A.M. Simons wrote what was for more than generation of U.S. Marxists THE textbooks of of U.S. history, ‘Class Struggles in America’ and ‘Social Forces in American History.’ Simons, like nearly all U.S. Marxists of the time, were members of what is now called the ‘Beard School’ (named for Charles and Mary Beard) in understanding U.S. history, which employed a ‘vulgar’ materialism in an ‘economic reductionist’ understanding of the past. No more so was this school, and its Marxist adherents, more broadly influential than in the understanding of slavery and the Civil War; where the abolitionism and even slavery, aside from a system of labor, became irrelevant as the conflict was reduced to the capitalist North and the semi-feudal South. An influence still widely felt. Here, Ernest Crosby, poet and essayist perhaps best described as a Left Tolstoyan, long active in radical circles, challenges that interpretation with a defense of the idealism and vision of the Abolitionists.

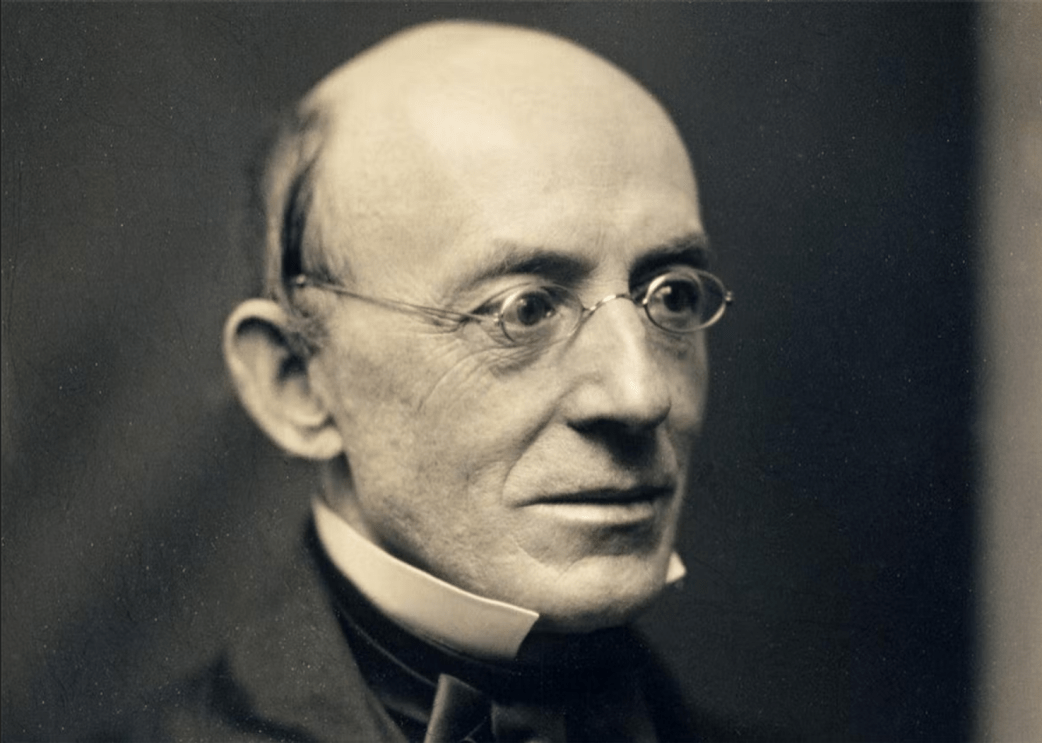

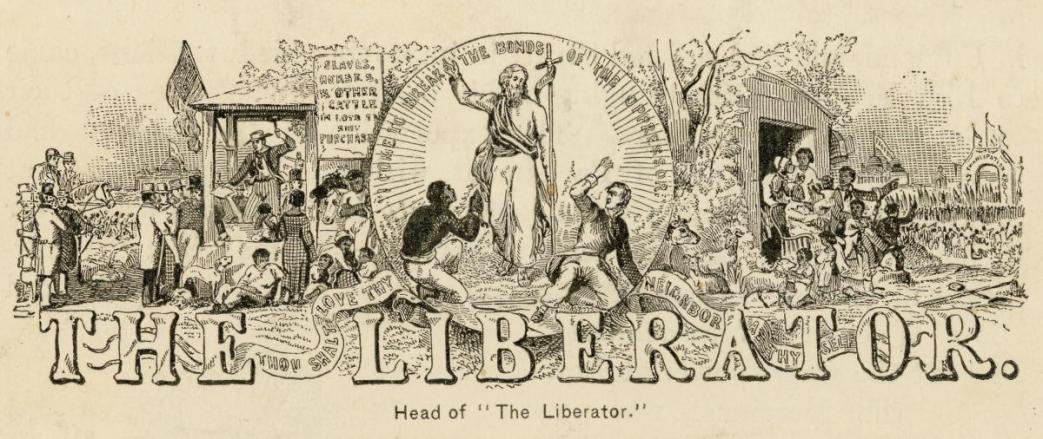

‘Garrison, and The Materialistic Interpretation of History’ by Ernest Crosby from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 6 No. 9. March, 1906.

THERE is a class of critics which denies the importance of Garrison’s services to the country on the ground that all idealists and reformers are mere empty voices, and that none but economic causes affect the condition of men. The world, according to these philosophers, crawls upon its belly, and its brain and heart follow submissively wherever the belly leads. This is known as the “economic interpretation of history,” and is particularly affected by Marxian socialists, who believe that state socialism is destined to be established by irresistible economic laws, and that their own idealism and agitation are altogether fruitless; which does not prevent them, however, from laboring and sacrificing themselves for the cause, like the typical idealist. This belief and this behavior is strangely like the Christian doctrine of predestination, the certain triumph of the church, and the fore-ordained election of the saints, which has never interfered with the missionary activity of believers. The disciple of Marx comforts himself with the materialist equivalent of the statement that all things work together for good, and his dogmatism is as strict as that of any Presbyterian sect. It is the old issue of fatalism and free will, the fatalist usually exerting himself to secure his ends much more strenuously than his adversary.

