The more I read from S.J. Rutgers, the more impressive he becomes. This article appeared in the Socialist Propaganda Leagues’ ‘New International,’ a journal edited by Louis Fraina and inspired by a January, 1917 meeting in New York attended by, among others, Nikolai Bukharin, Alexandra Kollontai, and Leon Trotsky, and is another stimulating reflection as comrade Rutgers continued to define the new politics of the emerging Left Wing in U.S. Socialism. This outing sees Rutgers contemplate Rosa Luxemburg’s ideas on ‘Mass Action’ in light of the year of revolutions and repression that was 1917.

‘Mass Action and Socialism’ by S.J. Rutgers from New International. Vol. 1 No. 10. February, 1918.

ROSA LUXEMBURG has called the mass strike the dynamic method of the proletarian struggle in the Revolution. She considers mass action and its most important feature the mass strike, as the sum total of a period in the class struggle that may last for years or tens of years until victory comes to the proletariat. In permanent change, it comprises all the phases of the political and economic struggle, all phases of the Revolution. Mass action in its highest form of political strike means the unity of political and economic action, means the proletarian revolution as a historic process,

The word “mass action” like the words “class struggle,” “industrial action,” “Imperialism,” etc., may mean nothing; in fact they are used to cover the most conflicting thoughts and deeds. Representing a general conception living in the minds and the deeds of millions of workers, a word may become a powerful symbol and active force in the struggle for emancipation. Since Capitalism is outgrown and has to maintain its grasp on the world by mental and moral fraud, a clear conception of proletarian methods is most essential. Science being the monopoly of non-proletarian classes under Capitalism, all the workers can hope for, unless they will entrust their fate into the hands and heads of middle class representatives, is to grasp some of the fundamental proletarian truths. These truths inevitably have to be coined into short slogans, this being the only form of theoretical abstraction, suitable both for the purpose of proletarian theory and fighting practice. What a “thesis” means to the scientist is expressed by the workers in general slogans and expressions, such as mass action, Imperialism, industrial unionism, class struggle, etc. Such and similar words may be said to express the proletarian philosophy, the strength of which depends upon the completeness and the unity of conception reflected by these words in the minds of the workers. The meaning of the words changes with the position of the workers in the class struggle and together with the consolidation of tactics, the corresponding conceptions get a more definite and more general shape. But at the same time the consolidation of these conceptions in the heads of the workers result in a more efficient, a more powerful struggle for emancipation.

Conservative Socialists may call any meeting of a dozen persons or over, a mass meeting, and may consider a big middle class vote the highest form of mass action- there is little doubt, however, that in large and increasing groups of American workers the idea of revolutionary mass action grows into a living and powerful conception. Industrial action, no doubt, forms the backbone of the conception in a country with highly developed industry. Industrial Unionism may, however, develop into a struggle for wages only; into job control without any further vision. Mass action is the broader vision, which includes all mass movements towards the Social Revolution.

It may be objected that, if industrial action is the most efficient form of mass action, why bother about minor issues? Why not concentrate all our efforts and thought in building our industrial unions so strong as to overcome the capitalist employer and the capitalist state? Such an objection overlooks the complexity of real conditions. We are not free in choosing our methods in accordance with certain general theoretical constructions, but have to build on the solid ground of actual facts in the light of historical developments. No matter what our preachings mass movements in one form or another will develop and we will have to make the best of it. And on the other hand, industrial organization has its historical limits beyond which we cannot rise at the given moment of our action. Large groups of workers will continue for a certain length of time to organize in craft unions, and although we will tell them they are wrong and fight them where injurious to their class, still they will be a factor in our revolutionary struggle either for or against. Moreover large groups of unskilled workers will continue to live in such a state of slavery and terrorism, that only occasional shocks will be able to overcome the pressure of the iron heel. We also have to bear in mind that the very process of capitalism consists in swallowing middle class groups and farmers between the grinding wheels of industry and that each generation needs again its education towards industrial action, and at any given moment millions and millions of proletarians will continue to work under conditions very remote from big industry, and though it may be true that these groups never will be the backbone of revolutionary movements, still they will have to play their part. To overcome the capitalist organization and the capitalist state is a job in which we cannot afford to neglect whatever forces may contribute to success. We are not satisfied to wait until in some problematic future all capitalist production will be in the form of big industry and all proletarians will have passed the school of industrial education. We are convinced that the technical development of the capitalist world makes conditions ripe for a Socialist commonwealth at this very moment, that only our lack of power stands in the way of the realization of our hopes. What we want above all is a unity and concentration of the forces already existing in a latent form, a combination and further development of these· forces towards our revolutionary aims.

