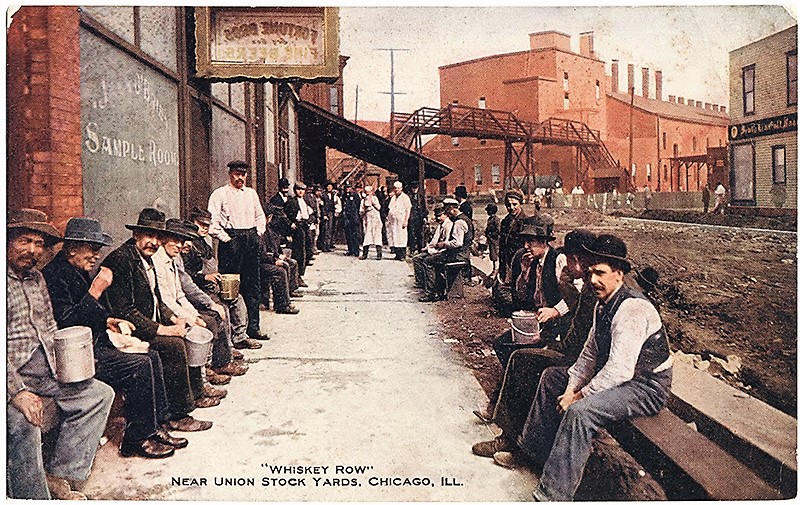

An important and valuable article on the history of William Z. Foster’s labor activities and the larger history of the U.S. labor movement. This in depth essay traces the past failures to organize the powder keg of Chicago’s massive meat packing industry, employing many tens of thousands of diverse workers. Beset by craft union conservatism; degrading conditions with high turn-overs; AFL reluctance; gender disparities and sexism; language barriers and native-born xenophobia, and the largest impediment, violent racial divisions rooted in white racism carefully fostered by the employment of Black strikebreakers and wage differentiations (sometimes more for Black strikebreakers, always less for regular Black workers). The failure of the Stockyards Labor Council campaign, started in 1917 by Foster and others, admittedly sabotaged from many forces, including the AF of L, to overcome those divisions was catastrophic. While certainly not the sole reason, it failures could not help but play a part in the severe white pogroms against Black workers, largely centered on the yards and meat packing industry, that swept Chicago in 1919, killing dozens, wounding and displacing thousands, and setting back unionization by a generation or more.

‘How Life Has Been Brought Into the Stockyards’ by William Z. Foster from Life and Labor (National Women’s Trade Union League). Vol. 7 No. 4. April, 1918.

A Story of the Reorganization of the Packing Industry by William Z. Foster, Secretary Chicago Stockyards Labor Council.

The main questions, touching wages, hours and conditions of labor, involved in the Stockyards arbitration hearing before Judge Alschuler, and his decision concerning them, are of overwhelming importance, both in principle and in consequence. Just how far-reaching will be the results of the decision one cannot now forecast. But lips stiffened by poverty will perhaps now learn to smile, and thousands of families will for the first time taste of life.

EIGHT MONTHS ago the vast army of packing house workers throughout the country were among America’s most helpless and hopeless toilers. Practically destitute of organization, they worked excessively long hours under abominable conditions for miserably low wages. Hope for them indeed seemed dead. But today all this is changed. Like magic splendid organizations have sprung up in all the packing centers. The eight hour day has been established, working conditions have been improved and wages greatly increased. From being one of the worst industries in the country for the workers the packing industry has suddenly become one of the best.

The bringing about of these revolutionary changes constitutes one of the greatest achievements of the Trade Union movement in recent years. A detailed recital of how it occurred is well worth while.

Since the great, ill-fated strike of 1904 the packing trades unions had put forth much effort to re-establish themselves. But, working upon the plan of each union fighting its own battle and paying little or no heed to the struggles of the rest, they achieved no better success than have other unions applying this old-fashioned and unscientific method in the big industries. Complete failure attended their efforts. No sooner would one of them gain a foothold than the mighty packers, almost without trying, would destroy it.

The logic of the situation was plain. Individual action had failed. Possibility of success lay only in the direction of united action. Common sense dictated that all the unions should pool their strength and make a concerted drive for organization. Therefore, when on Friday, July 13, 1917, exactly thirteen years after the calling of the big strike, Local No. 453 of the Railway Carmen proposed to Local No. 87 of the Butcher Workmen that a joint campaign of organization be started in the Chicago packing houses, the latter agreed at once. The two unions drafted a resolution asking the Chicago Federation of Labor to call together the interested trades and to take charge of the proposed campaign.

