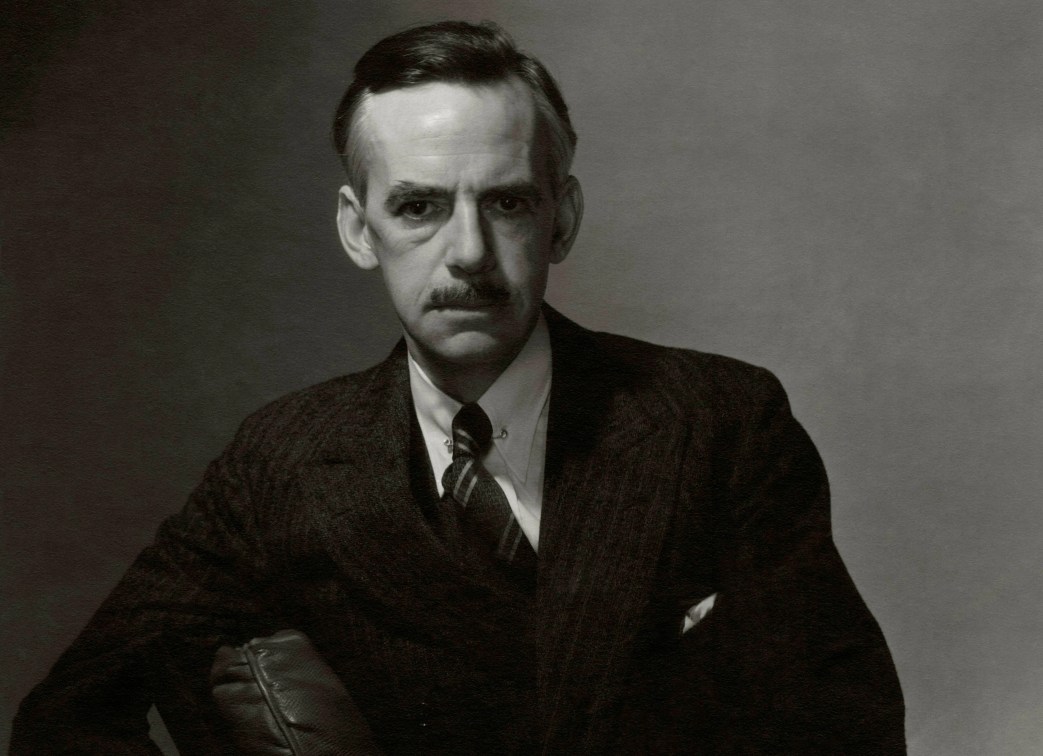

First president of the Writers Guild of America John Howard Lawson, playwright, screenwriter, Marxist literary critic, and member of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten, looks at the ‘technique and social philosophy’ of the towering figure of twentieth century drama in the United States, Eugene O’Neill, as exemplified in his nine-act, 1928 work ‘Strange Interlude.’

‘Strange Interlude: Eugene O’Neill’s Technique and Social Philosophy’ by John Howard Lawson from New Masses. Vol. 16 No. 7. August 13, 1935.

EUGENE O’NEILL’S career as a playwright is of special significance, both because of the abundant vigor and poetic richness of his earlier dramas and because of the tragic confusion which casts a shadow across his later work. This confusion is not merely a personal matter; the author’s philosophy is a reflection of the middle-class thought of his period and reflects a general trend in the middle-class theatre. The philosophy of mystic pessimism has eaten like a disease into the structure of the modern drama. Since by its very nature this philosophy negates action and denies logic, it makes unified dramatic development impossible.

Strange Interlude is a revealing example of O’Neill’s later technique and of the social concepts on which this technique is based.

What is the structural character of Strange Interlude? The story of the play, expressed in its simplest terms, is the story of a married woman who has a child by a man who is not her husband. The plot rests chiefly ona sense of foreboding, the threat of horrors which never concretely materialize. In the first three acts, Nina marries the dull Sam Evans and intends to have a baby. She then discovers there is insanity in her husband’s family. We then find that these three acts have been exposition to prepare for the real event: since the threat of insanity prevents Nina from having a child by her husband, she selects Dr. Darrell as the prospective father. We watch eagerly for the consequences. But one may say, literally, that there are no consequences. In Act V, Nina wants to tell her husband and get a divorce, but Darrell refuses. In Act VI, Darrell threatens to tell Sam, but Nina refuses. In Act VII, the activity centers around the child (who is now eleven): the boy’s suspicions now threaten to upset the apple cart. But in the next act (ten years later) everybody is on the deck of a yacht in the Hudson River watching Gordon win the big boat rate: “He’s the greatest oarsman God ever made!”

This outline may seem unfair. There are those who will say that I am applying an arbitrary technique and that O’Neill has brilliantly realized the psychological conflict. I can only reply that psychological conflict must be expressed in action. The failure to bring the action to a head means a failure to understand the psychological roots of the drama.

