In the interwar years, there was no heavy industry where Black workers played a role as key as in steel. Any successful organizing in the industry required an appeal to Black workers and inter-racial solidarity. Most failed. C.L.R. James reports.

‘The Negro in Steel’ by C.L.R. James from Socialist Appeal. Vol. 3 Nos. 88 & 90. November 10 & 24, 1939.

We must get some general conception of the role the Negro worker has played and plays in industry in this country. We have first to recognize that the race question, the color question, play their part. But we must see below the surface of things and recognize that the color question is not decisive. It is not the factor which plays the greatest part. Until we understand that, we cannot organize for struggle and plan our campaigns. We have not only to understand it but must have it deeply rooted in our minds as the basis of all our thinking. Quite recently an able study has appeared on the Negro worker. It is called Black Workers and the New Unions, written by Horace Cayton and George Mitchell. We shall use it heavily in these articles on the Negro’s role in industry, and we recommend a thorough study of the book to all workers, white and black.

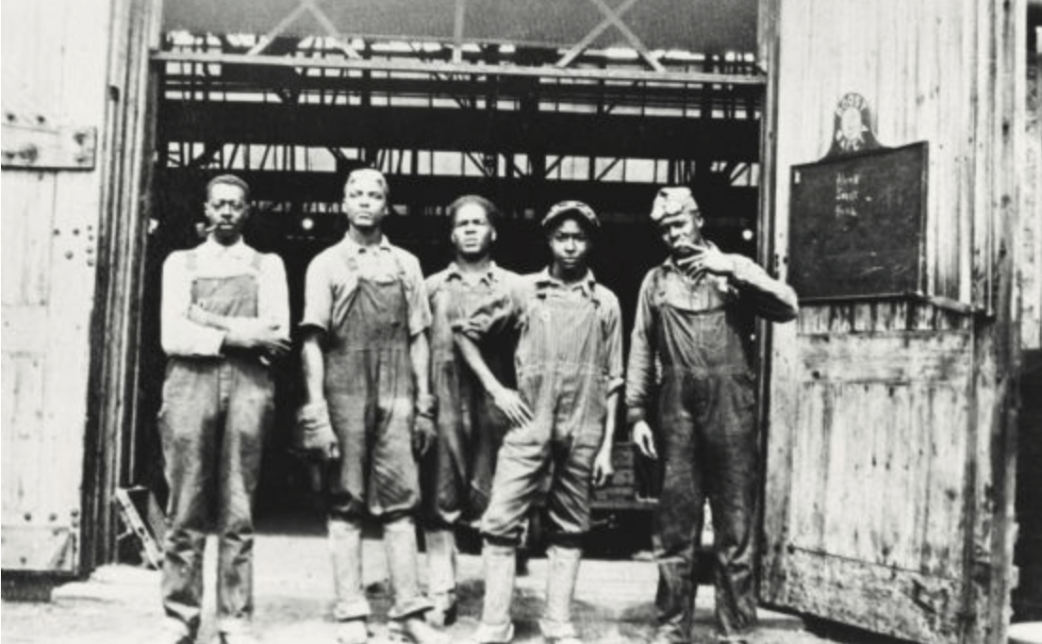

First the Negro comes into the steel industry as a strikebreaker. From 1875 to 1914, whenever the white capitalist wants to break the neck of white workers, he sends for Negroes, most often to the South, and uses them against the workers of his own color. For the great steel strike in 1919 the white capitalists brought in 30,000 Negroes. For these capitalists, the race question was certainly not the main question.

Negroes Enter Industry

This sending for Negroes to help break the struggles of the white workers was part of the general economic movement of the times – the migration of over a million Negroes to the North. Thus in the Allegheny district of Pennsylvania in 1910, there were 100 Negro steel workers, in 1915 there were 2,500, in 1916 there were 8,325, in 1923, there were 16,000.

As an official of the Carnegie Steel Company said in an interview given to Messers Cayton and Mitchell on July 6, 1934:

“As far as I am concerned I believe that the Negro has been a lifesaver to the Steel company. When we have had labor disputes or when we needed more men for expansion we have gone to the South and brought up thousands of them. I don’t know what this company would have done without Negroes.” (Black Workers and New Unions, p. 7)

On the whole, between 1890 and 1930, the number of Negroes in the iron, steel, machinery and vehicle industries, increased from less than 25,000 to 250,000.