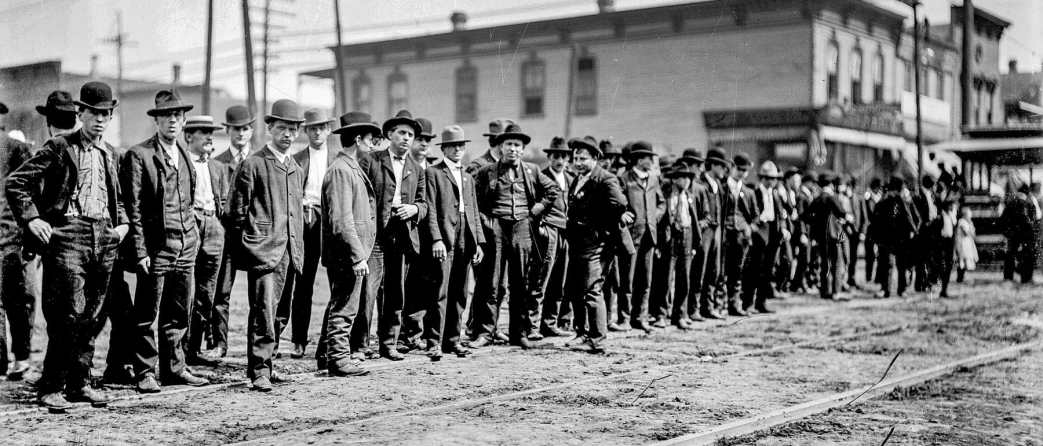

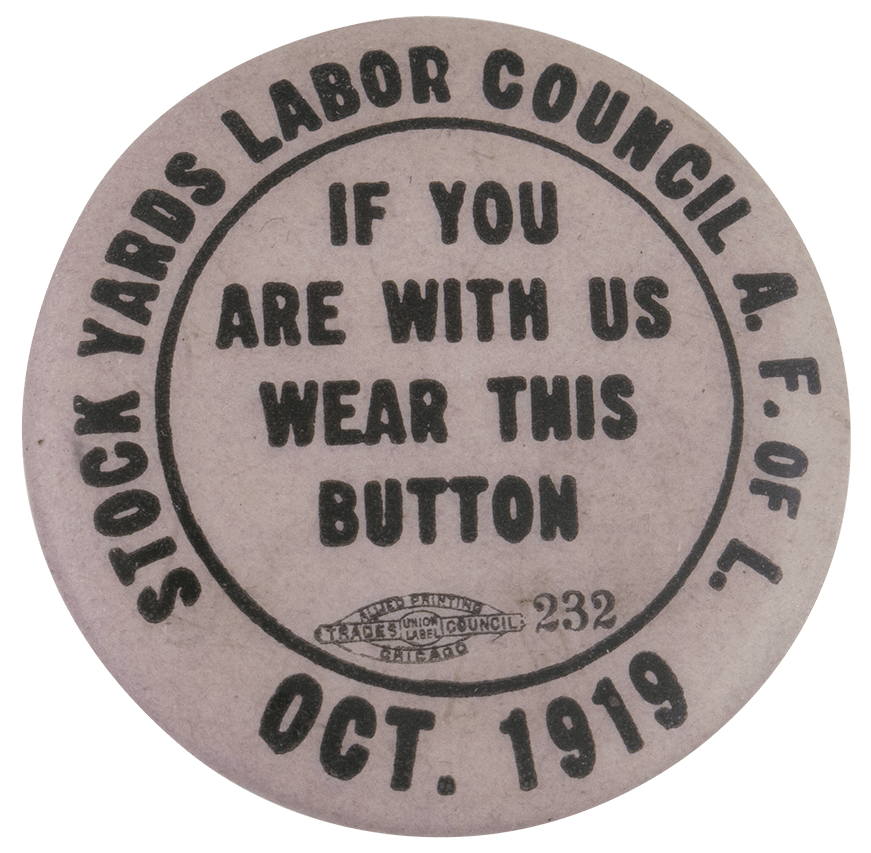

Thirteen years of unbroken defeat had convinced almost everyone that it was utterly impossible to organize the 60,000 Chicago packing house workers. But upon the proposal of the new plan of joint action the Federation, with an unconquerable faith in the power of unionism, threw itself wholeheartedly into this latest effort. The resolution passed unanimously. Then President John Fitzpatrick took hold in dead earnest. Throughout the entire movement his able assistance was invaluable. He first assembled representatives of all local organizations having jurisdiction over packing house workers, including the butchers, blacksmiths, coopers, colored laborers, egg inspectors, electrical workers, horseshoers, journeymen barbers, leather workers, machinists, office employes, painters, railway carmen, sheet metal workers, stationary firemen, steam engineers, steam fitters, structural iron workers, switchmen, teamsters and women workers. Many of these unions hadn’t even one member in the Stockyards, but on July 25th they were drawn up together into a permanent body, the Stockyards Labor Council, and given the big task of organizing the multitude of oppressed and defeated packing house workers.

