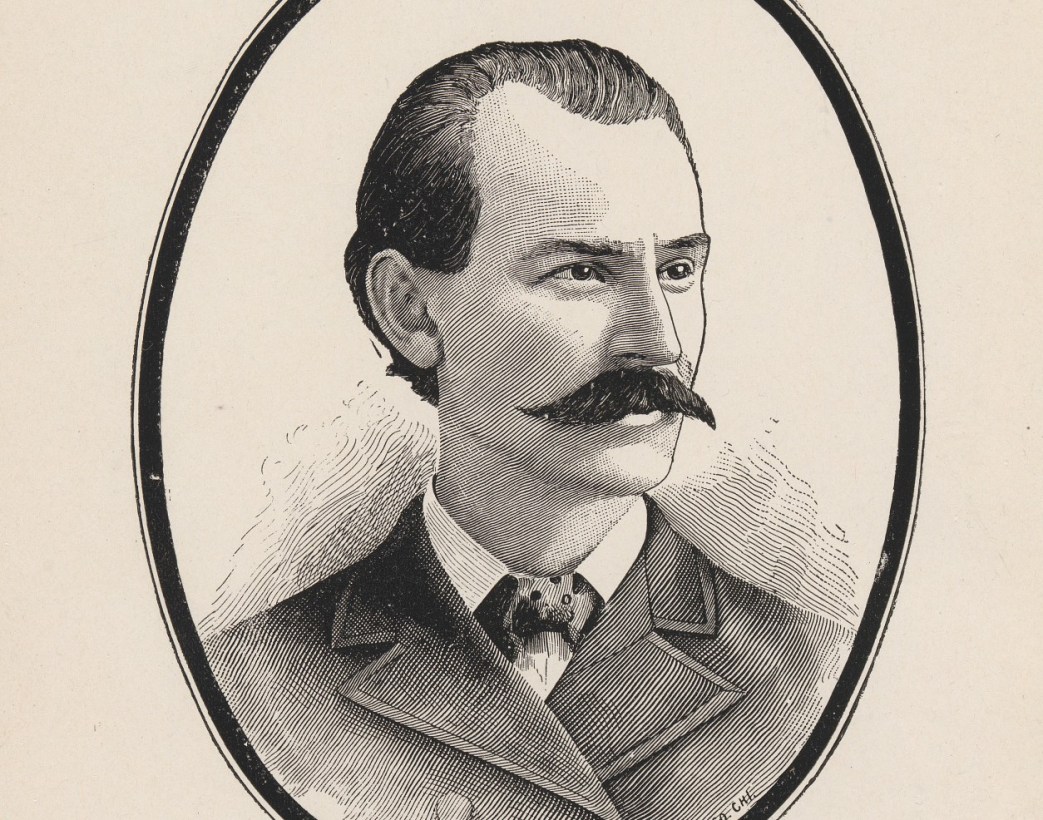

‘What Anarchy Means’ by Albert R. Parsons from The Alarm. Vol. 1 No. 18. March 7, 1885.

The manifesto of the Pittsburg Congress of the International Working People’s Association, issued October 16, 1883, concludes as follows:

What we would achieve is therefore plainly and simply:

First—Destruction of the existing class rule by all means; i.e., by energetic, relentless, revolutionary and international action.

Second—Establishment of a free society based upon co-operative organization of production.

Third—Free exchange of equivalent products by and between the productive organizations without commerce and profit-mongery.

Fourth—Organization of education on a secular, scientific and equal basis for both sexes.

Fifth—Equal rights for all without distinction to sex or race.

Sixth—Regulation of all public affairs by free contracts between the autonomous (independent) communes and associations, resting on a federalists basis.

Whoever agrees with this ideal let him grasp our outstretched brothers’ hands!

Proletarians of all countries, unite!

Fellow-workmen, all we need for the achievement of this great end is organization and unity.

The above declaration sets forth the aims and methods of the Anarchists. It is, therefore, a matter of surprise to hear some per¬ sons say that Anarchists are without design or purpose.

We often hear it asked, ‘What does Anarchy mean?” It means first, the destruction of the existing class domination. Until this is accomplished reform or improvement in any direction in the interest of the proletariat is an impossibility. All the ills that inflict mankind are summed up in one word— poverty —resulting from unnatural causes. Remove this barrier from the pathway and the march of progress will be steady and rapid toward the highest forms of civilization. Poverty, therefore, is the great curse of man.

