Pioneering Marxist movie critic Harry Alan Potamkin reviews German director G. W. Pabsts’ 1930 film Westfront 1918 (here titled Comrades of 1918), and his 1931 Kameradschaft (Comradeship), tracing his evolution as an artist, and wonders if such films are possible in the United States.

‘Movies and Revolution’ by Harry Alan Potamkin from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 5. December, 1932.

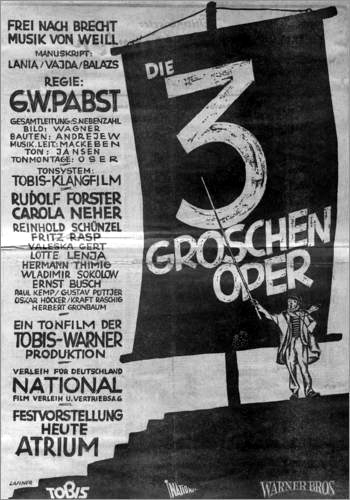

Comrades of 1918, a sensitive and intense motion picture of men marshalled, maimed, and murdered in war, never heroic, was G. W. Pabst’s entrance into the film of speech and sound. Heretofore he had been a cult of the effete, with peripheral, polished “case studies” in “phobias” and “complexes.” That was his Viennese, petty-bourgeois development. The intensifying class-struggle, forcing intellectuals of sensitiveness beyond indulgence and “beyond desire,” impressed itself into the consciousness of Pabst. He had seen, at that acute moment, Dreyer’s Joan of Arc, and had defended that profound film against his own cultists’ objections. This middle-class fear of maximum, its own maximum, is a phenomenon that exposes the retrogression of that class, vitiated but tenacious. At that moment too came a new sensory element into the cinema and that was encouragement and a fresh opportunity. His conscience stirred, Pabst’s talents have realized themselves in a consistent growth from the pacifist war-film through the majestic Die Dreigroschenoper to Kameradschaft.

In 1906 French miners were entombed at Courrieres on the Franco-German border. The Germans came to their rescue. That event of class-solidarity is the core of Comradeship. But with correct insight into the political import of the event, Pabst and his scenarist Vajda project the occurrence into post-war Europe, 1919…A fire has been raging in the French sector of the mine. French Courrieres is encased in the ominousness of that fire…Three German miners visit a cafe in the French town. One of them asks a girl for a dance. She refuses. He says the Germans are as good dancers as the French. Threatening faces collect. The Germans leave. “Why did you refuse to dance with him?” asks the girl’s sweetheart. “I’m tired,” she answers…Into the French sector the miners go, also the fire-fighters. The girl leaves for Paris; she cannot endure the doom immanent village…A grandfather fearfully escorts little Georges to his first decent into the dragon’s mouth…The mine caves in. The girl leaps from the train at the next village, returns to her home. Her brother and lover are among the fire-fighters. The village assails the mine-gates.

In the German sector, men are going off-shift. A nucleus decides to go to the aid of the French miners. Some of the Germans are hostile to the idea, remembering 1918, thinking of their own families. But the nucleus is magnetic. It asks the management for the rescue-equipment. The free hours are given to comradeship.

In motor-trucks the rescuers depart. They cannot wait for passports and visas; they cannot stop to explain at the frontiers. They rush through the arbitrary border-line; a too-dutiful flunkey shoots. The symbol is real. However, the German management has advised the French of the departure of the rescuers; the frontier-guard is told. “Thank you for your kindness,” says the French operator. “Not at all,” replies the German. The risks of capital…

Meanwhile the three German buddies of the escapade in the French cafe have gone on-shift. Their leading spirit, who recalls that in the war the mine was a road into the French territory, rushes to the mine-wall where “the frontier goes 800 meters down.” His companions follow him. They hack their way into the French sector. They come upon the grandfather who has found his Georges after an anguished search. The seams have broken. Water floods in. The men hack their way into the engine-room and stables. Entombment threatens them there. But they are rescued by a telephone ring…

