Austin Lewis was the leading Marxist theorizing industrial unionism in the United States before World War One. Among his most important works, meant to become a book, were a series of articles on on the politics, economy, and psychology of ‘solidarity’ for the New Review. Here is his contribution on the scab.

‘Solidarity and Scabbing’ by Austin Lewis from New Review. Vol. 3 No. 6. May 15, 1915.

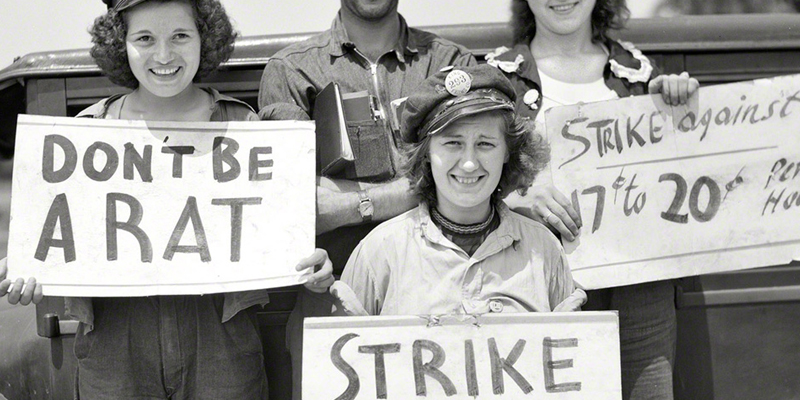

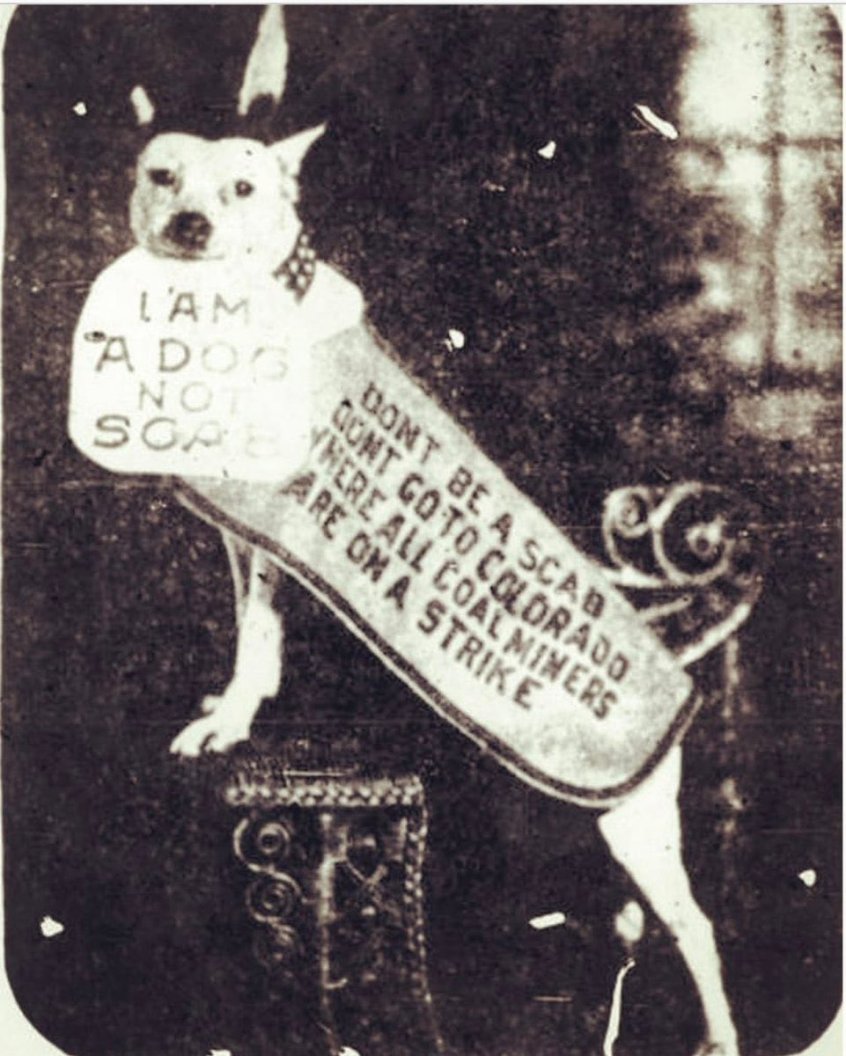

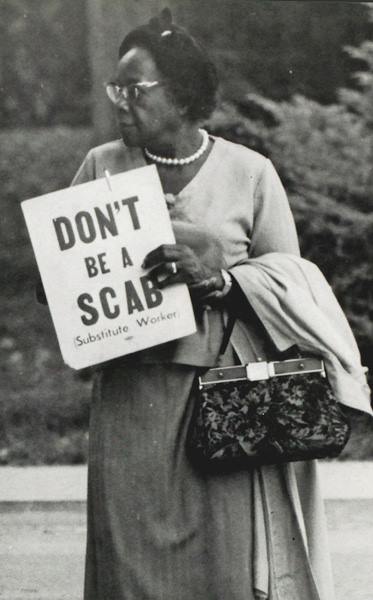

WE are all familiar with the punishment of the scab and the approval which such punishment meets among working people. This approval, even of actual violence, is an abhorrent surprise to the middle classes. That one cannot work when he likes where he likes and for what he likes, strikes at the very foundations of that individual liberty which underlies the middle class state and which the ordinary middle class citizen regards as essential to his welfare. But such liberty has been found to be incompatible with the prosperity and even with the life of working people, and hence, the workers obedient to the ordinary ethical code as they are, are obliged by the circumstances of their life to make another ethical code. which transcends the value of the former since it is obligatory upon them, or to use the current term, “makes for life.”

With the advent of the solidarity notion however the question of scabbing becomes even more important than before, for it is vital to organized labor that it should be able to maintain itself intact and present a firm front to its enemies.

It could only do this in the future as it has frequently done in the past by virtue of a sort of terrorism combined with sentimental appeals if it were not for the growth in the idea of labor solidarity. But the development of industry, with the gradual substitution of unskilled for skilled labor, has worked a recent and rapid change in the conditions with which skilled labor is confronted in times of strikes or lock outs.

Under the system in which the skilled had a sort of monopoly by virtue of his skill, the justification of the use even of violence against scabs is very apparent. The strikers, or the men locked out, were engaged in a fight which tended to improve or maintain conditions in the particular craft. All who practised that craft share, of necessity, in the gains made for it by organized labor, even though they were not members of the union. The treachery of those who, for a transitory and monetary advantage took the place of their fellow craftsmen and thus reduced the standing of the entire labor body is very apparent. None but the very meanest and most contemptible of men would act as scabs under such conditions, and there is no question of the moral inferiority of the scabs of that period.

But it may happen and indeed increasingly happens that the skilled craft is artificially and unsocially maintaining conditions which are uneconomic and have no industrial justification. This is shown by the fact that unskilled can be substituted for skilled in the event of a strike or lock out. This has been done repeatedly in recent times. In fact unskilled Italians have been known to break a strike in the metal trades and to become so-called skilled workers in the course of a few months.

