Fantastic article, the first of two, by Arne Swabeck, then organizer of the Communist Party’s Chicago District, on the history of struggle in the steel industry and the conditions of workers in modern mills.

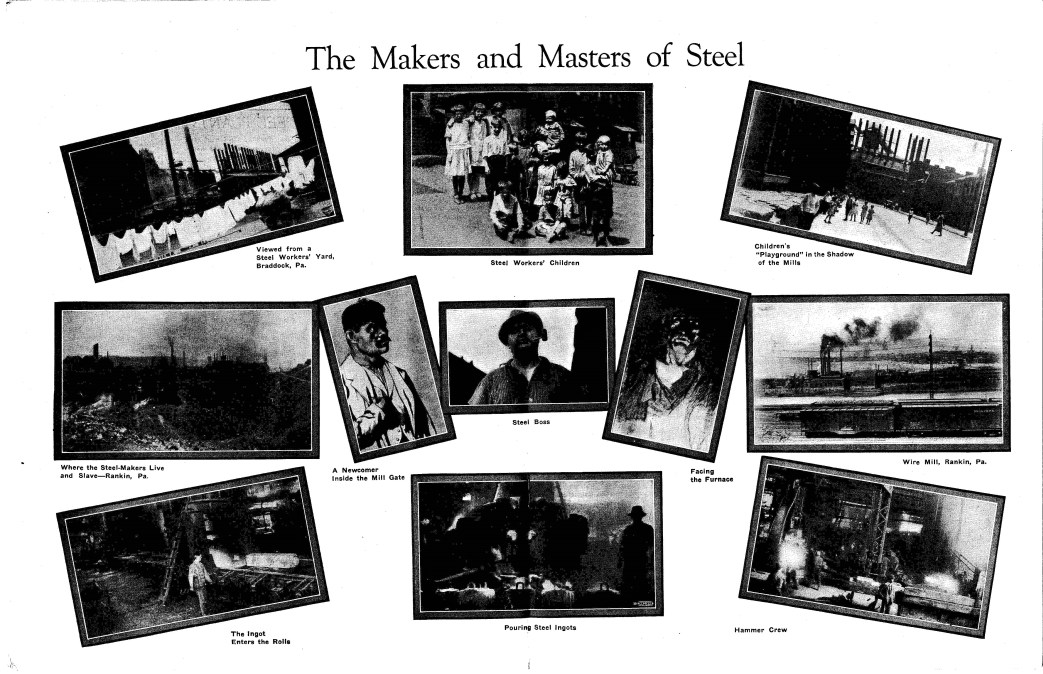

‘The Makers and Masters of Steel’ by Arne Swabeck from Workers Monthly. Vol. 4 No. 10. August, 1925.

In the hearth of the Pittsburgh steel district, officially designated by the home boosters, “the work shop of the world” thousands upon thousands of steel workers live lives of hazardous grueling toil, mercilessly exploited by the strongest capitalist combine ever created, exposed to persecution if they dare to utter rebellious thoughts, sometimes dropping from complete exhaustion and picking themselves up to struggle along through their hopeless existence, finding relief only in an early grave.

The steel workers are in the grip of an overwhelming power ready to crush everything and everybody who does not bend to its will. Yet the heroism and tenacity of the workers in actual combat with their relentless masters has more than once stirred the labor movement and given encouragement to the ever growing hope for working-class freedom.

In the Steel Towns.

Along the banks of the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio Rivers lie the gigantic blast furnaces and steel mills, most of them subsidiaries of the United States Steel Corporation. Down the Monongahela River for a stretch of forty miles on both banks gigantic plants crowd together hammering and throbbing day and night. Old-type tow boats tugging four to five barges plough the murky waters. Long freight trains are in constant motion on the river banks and heavy bridges with their endless load of raw materials and finished products.

A maze of steel and rails everywhere. Smoke stacks of the mills stand out like forests belching poisonous clouds of black and yellow which turn into flames whenever the hot, molten metal is poured and mixed with the various ingredients. This heavy smoke drifts over the filthy hovels which the steel workers call home, falling down as a thick and suffocating blanket. The river water spreads typhoid fever from the ruination due to sulphur acids coming from the mills.

