This essay rescues some of that dangerous, deliberately distorted and disappeared history of southern class struggles before the Civil War. Focusing on the decade before the War, in the first section Biel centrally places the rebellion of the enslaved in that class war, with John Brown’s 1859 raid being the exclamation point on years of increasing conflict. In the second section of this richly sourced and notated article, Biel looks at the animosities and clashes between poor and non-slaveholding whites and the Slavocracy, as well as their participation in a common system. A deserving addition to the literature on the subject, this modest corrective challenges a number of still held myths.

‘Class Conflicts in the South 1850-1860’ by Herbert Biel from The Communist. Vol. 18. Nos. 2 & 3. February & March, 1939.

I. SLAVE VERSUS SLAVEHOLDER

The great attention given to the spectacular political struggles between the North and the South in the decade before the Civil War has tended to befog the equally important contests which went on during the same period within the South itself.

Writers have dealt at considerable length with the national scene, have demonstrated a growing conflict between an agrarian, slave-labor society and an increasingly industrial, free-labor society as to which should direct public opinion, enact and administer the laws, appropriate the West—in short, which should control the state. In 1860 the grip of the slave civilization upon the national government was very considerably loosened and clearly seemed destined to complete annihilation. The slavocracy therefore turned to bullets.

But there was more to it than that. The facts are that not only did the slavocrats see their external, or national, power seriously menaced by the Republican triumph of 1860, but they also observed their internal, local power greatly threatened by increasing restlessness among the exploited classes—the non-slaveholding whites and the slaves.

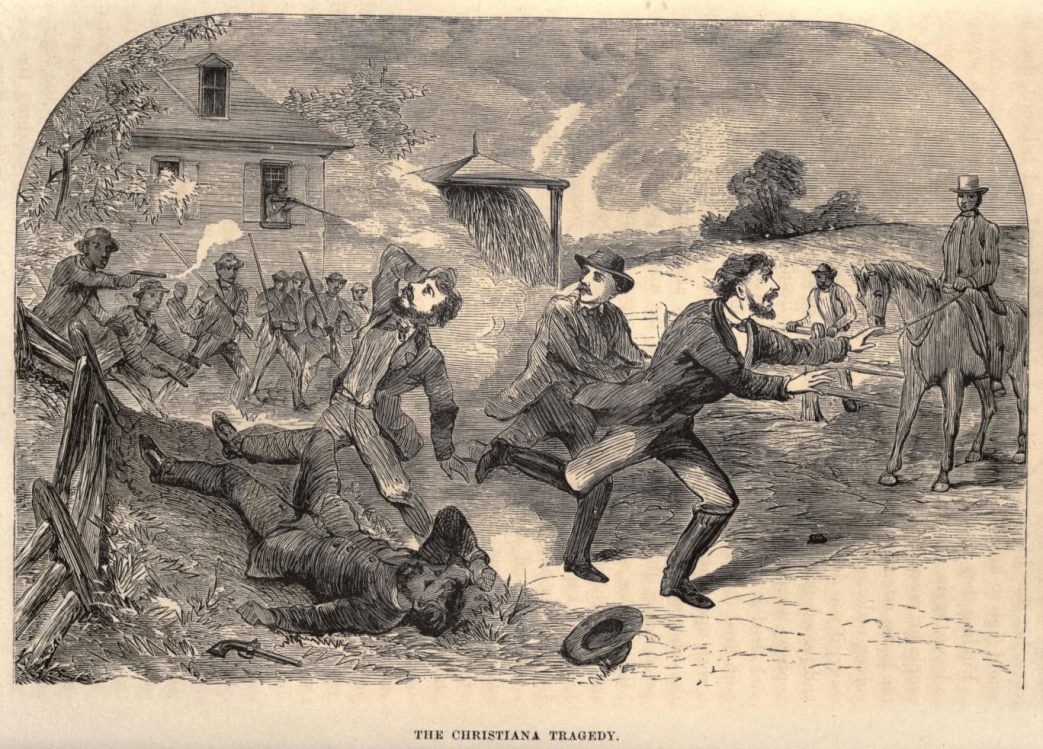

There were three general manifestations of this unrest: (1) slave disaffection, shown in individual acts of “insolence” or terrorism, and in concerted, planned efforts for liberation; (2) numerous instances of poor white implication in the slave conspiracies and revolts, showing a declining efficiency in the divide-and-rule policy of the Bourbons; (3) independent political action of the non-slaveholding whites aimed at the destruction of the slavocracy’s control of the state governments. In the opinion of the writer this growing internal disaffection is a prime explanation for the desperation of the slaveholding class which drove it to the expedient of civil war.

