‘Hanns Eisler, Maker of Red Songs’ by Ashley Pettis from New Masses. Vol. 14 No. 9. February 26, 1935.

SINCE the advent of Hitler to power, many celebrated German musicians have taken refuge in America. For obvious reasons they have remained strangely inarticulate in the midst of their exile, in spite of the fact that they all unquestionably have much to say and many are known to possess definite social consciousness. The fear of reprisals upon relatives remaining in Germany has been responsible for the silence of some.

This fear of the Hitler terror is so great in the minds of the refugees, that one world famous musician explained to me, upon saying he could not talk for publication, “And above all things, do not write that I said I cannot tell anything!”

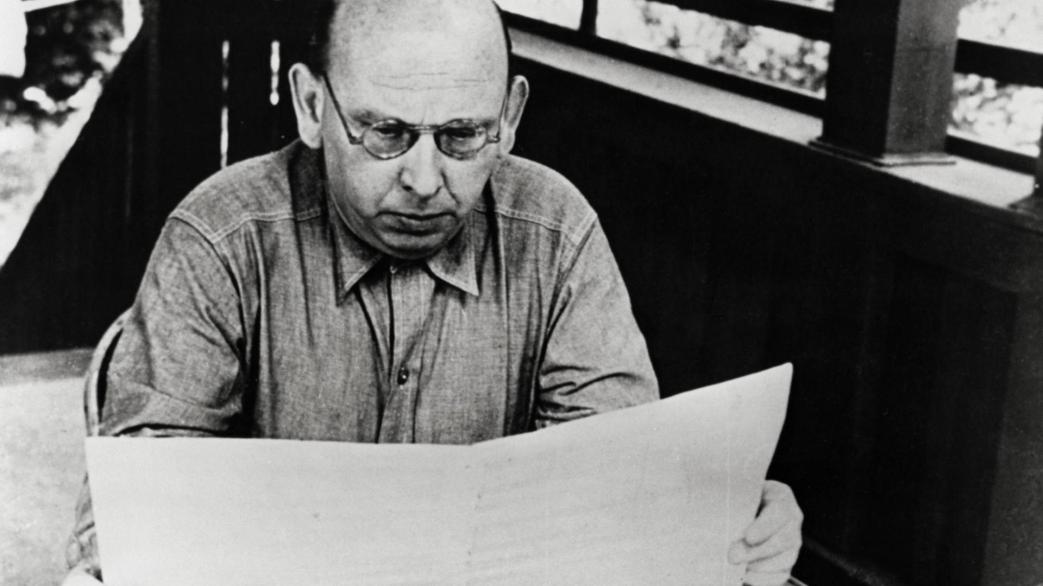

The attitude of Schoenberg, one of the most influential of modern composers, was quite another matter. Typical of the “artistic” head-in-the-clouds attitude, pretending to himself and others, that he was completely cut off from mundane concerns, he declared, that the composer is unconcerned with socio-political matters-he merely goes ahead with his work. Schoenberg’s compositions bear eloquent evidence of his state of mind and the atmosphere in which he works. But with the arrival of Hanns Eisler, the famous revolutionary German refugee composer, one is confronted by what is no less than a phenomenon in contrast to the musician type mentioned above.

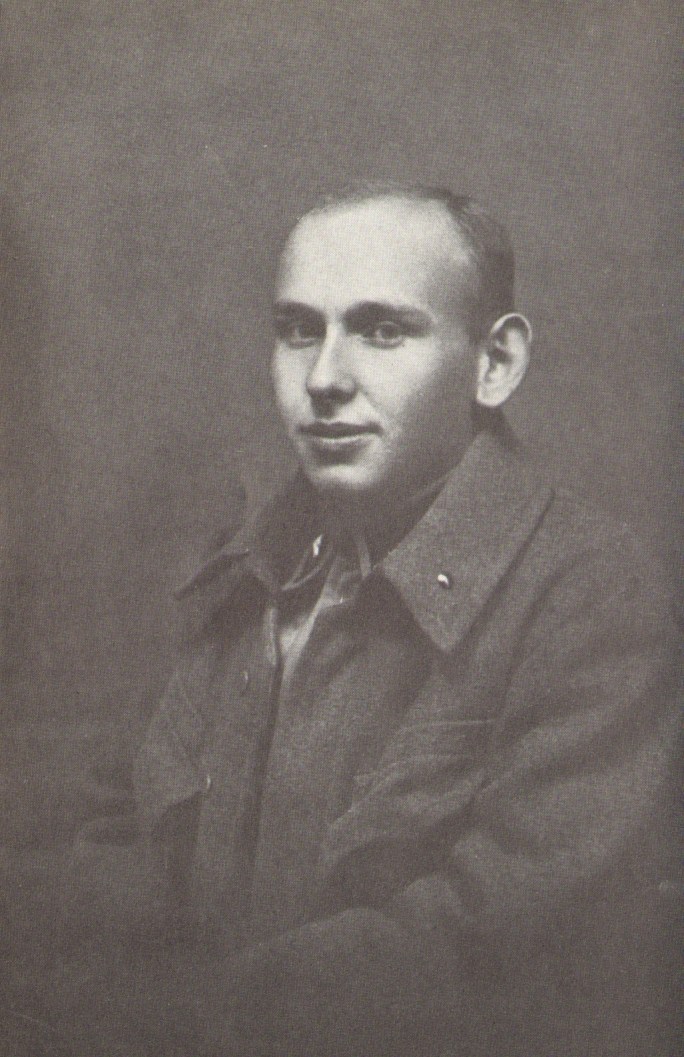

Hanns Eisler is far from being a “late arrival” in the revolutionary field. Born in 1898, in Leipzig, he was raised and educated in Austria. At the outbreak of the World War, although hating and protesting against war, he was compelled to enter the Austrian army, in which he served until 1918. Still a very young man-only twenty years of age he returned to civilian life in a world of poverty and chaos. Largely self-taught up to this time, he became a pupil of Arnold Schoenberg, who has had a far-reaching influence upon many leading composers. Eisler’s training under Schoenberg was extremely valuable for background and foundation. During this period he composed chiefly for esthetes and the socially elite.

