There is, perhaps, not a better to person to tell this history than Angelica Balabanoff. Working closely with Mussolini from his 1902 joining the PSI in Swizterland, where Balabanoff was then living, through their collaboration on ‘Avanti,’ and the politics of the PSI’s ‘Maximalist’ wing. At the writing of this article, first published in Living Age in 1926, Balabanoff had left the Communist movement in 1922 and had returned to the PSI to lead its revolutionary ‘Maximalist’ faction.

‘When Mussolini Was a Socialist’ by Angelica Balabanoff from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 4 No. 56. March 19, 1927.

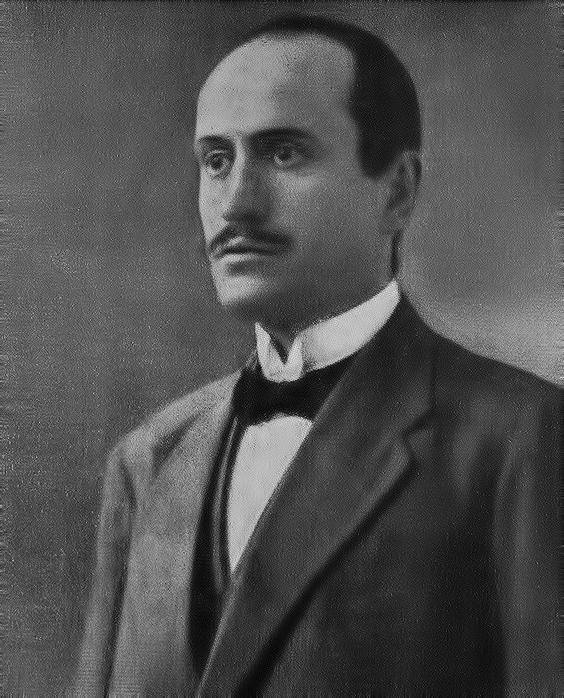

I made my first acquaintance with Mussolini in 1906 on the occasion of my speech to the Italian Socialists immigrated to Losanna (Switzerland).

At that time he was a young man of 22 or 23 years of age and drew my attention for his aspect of extreme poverty and penury.

Even then he had an uneasy agitated appearance, like a man who suffers of some hereditary disease. I thought to myself: “This one is some poor persecuted proletarian who may be in need of a soothing word,” and I asked him who he was and whence he came,

Mussolini told me that he had fled from Italy because he did not want to serve in the army. He was in a grave pecuniary need and lived mainly by aid offered him by the masons and diggers of Losanna.

One of these masons then told me that his wife had given him some old underwear. It was in this manner that these Italian immigrants, many of whom were poor occasional workers, aided a refugee who had studied for school teacher, but had not had the capacity to continue at this profession.

Mussolini is the son of a poor worker, a blacksmith who lived in Piedappio, near Foili, in Romajna. His father was a socialist and a member of the First International. Mussolini therefore was “brought up in a socialist environment.

The peasants of his village belonged to the party and Mussolini being a man of the sort that adapts himself easily to the ideas of those who surround him, he also became a member of the party.

In my first conversation with him he told me that he had a strong desire to translate “On the Morrow of the Social Revolution,” by Kautsky, because he would have been able to earn thereby about 50 francs. I offered to help him and when I returned to Losanna I made a great part of the translation for him because at that time he knew very little German. He had no regular trade so he read a lot and particularly French authors like Blanguin and he thus filled his brains with the thoughts of French writers. He had always been a man of a strong adaptability of thought and he possessed—besides that faculty of assimilation common to so many Italians—a nervous system of an abnormal impressionability.

Until 1900 we published in Losanna, a socialist paper which still exists, called “L’avenuire del Lavoratorie,” (The Workers’ Future) to which I collaborated from time to time. Mussolini began to contribute articles to this paper many of which were on anti-clerical and anti-militaristic subjects.

His anti-clericalism was of a very primitive type. He never gave a scientific interpretation of religious problems, but he attacked the church as an institution.”

At this time he also published a pamphlet in which he attempted to prove the non-existence of god. It is one of the many ironies of history that this pamphlet is now forbidden in Italy by order of the Prime Minister Signor Mussolini.