WHY THE UNREST?

Factors tending to explain the slave unrest of the decade are soil exhaustion, leading to greater work demands, improved marketing facilities, having the same result, and economic depression from 1854-56 throughout the South, approaching, especially in 1855, the famine stage. These years witnessed, too, a considerable increase in industrialization and urbanization within the South. These phenomena *1 were distinctly not conductive to the creation of happy slaves. As a slaveholder remarked, *2 “The cities is no place for n***s. They get strange notions into their heads, and grow discontented. They ought, every one of them, to be sent back to the plantations.” As a matter of fact there was for this reason, during this decade, an attempt to foster a “back-to-the-plantation” movement.

It is also true, as Olmsted observed, *3 that: “Any great event having the slightest bearing upon the question of emancipation is known to produce an unwholesome excitement” among the slaves. The decade is characterized by such events as the 1850 Compromise, the sensation caused by Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the Kansas War, the 1856 election, the Dred Scott decision, Helper’s Impending Crisis, Brown’s raid, the election of 1860. If to this is added the political and social struggles within the South itself (to be described later), it becomes apparent that there were many occasions for “unwholesome excitement.”

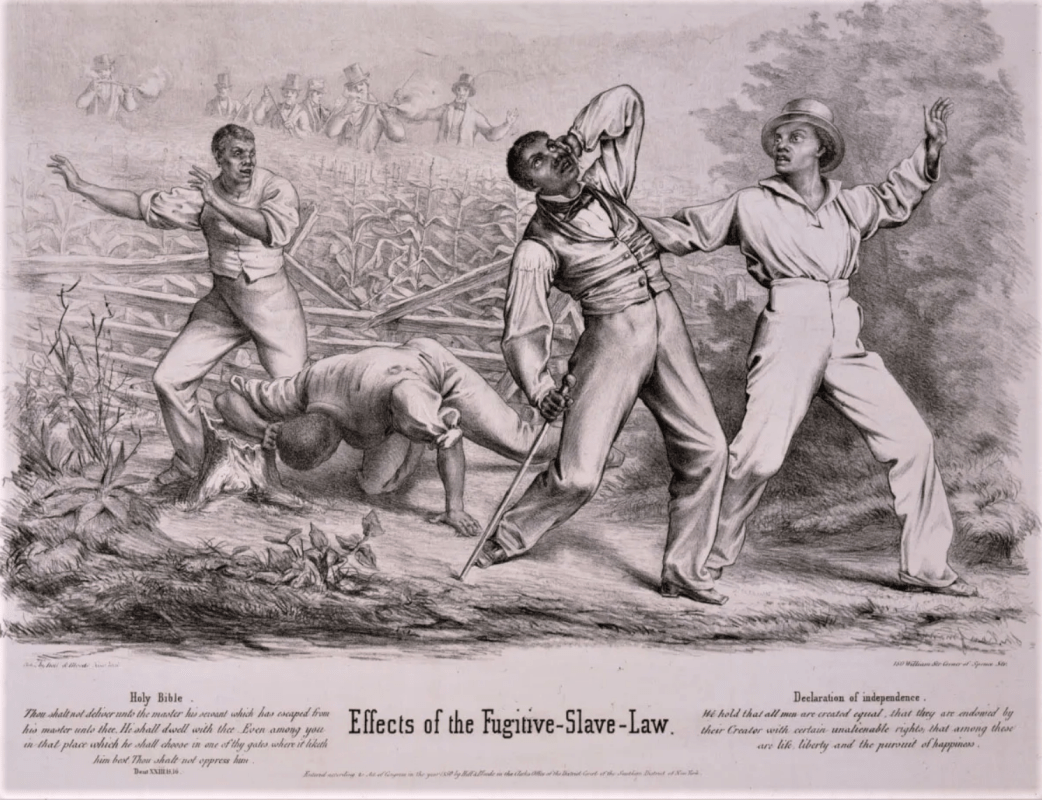

Combined with all this is a significant change in the Abolitionist movement. Originally this aimed at gradual emancipation induced by moral suasion. Then came the demand for immediate liberation, but still only via moral suasion. Then followed a split into those favoring political action and those opposed. Finally, and most noticeably in this decade, there arose a body of direct actionists whose idea was to “carry the war into Africa.”

