‘Workers’ Children Defy Patriots’ by Beatrice Carlin from Labor Defender. Vol. 5 No. 9. September, 1930.

THE W.I.R. Children’s Scout Camp at Van Etten, N.Y., has just had an experience with American “patriotism” that must make a lasting impression on the one hundred children, mostly of Finnish parentage, who were in the camp, and on all the adult workers who witnessed the senseless frenzy of those small-town “patriots.”

When the camp was first opened, word spread to a neighboring town across the state line, Sayre, Pa., that “Red activities” were going on in the New York camp. The Rev. Mr. Shepson, a revivalist preacher, wrote an inflammatory article in a local newspaper concerning the camp, and certain super-patriots undertook to “learn” the children respect for the flag. They organized a Ku Klux Klan demonstration in front of the camp, and burned a cross of fire; on another occasion a fiery wheel was burned near the camp. As this threat of terror failed to intimidate the children or the leaders of the camp, a group was delegated by the American Legion of Athens, Pa., to present a large American flag to the children’s camp, and to make them fly it.

Driving up to the camp about twenty strong, on August 8, they offered the flag to the two young leaders of the children, Mabel Husa, 20, and Ailene Holmes, 23, both members of the Young Communist League. The girls politely ref used the gift, stating that there was no law to compel any camp to fly a flag, and that they did not wish to fly it. When pressed for a reason, they said the flag represented the interests of the boss class of America, the exploitation of the workers and farmers, and the imperialistic repression of colonial peoples.

The visitors then tried to force the two girls and the children to kiss the flag by pushing it into their mouths. The children resisted, and several of them were roughly handled. The children formed into line, and led by Comrades Husa and Holmes, began to sing their camp songs, and to shout slogans against their enemies. “Down with the enemies of our camp-boo, boo, boo”; “Down with the Ku Klux Klan”; “Down with the American Legion,” giving three boos after each shout. They marched with their camp banner, a Red banner inscribed with the words, “Van Etten W.I.R. Scout Camp,” a hammer and sickle, and the Pioneer slogan, “Always Ready.”

The sight of this banner infuriated the patriots and they attempted to take it away from the children. One of the boys, about twelve years old, took the camp banner, and climbed a telegraph pole with it. This was interpreted by the visitors as putting the Red banner “above” the American flag. Several of them grabbed the two girls, put them forcibly into an automobile, and drove them down to the Klan grounds and then to the Justice of the Peace of Van Etten, to have them arrested.

The justice, William Westbrook, is an old man, close to seventy years. Hesitating to offend the Finnish farmers who have settled in that neighborhood, he refused at that time to issue awarrant for the arrest of the two girls. He was threatened with lynching by the Klan if he did not make the arrests. Finally, he issued a warrant, sworn out by a Mr. Dennis, ex-commander of an American Legion post in Pennsylvania, and Mrs. Daisy Felt, member of a patriotic organization in Waverly, New York. The girls were arrested on the basis of an obscure subdivision of a section of the penal code of New York, providing for the punishment by six months’ imprisonment and fifty dollars fine, of anyone who “insulted” the flag. The patriots swore that the girls had instigated the children and had themselves been guilty of saying: “To hell with the American flag,” “Down with the American government,” “We will make a dish rag out of their flag in four years”; and also accused them of leading the children in pledging allegiance to the Red flag of Soviet Russia.

A representative of the Workers International Relief and International Labor Defense secured a postponement of the trial, which angered the “patriots.”

Armed with black-jacks and revolvers and in an ugly mood, they drove to the camp grounds. We met their vanguard, and asked them to leave the grounds of the camp. They responded that “everything belonged to Uncle Sam,” and gave an ultimatum to “clear the children out of the camp in thirty minutes.”

The children had had a mass meeting during the day, and had voted unanimously to stick by the camp, and not to allow themselves to be intimidated into dispersing before the scheduled break-up on Saturday morning, The spokesmen for the camp were able, because of the perfect morale of the children, to defy the raiders, and to accept their challenge with the declaration that the camp would fight back if the mob made any move to attack them.

In the meantime, someone had raced down to the village, and put in a call for the county sheriff and the state troopers. These veteran enemies of the working class, who never lose an opportunity of smashing a demonstration of the workers against unbearable conditions of exploitation, or of breaking the heads of strikers on picket duty, had known for two weeks of the molestation of the camp by the fascist baiters of the children, but had made no move for the protection of the camp. It took these guardians of “law and order” about five hours of gentle persuasion to clear the camp grounds.

The trial of the two girls, Mabel Husa and Ailene Holmes, was conducted in the tiny village court room, crowded to overflowing, on the one side with sympathetic workers and farmers from the immediate neighborhood; on the other side, with angry, murmuring members of the Klan, the American Legion and the local patriots under their influence. All the approved methods were used by these hypocrites in the name of “The People,” who were called the plaintiffs. Hysterical references to “the boys who died in the war for the flag”; the spectre of a “Red revolution” within four years, made by the attorney for “The People,” called on the aged justice to stamp out Communism in America by putting the two young women behind prison bars.

The sentence was a fine of fifty dollars and three months’ imprisonment for each girl.