SOME INTERNAL PROBLEMS

From its inception the Stockyards Labor Council proceeded on the theory that success in organization work depends almost wholly upon the strength and intelligence of the organizing force. It scorned the idea that any workers are “unorganizable,” considering such a conception to be merely an excuse for Trade Union incompetence to hide behind. It knew that if it could make a sufficiently powerful appeal to the workers the latter were bound to respond, be they never so defeated and discouraged. Therefore, the Council felt that its really big task was to organize itself rather than the packing house workers. Its problem was chiefly internal, not external. If it could succeed in creating an effective organizing force the actual bringing of the immense army of workers into the unions was bound to ensue.

With this right-side-up conception of its problem before its eyes the Council turned in upon itself and began to organize. Its first job was to bring about the indispensable community of action between the score of affiliated unions. But how was it to be done? Some advocated a continuance of the old tactics of individual action, counting for success upon the added volume of effort. Others flew to the opposite extreme and demanded straightout industrial unionism. Finally, after much travail, the solution was found in the federation plan, which has proved so successful on the railroads. But before it could be established and the organizations welded together into one body the permission of a dozen internationals had to be secured.

The next problem was the negro question. This was serious. About 12,000 colored workers are employed in the Chicago packing houses. They work in all the trades. To organize them was imperative. They were very suspicious and distrustful of the unions, due largely to the propaganda of the packers. The fact that many of the organizations drew the color line was enough to ruin the whole proposition. The difficulty had to be gotten around or inevitable failure would result. A place had to be made in the movement for every negro in the packing houses. The situation was laid before President Gompers. He grasped it at once and agreed that, provided no serious objections were raised by the internationals involved, special charters should be granted to colored workers engaged in trades where they were barred by the regular unions. This liberal measure removed a great obstacle to the organization of the packing house workers.

THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS

Finally, after eight weeks intensive organization of itself, the Council felt ready to enter upon the second stage of its big undertaking, to actually bring the workers within the folds of the unions. All the affiliated organizations had been combined into a harmonious whole and infused with a do-or-die spirit. A place had been found in the ranks for every man, woman and child working in the packing houses. A competent corps of organizers had been assembled, two of whom, colored men, were coal miners, whose services were donated by the Illinois miners. Then, on September 9th, the organization campaign began with a roar. Rarely had it been equaled in this country. For weeks huge hall and street meetings, parades, automobile demonstrations and smokers followed one another in rapid succession. Over 500,000 pieces of literature, in various languages, were distributed.

Then the inevitable happened. Gradually the workers aroused from their lethargy. In organization they began to see relief from their poverty and oppression. Due largely to the splendid work of John Kikulski, A. F. of L. Polish organizer, the great army of laborers first began to move. Then came the skilled trades. To begin with the workers came slowly. Then, as their confidence rose, they came in a mighty flood. As many as 1,400 joined at one monster meeting. The organizers were swamped. The opposition of the companies was fruitless. Increasing wages and working hardships upon the unionists alike proved powerless to stem the swelling tide of organization. A living torrent poured into the unions. This continued for weeks until, finally, after thirteen long years of bitter struggle, Organized Labor found itself again firmly intrenched in the packing industry. A paean of joy rose spontaneously in the heart of every Chicago unionist.

Meanwhile, while these stirring events were transpiring in Chicago, a veritable storm of organization raged in the packing houses all over the country. Strikes broke out in Omaha, Kansas City and Denver. All were successful and left good unions. In St. Joseph, St. Louis, St. Paul, Fort Worth and Oklahoma City the organizers of the Butcher Workmen had remarkable success. Everywhere the workers joined en masse. The movement of the packing house workers was no longer local, but national.

THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT

By the first of November, less than two months after the actual campaign of organization began, the demoralized and “unorganizable” packing house workers had responded so splendidly that the situation was deemed ripe for the unions involved to make a nationwide move for better conditions. Therefore, on November 11th, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen held a national conference in Omaha. They mapped out demands for the eight hour day, substantial increases in wages, equal pay for men and women, etc. This gathering was followed, on November 13th, by a conference in Chicago of representatives of all the international unions most heavily interested in the packing industry, including the Butcher Workmen. This conference adopted practically the same demands as those established at the Omaha meeting. All the organizations pledged themselves to stand loyally together in the big fight looming up.

The next step was to deal with the five big packers—the rest were to be handled later. To this end a committee was appointed, consisting of John Fitzpatrick, President of the Chicago Federation of Labor; Dennis Lane, Secretary-Treasurer of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, and the writer. This committee bearded the autocratic packers in their dens. But it made no progress. The packers refused point blank to have anything to do with the unions. And then, as if to make their refusal the more emphatic, the Libby, McNeill and Libby Co. (a Swift concern) discharged fifty-two men for belonging to the union.

GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION

This at once created a serious situation. For the unions it was a case of fight or die. They chose the former. On Thanksgiving eve a strike vote was put out to all the trades in the nine big packing centers of the Middle West. This carried by a 98 per cent vote, 75,000 packing house workers expressing their determination to strike if no other solution could be found. A telegram was sent to the officials of the A. F. of L. advising them of the action taken. They notified the Department of Labor and a mediator, Fred L. Feick, appeared upon the scene.

Mr. Feick asked that every effort be lent him to prevent a tie-up of the vitally essential packing industry. He proposed that a truce be declared till the Government could look into the situation. This the unions, wishing to cooperate in every way with the Government, readily acceded to, but not until the packers had been compelled to reinstate all the discharged men. Mr. Feick then sought to bring about a meeting between the union committee and the packers. But he failed completely, the packers still maintaining their autocratic position of refusing to give their employes any consideration whatsoever.

A NEW CRISIS

Seeing that the packers paid no attention to the appeals of the Government to settle the trouble peaceably, Mr. Feick left for Washington to report to his superiors. This brought on a fresh crisis for the unions. In a number of recent Chicago strikes Government mediators have intervened, been defied and ridiculed by the employers and have had to pack their grips and depart, leaving the workers infinitely worse off than if the mediators had stayed out of the affair altogether. In such cases the workers naturally conclude that if the Government can do nothing with their autocratic employers it is useless for them to keep up the fight, and a lost strike results. Therefore, when Mr. Feick, following the example of so many other mediator, prepared to leave after his unsuccessful efforts the unions had to act, under penalty of seeing the very ground cut from beneath their feet. They decided that they, too, would go to Washington. They determined to lay the whole matter before the officers of the A. F. of L. for their consideration and action.

A committee was formed. It consisted of representatives of the Illinois Federation of Labor, Chicago Federation of Labor, Stockyards Labor Council, Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, International Brotherhood of Blacksmiths and Helpers, International Brotherhood of Stationary Firemen, International Union of Steam and Operating Engineers, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Brotherhood Railway Carmen of America, International Association of Machinists, United Association of Plumbers and Steam Fitters of the United States and Canada, Coopers’ International Union of North America—these being the principal unions involved in the movement. John Fitzpatrick was chosen spokesman.

The committee went to Washington. A meeting was held with President Gompers and Secretary Morrison of the A. F. of L. These two officers, perceiving the vast importance of the packing house movement, advised that the matter be taken up with Secretary of War Baker. This was done and the situation explained to him in detail. He was told that a strike in the packing houses would probably become general and that no one could set its bounds or be responsible for its outcome. Much impressed Mr. Baker took the matter under advisement. Two days later he wired the President’s Mediation Commission, then in Minneapolis, to go to Chicago and seek a settlement of the difficulty.

AN AGREEMENT REACHED

The Commission hurried to Chicago and began negotiations at once. The unions stated their case, emphasizing their demand for a conference with the packers as the only way to a solution. The Commission did not think this vital, and carried on its work by meeting with each side separately. Following this method two agreements were drawn up, one between the Commission and the unions, the other between the Commission and the packers. The unions signed at 3 o’clock on Christmas morning.

The gist of these agreements was that there should be no strikes or lockouts during the period of the war. All differences between the unions and the packers that they could not settle among themselves should be referred to the administrator, or arbitrator, whose decision should be final and binding. John E. Williams, a man favorably known to Organized Labor in many arbitration proceedings, was chosen administrator. The demands of the unions were to go to arbitration immediately. Things looked rosy for a peaceful settlement. But there’s many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip.

Meanwhile, Frank P. Walsh, famous as the chairman of the Industrial Relations Commission, came in by invitation of E. N. Nockels, on behalf of the unions, to aid them as an industrial expert in the coming arbitration. Thenceforth to the end he gave them the advantage of his able services without charge. No one acquainted with Mr. Walsh will be surprised at this splendid attitude.

Immediately the administrator took office, on January 2nd, the unions attempted to get the arbitration started. But without success. The packers blocked them at every turn. First, following their original tactics of refusing to meet with the union committee, they insisted that each side be heard alone, the opposing side to know nothing of the argument till several days later when presented with a transcript—a ridiculous proceeding. Then, in flat contradiction of the agreement, they declared that the eight hour question had been settled with the Mediation Commission and could not be arbitrated. They seized upon the most trivial pretexts for delay. And then, as if to show their scorn for the whole situation, they discharged union men right and left. Added to all this there came a sudden and distressing announcement that the administrator had been obliged to resign because of ill-health.