The mental expression of this unity of proletarian forces is “mass action.” It is the expression of the firm belief that the workers can only count on their own power. It means a definite break with the diplomacy, corruption and betrayal of middle class leaders. It calls for a clear-cut, straight-lined class struggle theory and tactics, not only within the mental grasp of the average worker, but in such a form that the mechanism of its organized expression can be carried on by the workers without being dependent upon high-brow intellectuals. Mass action appeals to the numbers, but numbers welded into a mass, numbers bound together by a common cause, a common aim, a common thought, leading to common action and common organization. In its complexity of form, mass action mirrors the actual variety of the working class, in its unity of action it throws aside all middle class elements, that are not willing to break with their capitalist affiliations. Mass action is the very horror of the small bourgeois minds; is mere craziness to the intellectual radical. How in the world should the poor uneducated worker get along without the well meaning, costly advice and representation of intellectuals?

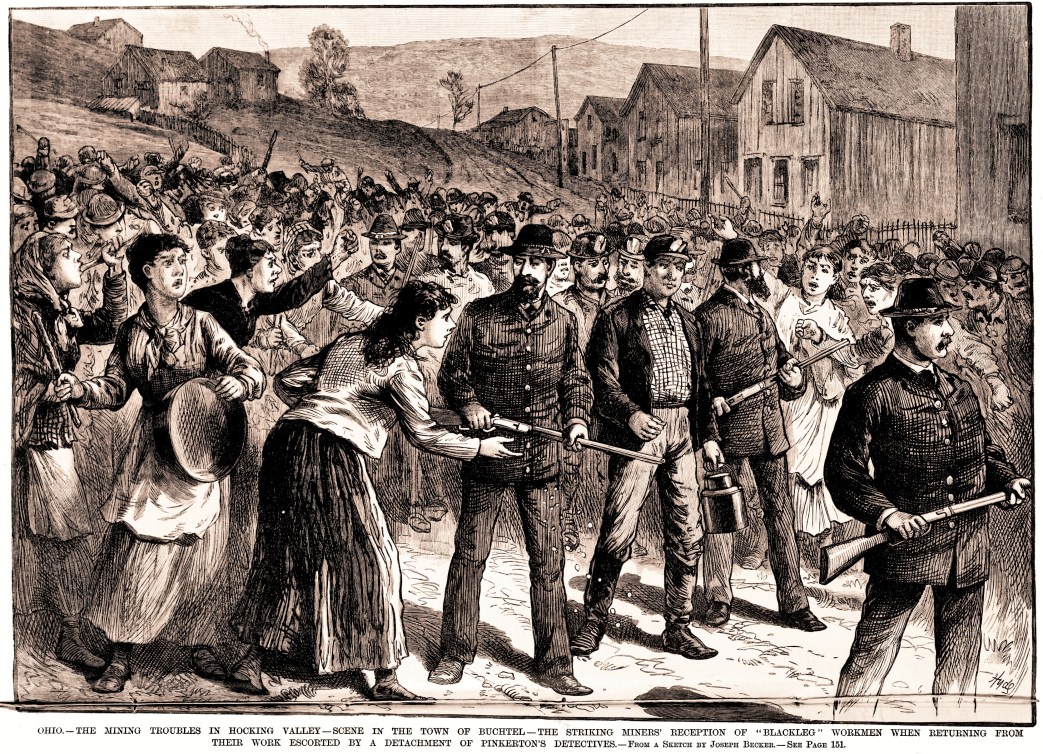

But is it possible to increase our power by street demonstrations; strikes of protest, general campaigns for political issues, such as freedom of speech, judicial murders, militarism, high cost of living, unemployment, etc.? Are not the masses who come together for those purposes too heterogeneous, too much liable to be dispersed or annihilated by military force, too unorganized to develop power? To answer this question, we should first realize what the purpose is of our power. We want power for the Social Revolution to overcome capitalist society. You may overcome power by strengthening your own, as well as by weakening your opponent’s power. A wrestler may subdue his colleague by a supreme effort, but he will more likely succeed because his opponent tires out quicker. Mass demonstrations may not be able to force a government to give in, but there is no doubt that mass demonstrations,. Strikes of protest, etc., have a strong tendency to weaken the position of the capitalist state. Demonstrations can and will be suppressed by military force, but this at the same time endangers the morale of militarism itself. Even the New York police showed signs of discontent and revolt, on account of the demonstrations in connection with the recent car strike. In a period of numerous demonstrations and protests all over the country combined with a variety of strikes, the bureaucratic apparatus will have great difficulty in maintaining its regular efficiency. At the same time the government will, through concessions in some places and brutality in others, open the eyes of large groups of workers previously caught in bourgeois ideologies of a State for the benefit of “the People,” etc. And we should not forget that education through mass action is one of the most important factors to increase our power. No education without action and no greater educator for the workers than mass action. We should not overlook the fact that mass demonstrations will include the well trained industrial workers, will go hand in hand with strikes, and to a certain extent can be organized in accordance with each special occasion, which is one of the foremost duties of a revolutionary Socialist party.

