‘William H. Sylvis: Unrecognized Genius’ by James Sand from Workers Age (Communist Party (Opposition)). Vol. 4 No. 49. December 14, 1935.

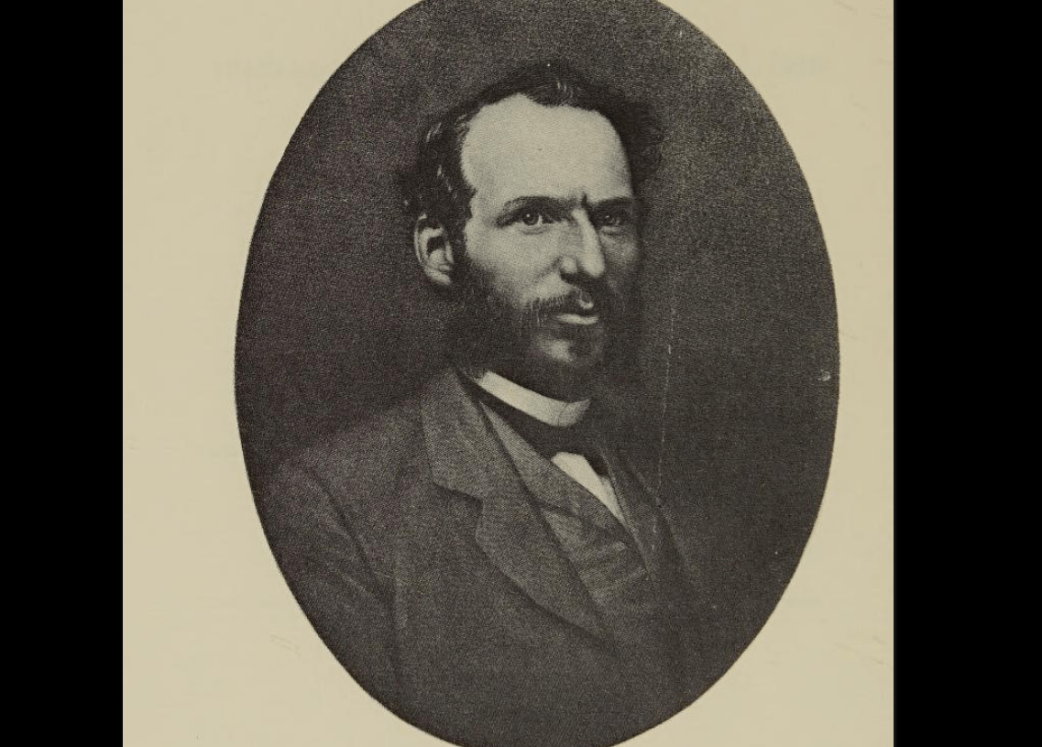

THE history of American labor leadership opens with a man of great vision, unbounded power that, despite its achievement, never reached the full flower of its potentiality because of his death before fifty. From some few specialists in the field of American labor the name of William H. Sylvis gains immediate response and praise; but to the great mass of workers he is not even a name. But one book has been devoted to him, and that written by his brother in 1872 and very difficult to obtain. Yet he is the first great proletarian; a Marxist before one can really speak of Marxism, a great labor leader before there even was a great labor movement to lead.

A TIRELESS ORGANIZER

A study of his life falls into three large categories: his work in his own occupational union, his work in the National Labor Union, and his work for, by, and with the International Working Men’s Association, the First International. He was born on November 26th, 1828 in Armagh, Pennsylvania, the second son of a journeyman wagon maker. At eleven he still had had no schooling and then he received lessons in the alphabet only after he had been hired out to a man named Pawling. At eighteen he learned his trade, iron molding, and followed that until he threw himself with fervor and devotion into the budding labor movement.

On January 10th, 1860 in a convention of 12 local molders’ unions he had a motion adopted “that this convention does now resolve itself into a national union.” The panic of 1857 had wiped out the small buds of a trade union movement and this young national union was to be a nucleus for the later National Labor Union. But the Civil War intervened and for a time put an end to the organization. Sylvis himself served in the Northern army for about a year, but soon returned home disgruntled.