Here are the steel towns whose names have become graven into labor’s history never to fade away, Homestead, Rankin, Braddock, McKeesport, Duquesne, Donora, Clairton, Monessen and others. All these towns are owned and controlled by the steel trust. Their dilapidated streets run right alongside the mills and furnaces. Big families squeeze into the wretched houses, the shift system at the mills allowing the introduction of the ingenious arrangement whereby three steel workers often sleep in the same bed, one after the other. Down at River Avenue in Braddock, when the water is high in the Monongahela the first floors become flooded. In front of every mill gate private policemen are stationed, armed with heavy batons, blackjacks and guns, taking their orders from their master—the Steel Trust.

Coming from Pittsburgh through East End, where stand the palatial dwellings of the plutes—the Mellons, the Babcocks, the Olivers and the Heinzes—and continuing on to the towns of Rankin, Braddock and Homestead one sees a contrast that powerfully illustrates the social abyss created by the class divisions of present-day society.

Fat Profits for the “lronmasters.”

Since the bessemer process became known in 1885 and made possible the production of rolled steel the industry has shown amazing growth, in development of implements, in productive capacity and in the piling up of profits. During 1899 the total steel ingot production amounted to 10,485,745 tons. In 1917 the output was 43,619,200 tons. This was however a war year and the steel business thrives on war; it was in fact a record year in the industry. The last six years have shown an average production of 34,750,000 tons. During the last few months a slackening has set in, production being about 70 per cent of capacity at the end of May.

During 1924, after deducting great sums for depreciation, depletion and bond interest, the net profits of twenty of the biggest steel concerns possessing approximately 85 per cent of the country’s ingot capacity amounted to a total of $134,400,000; the United States Steel Corporation alone realized $85,067,000.

The total investment in the United States Steel Corporation has today reached the stupendous sum of $1,562,234,000. And at the last stockholders’ meeting Judge Gary stated that the corporation has undivided surplus on hand of $517,061,308.

Something like 60,000 steel workers employed by the corporation are claimed to have become stockholders of the corporation, including mainly the clerical force, straw bosses and better paid mechanics. They, of course, cannot complain about working conditions. They must not do anything that may harm their “own” company. If in addition they live in a company house, buy in a company store, have a company loan and work toward a company pension they find themselves all “sewed up.” But if stock buying by the employes becomes too heavy the next wage cut is prepared. The corporation meanwhile uses their hard earned money for its tremendous expansions and to increase its power. It operates thousands of miles of railroads, ©wns vast coal fields, limitless metal mines, shipping lines, docks, shipbuilding yards, by-product plants and is closely tied to the country’s biggest banking institutions. Profits are piling up year after year for the owners of the United States Steel Corporation and the Steel Trust as a whole. Through direct investment and interlocking directorates they have become powerful factors in scores of other great industries. Their economic and political power is growing to fantastic heights.

Steel Trust Law.

The Steel Trust dominates the municipalities of all the little steel towns in the Pittsburgh district. The burgesses’ chair is invariably occupied by company officials or their near relatives. The chiefs of police are company tools. They cheat the municipalities of taxes. They use their political control to keep the workers unorganized. No working-class expression, no working-class meetings are permitted. Free speech does not exist. The unscrupulous burgesses are given unlimited sway to use their positions to close halls, break up gatherings of workers, place them under arrest if. they carry on strike activities, intimidate and terrorize workers and deport those of foreign birth. If any situation arises with which the mill police cannot cope the town or state police will be available, or even the military forces if necessary, as during the steel strike of 1919. The brutalities then perpetrated against the steel workers, the wholesale clubbing, shooting and jailing, equalled the worst white terrorist acts known to history.

All these town officials became notorious in 1919. No outrage was too revolting for them in their mad rush for Steel Trust favors. They have this reputation to the present day. Mayor Lysle of McKeesport, who won his spurs as a steel trust “crusader” in 1919, has made the boast that his record in fighting unionism and suppressing the workers has secured his re-election to office ever since. In 1923, about 1,000 men went out on strike in the McKeesport Tin Plate Company. Many of them were arrested for distribution of dodgers announcing a union meeting and in third degree sessions threatened with long-term imprisonment. Attempts to hold meetings were ruthlessly crushed. This unorganized strike was lost. A free speech fight led by members of the Workers Party at that time in the city of McKeesport brought imprisonment to a number of comrades. In the other steel towns a similar condition prevails.