The shift is exemplified in the person of Henry C. Wright. In the ’forties he wrote the “Non-Resistant’”’ column for Garrison’s Liberator, by 1851 he felt it was the duty of abolitionists to go South and aid the slaves to flee, and by 1859 he was convinced‘ that it was “the right and duty of the slaves to resist their masters, and the right and duty of the North to incite them to resistance, and to aid them.” By November, 1856, Frederick Douglass was certain that the “peaceful annihilation” of slavery was “almost hopeless” and therefore contended *5 “that the slave’s right to revolt is perfect, and only wants the occurrence of favorable circumstances to become a duty…We cannot but shudder as we call to mind the horrors that have marked servile insurrections—we would avert them if we could; but shall the millions for ever submit to robbery, to murder, to ignorance, and every unnamed evil which an irresponsible tyranny can devise, because the overthrow of that tyranny would be productive of horrors? We say not…terrible as it will be, we accept and hope for it.”

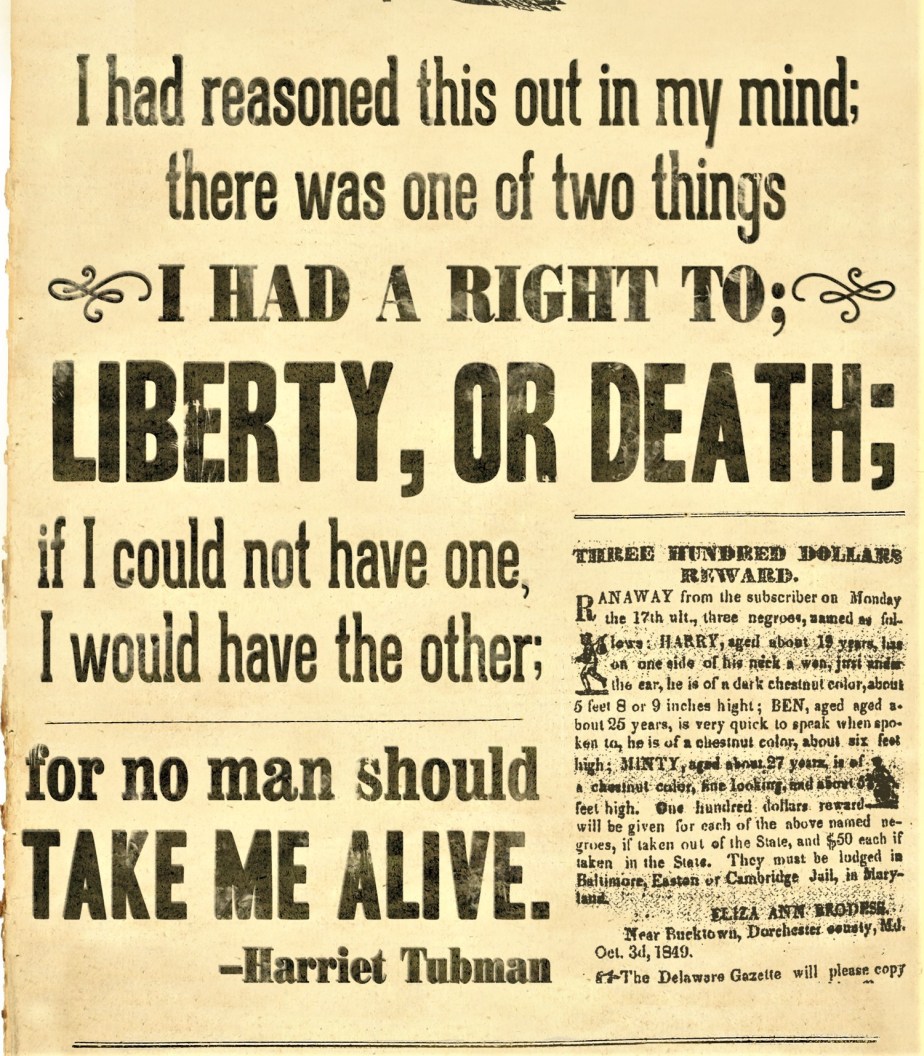

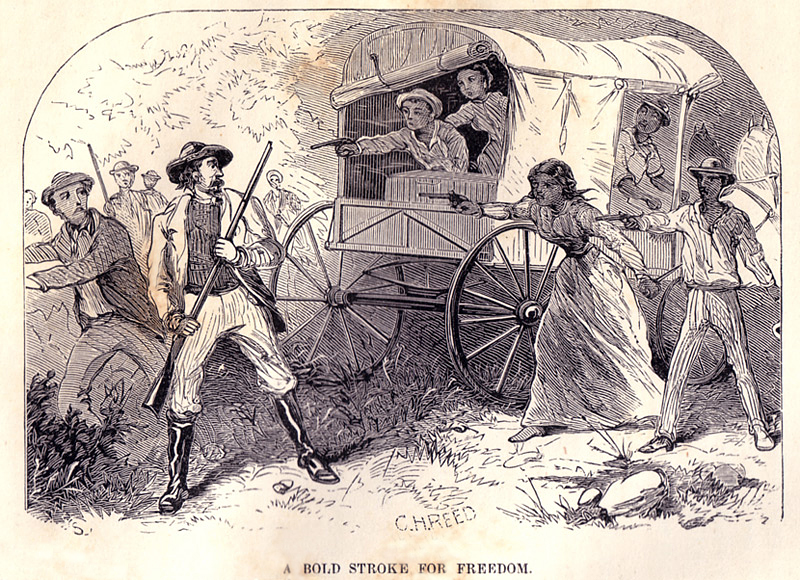

And while John Brown’s work was the most spectacular, he was by no means the only Northern man to agitate among the slaves themselves; there were others, the vast majority unnamed, but some are known, like Alexander Ross, James Redpath, and W.L. Chaplin. *6 But this exceedingly dangerous work was mainly done by Northern or Canadian Negroes who had themselves escaped from slavery. A few of these courageous people are known—Harriet Tubman, Josiah Henson, William Still, Elijah Anderson, John Mason. It has been estimated *7 that, from Canada alone, in 1860, 500 Negroes went into the South to rescue their brothers. What people can offer a more splendid chapter to the record of human fortitude?