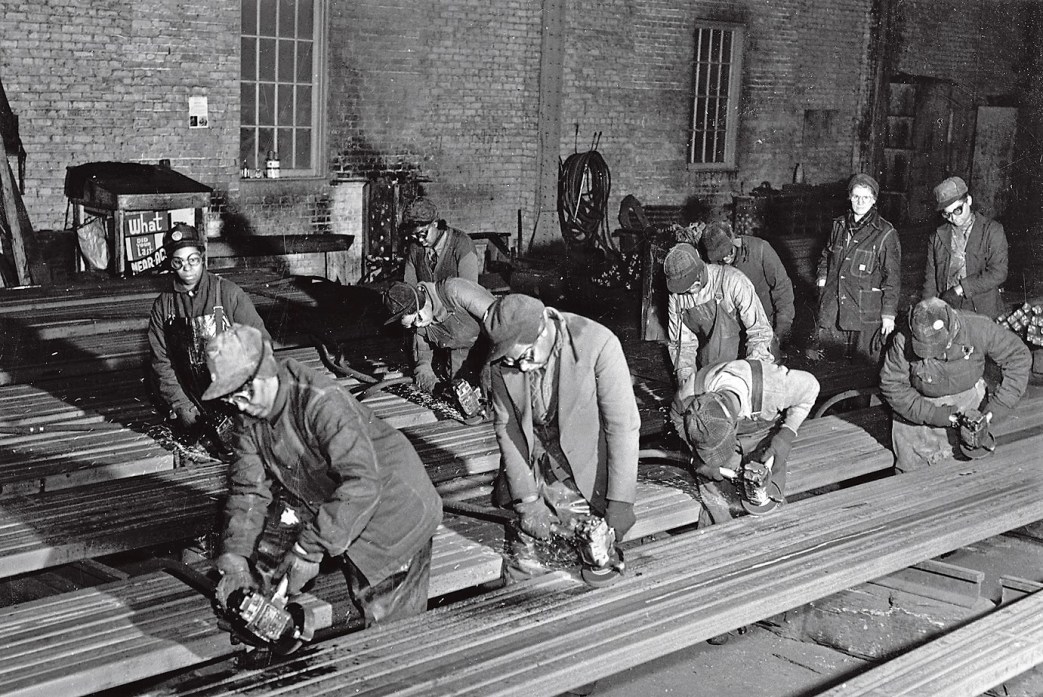

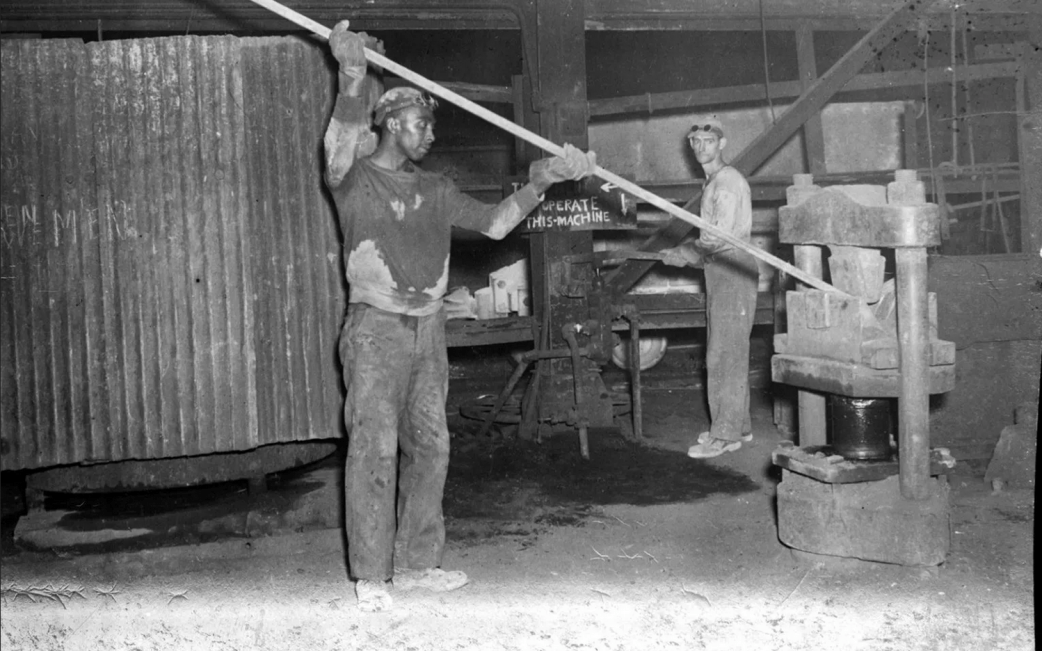

The Dirty Work for the Negro

What sort of jobs did Negroes get in the industry? Naturally nothing but the unskilled, the lowest paid, the most unpleasant jobs. Between 1910 and 1930 the Negro made little progress in getting the better kind of job. Take for instance the work in blast furnaces and steel-rolling mills. In 1910 there were between 45 Negroes out of every 1,000 working as laborers in these industries. In 1930 there were 85. Thus the number of Negroes almost doubled. But it was chiefly laborer’s jobs that the Negroes got. In 1910 out of every 1,000 laborers, 69 were Negroes. In 1930, there were 165 Negroes out of every 1,000. But whereas in 1910 there were 29 Negroes out of every 1,000 skilled workers, in 1930 there were only 40. Thus 96 more laborers got jobs, proportionally, but only 11 skilled workers. That is a point we have to keep our eye on. As for office jobs there were 3 Negroes out of every 1,000 in 1910, and only one out of every 1,000 in 1930.