Mighty Labor Struggles of the Past.

These are but a few incidents in a long series of bitter and bloody struggles. Defeat after defeat has been the lot of the steel workers during the last generation.

The first strike ever recorded was the one of Pittsburgh puddlers in 1849-50. But the beginning of the real struggles only dates back to 1858 with the organization of the Sons of Vulcan. Since then almost every new invention and new introduction of heavy machinery eliminated men from the mills and brought proposed wage cuts, most of them resulting in severe strikes.

The Homestead strike of 1892, extremely violent in character, attracted worldwide attention. Andrew Carnegie and H. C. Frick refused to deal with the union, hired scabs and imported 300 Pinkertons for their “protection.” From Ashtabula, Ohio, where they had gathered they were brought to a point on the Ohio River and at midnight on June 5th embarked on barges to be towed up the river to Monongahela and thence to Homestead where they arrived in the early morning hours of July 6th to be put ashore back of the mills. Here the striking workers had gathered, with their sympathizers, several thousand strong. A battle ensued, several were killed and the Pinkertons compelled to surrender and leave town. Finally, however, the strike was lost. This strike also marked a turning point in American industrial history. With it the trade union expansion, formerly a feature of the steel industry, came to an end and the day of untrammeled labor control by the employers arrived. The strike of 1901, subsequent upon the organization of the United States Steel Corporation and its determined, ruthless fight against unionism, brought defeat to the workers. However, the final death blow to the earlier trade union organization was administered in 1909 when the union was wiped out, not only in the United States Steel Corporation, but also in the larger independents. The strike at McKees Rocks Pressed Steel Car Company the same year was also extremely bitter in character, several workers being killed along with some state cossacks who attempted to protect the scabs.

Foster’s Moral and Practical Victory.

The great organization drive of 1919 and the subsequent strike was a wonderful demonstration of working-class solidarity and mass action. It will live as a great moral victory because it showed that what had been considered impossible was actually accomplished. Despite the half-heartedness and sometimes deliberate sabotage of many of the officials of the international unions entering into the drive, despite the great difficulties of the craft system of unionism and the stupid craft outlook on the part of these officials, for the first time in history a comprehensive and accurately estimated organization strategy was worked out and applied on a mass scale under the leadership of William Z. Foster. It consisted in a simultaneous drive from all directions against the main citadel—Pittsburgh. The strategy worked successfully; one fortress after another fell and the industry was conquered for organization. Then—criminal neglect and final betrayal by many of the union officials turned it into another defeat.

Facing the Furnaces.

There are a total of 399 blast furnaces in the country capable of making pig iron. Most of them are in the Pittsburgh district and the greater part of them are active at present. From these furnaces the iron is tapped as red hot molten metal. Men are constantly at work there, in shifts. When the blast furnace stoves need cleaning from the hardened cinder in combustion, which is performed by pick and shovel, a gang of from six to ten men gets on the job. To protect themselves against the extreme heat, the men put on wooden sandals, tie canvass to their legs and cover as much as possible of the face; but nothing can protect them from breathing in the hot flue dust. Ten minutes to one hour is the limit that a gang can stand the heat inside. If the stove tenders who manipulate the large, clumsy valves while the furnace is active perform the operations in the wrong order they are blown to bits. Sometimes men fall into the furnace and die instantly. Tending to blast furnaces in operation the men get no “spells” but keep on working until they sometimes drop from utter physical exhaustion. As stated by one steel worker from the Carnegie Homestead plant:

“If a man drops they take him to the office and give him some medicine; if he can he goes back to work, if he can’t he goes home. But you know if you go home you get no wages.”

There are three methods of converting cast iron into steel, viz., the crucible, the open hearth and the bessemer processes, producing different qualities of steel. The most extreme heat exposure is perhaps at the open hearth furnaces; heat being generated from about a dozen ovens containing from 30 to 75 tons of molten steel. At tap time when the hot liquid is poured into ingot molds, the men make “black walls,” which means throwing heavy dolomite across the blazing furnace. Four to five minutes work at which the temperature reaches 180 degrees. When the white hot steel is tapped into a ladle, sometimes 100 tons size, coal and manganese is shoveled into the ladle making flames leap high into the air, while the heat blasts everything to the roof. The motto laid down for the men is: “Get near enough to do the work without getting your whole face burned off.” The most exposed parts of the body are almost sure to get minor burns and it is almost always necessary to extinguish little fires from the clothing. Hot metal explosions are common occurrences and generally fatal to the workers,

At the bessemer converter the steel pourer and his helpers work day by day beside a ladle brimming with from 10 to 15 tons of seething liquid steel.