An advantage of demonstrations in connection with problems is that they put a general issue for immediate consideration, and thereby tend to concentrate and unite action, in which industrial strikes may be supplemented by other mass movements involving the capitalist state in a general fight from which it can only escape either by concessions or by brutality, in both instances opening the eyes of new groups of proletarians.

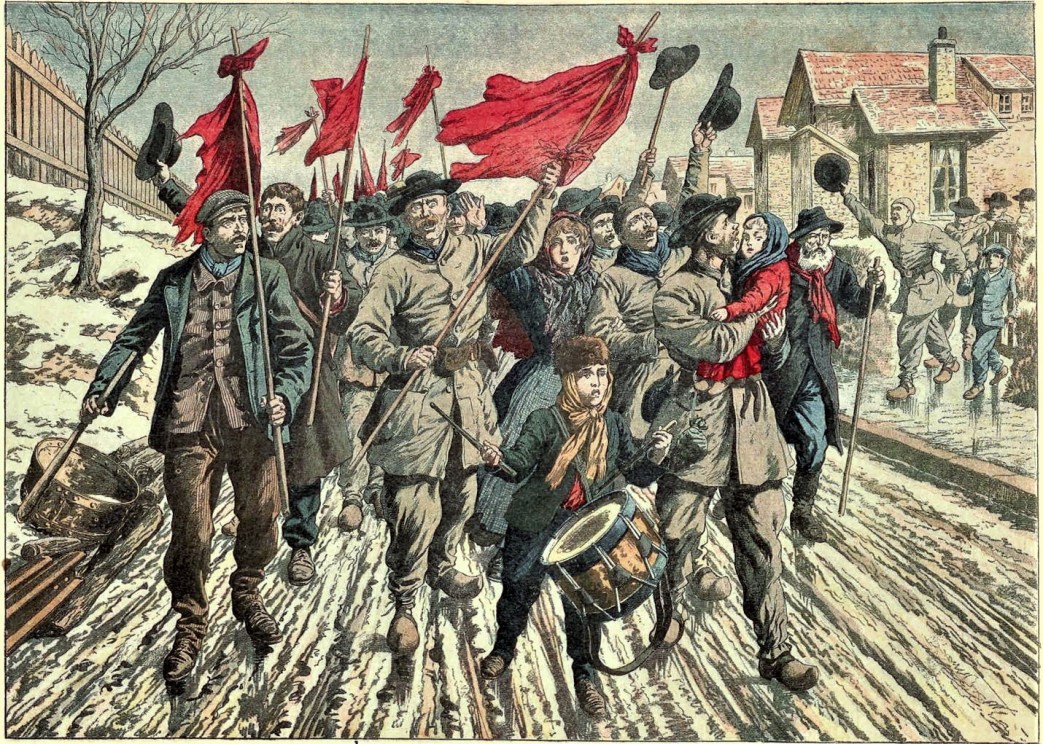

Mass action never can be antagonistic towards industrial action, because the latter is only the most efficient form of mass action, is a part, is the backbone of general mass action. No successful mass action is conceivable without being firmly rooted in the economic power of the workers, and the strongest form to organize this power is in industrial unions. But this does not mean that there is no economic power outside of this particular form of organization. In fact industrial unions at present are surprisingly weak. Is it logical, is it less than a crime to neglect all other forms of economic power of the workers so far as they can be utilized for the big fight against Capital and the capitalist state as its most formidable instrument? Will the Russian revolution with its splendid unity of industrial strikes and street demonstrations into one sweeping mass movement have no lessons for us?

Will we wait for certain forms where others act and win? Would the German workers have a chance unless they combine industrial strikes with more general forms of mass action?

New International was the paper of the Socialist Propaganda League of America begun in Boston as ‘The Internationalist’ at the start of January 1917 and first edited by John D. Williams who had started an early correspondence with Lenin. The SPLA was the US reflection of the Zimmerwald movement of internationalist Socialists during World War One that became the basis for the Third International after the Bolshevik Revolution and New International became its voice. On January 16, 1917 a meeting was held in Brooklyn attended by Leon Trotsky, Nicolai Bukharin, Alexandra Kollontay, V. Volodarsky, and Grigory Chudnovsky and the SPLA to discuss the International. The paper then changed its name to New International with Fraina as editor. The paper lasted only about a year before Fraina began publishing Revolutionary Age.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-international/v1n10-feb-1918-ni.pdf