The cup was full. It was evident that the packers had no intention of living up to their agreement, but were seeking openly to destroy the unions, let the consequences be what they might. The unions accepted the issue. They at once broke off negotiations with the packers and sent the committee away to Washington again to demand that the President take over the packing houses, as the only way to guarantee their operation during the period of the war.

On January 18th the committee met with President Wilson, explained to him the imminent danger of a great strike in the packing houses and asked that he take steps to seize the industry. The President replied that the proposed remedy involved a big issue, that he would take it under advisement, and that in the meantime another, effort would be made to get a settlement through arbitration.

Accordingly the packers were called to Washington, and later, under the chairmanship of the Secretary of Labor, brought into a joint meeting with the representatives of the unions. But the ice was not yet broken. The packers still held aloof, ignoring the union men and addressing themselves solely to the chair. Soon tiring of this nonsense, John Fitzpatrick, true to his reputation, stepped across the room, grabbed J. Ogden Armour by the hand and introduced himself. Then a little humanity crept into the meeting, and soon the various representatives of Capital and Labor in the packing industry, after their long period of open war, were making a shape at patching up their differences.

The upshot of the meeting was that Frank P. Walsh and John Fitzpatrick, representing the unions, and Carl Meyer and J. G. Condon, representing the packers, were instructed to get together and agree on as many as possible of the eighteen demands of the workers. The result was that twelve of the demands, relating to the handling of grievances and other shop regulations, were, with minor changes, agreed upon. The other six, relating to wages and hours, were to go to arbitration at once. Whatever increases in wages were allowed by the arbitrator were to be effective as of January 14th. Later on the independent packers also accepted this agreement. The articles agreed to were framed and posted in all the packing houses of the country.

THE ARBITRATION OPENS

The selection of the new administrator was fraught with difficulty. The names submitted by the men were rejected in toto by the packers, and vice versa. Agreement was out of the question on this point. Finally the Secretary of Labor, adhering to the terms of the original agreement of the President’s Mediation Commission, and after securing the approval of the National Council of Defense, appointed Federal Judge Samuel Alschuler to take the place of Mr. Williams, resigned. Upon this man came to rest the full responsibility of establishing the standard of living of the 500,000 people dependent upon the packing industry. Truly a heavy responsibility.

Promptly on time, according to the agreement, Judge Alschuler opened his court of arbitration on February 11th, in the Federal Building, Chicago. Throughout the proceedings, which were public, throngs crowded the court room.

The outstanding feature of the hearing was the exposure of the workers’ overwhelming, crushing poverty. It was as if the characters in “The Jungle,” quickened into life, had come to tell their story from the witness chair. So harrowing and shameful were the tales of misery and despair brought forth that even the tory Chicago Tribune strongly condemned the packers for “social incompetency” and declared that any industry which does not give its workers a living wage should cease to exist.

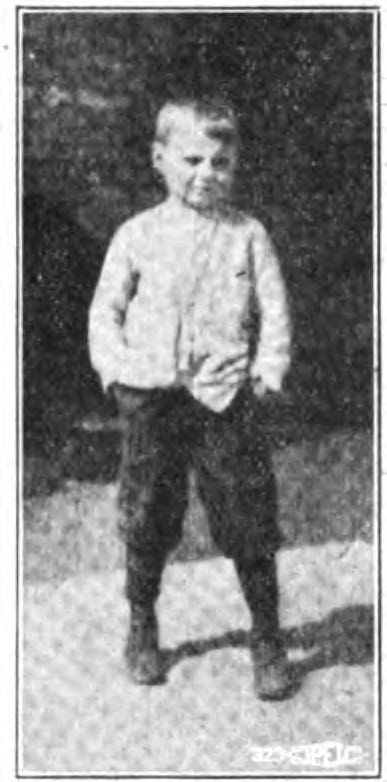

In broken English, or through interpreters, the worker witnesses told the “short and simple annals” of their bleak and barren lives. Educational institutions, public parks, theatres, were nothing to them. Many confessed that they had never even visited a moving picture show. They counted themselves fortunate if, at the cost of hard work and bitter struggle, they could secure enough of the barest necessities to keep body and soul together. One woman, a widow, told a typical story of how her husband, a rugged Pole, came to this country a few years ago, went into the packing houses, fell sick with tuberculosis, continued to work ten to fourteen hours daily to support his family, till finally, “when he had no more blood left” the packers sent him home to die, leaving her and her brood of children poverty-stricken.

Another woman, telling a similar of exploitation and suffering, was, like many others, hatless. Asked why, she replied that several years before, when she came over from Poland, she had had a hat, but it had worn out and she had never been able to buy another, contenting herself with a miserable head-shawl. Asked if she would like to have a hat, she said that what she wanted was food for herself and her children. But supposing she had plenty of food, then would she want a hat? The idea was incomprehensible to her; she wanted food. She couldn’t conceive of a condition in which she and her little ones would have enough to eat. She couldn’t get past the food question. That was the be-all of life to her. A hat—that was beyond her dreams of extravagance. To such depths have the packers, in their unbridled greed, reduced their workers.