A few years later, I think in 1909 or 1910, Mussolini was arrested and returned to Italy where he become the director of one of the two hundred or more socialist weekly reviews and especially the one called “The Class Struggle.”

At that time he often invited me to speak where he was and I remember having once spoken in Forli on the Paris Commune. It was a lively meeting. The bourgeoisie of that locality were all republicans and the peasants all socialists, so the camp was divided into two opposing parties. The republicans attempted to disturb my speech with a bowling match in a wine shop close to the place where I was to speak. Mussolini Was terribly agitated. I was not disturbed and spoke nevertheless. But when I had finished Mussolini informed me, trembling with emotion that a quarrel had taken place and that a socialist had stabbed a republican.

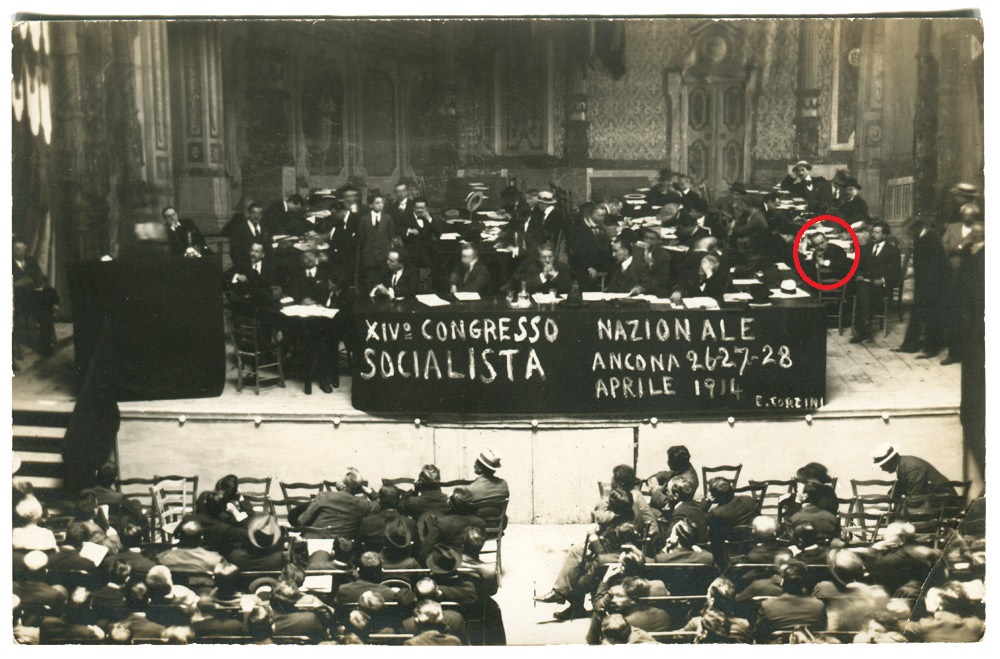

I remember well that Mussolini’s agitation was due not so much to the sentiment of responsibility for this unfortunate accident as to the fear of unpleasant probable consequences for himself. When the meeting was over we went in a cab towards the station. Mussolini insisted desperately on having carabineers escort and protect us. So a part of the latter preceded us in a cab and others marched beside us. We scarcely had moved when a detonation was heard. They had shot at us but they struck the first vehicle full of carabineers. Mussolini was seized by a deadly terror and pitifully implored me not to leave the town. He did not have the heart to remain alone. No one knew what could have happened. I told him that I couldn’t remain because on the morrow, being the first of May, I was engaged to speak elsewhere. But Mussolini continued to disavow me until we reached the station platform and I finally left him after which our comrades promised to protect him personally. At the socialist congress of Reggio Emilia, the radical socialists, to which Mussolini belonged, bad a majority over the reformists, whose leaders were expelled from the party on Mussolini’s proposal. AH the other reformists then went out of the party and were replaced by official radicals including myself and Mussolini, who was elected representative for the province of Romajna.