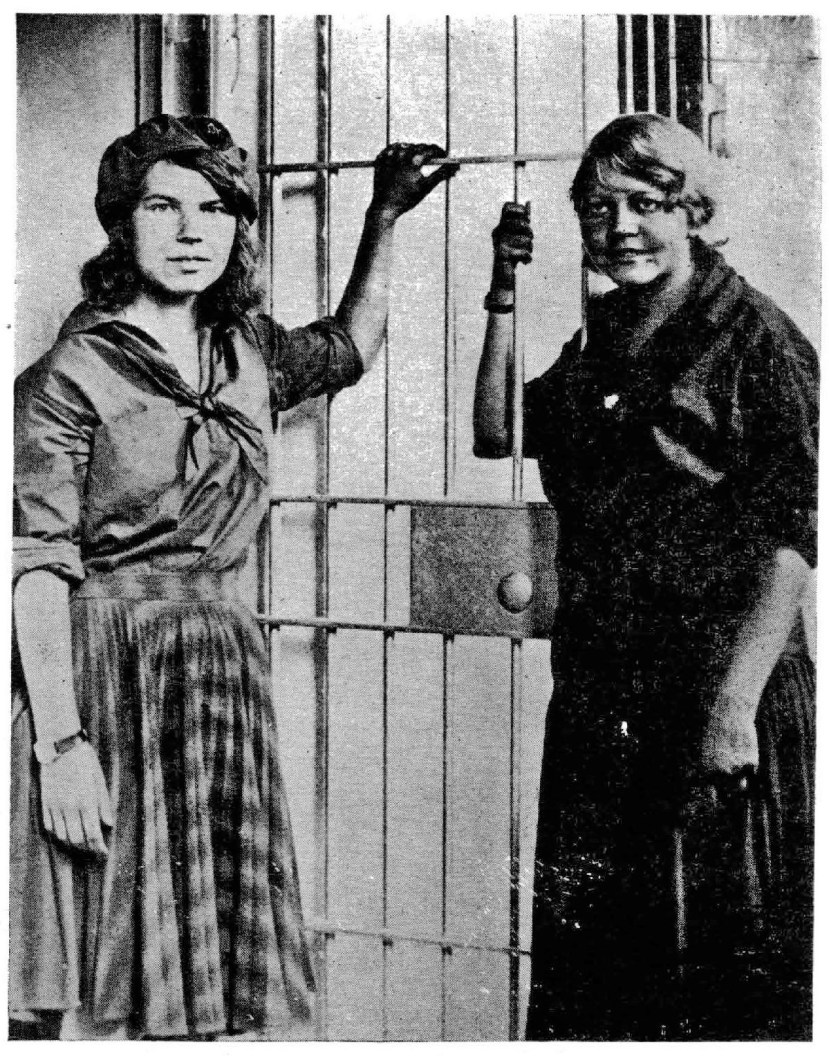

The two girl comrades, Mabel and Ailene, unfailingly cheerful, courageous class fighters, were remanded to the county jail, when an appeal was refused pending eight days’ written notice.

The attempted break-up of the Workers International Relief Children’s Scout Camp must be answered with the building of more and bigger camps by the Workers International Relief. Class-conscious working class parents must boycott the bourgeois Boy and Girl Scout movement. A concerted effort must be made on the part of all friendly and affiliated working class organizations to draw workers’ and farmers’ children out of the bourgeois Boy and Girl Scout camps and into the Workers International Relief working class Scout Camps.

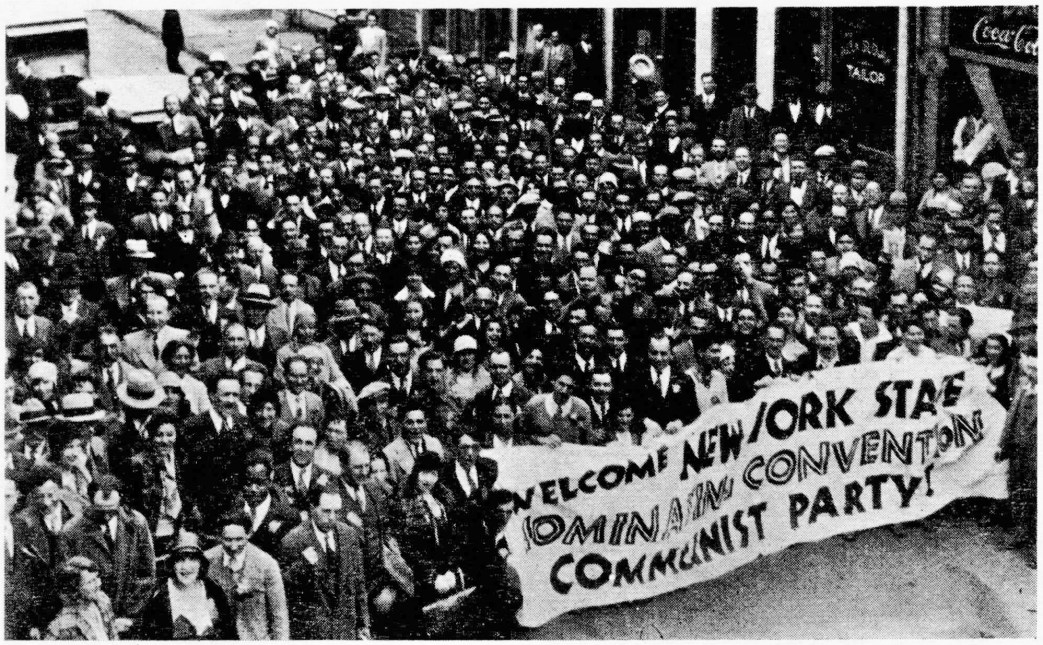

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1930/v05n09-sep-1930-LD.pdf