Our history is hidden from us. When we think of intense, violent class struggle we do not often think of Rhode Island. And we would be wrong. Walter Snow vividly tells the story of 45,000 textile workers fighting for their lives in a battle against the companies, their gun thugs, police, and the National Guard which raged for a week in the Blackstone River Valley during September, 1934. We should all know the name of the Moshassuck Cemetery, where the workers retreated and made a desperate, heroic two-day stand among the gravestones, some of which are still marked by bullets today, and where fellow workers Charles Gorczynski, William Blackwood, Jude Courtmanche, and Leo Rouette fell.

‘Terror in Rhode Island as Textile Strike Grows’ by Walter Snow from New Masses. Vol. 12 No. 13. September 25, 1934.

WOONSOCKET, R.I.- WITH THE Communist Party outlawed in Rhode Island but with the textile strike more than 96 percent effective, militiamen and police are continuing a terroristic campaign against militant pickets and radicals. Of the State’s 47,000 textile workers, at least 45,000 are out, silencing 133 plants. The “mopping up” process is a prelude to an attempt to re-open key mills under rings of bayonet steel.

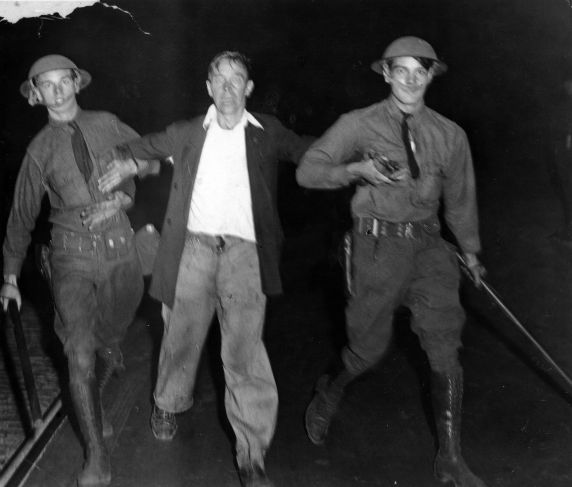

Ferrets, greedy for bribes, seek out all suspected of taking part in the Saylesville-Central Falls battle, which raged for three days and three nights with ten shot, one fatally, or at Woonsocket, scene of a ten-hour barricade fight where one youth was killed and three wounded. At least 25,000- men, women and children- were targets of tear and nausea gas in the two struggles.

Hundreds have been arrested in the three cities, where the streets are “No Man’s Lands” of barbed wire entanglements and machinegun nests. New seizures are reported hourly. Sixteen “known Reds” including John Weber, Providence Communist organizer, and Oreal Grossman, International Labor Defense attorney, are awaiting trials on Sept. 25. Numerous six-month sentences have been meted out, one to a boy for merely yelling “scab” in a non-martial zone.

First among the mills planning to re-open is the Sayles Finishing Company, dominated by Robert B. Dresser, State Republican boss, and scene of the first and last fighting. Another is the nearby Pawtucket plant of J. & P. Coats, R. I., Inc., of which Democratic Governor Theodore Francis Green is a leading stockholder and was formerly President. It closed Sept. 6 and later, forced most of its 31000 employes to petition the Governor for “protection from intimidation.” Largely English owned. Coats, through its affiliated American Thread Co., whose heavily guarded Willimantic, Conn., mills alone are operating, holds a world cotton thread monopoly.

Only a few small factories in Central Falls, Apponaug, West Warwick, Cranston and Bristol are running with skeleton staffs under National Guard martial law. Gov. Green conferred at the Newport yacht races with President Roosevelt, who previously had ordered regular troops to be held in readiness, and War Secretary Dern. As Rhode Island has only 2,000 National Guardsmen, all now on duty, there is great likelihood that Federal soldiers will be summoned.

Meanwhile, anti-Communist slanders pour from pulpit, press, radio and United Textile Workers Union misleaders Thomas McMahon, Francis J. Gorman and Horace Riviere, who are attempting to halt mass picketing. But 15,000 workers, marching on Sunday, Sept. 16, in a funeral procession through the Central Falls-Pawtucket factory district, broke an ominous silence to shout that they would be on hand weekdays to keep the mills closed.