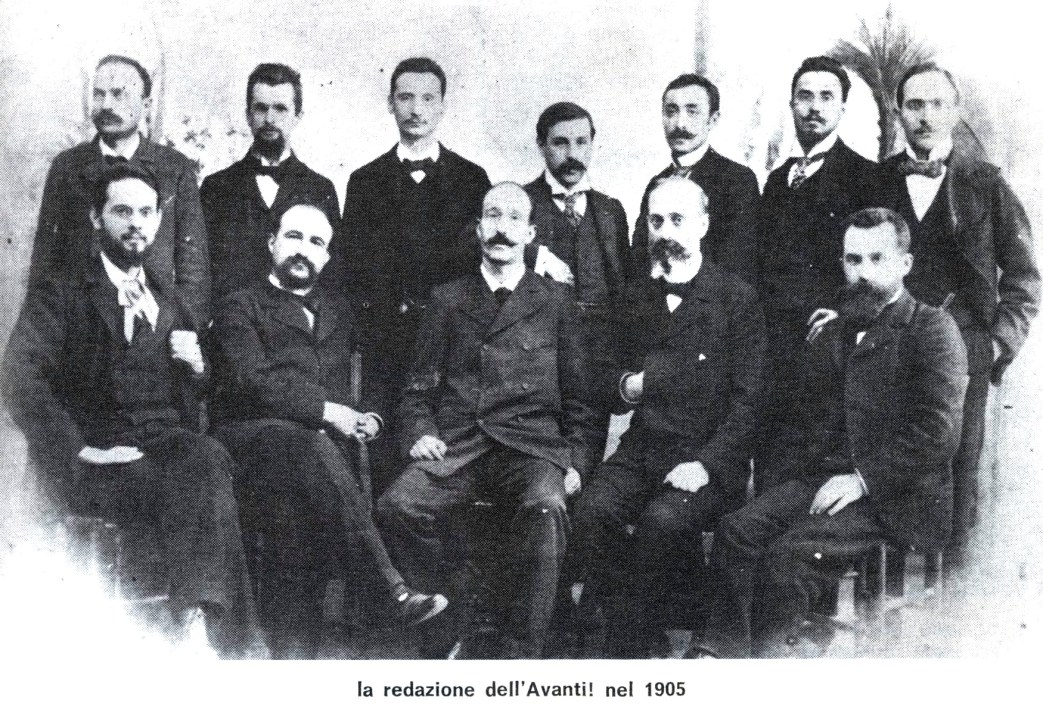

It was on this occasion that Mussolini provoked the expulsion of Bissolati from the party because the latter went to congratulate his king for the failure of the Hemft to murder him at Alim. Some months afterward Bacci, editor of the “Avanti!” our organ at Milan, was obliged to resign from the party. The executive of the party assembled in Rome and Mussolini was proposed for the editorship. Some objections were raised that he was too individualistic and did not observe enough the party discipline.

Before the affair was decided we had a separate encounter and at dinner Mussolini told me that he felt little disposed to accept this position so full of responsibility. But at the afternoon session he unexpectedly declared to accept, but on only one condition, that I go to Milan with him to assist him. This happened only a few minutes after we had been to dinner, together, and even during all that time, he never spoke to me about it. Evidently he meant to take me by surprise. I consented, having considered Mussolini as a weakling who was in need of help and advice, and thought it my duty as a socialist to aid him. But even though I considered him a weakling, I thought he was loyal to the party and a convinced revolutionary, and even today I believe that such were his sentiments at that period. In the editorial room I worked beside Mussolini several hours of the day and learned to know him intimately.

His bad humor derived from the fact that he was not in Milan willingly, alone; and was obliged to have some one with him to share the responsibility and this thing impressed me so much the stronger the more we were together.

He spoke to me of everything, and wished that I read every important article before sending it to the press. He never spoke much to the other members of the directors and was reserved with them and held them at a distance.

But he let himself be influenced easily.

Once—this happened on the eve of a May Day. He called me, agitated, to show me an article which he had written against a syndicalist who attacked him personally. This article had been written in such a violent form that I told him that it did not seem suitable for the “Avanti!” especially for May Day.

Mussolini, all agitated, said that it was for him a question of life or death to redeem himself with this comrade. He wanted to have his revenge now that he was in a position to do it because this-man exposed himself by attacking gratuitously. Then he quickly bid me good-bye, adding that he was going to leave for Switzerland on the 1st of May.

Half an hour later he phoned me from the station: “You are right. That article for the ‘Avanti!’ does not go. Do me a favor not to let it pass.”