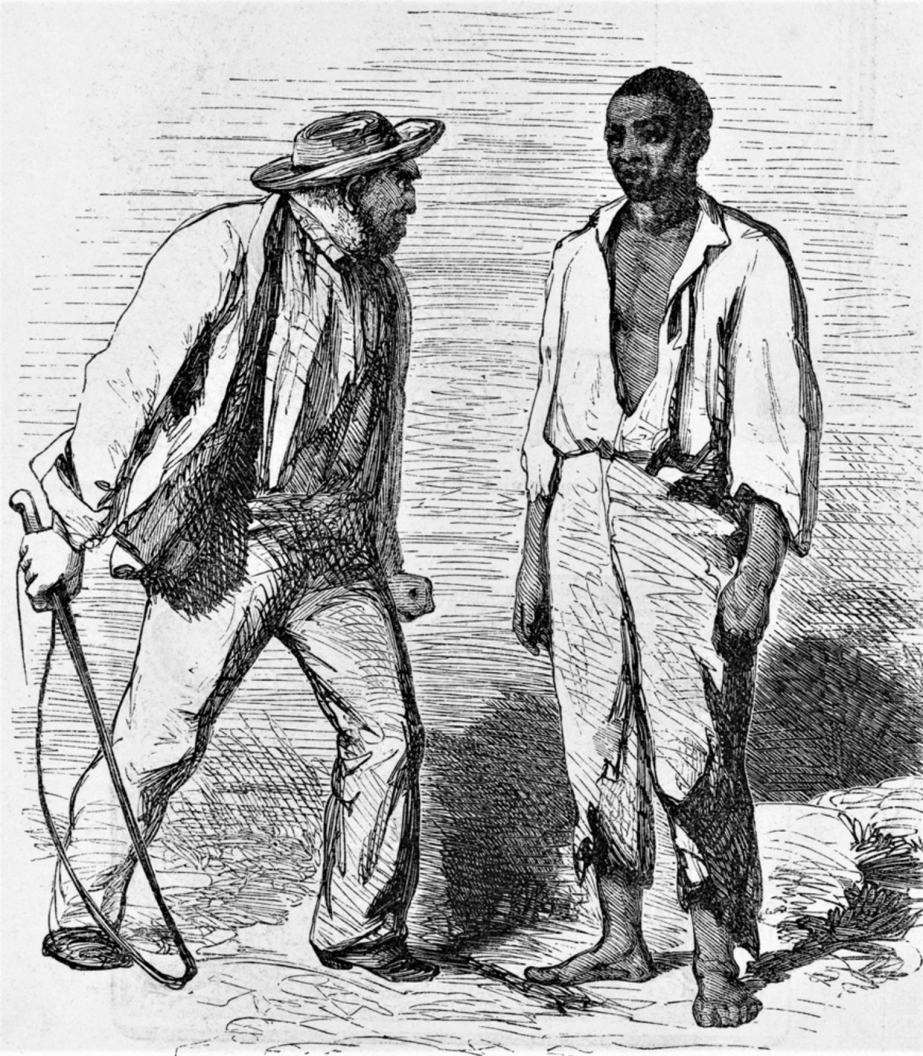

The obvious is at times elusive and it is therefore necessary to bear in mind when trying to discover the causes of slave disaffection that one is indeed dealing with slaves. We will give but one piece of evidence to indicate something of what this meant. In January, 1854, the British consul at Charleston, in a private letter, wrote, *8 “The frightful atrocities of slave holding must be seen to be described…My next-door neighbor, a lawyer of the first distinction, and a member of the Southern Aristocracy, told me himself that he flogged all his own negroes, men and women, when they misbehaved…It is literally no more to kill a slave than to shoot a dog.”

TERRORISM AND INSUBORDINATION

There is considerable evidence pointing to a quite general state of insubordination and disaffection, apart from conspiracies and revolts, among the slave population.

A lady of Burke County, North Carolina, complained in April, 1850, of such a condition among her slaves and declared, “I have not a single servant (slave) at my command.” Three years later a traveler in the South observed “in the newspapers, complaints of growing insolence and insubordination among the negroes.” *9 References to the “common practice with slaves” of harboring runaways recur, as do items of the arrest of slaves caught in the act of learning to read. A paper of 1858 reported the arrest of ninety Negroes for that “crime.” It urged severe punishment and remarked, “Scarcely a week passes, that instruments of writing, prepared by negroes, are not taken from servants (slaves) in the streets, by the police.” *10

A Louisiana paper of 1858 reported “‘more cases of insubordination among the negro population…than ever known before,” and a Missouri paper of 1859 commented upon the “alarmingly frequent” cases of slaves killing their owners. It added that “retribution seems to be dealt out to the perpetrators with dispatch and in the form to which only a people wrought up to the highest degree of indignation and excitement would resort.” *11

Examples of such retribution with their justification are enlightening. Olmsted tells of the burning of a slave near Knoxville, Tenn., for the offense of killing his master and quotes the editor of a “liberal” newspaper as justifying the lynching as a “means of absolute, necessary self defense.” The same community shortly found six legal executions needed for the stability of its society. *12 Similarly, a slave in August, 1854, killed his master in Mt. Meigs, Alabama, and, according to the Vigilance Committee, boasted of his deed. This slave, too, was burned alive. “The gentlemen constituting the meeting were men of prudence, deliberation and intelligence, and acted from an imperative sense of the necessity of an example to check the growing and dangerous insubordination of the slave population.” Precisely the same things happened” *13 in the same region in June, 1856, and January, 1857. Again, in August, 1855, a patrolman in Louisiana killed a slave who did not stop when hailed and this was considered proper *14 since “Recent disorders among the slaves in New Iberia had made it a matter of importance that the laws relative to the police of slaves, should be strictly enforced.”

