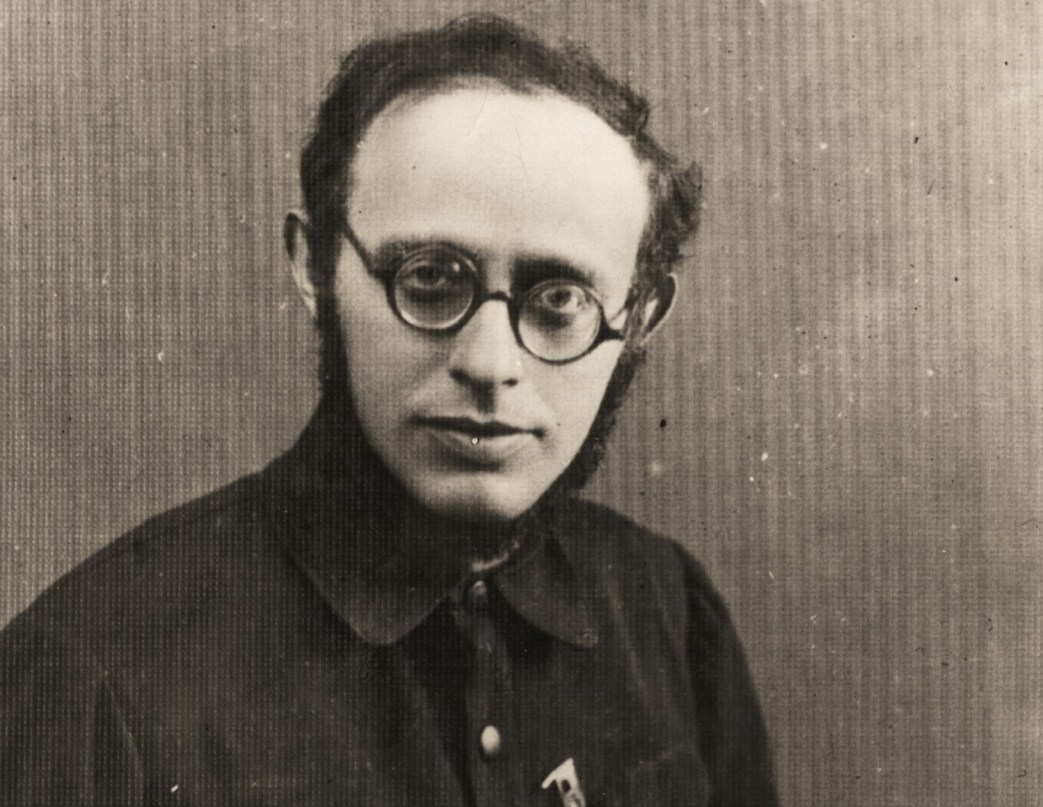

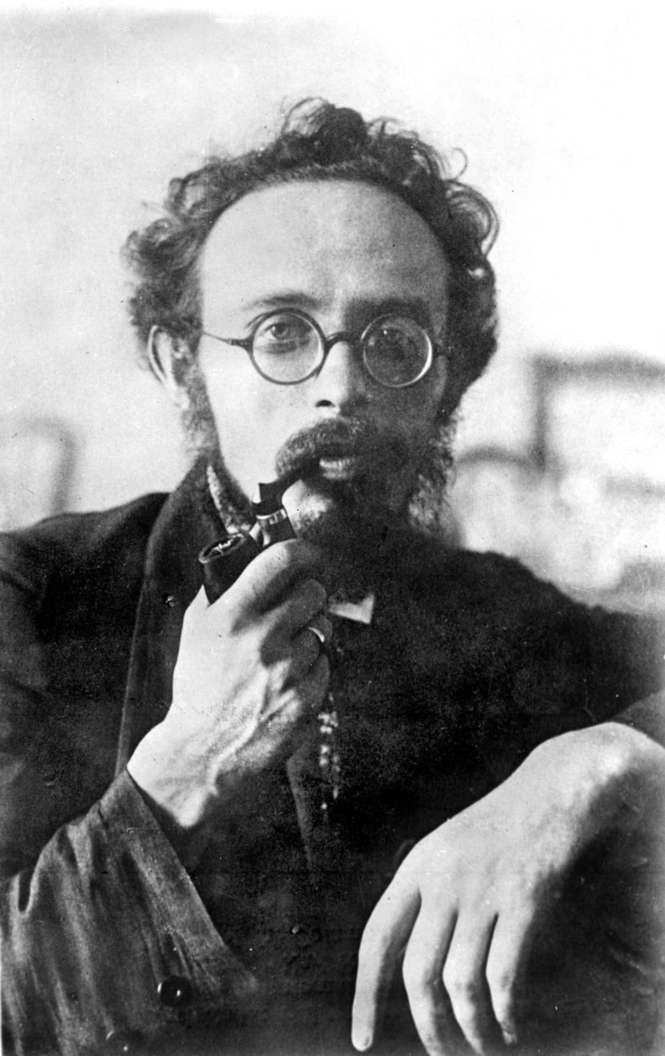

‘Soviet Russian Concessions to Capital’ by Karl Radek from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 7. February 12, 1921.

WHEN the working class of Russia assumed power in November, 1917, neither the bourgeois world nor the Socialist world believed that this power would last two months, not to mention two years. The negotiations of German imperialism with Soviet Russia were only the result of the straits in which Germany found itself as a consequence of the war: German imperialism desired to conclude peace in the East, even with a purely transitory government, under the well-founded impression that even though the Bolsheviki might disappear, no party and no government in Russia could within a calculable period mobilize the peasants. Soviet Russia however needed peace, not only because it had no army at all, but because it could only reach the stage of reality by obtaining a breathing spell. At the time of the Brest negotiations, Soviet Russia was only a program, existed only in the declarative decrees of the Council of People’s Commissars. Not even Tsarist absolutism had been completely destroyed in its lower organs at that time, nor had feudal landlordism been wiped out. The forms of the Soviet Government in city and country were still an experiment, not an organism. The Soviet Government was faced with the choice of either waging, with the help of the Allies—as a government of the revolutionary partisan party of the Urals, a guerrilla warfare against German imperialism, and to permit Russian capital to carry out its restoration under the protection of German bayonets, or to pass through the Golgotha of Brest and thus to carry out, at the price of a national humiliation, the task of immediately putting down the bourgeoisie and organizing the proletariat.

The fact that the policy of the Soviet Government, based on the conviction that the process of disintegration of world capitalism would not be retarded by the Brest peace, but accelerated, was a proper policy, has been proved not only by its late victories, by the fact that Soviet Russia, between the devil and the deep sea so to speak, was able to collect and organize itself to the extent of forcing from the representatives