Now let us consider the asides. It is generally assumed that these serve to expose the inner secrets of character. This is not the case. Nine-tenths of the asides deal with plot and superficial comments. The characters in Strange Interlude are very simply drawn; and they are not at all reticent in telling their inmost feelings in direct dialogue. For instance in Act III, Mrs. Evans says, “I used to wish I’d gone out deliberately in our first year, without my husband knowing, and picked a man, a healthy male to breed by, same’s we do with stock.” Coming from an elderly farm woman, one would reasonably expect this to be an aside, but this is direct dialogue. Mrs. Evans’s asides (like those of the other characters) are devoted to such expressions as “He loves her!…He’s happy!…that’s all that counts!” and “Now she knows my suffering…now I got to help her.”

Then are we to conclude that the asides are a whim, a seeking after sensation? Not at all. They serve a very important structural purpose. They are used to build up the sense of foreboding: again and again there are comments like Darrell’s in Act IV:

“God, it’s too awful! on top of all the rest! How did she ever stand it? She’ll lose her mind too!” But the asides have a much deeper use: in every scene they foretell what is about to happen and blunt the edge of conflict. What might be a clear-cut scene is diluted by needless explanations and by annotating the emotions.

Thus we discover that both the asides and the length of Strange Interlude are dictated by a psychological need: to delay, to avoid coming to grips with reality. The function of the asides is to cushion the action, to make it oblique; this same obliqueness creates the need for spreading the story over nine long acts.

Strange Interlude reaches no climax and no solution. However, the final scene of the play contains a fairly thorough summing up of the author’s position and gives us a further key to O’Neill’s philosophy. It is not enough to say that the drama simply ends on a note of frustration. O’Neill tells us a great deal more than that: he shows that he is trying to avoid frustration, he is twisting and turning in an effort to find an affirmative meaning.

The last act of Strange Interlude begins with a scene between the young lovers, Madeleine and Gordon. Here we have the idea of a new life: the saga of love and passion will be repeated. Marsden offers a rose to Madeleine, saying mockingly, “Hail, Love, we who have died, salute you!” One expects the playwright to emphasize this line of thought, but he turns sharply away from it, turning to Gordon’s bitterness against his mother, his feeling that she never really loved the man whom he regards as his father. Nina, tortured for fear Darrell will tell the boy the truth, asks her son a direct question: “Do you think I was ever unfaithful to your father, Gordon?” Gordon is shocked and horrified…he blurts out indignantly: “Mother, what do you think I am-as rotten-minded as that!” Here is the germ of a social idea which might lead to something if the conflict between mother and son were developed. However, O’Neill cuts it short at this point: Gordon leaves, soliloquizing as he goes, “I’ve never thought of that!…I couldn’t!…my own mother! I’d kill myself if I ever even caught myself thinking…!” It is significant that Gordon, who represents the new generation, leaves the stage with these negative words.

Darrell then asks Nina to marry him and she refuses, saying, “Our ghosts would torture us to death!” Thus the idea of the repetition of life turns into one simple fact that Nina has built her life on a lie and that this accounts for all her troubles. Her son, as he leaves the stage, tells us that he is just as cowardly as his mother: “I’ve never thought of that!…I couldn’t!”

It is to be noted that this fear of truth is not regarded as personal cowardice, but as destiny. O’Neill endeavors to rationalize this idea of Fate in terms of psychoanalysis. Fate is directly identified with the mother (and father) complex. But this is an incorrect and unscientific approach to psychoanalysis. Freud (and other psychoanalysts) represent the ego in continuous conscious and subconscious conflict, not helplessly under the domination of static complexes.

In spite of his reliance on the mother complex, O’Neill shows that this too leaves him dissatisfied, feverishly uncertain. The last scene of Strange Interlude contains a welter of unfinished ideas-references to religion, pure science, womanly intuition, “mystic premonitions of life’s beauty,” the duty “to love that life may keep on living,” etc. The pain of the author’s search lends dignity to his confusion. But it is obvious that this confusion cannot lead to situations which are dynamic, meaningful or clearly outlined.

Asimilar mystic content, and a similar dramatic flabbiness, are to be found in a wide variety of current plays. It is generally true that the architecture of the modern play is off center. The preparation is excessive and the event is ignored or minimized. What Freytag called the “erregende moment” or “firing of the fuse” is unconscionably delayed (or altogether omitted).

Ibsen avoided preparation, beginning his plays at a crisis, illuminating the past in the course of the action. This method has now been carried to a further extreme: the crisis is diluted and the backward-looking or expository moments are emphasized- so that the play (in many cases) is all exposition and no crisis.

The playwright whose attitude toward life is negative and mystic will naturally express a dread of action, a lost desire for emotional stability. He achieves this by delaying or avoiding the moment of conflict. This may satisfy the playwright, but it does not satisfy dramatic construction. When the dramatist runs away from life, he runs away from his own play.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v16n07-aug-13-1935-NM.pdf