A common method by which American slaves showed their “docility” was arson. This occurred with striking frequency during the ten years under scrutiny. For example, from Nov. 26, 1850, to Jan. 15, 1851, one New Orleans paper reported slave burnings of at least seven sugar houses. For a similar period, Jan. 31, 1850, to May 30, 1851, there were seven convictions of slaves in Virginia for arson. *15

Burnings were at times concerted. Thus the Norfolk Beacon of Sept. 21, 1852, declared that the slaves of Princess Anne County, Va., had excited alarm and that an extra patrol had been ordered out. And,

“On Sunday night last, this patrol made a descent upon a church where a large number of negroes had congregated for the purpose of holding a meeting, and dispersed them. In a short time, the fodder stacks of one of the party who lived near were discovered on fire. The patrol immediately started for the fire, but before reaching the scene it was discovered that the stacks of other neighbors had shared a like fate, all having no doubt been fired by the negroes for revenge. A strict watch is now kept over them, and most rigid means adopted to make every one know and keep his place.”

The Federal Union of Milledgeville, Ga., of March 20, 1855, told of incendiary fires set by slaves that month in South Carolina and three counties of Georgia. Property damage was considerable and “many persons were seriously injured.” *16

The fleeing of slaves reached very great proportions from 1850 to 1860 and was a constant and considerable source of annoyance to the slavocracy. According to the census estimates 1,011 slaves succeeded in escaping in 1850 and 803 succeeded in 1860. At current prices that represented a loss of about $1,000,000 each year. But that is a very small part of the story. First, the census reports were poor. The census takers were paid a certain sum for each entrant and so tended to make only those calls that were least expensive to themselves. City figures were therefore more reliable than those for rural communities. Moreover, Olmsted found census taking in the South “more than ordinarily unreliable” and told of a census taker there who announced that he would be at a certain tavern at a certain day “for the purpose of receiving from the people of the vicinity—who were requested to call upon him—the information it was his duty to obtain!” *17

According to Professor W. B. Hesseltine, “Between 1830 and 1860 as many as 2,000 slaves a year passed into the land of the free along the routes of the Underground Railroad,” and Professor Siebert has declared *18 that this railroad saw its greatest activity from 1850 to 1860. And this is but a fraction of those who fled but did not succeed in reaching a free land, were captured or forced to turn back. When people pay as high as $300 for one bloodhound *19 the fleeing of slaves is a serious problem indeed.

It is also to be noted that the decade witnessed a qualitative as well as quantitative change in the fugitive slave problem, for now not only did more slaves flee, but more often than before they fled in groups; they, as Southern papers put it, stampeded. *20

Another piece of evidence of the growing unrest of the slave population is afforded by the figures for money appropriated by the state of Virginia for slaves owned by her citizens who were legally executed or banished from the state. *21 For the fiscal year 1851-52 the sum equalled $12,000; for 1852-53 the sum was $15,000; 1853-54, $19,000 was appropriated and the same for 1854-55. For the year 1855-56, $22,000 was necessary and this was duplicated the next year. For 1857-58 the sum was $35,000 and stayed at that same high level for 1858-59. For each of the next two years prior to the Civil War, 1859-60, 1860-61, $30,000 was appropriated. Thus “bad” slaves, legally disposed of, cost the one state of Virginia in ten years the very tidy sum of $239,000.

REBELLION

There was still another manifestation of slave disaffection: conspiracy or revolt. Some of the episodes already described, as that in Virginia in 1852 or in Georgia in 1855, may perhaps be thought of as conspiracies. The decade witnessed many more, the most important of which follow.

A free Negro, George Wright, of New Orleans, was asked by a slave, Albert, in June, 1853, to join in a revolt. *22 He declared his interest and was brought to a white man, a teacher by the name of Dyson, who had come to Louisiana in 1840 from Jamaica. Dyson trusted Wright, declared that one hundred whites had agreed to aid the Negroes in their bid for freedom, and urged Wright to join. Wright did—verbally. He almost immediately betrayed the plot and led the police to the slave Albert. The slave at the time of arrest, June 13, carried a knife, a sword, a revolver, one bag of bullets, one pound of powder, two boxes of percussion caps, and $86. The patrol was ordered out, the city guard strengthened, and twenty slaves and Dyson were instantly arrested.