The most complete application of this theory of economic causes to the subject of slavery has been made by an acute socialist thinker, Mr. A.M. Simons, in a series of articles in the International Socialist Review of Chicago during the year 1903. According to him the idealism of Garrison and the Abolitionists— the growing belief in the immorality of slavery and the justice of the Remand for freedom, John Brown and his raid, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the battle songs of the North — all these things were phantasmagoria and the people were deceiving themselves.

“The real conflict was between the capital that hired free labor and the capital that owned slave labor.”

And Mr. Simons represents the Northern capitalists in the anticipation of a future struggle between themselves and their employes, as deliberately determining that the capitalists of the South should not enjoy the “privilege of an undisturbed industry.” It seems to me that anyone who can believe this can believe anything that he wishes to. The fact is that slave labor did not compete with the free labor of the North. The South had a practical monopoly of the production of cotton, tobacco, rice and sugar, and slavery was chiefly confined to that production. The relative cheapness or dearness of slave labor had consequently no appreciable effect on Northern labor; and if it had, it is absurd to suppose that Northern capital appreciated the fact or brought about the war for any such reason. It is true that the North desired a protective tariff for its manufactures, and that the South preferred free trade so that it might have a world-wide market for its cotton. It is true that North and South each desired to control the national government. But no war would have been fought if the South had not seceded; the South would not have seceded unless she had feared for the future of slavery; and slavery would not have been menaced except for the agitation of the anti-slavery people of the North with Garrison at their head.