of victorious Entente imperialism the admission, a year after the collapse of German imperialism, that: “Bolshevism cannot be put down with the sword.” The Brest peace, in spite of its predatory character a positive benefit to Soviet Russia, since it ended the great war, was not forced by Soviet Russia out of its own power, nor by the German workers; the peace of Brest was brought about by the pressure of Entente armies in the west. Should the victorious imperialism of the Entente now conclude a still more unfavorable predatory peace, this peace, if it only affords Soviet Russia the possibility of existence, will be a fundamental breach in the capitalistic system of states, for this peace will be a result of the resistance offered by Soviet Russia with its own powers, a result of the aid given Soviet Russia by the world proletariat. But why should Soviet Russia, which cannot be destroyed by the sword, make any compromise peace at all with the Entente? Why should it not wait for the moment when the disintegration of Entente capitalism has progressed at least so far that this capitalism must grant an honest peace to Soviet Russia? The answer to this question is very simple. During the world war, which was being prolonged by the policy of all the states, it was possible to count upon a swift catastrophe of world capitalism, on a reaction of the popular masses in various countries, if once the general slaughter should allow them no other means of escape. At the conclusion of the Brest treaty, the Soviet Government estimated the breathing spell afforded by this peace as a very short one; either the world revolution would soon come and rescue Soviet Russia, or Soviet Russia would go down in the unequal conflict—such was our view at that time. And this conception was in accordance with the situation at that moment.

The collapse of German imperialism, the inability of the Allies to put down Soviet Russia by military means, and simultaneously the fact that the world war has since been ended, that the demobilization crisis has been overcome, that the world revolution has not broken up the capitalist world in the form of an explosion, but in the form of a gradual corrosion—this fact completely alters the situation, the conditions, of the foreign policies of the Soviet Government.