Where Life is Cheap.

The molten steel is poured into ingot molds 18 to 24 inches in diameter and as soon as the ingots are cold enough to stand alone they are stripped of the molds and while still red hot hauled by dinky engines to the rolling mills where they are flattened into shapes suitable for the market. It sounds like a thunderbolt when an ingot hits the rolls and when the cold saws bite into steel plates a deafening screech is produced. The noise becomes a terrible strain on the workers.

At the finishing mills roughers and catchers leap at their work, thrusting red hot billets through the rolls. Real agility is required, a stiff joint or a misstep may mean instant death. At the rod and wire mills the red hot wires dart with lightning speed like snakes through the rolls several at a time and if catchers are too slow with their tongs a limb may be cut off.

Many accidents occur at the heavy machines and huge cranes. It is difficult for men worked to the point of complete physical exhaustion to be sufficiently on the alert to avoid fatalities and the iron and steel mills have taken a heavy toll of human lives. Workers’ lives were cheap, particularly those brought in from foreign shores, with no relatives in the country and no one to ask what became of them. According to the “Pittsburgh Survey” an investigation made in 1907 showed that for the loss of an eye in several instances as low compensation as $48 was paid, the loss of a leg was compensated by as little as $55 and in some cases there has been no compensation whatever. Out of 42 deaths caused by accidents at the Carnegie mills compensation was paid to 10 families, the amount in each case being $1,000 or less.

Some safety devices are applied in the Pittsburgh mills but it is found much cheaper to fill the workers up to stuffing with safety lectures. Never a day passes in any of these mills without some accident. One steel worker at Braddock who had lived for years on Clara Street, told of his family witnessing day by day the injured being carried on stretchers to the company hospital. “Just three weeks ago,” said he, “A red hot rail went clean through a man and he was taken out quietly and buried. I was working only a few feet away from him but it was hushed up and I learned nothing of it until a few days after.” The company does not care to have accidents known.

The Blacklist.

The blacklist system, although of the crudest kind, works with brutal efficiency in the steel mills. When a man applies for a job the agent first takes his complete description on especially prepared blanks, as well as his fingerprints. The office blacklist is consulted and if the man’s name, description or fingerprint is on the list there is no opening for him.

During the great organization drive and subsequent strike of 1819 any worker caught active on behalf of unionism was immediately entered on the blacklist, which was furnished to all the mills of the district. Spies and provocateurs, either directly in the employ of the trust or supplied by private detective agencies, swarmed amongst the workers to provoke them into making definite statements starting disturbances. They would report their unsuspecting fellow workers to the companies as “dangerous radicals”, from whence the report would go to the town and state police and federal government to be used to crush any move by the workers and victimize those reported. Whose government it is became quite clear.

Today the spies are as thick as ever amongst the workers and precisely the same methods are being used.

The Lean Pay Envelopes of the Unorganized.

Many steel workers curse the day they first stepped inside the mill gate, but it is not so easy to get out again;— the kiddies must be fed no matter how long the working hours, no matter how miserable the conditions nor how great the suppression. The gigantic Steel Trust runs its plants on a highly militarized basis. The ever growing army of common laborers are treated worse than slaves. Economic division among the workers is deliberately stimulated, while a prostitute sense of loyalty to the company is developed among the straw bosses and some of the more highly skilled mechanics. The latter stupidly believe their economic interests are threatened by the unskilled, blissfully ignorant that their skill is being undermined by the development of machinery.

Working hours in the mills are still anywhere from 8 to 14, and wage rates have a yet wider range. Rollers sometimes receive as much as $30 a day, doublers $10 to $14, heaters $9, catchers and roughers $7 to $8. These are however the highly skilled crafts making up a small minority of the mill force.

The large army of unskilled workers at present receives from 40 to 50 cents an hour. No worker has any say in fixing the rates but must take whatever he receives in the pay envelope or get out. These are the conditions of the unorganized. Unionism is taboo in the steel mills.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v4n10-aug-1925.pdf