As flying squadrons of pickets swept through the Blackstone River Valley, shutting one mile after another, two clashes occurred during the strike’s first week at the Sayles plant just north of the Moshassuck Cemetery. The largest rayon-treating firm in the trade, Sayles boasted that it had never been closed in any previous walk out. It announced that starting Monday, Sept. 10, a deadline would be established around its plant. The Republican mill barons gave their henchman, Jonathan Andrews, High Sheriff of Providence County, a rich harvest in special fees. He was paid a minimum of $12 for deputy sheriffs hired, permitted by law to pocket half of each fee and give the remaining $6 to G.0.P. ward heelers and gangsters. Food, lodging and entertainment were furnished free. There is no question that the new deputies provoked violence to win more blood money for themselves and additional cronies. Mill officials, hoping that martial law would break the State-wide strike, encouraged the blood lust. “The deputies were drunk,” a scarred veteran of the Moshassuck battle told me. “About 600 of us pickets began assembling on Lonsdale Avenue on Monday to halt the 3 o’clock afternoon shift from scabbing. State troopers hurled tear gas and began whacking us with long riot clubs. A few stones flew in self-defense. Some clubs were confiscated. Suddenly the wind shifted, blowing the fumes backwards. Then hell broke loose. At the filtration plant 20 deputies opened up with buckshot. Three fell wounded. The word spread and the crowd began to rally from all Central Falls.”

Five thousand swelled the workers’ ranks, battling far into the night. More than 25 are treated for injuries, including a striker with a fractured skull. A woman and two children topple unconscious in their nearby homes from gas. Meanwhile, the Governor mobilizes a skeleton regiment at a Providence armory.

Beginning early Tuesday morning, the picket line grows hourly on the bloody ground in front of the Filtration Plant. When the mid afternoon shifts change, 5,000 strikers, disregarding gas fumes, charge the Filtration Plant. The outer gate gives way and a small gate shack is overturned. As if surprised by its own daring, the crowd retreats voluntarily.

From the mill roofs, the deputies blaze riot guns, riddling three pickets including 75-yearold Mrs. Leonie Gussart. There are two more volleys of buckshot. Brig. Gen. Herbert R. Dean hurries to the mill with 280 members of Field and Coast Artillery companies on caissons. Armed with long billies, they club back the pickets, hurling tear and nausea grenades. Stones echo on steel helmets. A brick-loaded builder’s truck furnishes ammunition until troops capture it. Another volley and a fourth picket drops, shot in the head.

Strikers retreat into Moshassuck Cemetery, seeking shelter behind grave stones. At 6 p.m. the Governor mobilizes the entire National Guard, sending 220 more troops to Saylesville. The re-enforced guardsmen with fixed bayonets, enter the cemetery firing two more volleys. As a self-defense move, workers shatter street lights to mask women carrying off fighters unconscious from clubbings and gas. Autos are halted, being forced to dim lights or detour. All pickets captured are arrested. Meanwhile Gov. Green radios that his Guardsmen are not, firing shots and Joseph A. Sylvia, New England U. T. W. strike director, confers in the Sayles mill with Gen. Dean.

Under cover of darkness the workers advance on three fronts, stoning more street lights. Guardsmen send up illuminating flares, followed by gas bombs. In one sally, the workers seize twelve grenades. Shortly before midnight, 50 Guardsmen charge down Lonsdale Avenue but scamper back from a rock barrage. Although gas fumes reach the Woodlawn district, a mile away, workers hold possession of the graveyard until dawn when the Guardsmen’s ranks swell to 1,300. Wednesday morning only 200 scabs show up.

Holes are pickaxed in the pavement, corkscrew poles are erected and barbed wire is strung across all thoroughfares. At noon, according to an agreement between Gen. Dean and Organizer Sylvia, ten separate groups of ten pickets each, wearing white arm bands with black U. T. W. letters, pass inside the militia lines.

Outside the barbed wire entanglements a crowd gathers. Some climb into the cemetery, noting that only a couple of flat slabs are overturned. Suddenly a bayonet charge sweeps the burial grounds. In violation of the supposed truce, gas grenades curve there and into the street. Groups of accredited pickets retreat in confusion. Shouts of protest pierce the air. Young Charley Gorcynski, William Blackwood, father of two children, and Nicholas Gravello, stagger from bullets.