It is hard for the skilled trades to find any real ground of complaint against these scabs. They do not belong to their organization, they do not even belong to their craft. Benefits which might arise to the craft from the strike do not appeal to them for they will never be members of the craft. They are working in iron today, they may be working in wood tomorrow. There is no appeal to be made to them on any common ground from the trade union point of view.

Indeed they are in such a position that they have a grievance against the skilled crafts which have not only not done anything for them but have actually put obstacles in their way and have made the tiresome work of earning a living even more difficult than necessary.

So bitterly is this grievance felt in fact that at times the so-called unskilled so far as organized they have frequently resolved to carry on a campaign against the skilled trades from whom they have had so little sympathy and so much antagonism. But they have always refrained from putting their threats into deeds because of that tendency towards solidarity which is so much more effective in the weak than in the strong. Moreover, the feeling, at least among the leaders, that war between the various sections of labor could have nothing but a detrimental effect upon the movement as a whole, has been so powerful that the malcontents have had no chance to put their threats into effect.

Only the most earnest feeling of solidarity could compel men in such a condition as are the unskilled to refrain from scabbing. For the work to which they could gain access by scabbing on the skilled offers so many opportunities for better pay that very marked self denial is required for its refusal.

The extent of the growth of the solidarity notion may be gauged by comparing the conduct of the unskilled in this respect with that of the organized skilled crafts who frequently scab upon one another. In most of such cases jurisdictional disputes are fundamental causes and, as a result of the ill-will and actual hatred engendered by these disputes, we find members of the same craft destroying each other and using actual physical violence in the prosecution of their hatreds.

The strike of electrical workers on the Pacific Coast in 1913 was one of the most notable among many of such occurrences. In this case one organization of electrical workers sided with the employers and when the other union went on strike promptly supplied scabs and worked with the result that hundreds of men were ruined and the efforts made towards improvement in conditions were thrown away.

This case in fact is merely typical of a large number of such which have all tended to make the craft union form more and more popular.

Yet such actions are quite justifiable on an hypothesis which does not set up a standard of solidarity. In fact the case of the electrical workers was regarded in trade union upper circles as disciplinary and as tending to assert the authority of the Federation officers who had declared against one union on the ground of lack of submission to authority.

