‘Conscientious Objectors in America’ by Norman Thomas from The American Labor Year Book 1919-20, edited by Alexander Trachtenberg. The Department of Labor Research, Rand School of Social Science. New York, 1920.

In the broadest sense of the term, the conscientious objector is the man who refused to bear arms because his convictions were opposed either to all wars or to this particular war. The number of objectors, according to the official statement of the War Department issued June 18, 1919, is small. Only 3,989 claimed exemption at camp.(1) To this must be added the unknown but considerable number of men who refused to register and were for this offense sentenced to civil prisons for terms which by law could not exceed one year. An unknown but considerable number of such prisoners are still in confinement. Members of this group, on completion of their civil sentences, were automatically enrolled as soldiers, and so became subject to military law. Hence it came to pass that certain men suffered severely both in civil and in military prisons. The War Department statement classifies objectors as follows:

Originally accepted or were assigned to non-combatant service- 1300.

Furloughed to agriculture-1200.

Furloughed to Friends’ Reconstruction Unit, France- 99.

Remaining in camp after the armistice- 940.

General court-martial prisoners- 450.

Total- 3989.

This classification can only be explained by summarizing the history of the treatment of objectors.

By the terms of the selective service law exemption was granted from combatant service to bona fide members of religious sects or organizations whose creed or principles were opposed to war. This attempt to make conscience a corporate and sectarian matter was of course both illogical and unjust, and to the credit of the Quakers, who were the principal religious body to be benefited, it must be stated that they protested against this kind of favoritism. The President, by virtue of his powers as Commander-in-chief of the army and navy, granted more liberal terms to the objectors. Actually the history of conscientious objectors in the war was somewhat as follows: The extraordinary power of social pressure brought it to pass that comparatively few men had the courage to persist in the policy of conscientious objection which, at the beginning of the war, thousands of men had declared they would embrace. At the camp both persuasion and threats were more or less cleverly used to break down the courage of men who at first thought they were going to be conscientious objectors. Those who persisted in their refusal to accept combatant service were usually offered non-combatant service, which in practice was very easy to procure if a man were able to satisfy his conscience simply by personal abstention from killing while remaining an integral part of the military machine. About 1,000 men accepted this type of service at camp without examination by the special board of inquiry which was ultimately set up for the benefit of the more obdurate objectors. Men whose objection to war and to conscription for it was such that they could not accept noncombatant service were segregated in camps under conditions inevitably provocative of friction. In many cases they suffered severe brutality at the hands of intolerant officers, contrary to the War Department’s orders. The War Department, which in general proved utterly incompetent to deal with atrocities in military camps and prisons, was not very effective in enforcing its own orders in behalf of conscientious objectors.

The Board of Inquiry

On June 1, 1918, the President issued an order which permitted the furloughing of conscientious objectors for agricultural service or in connection with the Friend’s Reconstruction Unit in France. To determine the “sincerity” of the objectors a board of inquiry was set up, consisting of Major Richard C. Stoddard, Chairman, (later succeeded by Major Walter G. Kellogg); Judge Julian W. Mack, of the United States Circuit Court; and Dean Harland F. Stone, of Columbia University Law School. This presidential order of June 1, modified by more comprehensive instructions June 10 and July 30, constituted the basis of further proceedings. The statistical results of the work of the Board of Inquiry have already been given. As a result of this work the furloughs already enumerated were granted to conscientious objectors. It remains to explain the court-martial sentences. The statistics of court-martials are as follows:

Tried by court-martial- 104.

Acquitted- 1.

Convicted and sentenced- 503.

Disapproved by higher authority- 53.

Effective sentences- 450.

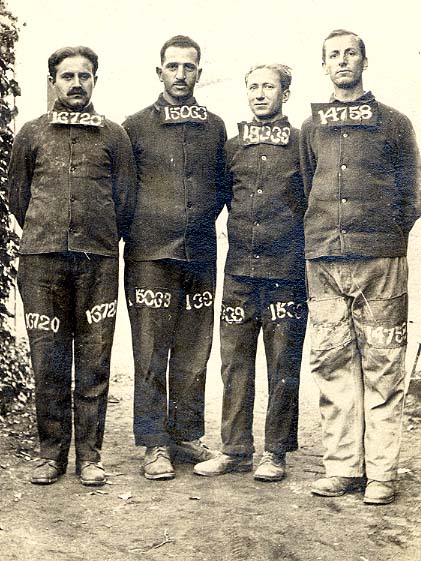

These 450 men received ferocious sentences running from ten to thirty years. They were composed —

Analysis of Court-martialed Objectors

(a) Of men who had been court-martialed by impatient officers, contrary to the letter and spirit of the War Department’s order, before the appointment of the Board of Inquiry.

(b) Men ultimately court-martialed despite the fact that the Board of Inquiry had granted them the privilege of receiving a furlough for agricultural work, which however, owing to imperfections in departmental machinery they never actually received. In the meantime these men and others had been confined in the army camp at Fort Riley, from which some of them later were transferred to Camp Funston, which adjoins Fort Riley. At these two army posts some of the worst atrocities took place. Men whose sincerity had already been acknowledged by the Board of Inquiry were subjected to all manner of brutality and persecution, and were ultimately court-martialed, not for being conscientious objectors, but for having refused some petty order, as for example, to clean up camp — a, refusal made by the men in accordance with their logical determination not to be subjected to military authority.