In 1863 the union revived again and at a convention in Pittsburgh he was elected president and national organizer. He was reelected to the presidency every year until his death. “From the day of that vote,” says Stockton, the historian of the union, “the Molders entered upon a new era.” On beginning his work as national organizer Sylvis said he had “no very clear conception of the extent of the task before me, or the means by which it was to be accomplished.” His brother has given a graphic description of his days as organizer. “During this: period,” he says, “Sylvis wore clothes until they became quite threadbare, and he could wear them no longer; the shawl he wore to the day of his death was filled with little holes, burned there by the splashing of the molten iron from the Iadles of molders in strange cities, whom he was beseeching to organize, and more than once he was compelled to beg a ride from place to place on an engine, because he had no money sufficient to pay his fare.”

Through his efforts that year of 1863-64 all the existing locals grew stronger, 16 were reorganized, and 18 new ones were added. The Iron Molders thus had 50 local unions, practically as many as all other crafts combined. Already in 1859 in an address-to the convention that founded the national union he had propounded a social doctrine far in advance of the times.

”In all countries and at all times (he wrote) capital has been used by those possessing it to monopolize particular branches of business, until the vast and various industrial pursuits of the world have been brought under the immediate control of a comparatively small portion of mankind. What position are we, the mechanics of America, to hold in society? Are we to receive an equivalent for our labor sufficient to maintain us in comparative independence and respectability, to procure the means with which to educate our children, and qualify them to play their part in the world’s drama; or must we be forced to bow the suppliant knee to wealth, and earn by unprofitable toil a life too void of solace to confirm the very claims that bind us to our doom,?”

From this general humanitarian position with its deep insight into the class struggle he was to move ahead, thru an understanding of the Civil War and onrushing capitalism, to forge a doctrine as close to Marx as he could get in the few years that remained of his life.

Sylvis’ work had the employers in the industry scared, and they founded an employers’ association in 1863 to oppose the Molders’ Union. Their prospectus has the ring of excessive modernity:

“Instead of calling upon the employers to cooperate with their union in advancing the ‘moral, social, and intellectual condition of every moulder,’ which self-evidently is a matter of common interest, the ‘Moulders’ Union” even goes so far as to expel a member as soon as he has succeeded in establishing himself independently in business. We deny the right of the ‘Iron Moulder’s Union,” or any other Union, to arbitrarily determine the wages of our employees, regardless of their merits and the value of their services to us. We deny the right of the ‘Iron Moulders’ Union’ to determine how many apprentices we should employ. We shall resist by all legal means, at every sacrifice of time and money, all attempts of any set of men arbitrarily to regulate the supply of labor in any department of trade and business.”