Still the action of the union which scabbed upon the striking union was popularly regarded as utterly reprehensible and the great majority of the unionists on the Pacific Coast had sympathy for the striking union. Nothing but its defeat really reconciled the mass of the workingmen to the situation which was, of course, hopeless after that. An occurrence like this tends to show that the solidarity notion is making headway even among the trade unionists and that another standard than mere craft welfare is being set up.

In this connection we may note the criticism of Jim Larkin in his article “The Underman” in the March, 1915, number of the International Socialist Review.

Larkin is a labor leader of tremendous vigor and ability who has managed to get results from material hitherto considered as impossible by the average labor manager. His success has lain in the efficient organization of unskilled labor. Concerning American Federation manifestations in this country he says:

“The Railway Workers are organized in thirteen different unions, each of them charged with having scabbed on the other, and one is humiliated as a worker by being compelled to listen to a gentleman named Brandies boasting that a union spent a million dollars in assisting a shoe manufacturer to break a strike.”

In all these instances we find the old ethic, which is not the solidarity but the craft ethic, influencing the actions of the members of the skilled unions. The contrast between this and the new solidarity ethic as exemplified in the actions of the skilled unions as far as they have been organized is sufficiently obvious.

But whereas the trades unions do not scruple to scab upon one another they have naturally still less hesitation in scabbing upon the unskilled.

When a strike has continued for a few weeks and the pinch begins to be felt, numbers of the skilled men on strike are obliged to turn to unskilled labor in order to live. They invade the construction camps and farms and orchards and as they do not look forward to any prolonged period of employment at such occupations they are not particularly interested in maintaining any standards. They work under conditions and for rates of pay which the unskilled who are obliged to make their livelihood permanently at such occupations are struggling to improve, and they thus reduce the general standard for the unskilled and render their attempts at betterment all the more difficult.

This has occurred many times in the West in the history of the attempts of unskilled labor to improve itself. Even where strikes of the unskilled have been made we find the same willingness on the part of the organized craftsmen to actively operate against the strikers. This was true in the very important Big Creek strike in California which was conducted under the auspices of the Industrial Workers and was really vital to the interests of men engaged in the basic Western occupation of construction work.

The case of McKees Rocks, in which an actually victorious strike of unskilled workers was ruined by the scabbing of skilled men is one of the most disgraceful episodes in the history of recent trades unionism.

But in all these cases the actions of the trades unionists did not spring from any wanton desire to injure. They were caused by the fact that the men so scabbing did not understand that they were scabbing. Their ethic reached only to the effects of their actions upon organized trades and not upon workers as workers.

In this respect their point of view is not unlike that of the ancient Greeks whose civism extended only to those who had a panoply and who consequently had no moral responsibilities towards their inferiors who were not so fortunately situated.

Regarding the philosophical concepts behind these manifestations, we are all aware that they are but the persistent natural rights notions which as Robert Rives La Monte (NEW REVIEW-March) has again reminded us are the product of petty handicraft. His remarks in that connection are worth repeating. He says:

“Petty handicraft was moribund in England in the seventeenth century, it was all but dead and buried at the dawn of the nineteenth, and here we are in the second decade of the twentieth still defending or attacking capitalism with weapons forged on the intellectual anvil of petty handicraft.”

These words are still more applicable to the actions of organized labor as far as it has so far manifested itself not only in this country but elsewhere.

The ethical teachings of the machine process have not as yet begun to make themselves felt, unless somewhat feebly among the unskilled workers who are its more immediate victims. These consequently respond more readily to the solidarity idea for in that notion is their sole hope of relief.

If it were possible for a class to change the view point which the circumstances of its origin forced upon it, that class could save itself. But history has shown that such a transformation is impossible. Hence it is extremely improbable, to say the least, that the trades unions can transform themselves into an organization having an ethical basis resting on solidarity rather than on natural rights.

Still, the machine industry is at work and the ethical effects of that industry must of necessity make their impress upon the brains and conduct of the members of the trades who are brought into contact with it. The process is going on as we can see by the sympathy which has risen spontaneously in the ranks of organized labor for the unskilled, as in the Wheatland case. But it has so far not proceeded far enough to affect conduct and it cannot do so without transcending the limits of craft unionism and importing an ethical concept which trades unionism is not capable of supporting.

The higher industrial form should, as a matter of necessity, imply the higher industrial ethical and really does so. La Monte says that he sees no sign of the action of the machine industry upon the ethical consciousness of the workers, and he claims that Veblen is unable to discover such signs, except in the phenomenon of syndicalism. But conscious Syndicalism is in reality the least of these signs. The new life appears everywhere inside the organization even in its present form. Where they appear however they also threaten the organization, as it now exists. Proof of this is to be found in manifestations which can only be apparent to the close observer of actual phenomena in the world of labor itself. To see them one must be in close contact with the workers themselves. They are necessarily hidden from the student and the critic. If given an opportunity I should be glad to deal with some of these manifestations in later articles.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n06-may-15-1915.pdf