Thus it went for days, witness after witness telling the most shocking stories of overwork, underpay, disease, poverty and suffering. The whole city was startled and shamed at the recital. And finally, to impress still more strongly upon the administrator the deplorable working and living conditions of the packing house workers, the unionists proposed that he make a trip through the great plants and the slums “back of the Yards” in order to see things for himself. The trip was made and consumed two days. More than once the administrator was horrified and sickened by the conditions disclosed.

LABOR NOT A COMMODITY

Confronted with damning evidence that the workers were literally starving while the companies were rolling in wealth, the packers, through their attorneys, boldly attempted to escape the responsibility. Why make a horrible example of the packing industry, asked they? It is little, if any, worse than many others. Granted that “back of the Yards” there are fifteen charitable institutions running full blast, and that the district is rampant with every disease and weakness of slum life. What of that? Things are no better in the Ghetto and the steel districts. If the employers of the dwellers in these sections can get away with it, why pick on us?

To bolster up their contention that the Stock yards workers’ poverty results from excessive drinking the packers submitted a map showing over 300 saloons in the comparatively small district, “back of the Yards.” But it proved a boomerang; the workers turned it against them. They demonstrated the close connection between hard, ill-paid work and heavy drinking. Samuel Gompers stated that there are two great classes of intemperates, those who work too much and those who work too little. The heaviest drinkers are those who work the hardest for the least money, and those wealthy idlers who do no work at all. The intemperance of Stockyards workers is not the cause of their poverty, but the result of it.

And then, why ascribe poverty to low wages? Authorities are by no means agreed upon that. The prohibitionists say that it is due to drink. The preachers claim it is the result of sin. The Republicans point out the low tariff as the cause. Others blame it upon thriftlessness, sun spots, and what not. But, said the packers, even if poverty should come from low wages, which of course it does not, we would not be at fault. We are business men and we act according to business principles. We buy labor in the open market. And we pay for it almost as much as the Steel Trust, the International Harvester Company and other enlightened and liberal corporations. We use no compulsion. It is none of our business how our workers live. If they accept our wage it shows they must be satisfied. We don’t pry into their lives. We buy labor just as we do any other commodity necessary to our business. And there our responsibility ends.

Against the cold-blooded sophistry that labor is entitled only to what it can get through cutthroat competition, the workers, under the able leadership of Mr. Walsh, turned their heaviest guns. In the language of the Clayton Act, they declared that “Labor is not a commodity or article of commerce,” it is living, breathing humanity, and must be treated as such. They riddled the argument of a fair bargain between great corporations and individual workers, citing as proof the letters being brought to light from day to day before the Federal Trade Commission by Francis J. Heney, wherein, over their signatures, the packers admit buying up a chief of police, misusing government officials, curtailing production, discharging and locking out union men, etc., in order to overawe their workers and to prevent the consummation of that fair bargaining they now prate about so loudly. The unionists flatly demanded a living wage for packing house workers, regardless of the so-called laws of competition and the rates paid generally in other enslaved industries.

DAMAGING ADMISSIONS BY PACKERS

Following this line of attack they called the great potentate of the packing business, J. Ogden Armour, to the stand and brought him to admit that his employes were entitled to and should get a living wage, one sufficient to guarantee them wholesome food, sanitary homes, comfortable clothing, an opportunity for education, and the simpler recreations. Nelson Morris, another magnate packer, was also brought to the stand and induced to agree to the same. It is difficult to see how these big capitalists could do anything else, when brought into the bright glare of publicity, than grant the creators of their immense wealth at least enough to live upon and to reproduce their kind.

The workers submitted four yearly cost-of-living budgets. They represent different standards of living for toilers, graduating from the starvation line to comparative comfort. All were based on elaborate and exact studies. They follow: Bare Existence, $1177.95; Minimum Standard, $1288.84; Minimum Health, $1434.64; Minimum Health and Comfort, $1551.30. The first, third and fourth were submitted by the Bureau of Applied Economics, presided over by the noted statistician and economist, W. Jett Lauck, who, together with two associates, testified in the arbitration. The second budget was revised from one used in the Chicago street car men’s controversy three years ago.

The admissions of Messrs. Armour and Morris involved their lawyers in difficulties. They had to accept the issue of a living wage whether they would or not. They were compelled to present some sort of an estimate of what a worker can barely scrape along on. Then occurred a remarkable thing. The United Charities of Chicago, after mysterious conferences with a representative of the Armour welfare department, had an inspiration that they, too, should send a budget to the arbitration. Did the packers’ lawyers go to the organized charities for the deliberate purpose of establishing a pauper standard of living in the packing industry? For their sakes we hope not. However, if they did they got badly burned. They found that the standard of living of Chicago paupers was far above that of packing house workers.

