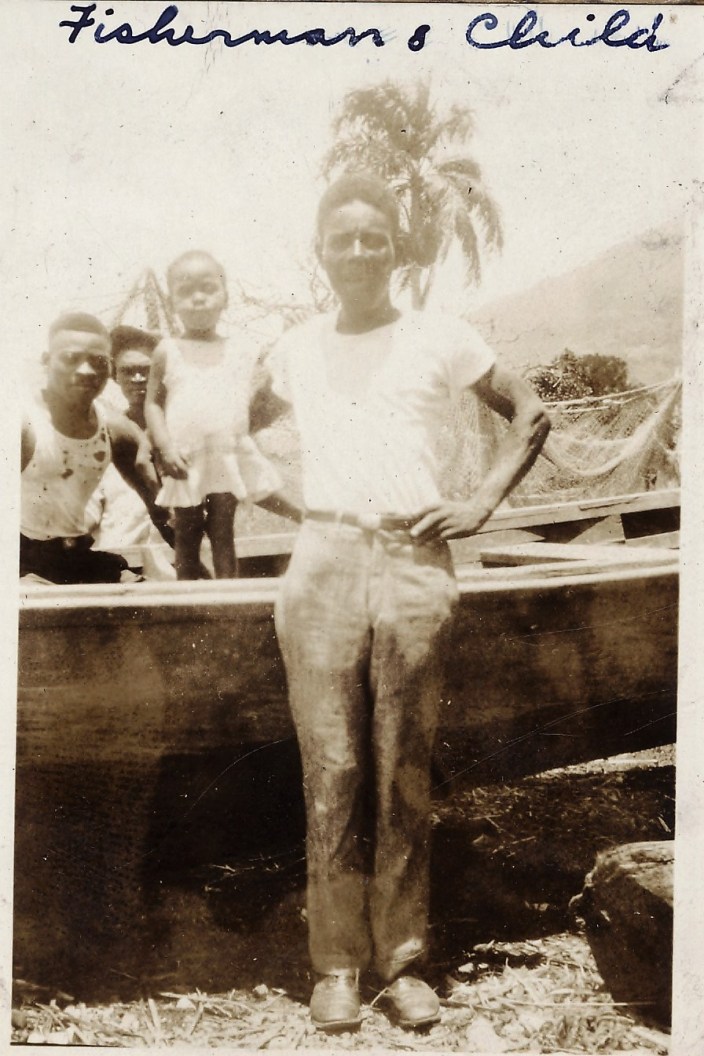

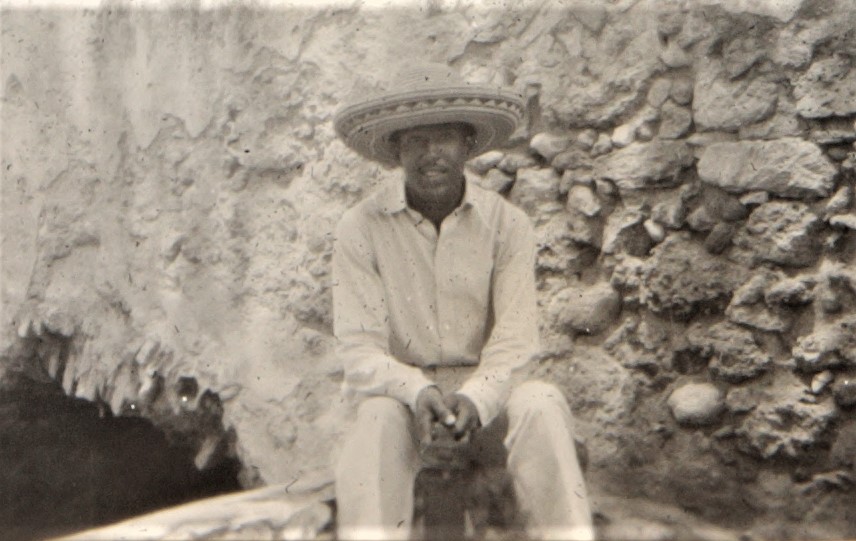

In 1931 Langston Hughes visited Haiti under U.S. occupation as part of a larger journey through the Caribbean and sent back this report to the New Masses. Photos are from Hughes’ own scrapbook of his trip.

‘Haiti: A People Without Shoes’ by Langston Hughes from New Masses. Vol. 7 No. 5. October, 1931.

Haiti is a land of people without shoes — black people, whose bare feet tread the dusty roads to market in the early morning, or pat softly on the bare floors of hotels, serving foreign guests. These barefooted ones care for the rice and cane fields under the hot sun. They climb high mountains picking coffee beans, and wade through surf to fishing boats in the blue sea. All of the work that keeps Haiti alive, pays for the American Occupation, and enriches foreign traders — that vast and basic work — is done there by Negroes without shoes.