But a growing awareness of social reality and of the vital considerations facing the sincere artist soon forced him to abandon his esthetic compositions and the Schoenberg school. As Eisler himself says:

“I was faced with the reality of composing for the millions . . . and a complete change in my method of composition …. It meant facing a problem of completely re-educating myself and entering a new period of study.”

Undoubtedly his attitude toward the war, as well as his participation in it, had prepared him both in ideology and action, for work with the masses. His social consciousness had been greatly stirred by Karl Liebknecht. Hence he emerged, not a detached musician, but one prepared in every fibre of his being to build a new type of music for the working class. In 1926 he moved to Berlin, where he became active in various workers’ organizations. But what concerns us primarily is the enormous influence and popularity Eisler has attained throughout the world for his creation of mass songs for the working class.

Eisler spoke at length on the expulsion of the finest musicians from Germany, not only Jewish artists, but many whose only crime was their unwillingness or inability to conform to the stifling restrictions of the Nazi philosophy. He pictured the cultural collapse of Germany-all the more appalling because of its former high cultural level. He talked at length of Hindemith – an outstanding German composer of modern times. Hindemith has long been changing in his · ideology from the traditional, false attitude of “music for music’s sake,” realizing the necessity for expanding the social functions of music. He was a modern “materialist” musician, but not a dialectical materialist. He was unable to give in to fascist tendencies. For a time he even tried to curry favor with the Nazi regime by his religious, mystic opera Mathias der Maler, which did not serve to bring him closer to fascism for the moment. The total collapse of German culture was in itself not a greater calamity than the discouragement of the younger generation of German composers, epitomized in the treatment accorded Hindemith, who was the greatest influence in their lives. They now have recourse only to the ultra-reactionary tenets of non-productive Nazism, to the romantic musical standards of 1880. Richard Strauss alone of the musically great of Germany remains in his dotage, impotent, completely acquiescent, unquestioning, unprotesting in the face of expulsion of his most illustrious colleagues; a relic of imperialist Germany – a perfect Nazi! Concerning Arnold Schoenberg and his place in modern music, Eisler made the following statement:

“Schoenberg is my teacher. I am immensely thankful to him for what he has done for me. I consider him the greatest modern bourgeois composer. If the bourgeoisie does not care for his music, I can only regret this fact, for they have no better composer. Schoenberg’s music does not sound beautiful to the uninitiated listener, because he mirrors the capitalist world as it is, without beautifying it, and because out of his work arises the visage of capitalism, staring us directly in the face. Because he is a genius and a complete master of technique, this visage is revealed so clearly that many are frightened by it, Schoenberg, however, has performed a tremendous historical service, in that the concert halls of the bourgeoisie, when his music is heard there, are no longer charming and agreeable pleasure resorts where one is moved by one’s own beauty, but rather places where one is forced to think about the chaos and ugliness of the world, or else, to turn one’s face away.

“Schoenberg has performed another great service, as the teacher of generations of young composers. For a long time yet, one will be able to learn from his works, even when they will no longer be listened to for enjoyment. In another domain, Einstein’s theories, although they are of no practical use in the immediate present, are historically of great significance. So with Schoenberg; for the past forty years his versatility has been of such significance that we who do not share but reject his political opinions, can admire him as an artist. It is as Marx puts it: “No matter what he thinks about his own situation, or what his views are-the important thing is to study his actual work, that which he has concretely done.” Therefore we can say that Schoenberg’s production is historically the most valuable production of all modern music. Young composers, and above all, young proletarian composers, must not listen to and copy him uncritically, but they must have the strength to differentiate the content of his work from the method.

“That this man, sixty years old, and no longer in good health, after a life full of the severest privations undergone for the sake of his art, should be driven homeless throughout the world, is one of the most frightful shames of capitalism in the sphere of culture today.

“One will always learn from him, when other composers, who are today fashionable, will have been long forgotten.”

The masses of American workers together with the intellectuals have a great opportunity to express in practical action that word which is so frequently used: Solidarity– onewhich Eisler has so eloquently set to music. His songs, which are sung by the masses the world over, in the Soviet Union-even to distorted words in the camp of the enemy-in France, England, the United States-wherever workers are uniting in common cause, are to be performed at a concert to be held at Mecca Temple, Saturday evening, March 2, at 8:15. A great chorus of 1,000 voices, made of worker’s choruses, was rehearsed by Eisler himself.

On this occasion a new and remarkable composition, which Eisler has just procured, will be performed for the first time. It is a song, the words and music of which were written in a German concentration camp by a political prisoner. It is of the utmost simplicity, so much so that Eisler remarked he could teach it to all present in five minutes. We hope he will do this.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v14n09-feb-26-1935-NM.pdf