“The men,” said Gen. Dean, “went out with the intention of shooting anyone who did not obey orders. We have taken all we are going to take.”

Volley after volley rings out and the cemetery again is a battlefield. Fernand Labreche clutches a bloody chest. Inner tubes, hung between saplings, are catapults. Stones pelt barbed wire entanglements on a half dozen streets. But three days and nights have exhausted the workers.

Huge arc lights from the roof of the Woonsocket Rayon Co., subsidiary of the Manville-Jenckes mills, sweep searching rays into the darkened shambles of the Social Square business district. Every street light has been smashed and jagged plate glass rattles in department store windows. The white plumes of flare bombs hurled from behind an advancing ring of steel bayonets, etch out the bloody body of a youth sprawled in a gutter.

Wind spirals a cloud of tear and nausea gas above an overturned flivver, its shattered windshield painted, “Bargain, $20.” Two youths crawl out and start dragging an unconscious girl striker to safety. Rat-tat-tat! A new volley rings out. A boy staggers. A gas cloud blots him out. From a mill roof a white glow picks out a telephone pole with a white-haired French-Canadian behind, his arm curving a brick.. A shabby wooden store rains stones and. bottles. Throughout a two mile area the fighting rages and from all parts of this city of 43,000 workers recruits pour into a score of battlefronts, cheerfully braving death. Far back in the drab company houses districts spreads the rallying cry, “On to the rayon plant. They shot down our pickets. Gov. Green’s truce means bullets.” Gas-raw throats repeat it in French, Polish and Portuguese.

The battle, in which 15,000 workers defended themselves by erecting street barricades to hold back three companies of National Guards, police and mill thugs, raged for ten hours, from Sept. 12 to dawn the following day. Jude Courtemanche, 19, brother of a nun, was killed by a .38 calibre police slug, although newspapers tried to blame the murder on “the hordes of destruction loot crazed rioters,” citing that the Guardsmen used .45 calibre bullets, and three others were probably fatally injured by militia rifle-fire. Stores suffered $16,000 in damage.

The fighting started when assembling pickets tried to free an arrested striker and cops blazed away with pistols. They had been dispersed, vomiting and blinded by fumes on Tuesday at midnight, second day of the three-day Saylesville battle. Monday morning had seen 4,000 Woonsocket members of the Independent Textile Workers Union walk out, in a city that previously had completely defied the general strike.

Residing just south of the Massachusetts border, the Woonsocket militants promised to close down 48 mills and then move on to Lawrence where the independent union is the main organized labor body. Since the heroic battle, barbed wire circles the mill and business districts, 1,700 troops are on duty and a 6 p.m. curfew closed all downtown stores, theatres, dance halls, saloons and pool rooms for three nights.

Even now in some quarters, Theodore Francis Green is termed a non-partisan liberal. He attacked gun-toting deputies; Sheriff Andrews is a Republican. He denounced “reactionary mill owners” and dismissed Gen. Everitte St. J. Chaffee, State Police Commissioner. The Republican general was replaced by Edward Kelly, a Democrat.

Before the textile strike the liberal Governor named Francis J. Gorman, U. T. W. Vice President and now national strike leader, as Rhode Island State Labor Commissioner only to have his appointee spurned by Senate Republicans. A wealthy textile magnate by inheritance, this friend of labor never permitted unionization of workers while he was president of the Coats thread monopoly. That’s a Coats’ policy in both England and America.

On September 11, Coats presented a petition with “signatures” of 97 percent of its employes to the Governor. That day, the great liberal mobilized the National Guard. Green, on Sept. 12, publicly assured Kenneth D. MacColl, treasurer of Coats, that he is “exerting every possible effort to suppress disorder so that 2,738 Coats workers who petitioned for protection may return to work and earn wages without molestation.”

A politician seeking re-election-he was swept in on the Roosevelt tide in 1932- Green tries every method to curry votes. An Agawam Hunt Club snob, he nevertheless goes on campaign tours speaking French, Italian and Polish. Before the first pitched battle on Sept. 10, he attempted unsuccessfully to raise the Red scare in a radio address. Newspapers went to his aid on Sept. 12 when nine Boston furniture workers were arrested outside a Providence upholstery plant. Needing a shield for spilt blood, at 9 a. m., Sept. 13, with all fighting ended, the Governor ordered the immediate arrest of every known Communist in the State. “This is a Communist uprising, not a textile strike,” he told the General Assembly later in the day. U. T. W. Organizer Sylviar instructed each local to aid police in “driving Communists not only from the strike areas but from the State.”

