is true in all its fundamentals, and is as full of life and as modern as if it were written yesterday, clearly proves that the names of Marx and Engels are justly placed side by side, as names of the founders of modern Socialism.

Lenin on Engels. International Publishers, New York. 1935.

PDF of original pamphlet: http://palmm.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/ucf%3A4903/datastream/OBJ/download/Lenin_on_Engels__On_the_40th_anniversary_of_Engel_s_death.pdf