(c) Among those ultimately court-martialed after severe persecution was a group classified by the Board of Inquiry as “insincere” and therefore not eligible for furlough, who proved their sincerity by their steadfast endurance under most trying circumstances. As a result of it two army officers were dismissed from the service, and have spent their time since in maligning the objectors. In justice to the Board of Inquiry it should be explained that in deciding that an objector was “insincere” they usually meant that his objection was only to this war — not to all wars, an illogical and unjustifiable differentiation which the War Department compelled them to make.

(d) The final group of court-martialed objectors consisted of those who on principle refused to accept any form of alternative service whether on farms or in France because such service recognized the right of the State to conscript men against their conscience. These men are commonly called absolutists. They felt that their highest service was to protest against conscription, and that that protest would never be effective so long as the issue was avoided by the acceptance of alternative service however good such service might be in itself.

On January 17, 1917, 113 of the court-martialed conscientious objectors then confined in Fort Leavenworth were discharged because they should never have been given court-martial sentences, under the War Department’s own ruling, i.e., they belonged to class (a) in the grouping we have given. Owing to army red tape they received back pay, which has been made the subject of attack on them and on the War Department in all the jingo papers. As a matter of fact the objectors voluntarily refunded this money in excess of travelling expenses, to which they were entitled. In all, a total of $9,840.55 was thus returned. This is exclusive of large amounts paid by conscientious objectors who accepted alternate or non-combatant service, to the Friend’s Reconstruction Unit and the Red Cross.

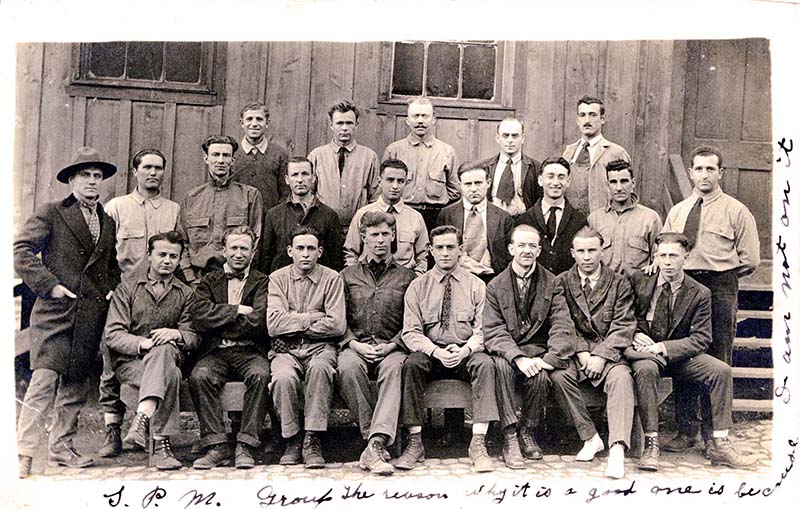

Conscientious objectors varied widely in education, background, and reasons for objecting. The large majority of them were members of religious sects opposed to war. The more intelligent and aggressive, generally speaking, were intellectual radicals. Socialists, philosophical anarchists and the like. Many of these of course also had religious objections to war.

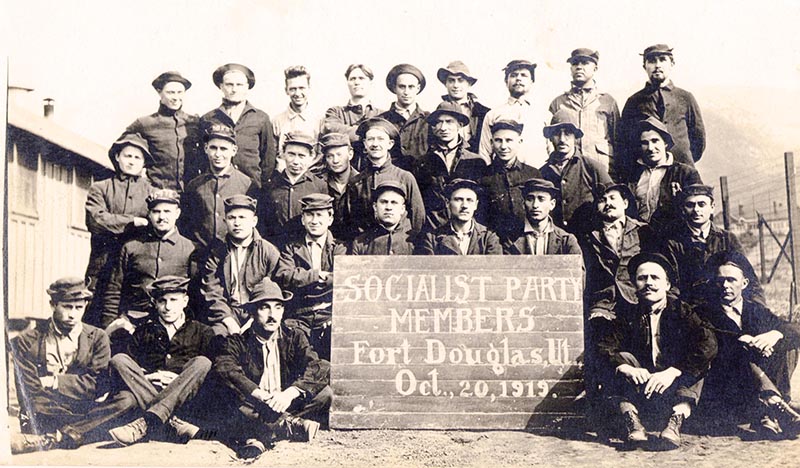

The public wrath at the disclosures of the injustice of the court-martial sentences in the United States forced a general reduction of sentences, from which conscientious objectors benefited. The War Department has moreover tried to evade the whole issue of conscientious objection by quietly “losing” one objector after another by pardoning him or discovering that something or other was irregular about his sentence, so that at the present time (August 12, 1919) the number of objectors still in confinement is probably only about 250, of whom 121 are still in an internment camp at Fort Douglas, Utah, to which most conscientious objectors were recently transferred; about 20 are at the military prison at Alcatraz Island, San Francisco Bay; the rest are probably still at Leavenworth.

- In at least two cases that have become known, perhaps also in many others, conscientious objectors were taken to France as combatant soldiers.

Rand School of Social Science was founded in 1906 by supporters of the Socialist Party of America in New York City. A worker educations school, in addition to classes a publishing house, research institute, as well as camps and retreats were developed. The school came under the Social Democratic Federation after the split in the Socialist Party in 1936 and changed its name to the “Tamiment Institute and Library” with Its collection forming the basis the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives at New York University.

PDF of book: https://archive.org/download/americanlaborye00sciegoog/americanlaborye00sciegoog.pdf