All the nasty jobs are for the Negroes. But here again we must have some historical perspective. All the white groups, American born and foreign born, discriminate against the Negroes. But the American-born whites discriminate against the foreign-born whites. The American born usually take all the best jobs for themselves and the bosses encourage them. (For the boss loves, how he loves to see the workers divided.)

Discrimination Among Foreign Born

But that is not all. Even the “foreigners” discriminate. Sixty or seventy years ago Irish did all the dirty work. After a generation they moved up in the scale and the Poles, Czechs and other central Europeans did most of the dirty work in their turn. The Negroes came last into the industry and so quite naturally Poles, Czechs, and these latest immigrants did to Negroes what the Irish had done to them The bosses naturally encouraged this. The class-conscious workers tried to break it down. Only whereas the American-born, Irish, and Central European workers were all white, they could get together more quickly as workers than they could get together with Negroes.

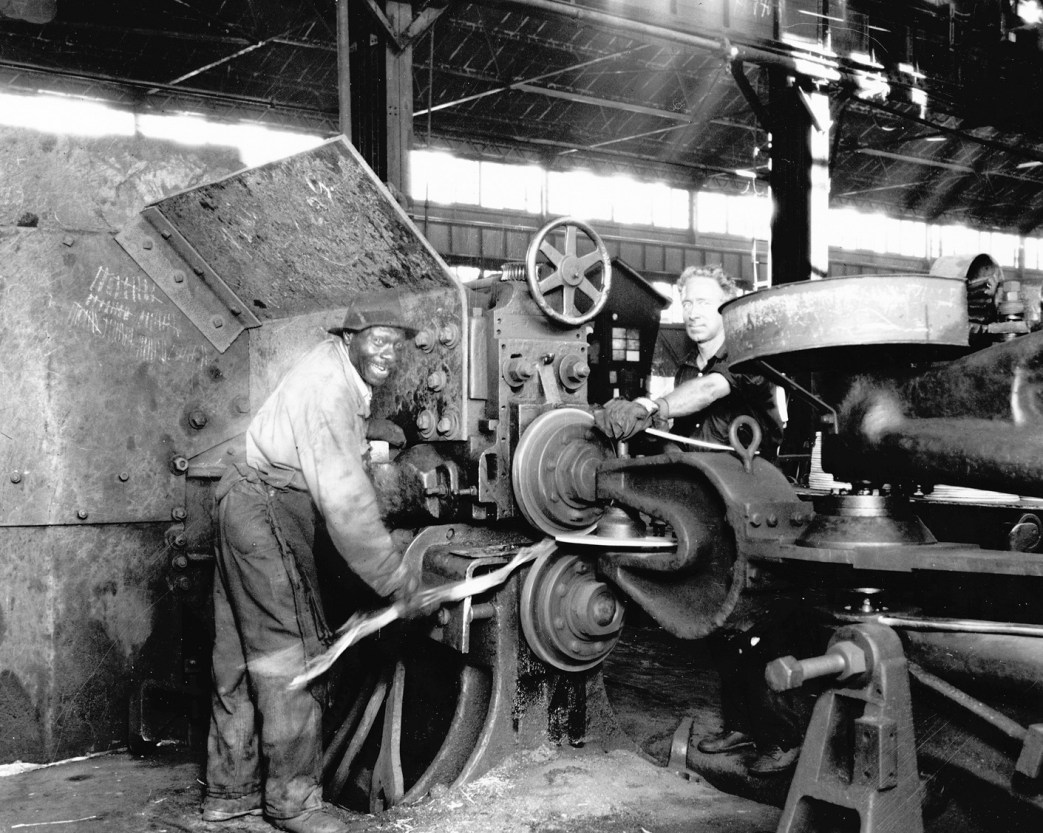

Was the Negro an Inferior Worker?