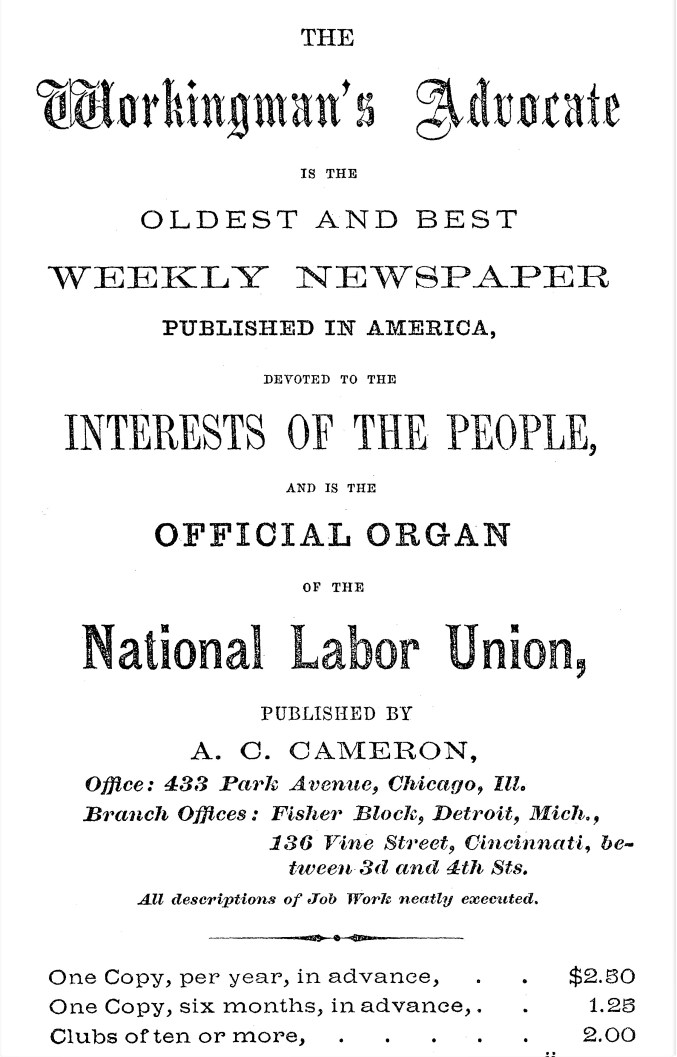

NATIONAL LABOR UNION IS BORN

The National Labor Union was formed in 1866 and there Sylvis was admitted as the accredited representative of the molders. Within two years he is its president and an international figure in the labor movement. At the 1861 convention in Chicago Sylvis becomes an important delegate. There, he came into conflict with a certain Mr. Gibson who opposed the organization of white workers and Negroes into the same trade unions. Mr. Gibson said it would be time enough to consider the question when Negroes applied for admission. Sylvis said in answer that the question had been already introduced into the South, the whites “striking against the blacks, and creating an antagonism which will kill off the trades’ unions, unless the two be consolidated.” In the same convention Sylvis was a member of the Committee on Public Lands and he submitted a resolution which was adopted. It said in part:

“The course of our legislation recently, has tended to the building up of greater monopolies, and the creation of more powerful, moneyed and land aristocracies in the United States than any that now overshadows the destinies of Europe. Eight hundred millions of acres of the peoples’ lands have been legislated into the hands of a few individuals, who already assume a haughty and insolent tone and bearing towards the people and government, as did the patricians of ancient Rome.”

At the convention of 1868 in New York City which opened on September 21, 1868, Sylvis was in the thick of the fight. In debate on the financial question he came to a homely statement of the class struggle. He said: “Under our present monetary system, all the people who are borrowers must borrow money from banks or brokers—money shavers. The people of the United States are divided into two classes-the skinners and the skinned—the borrowers being the skinned, and the bankers the skinners. A bank in any shape is a licensed swindle; and the greatest swindle ever imposed upon our people is our present national banking System. Another gentleman says we have got too much money. I have not got too much. Has any gentleman on the floor? We have not got nearly enough money, and what little we have is gobbled up by a few rich men in New York and elsewhere.” He also proposed that the convention pass a resolution demanding the creation of a Department of Labor and Census Statistics, “said department to have charge, under the laws of Congress, of the distribution of the public domain, the registration and regulation, under a general system, of trade unions, cooperative associations, and all other organizations of workingmen and women having for their object the protection of productive industry, and the elevation of those who toil.” It was not until 1913 that a separate Department of Labor was instituted in the president’s Cabinet, and it is surely not the kind that Sylvis wanted.

At this convention Sylvis was elected president of the National Labor Union. He died before his year of office was up, but not before he had put himself on record in favor of a labor party. In his. first years as president of the Molders’ Union he had been active in the Philadelphia Trades’ Assembly. At this time he was opposed to independent political action by labor. He propounded the doctrine of rewarding friends and punishing enemies which Gompers later took over as the foundation of the A. F. of L.’s political position. But after his election as president of the National Labor Union he came out for the formation of a labor party in a circular issued to the trade unions. He said:

“The organization of a new party, working man’s party- for the purpose of getting control of Congress and the several State Legislatures, is a huge work; but it can and must be done. We have been tools of professional politicians of all parties long enough; let us now cut loose from all party ties, and organize a working-man’s party, founded upon. honesty, economy and equal rights and equal privileges to all men. Money has ruled us long enough; let us see if we cannot rule money for a time.”

In a second circular he evinces a. grasp of the significance of the Civil War for the working class which ranks with the incisive understanding of Marx and Engels at this time. He said:

“The working people of our nation, white and black, male and female, are sinking to a condition of serfdom. Even now a slavery exists in our land worse than ever existed under the old slave system. The center of the slave power no longer exists south of Mason and Dixon’s line. It has been transferred to Wall Street; its vitality is to be found in our huge national bank swindle, and a false monetary system. (This last is a manifestation of Sylvis’ ‘Greenback’ tendencies.) The war abolished the right of property in man, but it did not abolish slavery. This movement we are now engaged in is this great anti-slavery movement, and we must push on the work of emancipation until slavery is abolished in every corner of our country.”