The domination of classes arises from privileges acquired first, by force and chicane, and then enacted into statute law, and made legal by a constitution. Through this process the means of existence, without the use of which life cannot be maintained: land, machinery, transportation, communication, etc., have been made private property —monopolized—until only a few privileged persons in society possess the right to live in liberty. The propertyless, the wage class, are compelled to seek for bread and shelter of those who possess property. Out of this compulsion arises the slavery and poverty of the wealth-producers. The private property system is a despotism under which the propertyless are forced, under penalty of starvation, to accept whatever terms or conditions the propertied may dictate. To remove this system is the first and paramount aim of Anarchy, and for its accomplishment a resort to any and all means becomes not only a duty but a necessity. The ballot-box has ceased long since to record the popular will, for he who must sell his vote or starve, will sell his vote also, when the same alternative is presented. The class who control the industries and the wealth of the country can and do control its votes. Education be¬ comes impossible under the drudgery and poverty of wage-slavery, and of itself can make no change. The International recognizes that the man of labor is held by force in economic subjection to the monopolizers of the means of labor, the resources of life, and that from this source arises the mental degradation, the political dependence and social misery of the working class.

The proletariat being no longer able to live except in slavery, and a large portion of them denied even that choice, the revolutionary movement becomes an absolute necessity. This revolutionary movement, consisting of the discontented and starving proletariat, is organized into an irresistible power by those men of the wage class who have a historical insight into the labor movement and the outcome of the social revolution.

There are educated men of the middle class, who, seeing the approaching conflict, or having been themselves crushed out by the weight of competition and forced into the ranks of the proletariat, become active and useful members in organizing the elements of discontent.

The State and its laws serve only to perpetuate the existing class rule, and once overthrown, upon its ruins Anarchy would place a “free society, based upon the co-operative organization of production.” This free society would be purely economic in its character, dealing only with the production and distribution of wealth. The various occupations and individuals would voluntarily associate to conduct the process of distribution and production. The shoe¬ makers, carpenters, farmers, printers, moulders, and others would form autonomous or independent groups or communities, regulating all affairs to suit their pleasure. The trades unions, assemblies and other labor organizations are but the initial groups of the free society.

Freedom of exchange between the productive organizations with¬ out commerce or profit-mongery would then take the place of the existing speculative system with its artificial scarcity and plundering “corners.”

Education would be placed within the reach of all.

Equal rights would exist for all. No rights without duties; no duties without rights.

All public affairs would be regulated by free contracts between the autonomous (independent) communes or groups, resting on a federalistic basis.

The free society is the abrogation of all forms of political government. The useless classes, lawyers, judges, armies, police, and the innumerable hordes engaged in buying, selling and advertising their wares, would disappear. Reason and common sense, based upon natural law, takes the place of statute law, with its compulsion and arbitrary rules.

Capital, being a thing, can have no rights. Persons alone have rights. The existing system bestows all capital upon one class and labor upon the other; hence the conflict is irrepressible. The time has now arrived when the laborers must possess the right to the free use of capital with which they work, or the capitalists will own the laborers, body and soul. No compromise is possible. We must choose between freedom and slavery. The International defiantly unfurls the banner of liberty, fraternity, equality, and beneath its scarlet folds beckons the disinherited of earth to assemble and strike down the property beast which feasts upon the life-blood of the people.

The Alarm was an extremely important paper at a momentous moment in the history of the US and international workers’ movement. The Alarm was the paper of the International Working People’s Association produced weekly in Chicago and edited by Albert Parsons. The IWPA was formed by anarchists and social revolutionists who left the Socialist Labor Party in 1883 led by Johann Most who had recently arrived in the States. The SLP was then dominated by German-speaking Lassalleans focused on electoral work, and a smaller group of Marxists largely focused on craft unions. In the immigrant slums of proletarian Chicago, neither were as appealing as the city’s Lehr-und-Wehr Vereine (Education and Defense Societies) which armed and trained themselves for the class war. With 5000 members by the mid-1880s, the IWPA quickly far outgrew the SLP, and signified the larger dominance of anarchism on radical thought in that decade. The Alarm first appeared on October 4, 1884, one of eight IWPA papers that formed, but the only one in English. Parsons was formerly the assistant-editor of the SLP’s ‘People’ newspaper and a pioneer member of the American Typographical Union. By early 1886 Alarm claimed a run of 3000, while the other Chicago IWPA papers, the daily German Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper) edited by August Spies and weeklies Der Vorbote (The Harbinger) had between 7-8000 each, while the weekly Der Fackel (The Torch) ran 12000 copies an issue. A Czech-language weekly Budoucnost (The Future) was also produced. Parsons, assisted by Lizzie Holmes and his wife Lucy Parsons, issued a militant working-class paper. The Alarm was incendiary in its language, literally. Along with openly advocating the use of force, The Alarm published bomb-making instructions. Suppressed immediately after May 4, 1886, the last issue edited by Parson was April 24. On November 5, 1887, one week before Parson’s execution, The Alarm was relaunched by Dyer Lum but only lasted half a year. Restarted again in 1888, The Alarm finally ended in February 1889. The Alarm is a crucial resource to understanding the rise of anarchism in the US and the world of Haymarket and one of the most radical eras in US working class history.

PDF of full issue: https://dds.crl.edu/item/54011