Because he went to the Providence police headquarters to defend imprisoned workers on the day the Communist Party was outlawed, Oreal Grossman, I. L. D. attorney, was held incommunicado for 36 hours. Finally, suffering from a severe cold contracted in a damp jail cell, he was released under bail on a flimsy lottery charge. He possessed a banquet ticket that might entitle him to a free trip to the Soviet Union. An energetic, black-haired Rhode Islander, Grossman was horn in Providence 33 years ago. His law office is in a clapboard home above a Pawtucket store and under the shadows of rayon mills. Learning of the outlaw edict, he hurried to the second-story office at 447 Westminster Street, Providence, to find that truckloads of “Dailies” and Party literature had been carted away. The walls had been stripped and cops were beginning to nail the doors. The flatfeet were hesitant about arresting a lawyer.

As cops can hold prisoners for 24 hours without a charge, Grossman went home for supper and then sought out police headquarters at 9 p.m. Detective Captain Francis Barnes hauled him into an inner room and barked questions: “Do you believe in violence? Did you write this leaflet inciting to riot? (The mimeograph called for “a determined, orderly march” to the State House to protest troop terrorism and demand funds for the wounded.) Were you at Saylesville? Have you got a gun? Are you a Communist?”

“Don’t use the word loosely,” Grossman replied. “If you mean am I a member of the Communist Party- No; if you mean do I accept the economic teachings of Karl Marx- Yes.”

“You’re a known Communist,” shrieked Barnes. “Take him down and put him in the cooler.”

“They took away my belt and tie and left me with only a single handkerchief,” Grossman told me. “Fifteen of us were herded into a detention pen, twenty by thirty feet. Bugs ran across the floor. Hard wooden benches without cushions surrounded the walls. All night the comrades were cooped up there, unable to sleep. A single unsanitary toilet could only be flushed by an outside guard. There was no running water. In the morning, over my protests, we were fingerprinted and mugged without being charged with a crime. I was barred from phoning a lawyer. At noon we were grilled one at a time. I faced Clifton Munroe, Counsel of the Public Safety Commission. Police Lieut. Goodman, of the Boston Radical Squad; Immigration Inspector William S. Clarke and others. Back to the pen again until night when I was transferred to a damp steel cell with Joseph Pianka, an artist suffering from hay fever. The next morning, Saturday, I was taken handcuffed to court. Other comrades were shunted from local to State Police for a second 24 hours. Not until Sunday were some freed and then under bail as high as $1,000 on charges of being idle persons. But we got them out and we’ll get others out.”

Inside a weather-beaten clapboard house in Central Falls, a gnarled Polish mother, a stoop-shouldered father, five sisters and three little brothers sob over a white coffin. Charley Gorcynski, 18, and their sole support until he went on strike at the Guyan Mills, is dead, shot in the stomach during a supposed truce at Moshassuck Cemetery.

Outside, two single lines of bareheaded men, scarred veterans of gas barrages, bayonets and three days of rifle fire, shuffle slowly up narrow High Street, hugging close to opposite gutters. Banking the sidewalks ten tiers deep are their women and children, mainly swarthy, high-cheeked Poles. A single policeman, a pot-bellied old fellow with a warty neck, leads the procession. Only in the distance are there other cops and they are directing traffic. Today, police avoid this dismal slum.

North of Pulaski Court, at St. Joseph’s Polish Catholic Church, they halt. High in the haughty brick and concrete tower the chimes begin and they peal metallically and wearingly. Between the lines, puffs a flowerbanked flivver, a gold-cassocked priest, three assistants and the white hearse. The casket is carried inside but only women and children enter the church. These weavers and loom fixers, with better ways to mourn their fellow worker, turn into Roosevelt Street and, four abreast, trudge towards the Central Avenue factory district. Suddenly, with the abruptness of a burst bomb, ten thousand throats explode.

“We’ll be here to-morrow. We’ll keep these mills closed.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v12n13-sep-25-1934-NM.pdf