On the one hand the Soviet Government cannot reckon on a swift mechanical liberation through a mass movement that would completely overthrow the Clemenceaus, Lloyd Georges, and all they stand for, and on the other hand the Soviet Government may be mathematically certain that the process of capitalistic disintegration will continue and lighten its burdens. But as this is a long process, Soviet Russia cannot escape the question of seeking a modus vivendi with those states that are still capitalistic. If tomorrow the proletarian revolution in Germany or France should be victorious, Soviet Russia’s position would be much easier, for two proletarian states, organized economically and militarily—can exert a greater pressure on the capitalist world. But they will nevertheless still be interested in concluding peace with the as yet capitalist states, if only for the reason of having an opportunity at last to take up economic reconstruction.

Soviet Russia could not be put down, and we are certain that if the Entente states will not grant Soviet Russia a capitalist peace at this moment, Soviet Russia will continue to hunger and to fight, and they will be obliged to grant our country a better peace later on. To put down a country with Soviet Russia’s resources, by means of blockade, will require a period that will exceed the length the imperialistic epoch in the Entente countries has still to run. But it is clear that if Soviet Russia must continue to fight for very long it cannot take up its economic reconstruction. The war makes it necessary to put its weakened productive forces at the service of the manufacture of munitions, to use its best forces for the practice of war, to apply its ruined railways for the transportation of troops. The distress of war obliges the energy of the state to be centralized in the hands of the executive, threatens the Soviet system, and, what is most important, in the long run menaces the complete using up of the best elements of the working class. The Soviet Government has performed a superhuman task in opposing these conditions. Its accomplishments in the field of instruction, in spite of all the distress, impresses even now those bourgeois opponents who are honest (read Goode’s report in the Manchester Guardian). In two or three years Soviet Russia will dispose of hundreds of thousands of new organizational and cultural talents.

How seriously our leaders regard the dangers of reconstruction, of the chinovnik in a new form, is shown with complete clearness by the discussions in the party convention of the Bolsheviki in March, 1919, the minutes of which—constituting a very instructive document—have been recently published. But war is war. War is a cruel destroyer, and if war can be concluded by making sacrifices, the sacrifices must be made. It is un- fortunate, to be sure, that the Russian people should be obliged to grant mining concessions to English, American, and French capitalists, for it could make better use of the metals itself than to apply them for paying tribute. But, so long as Soviet Russia must wage war, it can not only not mine ore, but is even obliged to throw its miners into the jaws of war. If the dilemma were this: economic Socialist reconstruction, or war against world capital, which is restricting the Socialist reconstruction, the only proper decision would be for war. But that is not the state of affairs. The question to be decided is this: Socialist reconstruction within the limits of a provisional compromise, or war without any economic reconstruction at all.

Already in the spring of 1918, the Soviet Government was faced with the question of economic compromise. When the American, Colonel Raymond Robins, on May 14, 1918, left Moscow for Washington, he took with him a concrete proposition of the Soviet Government, containing conditions for economic concessions (this proposition was published in the minutes of the First Congress of Russian Economic Soviets in the speech of Radek on the economic consequences of the Brest peace). Simultaneously, Bronsky, Assistant to the People’s Commissar for Trade and Industry, submitted in the first session with the representatives of the German Government practical proposals for the cooperation of Soviet Russia with German capital. Bruce Lockhart (the English representative) was confidentially informed of a basis for negotiations. We may admit that even in the midst of the world war we had a right to hope that immediate explosions would eliminate the necessity of making such concessions, but in principle we had already then determined on this policy of concessions, and it was a well-founded policy. So long as the proletariat has not been victorious in all the most important states, so long as it is not in a position to make use of all the productive forces of the world for purposes of reconstruction, so long as capitalist states exist side by side with proletarian states, for just so long will the proletarian states be obliged to conclude compromises, for there is under these circumstances neither a pure Socialism, nor a pure capitalism, but, in spite of territorial divisions between these two systems, they will be obliged to grant concessions to each other, on their respective areas. The extent of these concessions to be made to capitalism will depend on the power of the proletarian states, and on the number of such states in existence. No one has the right to deny that such concessions must be made unless he is ready to point out a method by which our opponents may be forced immediately to grant the proletariat in all countries a simultaneous victory.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n09-aug-28-1920-soviet-russia.pdf