Mussolini is physically timid.

Every night he begged me to wait until the paper came out, not to go home alone. He was afraid to go out unaccompanied. When once I asked him of what he was afraid he answered nervously: “I do not know; of myself, of my shadow, of the trees, of the dogs.”

So I used to stay with him until 4 a.m. and go with him to the doorstep of his home. At first I asked myself why he always wanted me as a companion, but soon discovered that he was much ashamed of his fear and above all he did not like to confess it to any other man. One day Mussolini returned from a tour of propaganda very ill and told me that he could not bear it any longer, that for him it was ended, because he was affected of an incurable disease. And he spoke to me of himself with remarkable frankness, though in a decent manner. I advised him to go to some medical authority to be thoroly examined. On the morrow he came very pale to the office, accompanied by a doctor. He told me that be felt nauseated to have to always smell of chloroform, that the doctor had pinked him to analyse his blood and that he fainted during the operation. I spoke to the doctor who told me he was at the head of a clinic in Milan and that he had cured several thousands of clients, but that he never came across a man that demonstrated so much physical timidity as Mussolini.

Another weakness in Mussolini, which indicates the same nervousness and lack of decisiveness, is his inability to say no.

Once, with the same kind of excitement, he told me that one of our comrades would arrive that evening and that he was the strongest man in the Socialist Party. This comrade wished that Mussolini, as directing member of the party, approve a proposition to be submitted to the executive committee. Mussolini did not approve it but did not wish for the time being to say no to this man and begged me to say it to him. This comrade came at 10.30 and discussed the tiling with me till 4 o’clock in the morning. When he left, without my consent, Mussolini told me that he could not conceive how I had managed to resist his insistence. The day after, at Genoa. I met this comrade who cheerfully told me that he had obtained what he desired. He never had gone to see Mussolini at his address and had persuaded him to give his approval in writing.

Things continued in such away until 1914.

In August of that year Mussolini who, as usual, reflected the sentiment of those by whom he was surrounded, was an ardent internationalist and antimilitarist. He had read in a socialist review that if the war had been prevented it would have bee as disaster, because it would have weakened the socialist movement. So for many months after the beginning of the war. he defended this opinion, not because he Conceived it himself hut because it had been suggested to him. In that period the sentiment against intervention in the war were only to the proletariat. Notwithstanding, confined the spirit of war began to lie diffused rapidly among the middle classes and to also infect Mussolini. But he published his first declaration in favor of the union with the allies in a bourgeois paper through a friend’s intervention.

This article which wanted to demonstrate that the Socialist Party was not unanimous about the tear and which showed how a member of the executive was in favor of Italy fighting on the side of France, caused tremendous indignation.

The Party executive immediately organized a conference at Bologne where Mussolini was called to defend his action. On the eve of this encounter he published an article in the “Avanti!” in which he revealed openly his change of front. He held that Italy should intervene in the war with the western powers and he Was evidently anxious to engage the party on this read before the conference took place.

We went to Bologne together in November, 1914. I read the article on the train and said to Mussolini: “If you have written this you must either go and engage yourself in the army or in an insane asylum. You certainly must not expect to remain in the party.”

Mussolini answered twistingly: “The whole Executive Committee will be with me.”

Evidently he deceived himself, because the party was a whole unit against him.

I never shall forget this conference at Bologne. It was one of the worst tragic scenes that I’ve ever seen.

One after the other the members of the Executive Committee came on the platform and condemned Mussolini’s attitude.

He remained silent, gloomy, irresolute, with a wandering look, like a man accused of a crime. Finally I spoke and said that he should reconsider his position, not because be was indispensable to the ‘Avanti!’ but because he was on the wrong track.

Mussolini did not reply until the Executive Committee had voted unanimously to fire him from his post. I then made a motion asking to give him some money.

Then he rose and said in a rude and villainous manner. “I do not want anything. I’ll throw away my pen. I don’t want to write anymore. I want to return to my trade as a mason for 5 lires a day.” But the truth was that be had already received funds for a paper in which Mussolini would be free to preach war.

At this congress he gave me the impression of a man terrified by his own bad conscience.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to ‘New Magazine, and again to the Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1927/1927-ny/v04-n056-new-magazine-mar-19-1927-DW-LOC.pdf