Was the Negro an inferior worker? The bosses at one time used to say so but as they found it necessary to use the Negro more and more, they changed their tune. Take this interview with a Buffalo superintendent of a steel plant:

“We found most of them good workmen. There are some who are poor, but In general they are good men. I don’t see any difference between the races.”

Or this statement by the assistant superintendent of a steel plant in Cleveland:

“Some of the very best workers we had were Negroes – I will say that the colored are on a par with the white.”

Take this from a Superintendent of Safety and Welfare in Homestead, Pa:

“The Negroes that we brought up are superior to the whites that we brought in. We got one group of whites from Kentucky Hills district. They were just the poor white trash and were no good at all. We also got a shipment of whites from around Buffalo but they were just riff-raff. The Negroes are superior to them as workmen and morally. Also I believe they are better physically.” (Black Workers and New Unions, p. 35)

Where did the white bosses learn this? They wouldn’t have said it twenty years ago. Some of them deny the Negro’s capacity up to today. But on the whole they have been driven by economic necessity to accept the Negro in the industry and then to recognize that he can do. the job as well as any other.

But the workers were having a much longer time to recognize the Negro. First it seemed to them that being white meant a better chance to get a job and a better-paid job. Which was true, though it wasn’t the whole truth. And secondly, although the white bosses were forced to recognize the ability of the Negro, they did not go out of their way to help the workers, white and black, to overcome the prejudices. For them to do that would have been suicide. It would have meant the unity of black and white workers, which, for the bosses, is the beginning of the end. So in some plants Negrotes and whites continued to be segregated in the lunch-room. In another plant the company built a swimming pool with money collected from both white and black and they prohibited the blacks from using the pool. In Gary, Indiana, the United States Steel Company took it upon itself to see that Negroes were kept out of all the municipal parks except one.

By this means the company aimed at keeping the Negroes and whites in the plants divided. The superintendent and officials of the plant actually told the Negro workers that if they used a certain park they would lose their jobs. Why? Every white worker arid Negro worker should ask himself this question and think over it until he got the answer. Why were the bosses so anxious to prevent Negro workers and their wives and children from using a park along with white workers and their families? Was it because the bosses loved the whites so much that they wanted to save them from Negro contamination? But since when have bosses been so concerned about what happens to workers after they leave work? The reason is obvious. The boss wanted to keep them apart.

Naturally the white workers should have opposed this immediately, should have demanded that the Negroes be allowed to use whatever park they wanted, should have insisted upon it. But the workers are not as quick as the bosses at seeing these things. They see them in time, however. In succeeding articles we shall see how the white steel-workers as a whole, recognized the necessity of cooperating with their Negro brothers in industry. We shall have to note particularly why they recognised it, and how this recognition expressed itself.

Let us continue with our examination of the Negro in the steel industry, as portrayed by Cayton and Mitchell in their book, Black Workers and the New Unions.

The Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers for years did practically nothing to organize the Negroes – or for that matter, anybody else. The union officials passed resolutions and talked about accepting Negro workers as well as whites, but they did nothing to bring numbers of Negroes into the union, even after the passage of the National Industrial Relations Act. The union continued its policy of equality in words and segregation in action.

But among the new unions formed after the NRA, there was a new spirit, and officers and members went after Negroes, recognizing that without them it was impossible to win victories against the bosses. Wherever the proportion of Negroes in the plant was large the workers made a determined drive. An interview with a worker in McKeesport, Penna., shows in a few words the role of the Negro in steel:

“Negroes must be organized here if the union is to have any show at all; it would be impossible to ignore them completely because of their great numbers, especially since difficulties have been experienced in bringing in the highly skilled American workers.”

Outstretched Hand Not Enough

But the Negro has behind him three hundred years of deception and exploitation by whites. Many whites make the mistake of thinking that as soon as they go with an outstretched hand to the Negro he will forget everything and accept it. It is not so easy. Many of the white workers found that they had to make a special effort to get Negroes in. One of the most frequent methods adopted was to get Negro speakers to address meetings. And certain lodges elected Negroes to offices in the unions, so as to give practical proof that the equality of which they spoke was more than verbal bait for the Negroes. In Homestead, Penna., the financial secretary of Spirit of 1892 Lodge No. 172 tells of the great success that follows the election of Negroes to office:

“… Then the rest of them came in droves. They are a clannish bunch, passing word of all such developments around among themselves. Each man brings his friends, and the next meeting the friend brings other friends, until enormous numbers of them attend in force.”