Yet shoes are things of great importance in Haiti. Everyone of any social or business position must wear them. To be seen in the streets barefooted marks one as low-caste person of no standing in the community. Coats, too, are of an importance equal to footwear. In a country where the climate would permit everybody to go naked with ease, officials, professional men, clerks, and teachers swelter in dignity with coats buttoned about their bellies on the hottest days.

Strange, bourgeois, and a little pathetic is this accent on clothes and shoes in an undeveloped land where the average wage is thirty cents a day, and where the sun blazes like fury. It is something carried over, perhaps, from the white masters who wore coats and shoes long ago, and then had force and power; or something remembered, maybe, as infinitely desirable — like leisure and rest and freedom. But articles of clothing for the black masses in Haiti are not cheap. Cloth is imported, as are most of the shoes. Taxes are high, jobs are scarce, wages are low, so the doubtful step upward to the dignity of leather between one’s feet and the earth, and a coat between one’s body and the sun, is a step not easily to be achieved in this island of the Caribbean.

Practically all business there is in the hands of white foreigners, so one must buy one’s shoes from a Frenchman or a Syrian who pays as little money as possible back into Haitian hands. Imports and exports are in charge of foreigners, too, German often, or American, or Italian. Haiti has no foreign credit, no steamships, few commercial representatives abroad. And the government, Occupation controlled, puts a tax on almost everything. There are no factories of any consequence in the land, and what few there are largely under non-Haitian control. Every ship brings loads of imported goods from the white countries. Even Haitian postage stamps are made abroad. The laws are dictated from Washington. American controllers count their money. And the military Occupation extracts fat salaries for its own civilian experts and officials.

What then, pray, have the dignified native citizens with shoes been doing all the while those Haitians, mulattoes largely, who have dominated the politics of the country for decades, and who have drawn almost as sharp a class line between themselves and their shoeless black brothers as have the Americans with their imported color line dividing the Occupation from all Haitians?

How have these super-class citizens of this once-Republic been occupying themselves?

Living for years on under-paid peasant labor and lazy government jobs, is one answer.

Writing flowery poetry in the manner of the French academicians, is another. Creating bloody civil wars and wasteful political-party revolutions, and making lovely speeches on holidays. Borrowing government money abroad to spend on themselves — and doing nothing for the people without shoes, building no schools, no factories, creating no advancements for the masses, no new agricultural developments, no opportunities — too busy feeding their own pride and their own acquisitiveness. The result: a country poor, ignorant, and hungry at the bottom, corrupt and greedy at the top — a wide open way for the equally greedy Yankees of the North to step in, with a corruption more powerful than Paris-cultured mulattoes had the gall to muster.

Haiti today: a fruit tree for Wall Street, a mango for the Occupation, coffee for foreign cups, and poverty for its own black workers and peasants. The recently elected Chamber of Deputies (the Haitian Senate) has just voted to increase its salaries to $250.00 a month. The workers on the public roads receive 30c a day, and the members of the gendarmerie $2.50 a week. A great difference in income. But then — the deputies must wear shoes. They have dignity to maintain. They govern.

As to the Occupation, after fifteen years, about all for which one can give the Marines credit are a few decent hospitals and a rural health service. The roads of the country are still impassable, and schools continue to be lacking. The need for economic reform is greater than ever.

The people without shoes cannot read or write. Most of them have never seen a movie, have never seen a train. They live in thatched huts or rickety houses; rise with the sun; sleep with the dark. They wash their clothes in running streams with lathery weeds — too poor to buy soap. They move slowly, appear lazy because of generations of undernourishment and constant lack of incentive to ambition. On Saturdays they dance to the Congo drums; and on Sundays go to mass, — for they believe in the Saints and the Voodoo gods, all mixed. They grow old and die, and are buried the following day after an all-night wake where their friends drink, sing, and play games, like a party. The rulers of the land never miss them. More black infants are born to grow up and work. Foreign ships continue to come into Haitian harbors, dump goods, and sail away with the products of black labor — cocoa beans, coffee, sugar, dye-woods, fruits, and rice. The mulatto upper classes continue to send their children to Europe for an education. The American Occupation lives in the best houses. The officials of the National City Bank, New York, keep their heavy-jawed portraits in the offices of the Banque d’Haiti. And because black hands have touched the earth, gathered in the fruits, and loaded ships, somebody — across the class and color lines — many somebodies become richer and wiser, educate their children to read and write, to travel, to be ambitious, to be superior, to create armies, and to build banks. Somebody wears coats and shoes.

On Sunday evening in the Champs de Mars, before the Capital at Port au Prince, the palace band plays immortally out-worn music while genteel people stroll round and round the brilliance of the lighted bandstand. Lovely brown and yellow girls in cool dresses, and dark men in white suits, pass and repass.

I asked a friend of mine, my first night there. “Where are all the people without shoes? I don’t see any.”

“They can’t walk here,” he said, “The police would drive them away.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1931/v07n05-oct-1931-New-Masses.pdf