As a matter of fact, human idealism enters into all the works of man; and the philosophy which asserts that poetry and religion spring from economic conditions and nothing else, is erroneous or at least one-sided. That mind and body are so intermingled that they reach upon each other, is undoubtedly true, and our extreme idealist needs to be reminded now and then that the bread and butter factor must not be forgotten; but to assert that mind is made of bread and butter is going much too far, and it ignores the commonest experiences of human consciousness. Man’s wish — man’s will — is a force to be dealt with. Even ordinary hunger involves wish and will in the choice of food. Is our present civilization governed partially by the yield of wheat? But wheat itself is a human creation. The first man who tasted a grain of wild wheat and liked it and proceeded to sow other similar grains was moved as much by fancy as by economic necessity. And there is hunger and hunger. There is a hunger and thirst for knowledge, and a hunger and thirst after righteousness, and many other hungers and thirsts which must all be reckoned with in the study of evolution. And man can see the workings of this side of evolution in his own mind. I have become a vegetarian, for instance, and I am unable to detect any economic reason for my change of diet. I know many others of whom the same is true. In time the increase in the number of such vegetarians will produce an appreciable effect upon the economic condition of mankind, and here clearly will be a change occasioned in large part by pure idealism. The same is true of socialism, and I know many leading socialists who so far from having been impelled to socialism by economic motives, would be economic losers by its victory. And so with the temperance movement, the peace movements, the movement for the prevention of cruelty to animals, and many others. I am conscious and every man Is conscious of doing things every day against mere economic interests, and I do not refer exclusively to philanthropy by any means. The millionaire who spends his money on a trip to Europe instead of saving it overrules his economic interests on account of his higher desire for novel experiences, and he does the same thing when he pays for a superfluous ornament on his house. To overlook men’s desires is to overlook life itself, and in the record of the living actions of men the thought precedes the thing. You cannot have a dinner without thinking it out beforehand, nor build a house without plans. You might wait till dooms-day for “economic conditions” to roast a potato for you. The will of man must intervene before the miracle is performed, and sometime he wills to rise above his economic conditions and refuses to bend before them.

In short, the “economic interpretation of history” is equivalent to the brick interpretation of a house (leaving the architect and the owner who ordered it built out of the question) — that is, no interpretation at all. Economic conditions are more often the limitation than the source of evolution. The exertion of our powers is more or less bounded by our materials, and events which are not economically possible are not likely to happen; but things are not yet in the saddle and the socialist movement, with its devoted and self-forgetful leaders, gives ample proof of it. It is curious to note that our extreme materialists call themselves “scientific socialists” and our extreme idealists, who deny the existence of matter, take the name of “Christian scientists.” True “science” lies between these extremes and perhaps it is wise to fight shy of those who advertise their “science” too conspicuously.

In the history of slavery the element of human will and initiative is particularly prominent. A sentimental bishop was the first to suggest the importation of Africans to America in order to relieve the Indians from the labor which their spirit could not brook. It was a philanthropic business at the start. Indians would not work, Negroes would. Here again the human factor asserted itself. The Cavalier immigrants of the South did not like to work, the Puritans of the North did; hence one of the reasons that slavery flourished only below Mason and Dixon’s line. Mr. Simons refers to this fact as “one of those strange happenings” called “coincidences.” The interesting point lies,” he goes on to say, “in the fact that in Europe it was just the Cavalier who represented the old feudal organization of society with its servile system of labor, while the Puritan is the representative of the rapidly rising bourgeoisie which was to rest upon the status of wage-slavery.” “Strange happening,” “coincidence,” “interesting point.” This is certainly most naive. There was no reason why slaves should not be employed in the North in raising wheat as well as in the South in raising cotton, except that the Northerners did not want them, and heredity as well as climate goes to account for the difference. Mr. Simons himself quotes from the work of an antebellum author a reference to German settlers who, “true to their national instincts, will not employ the labor of a slave.” And in fine, as if to show how little he is convinced by his own arguments, Mr. Simons says of this same volume (Helper’s “Impending Crisis”), “This book had a most remarkable circulation in the years immediately preceding the war, and probably if the truth as to the real factors which made public opinion could be determined, it had far more to do with bringing on the Civil War than did ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which involves an admission as to the latter book as well as to the former. Books and arguments and ideals had their leading part to play in the abolition of slavery, and the very adversaries of the belief cannot get away from it. “Public opinion” is and always has been a determining element in history, and it is swayed by novels and agitators and poets. Garrison still has his place in history.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v06n09-mar-1906-ISR-gog.pdf