In the spring of 1869 Sylvis died, and the incomplete president’s address he prepared was read at the national convention. It showed that he had opened extensive correspondence, distributed circulars, and appointed a committee of five to reside in Washington during the session of Congress. This last is the first labor lobby inaugurated in America.

RELATIONS WITH FIRST INTERNATIONAL

It remains to speak of Sylvis’ relations with the First International which had been founded in London in 1864, had soon come under the broadening influence of Marx. Sylvis wanted not only a delegate of the National Labor Union at the annual sessions of the International, but also an agent to be sent to Europe to investigate labor conditions there and inform the European workers of conditions in America. In 1868 the National Labor Union was unable to accept the International’s invitation to send a delegate because no money was available for his expenses. The first American delegate was sent in 1869 after Sylvis’ death, but he had already been in correspondence with the General Council of the International that spring. He had answered the Council’s request to lead American labor’s fight against a war between England and the United States which appeared imminent in May 1869 with the following letter:

“I am very happy to receive such kindly words from our fellow workingmen across the water; our cause is a common one. It is a war between. poverty and wealth; labour occ1ipies the same low condition, and capital is the same tyrant in all parts of the world. Therefore I say our cause is a common one. I, in behalf of the working people of the United States, extend to you, and thru you those you represent, and to all the down-trodden and oppressed sons and daughters of toil in Europe, the right hand of fellowship. Go ahead in the good work you have undertaken, until the most glorious success crowns your efforts. That is our determination. Our late war resulted in the building up of the most infamous monied aristocracy on the face of the earth. This monied power is fast eating up the substance of the people. We have made war upon it, and we mean to win. If we can, we will win thru the ballot-box; if not, then we will resort to sterner means. A little blood-letting is sometimes necessary in desperate cases.”

Whether the American workers would have been saved the disruptive experience of the Knights of Labor if Sylvis had lived no one can say. But it is undoubted that he would have imbued at least some great part of the growing American proletariat with a class viewpoint, the need for independent political action, the solidarity of Negro and white workers, the need for militant trade unionism and the effective use of the striking power. That the development of American capitalism, the bourgeoisification of the American worker, the “land-of-opportunity” psychology of the large army of immigrants, the undeveloped class-consciousness of the working masses, would have stopped him at many turns we cannot doubt. But that labor would have been advanced decades by his activity Marx himself recognized thru the General Council of the First International which recorded its condolences on Sylvis’ death with the following communication:

“That the American labor movement does not depend on the life of a single individual is certain, but not less certain is the fact that the loss sustained by the present labor convention cannot be compensated. The eyes of all were turned on Sylvis, who, as a general of the proletarian army, had an experience of ten years outside of his great abilities and Sylvis is dead.”

Workers Age was the continuation of Revolutionary Age, begun in 1929 and published in New York City by the Communist Party U.S.A. Majority Group, lead by Jay Lovestone and Ben Gitlow and aligned with Bukharin in the Soviet Union and the International Communist (Right) Opposition in the Communist International. Workers Age was a weekly published between 1932 and 1941. Writers and or editors for Workers Age included Lovestone, Gitlow, Will Herberg, Lyman Fraser, Geogre F. Miles, Bertram D. Wolfe, Charles S. Zimmerman, Lewis Corey (Louis Fraina), Albert Bell, William Kruse, Jack Rubenstein, Harry Winitsky, Jack MacDonald, Bert Miller, and Ben Davidson. During the run of Workers Age, the ‘Lovestonites’ name changed from Communist Party (Majority Group) (November 1929-September 1932) to the Communist Party of the USA (Opposition) (September 1932-May 1937) to the Independent Communist Labor League (May 1937-July 1938) to the Independent Labor League of America (July 1938-January 1941), and often referred to simply as ‘CPO’ (Communist Party Opposition). While those interested in the history of Lovestone and the ‘Right Opposition’ will find the paper essential, students of the labor movement of the 1930s will find a wealth of information in its pages as well. Though small in size, the CPO plaid a leading role in a number of important unions, particularly in industry dominated by Jewish and Yiddish-speaking labor, particularly with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Local 22, the International Fur & Leather Workers Union, the Doll and Toy Workers Union, and the United Shoe and Leather Workers Union, as well as having influence in the New York Teachers, United Autoworkers, and others.

For a PDF of the full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-age/1935/v4n49-dec-14-1935-WA.pdf