The rescue is done directorially with a fidelity to fact and with a devotion to the human content of the episode and thereby achieves an importance greater than the single incident. Pabst has said this film is “ethical.” Its artistry is the complete submission of the technique — camera, set, lighting — and almost complete submission of the acting to this “ethical” intention. No longer is Pabst smooth-finishing surfaces, calling the ambiguous subtle or playing Jack Horner. The denouement of the film, when the Germans have been released from the hospital, is poignant and hopeful. At the frontier the French fire-fighter, the girl’s brother, says “We workers are one! and our enemies we have in common; Gas and War!” The German who was refused the dance embraces the girl. A German rescuer speaks: I have not understood the French comrade’s words, but their meaning I have felt.

And here we ask for a further declaration. We ask, indeed, that the entire film be pitched to a completer attack, that its explicit condemnation of national barriers, cleavage of working-class unity, and its urging to unity be pointed to a sharp statement as to who is the enemy, who really is this Gas-and-War. Yet we should be naive or sectarian critics indeed did we not recognize this film as a maximum within the present network of film-control. And what has made this maximum possible? First, the high level of the revolutionary movement in Germany. Second the producing company, Nero, is not within the dominant sphere of action centered in the U.F.A. of Hugenberg, the Nationalist leader. Third, a director of social conscience, responsive, in measure, to the first determinant, was in charge of the operations. It is worth mentioning that his scenarist has been previously accustomed to intrigues like those of Molnar, the Buda pest. Change the determinants and you change the determination. It is also worth considering whether Pabst will hold out or be sustained at the level of Comradeship, He has since made L’ Atlantide, based on the hokum-novel by Pierre Benoit, the French Rider Haggard, and has been recruited to do Don Quixote in England. We might anticipate the latter were we not suspicious of Chaliapin as the Spanish windmill-warrior — will we have the grand satire of Cervantes or merely an upholstered opera?

To us here, Comradeship places again the question: is it possible to create a proletarian cinema in capitalist America? It is true that of all the media, excepting the radio, the movie is the severest in its resistance. This is due to the nature of the film, the complications involved in making pictures, the expense of making films and the monopoly vested in Hollywood, Hays and Wall Street. Yet, recognizing the severity of the resistance, we know, not solely by an instance like Comradeship which is, after all not quite the American case, but by our own evidences mainly, that resistance can be overcome. The Workers’ Film and Photo League now extends to several cities; audiences have been established through workers’ clubs and mass movie-meetings; the Soviet films have created a critically receptive body of spectators. Slowly but with increasing assurance the movie-makers of the Workers’ Film and Photo League have been improving the sense of selection and their skill in the documentations they have made. The record by the Los Angeles section of this League, of the “Free Mooney” run across the Olympic stadium is one of the finest of dramatic newsreel-clips I have seen. Such data will never appear in the commercial release.

The sense of selection has still to be educated in the political references of an image and its combination with other images. Certain bad influences or wrong readings from, respectively, the American newsreel or the Soviet kino have to be yielded. And, of course, constant training in technology and its application is essential. Yet, in these first efforts of the Workers’ Film a Photo League there is the one potential’ source for an authentic American cinema. Other groups, amateur or “independent,” are frivolous or merely nominal. The League is motivated within the strongest contemporary force, the revolutionary working-class, is self- critical, eager and, as a unit, suspicious of egotisms. The time is perhaps a long way off when it can produce enacted dramatic films. The German proletarian film-makers ventured into such enterprises and issued either a duplicate of the simplistic “strasse” film or lugubrious episodic linkages of a period when the German proletariat were more “pathetic” than proud, a period exemplified in the graphic art by Zille. When our comrades of the League are prepared for the dramatic re-enactment, a film like Kameradschaft will not be a bad pattern. But even now, in this period of the record, the Pabst film is instructive: it is a record a restoration that achieves partial revelation.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1932/v08n05-dec-1932-New-Masses.pdf