The United Charities budget, based on the amounts they actually allow destitute families in the Stockyards district, together with an item of $108, added by them for things indispensable where the head of the family works, totaled $1106.82 per year. On the other hand the actual wage earned by packing house laborers, and they constitute 70 per cent of the total working force, averages about $800 yearly. In other words organized charity, “cramped and iced,” pays to paupers $300 per year more than the packers pay their laborers for working ten hours a day, 300 days a year in the rich and productive packing industry!

Has American industry ever shown a greater shame? Workers paid less than paupers. The packers’ lawyers shied violently from the United Charities budget. To raise their workers up to the standard set by it would require that their whole wage demand of $1 a day increase be granted. The unionists, on the contrary, made good use of the budget. They held that it constituted the best possible proof of the entire justification of all their wage demands. For who would dare to say workers should not have at least as much as paupers?

THE SHORTER WORKDAY

A big battle raged around the question of the eight hour day. In this measure’ the packers saw typified the victory so earnestly sought by the workers. They bent every effort to defeat it. Although compelled to admit the justice, economy and inevitability of the eight hour day as a general proposition, they exhausted every pretext to prevent its consideration, for very obvious reasons, till after the war.

Their strong argument was that, due to the irregular supply of cattle, sheep and hogs, and the limited capacities of the plants, introduction of the eight hour day could only be brought about after months and years of rebuilding and other preparation. To establish it suddenly now would be disastrous. It would reduce the production of vitally necessary foodstuffs full 20 per cent. This would involve starvation for the boys in the trenches and very possibly the loss of the war.

To establish this contention the brainiest superintendents in the packing business piled complexities upon complications. But their efforts were in vain. The workers met and defeated them at every point. Samuel Gompers and Victor A. Olander made the general argument for the shorter workday, and a masterful one it was. Dennis Lane, John Kennedy, Martin Murphy, Tim McCreash, John Joyce and Joseph Selkirk, all skilled butchers, applied it to the packing houses. These union workers destroyed every technical objection raised by the superintendents, checking them one by one. Once, in the midst of the arbitration, they even went to Kansas City to ascertain the exact capacity of certain departments of the packing plants in that city. They routed the experts, horse, foot and dragoons, and proved beyond all question of doubt the practicability and economy of immediately establishing the eight hour day in the packing industry. At the first hour, seeing they were defeated, the packers urged the administrator in case he saw fit to shorten the workday, to make it apply only to the skilled trades—an insidious attack on the unions that did not pass without thorough exposure.

EQUAL PAY FOR MEN AND WOMEN

Much was said of this fundamental measure. As usual, the packers tried to avoid the issue. With much ado they announced their undying fealty to the principle of equal pay for male and female workers. But they denied that there were any men and women doing the same kind of work in their plants. They had “reclassified” the work and made it lighter for the women. That is to say, a women working side by side with a man and doing identical work should be paid from 10 to 15 cents per hour less simply because, from time to time, the man lifts a box from the work bench, or nails a cover on it.

The workers mercilessly exposed this pitiful subterfuge, and showed that in spite of it many women workers are doing exactly the same work as men for much less pay. They asked the administrator, in view of the great complexity of the problem, to establish the principle of equal pay. Later on they would take up the cases in the various departments where the “reclassificaion” scheme is in effect and treat them as grievances.