The two areas where most Negroes filed into the union were Pittsburgh and Birmingham, one in the heart of the industrial district of the Northeast and the other in the backward South. This shows us once more a lesson that we must never forget, that in the last analysis it is economic relations which are decisive in politics.

No Racial Question in Profits

The economic relation is decisive in politics. The capitalist does not allow race prejudice to interrupt his profits. When union activities became threatening, the owners in one factory tried a novel way of splitting the workers. Previously Negroes were not allowed to work the open hearth or as first helpers, but were kept as second or third helpers. To divide the working class, the company promoted several Negroes to first helpers, the most aristocratic, skilled, and well paid job in the whole mill. This had a double effect. Those Negroes who got the job would have nothing whatever to do with the union. And the other Negroes in the shop felt that at last promotion was open to them and they therefore became much cooler to union organization.

The white workers were now paying for their previous neglect of and discrimination against the Negroes. We shall see more of this in the future. But in any serious competition, on a large scale, between the workers and the bosses, the great majority of Negro workers – 99 percent of them – will find their places beside their white brothers. Economic relations, though not the whole story, are the most important part of the story.

Many of the Negro workers are sympathetic to the union. They know that they will get little from the company, but what they fear is that in the event of a closed shop the white workers might discriminate against them. This has happened in many unions and nothing but the most vigilant honesty and fair play on the part of the white workers can break down this justified distrust. Yet despite these difficulties, the unions were able to attract and to hold Negroes.

Equality Begins Among Workers

An important part of this work is the election of Negro officers. In nearly every important lodge in the Pittsburgh area this has taken place. First of all the lodges began by electing Negroes to office simply in order to attract other Negroes. Later, as more Negroes came into the union, these voted for additional colored officers. And finally all the workers, white and black, recognized the capabilities of certain among the Negro officials and voted for them without regard for the color of their skin. In Clairton, Penna., for instance, according to an interview,

“There were more colored than white elected to office. Here in Clairton there are about ten whites to one colored person. When the nomination came off, they nominated whom they wanted. We wanted to put up as many Negroes as we could. We voted by secret ballot. They had a colored man and a white man watching the ballot box. Six colored were nominated and of these, four were elected. Mr. M. was elected corresponding representative, J.E. financial secretary, M.B. trustee, and J.B. another trustee.”

When the Negro sees that he can make his influence felt and can elect some of his race to office, he can more easily turn his back on the bosses. It is in this way that the great battle for equality not only on the economic but on the political and social field will be won.

The Homestead, Penna., lodge, according to one of its officers,

“… held a couple of bingo games and a dance, all of which Negroes attended in force with their ladies. At the dance, held in the lower section of the city near the Negro district, there were no restrictions. Dancing was mixed racially and sexually, whites with Negro partners. I danced with a Negro girl myself. Negroes enjoyed themselves immensely and there was no kicks from the whites. This lodge will soon have a picnic which will be mixed.”

There are many such successful attempts, despite some failures.

This attempt of the workers to get together, naturally suffers from the tremendous pressure to which they are subjected by the race prejudices of a bourgeois society. But it is here that the battle for racial equality must be fought, and it is here that it can be won. Not in dances in Greenwich Village, or by bourgeois hosts and hostesses who invite intelligent Negroes to their houses for dinner in order to show that they are enlightened and above the vulgar prejudices of capitalist society. Some of these people mean well, some of them do not. But their activities, their parties and lunches are a mere drop in the ocean. They are not important. Black and white workers struggling together for socialism will bring equality, and nothing else will.

There have been a number of periodicals named Socialist Appeal in our history, this Socialist Appeal was edited in New York City by the “Left Wing Branches of the Socialist Party”. After the Workers Party (International Left Opposition) entered the Socialist Party in 1936, the Trotskyists did not have an independent publication. However, Albert Goldman began publishing a monthly Socialist Appeal in Chicago in February 1935 before the bulk of Trotskyist entered the SP. When there, they began publishing Socialist Appeal in August 1937 as the weekly paper of the “Left Wing Branches of the Socialist Party” but in reality edited by Cannon and other leaders. Goldman’s Chicago Socialist Appeal would fold into the New York paper and this Socialist Appeal would replace New Militant as the main voice of Fourth Internationalist in the US. After the expulsion of the Trotskyists from the the Socialist Party, Socialist Appeal became the weekly organ of the newly constituted Socialist Workers Party in early 1938. Edited by James Cannon and Max Shachtman, Felix Morrow, and Albert Goldman. In 1941 Socialist Appeal became The Militant again.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/socialist-appeal-1939/v3n88-nov-17-1939.pdf