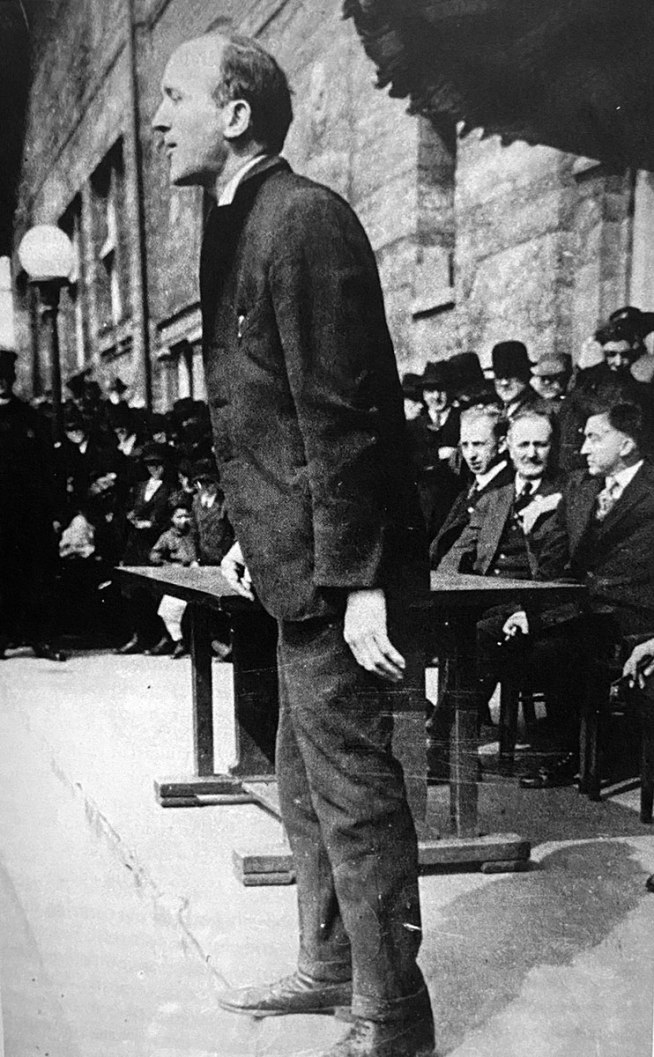

THE AWARD

On March 7th the arbitration concluded. Mr. Walsh made the last argument. In a masterly address lasting six hours he flayed the unfair methods of the packers. With flaming oratory he told the rulers of the packing industry that the day of industrial autocracy has passed and that the day of industrial democracy has arrived. And woe to all tyrants of industry who fail to recognize this fact and to act accordingly. Their doom is at hand.

In a document of 7,000 words Judge Alschuler, on March 30th, brought in his findings on the six questions at issue. They reflect genuine credit upon him as a fair-minded man. In brief, they are as follows:

- The basic eight hour day; to become effective May 5th, 1918.

- Double time for Sundays and six holidays; time and one-fourth for the ninth and tenth hours, and time and one-half for all over ten hours on regular workdays.

- Where three eight hour shifts are worked daily, employes to be allowed 20 minutes off for lunch with pay.

- Wage increases of from 3½ to 4½ cents per hour, the lowest paid workers to get the larger increases. New rates to be effective as of January 14th. When basic eight hour day becomes effective on May 5th employes shall be allowed ten hours pay for eight hours work.

- Equal pay for men and women doing the same class of work.

- A guarantee of five days work per week.

In determining the wage increases and overtime rates the administrator stated he had been influenced by the consideration that, due to war needs, much overtime work was inevitable. Therefore the moderate rates. As it now stands a laborer gets $2.75 for ten hours; under the new rates he will get, for ten hours work, $4.20; that is, $3.20 for the basic eight hour day and $1 for the additional two hours. For Sunday work, and it is plentiful, the laborer will be paid 80 cents per hour instead of 27½, as before.

On Easter, Sunday, March 31st, in a monster open air meeting 40,000 packing house workers assembled and endorsed the award.

CONCLUSION

Between the articles agreed upon by the unions and the packers, and those handed down by the administrator, the foundations of Trade Union principles and practices are firmly established in the packing industry. Strong organizations, the recognized right to organize and to bargain collectively, machinery to handle grievances, the basic eight hour day, extra rates for overtime, Sundays and holidays, one day’s rest in seven, equal pay for men and women, the principle of seniority, 30 day competency clause, guaranteed time—with these weapons in their hands the packing house workers will be well able to fight their way onward to the new freedom.

Great things have been done in the packing industry. An army of oppressed slaves have been put safely on the way to freedom and happiness. And the credit lies with the live spirits of the organizations involved. Never did a group of unionists work more earnestly and faithfully together than they. With hearts and minds set firmly upon the ideal of an organized packing industry, they let nothing stand in the way of its achievement. Progress, determination, energy, sincerity and loyal cooperation were their watchwords. Craft bickerings, personal jealousies, time-honored precedents and revered but outworn tactics they threw to the four winds. They obliterated the very thought of failure and tolerated only those factors making for success. And the natural result is now patent to all—one of the greatest victories ever won by Organized Labor.

What has been done in the packing industry can be done elsewhere just as readily. If so many large industries are unorganized the Trade Union movement is alone to blame. Too often its tactics are fitted to the nineteenth century rather than to the twentieth. Before anything substantial can be done in the big job of organization confronting us the various unions will have to abandon their suicidal jurisdictional quarrels, give up their antiquated policy of individual dabbling and unite themselves loyally in widespread movements inspired with a burning spirit of labor solidarity. When this is done, then the labor movement will take on a growth and prosperity now hardly conceivable, and tremendous strides will be made towards the long-dreamed-of goal of industrial emancipation.

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’PDF of issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/Life_and_Labor.pdf?id=8JBZAAAAYAAJ&output=pdf&sig=ACfU3U3LmdUSZA8BXUg-ugNdyShuD2Xntg