Albert stated that 2,500 slaves were involved. He named none. In prison he declared that “all his friends had gone down the coast and were fighting like soldiers. If he had shed blood in the cause he would not have minded the arrest.” It was indeed reported that “a large number of negroes have fled from their masters and are now missing,” but no actual fighting was mentioned. Excitement was great along the coast, however, and the arrest of one white man, a cattle driver, occurred at Bonnet Clare. A fisherman, Michael McGill, testified that he had taken Dyson and two slaves carrying what he thought were arms to a swamp from which several Negroes emerged. The Negroes were given the arms and disappeared.

The New Orleans papers tended to minimize the trouble, but did declare that the city contained “malicious and fanatical” whites, “cutthroats in the name of liberty—murderers in the guise of philanthropy” and commended the swift action of the police, while calling for further precautions and restrictions. The last piece of information concerning this is an item telling of an attack by Albert upon the jailer in which he caused “the blood to flow.” The disposition of the rebels is not reported.

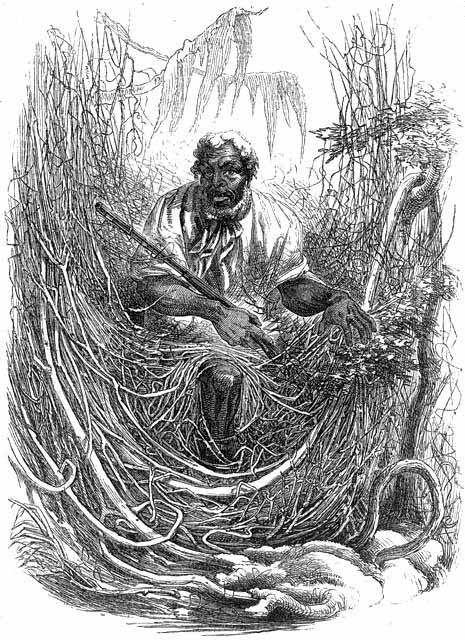

The year 1856 was one of extraordinary slave unrest. The first serious difficulty of the year was caused by maroons in North Carolina. A letter *23 of Aug. 25, 1856, to Governor Thomas Bragg signed by Richard A. Lewis and twenty-one others informed him of a “very secure retreat for runaway negroes” in a large swamp between Bladen and Robeson Counties. There “for many years past, and at this time, there are several runaways of bad and daring character—destructive to all kinds of Stock and dangerous to all persons living by or near said swamp.” Slaveholders attacked these maroons August 1, but accomplished nothing and saw one of their own number killed. “The negroes ran off cursing and swearing and telling them to come on, they were ready for them again.” The Wilmington Journal of August 14 mentioned that these Negroes “had cleared a place for a garden, had cows, etc., in the swamp.” Mr. Lewis and his friends were “unable to offer sufficient inducement for negro hunters to come with their dogs unless aided from other sources.” The Governor suggested that magistrates call for the militia, but whether this was done or not is unknown.

A plot involving over 200 slaves and supposed to mature on Sept. 6,1856, was discovered *24 in Colorado County, Texas, shortly before that date. Many of the Mexican inhabitants of the region were declared to be implicated. And it was felt “that the lower class of the Mexican population are incendiaries in any country where slaves are held.” They were arrested and ordered to leave the county within five days and never to return “under the penalty of death.” A white person by the name of William Mehrmann was similarly dealt with. Arms were discovered in the possession of a few slaves. Every one of the two hundred arrested was severely whipped, two dying under the lash. Three were hanged. One slave leader, Frank, was not captured.

Trouble involving some 300 slaves and a few white men, one of whom was named James Hancock, was reported in October from two counties, Ouchita and Union, in Arkansas, and two parishes, Union and Claiborne, across the border in Louisiana. The outcome here is not known. On November 7 “an extensive scheme of negro insurrection” was discovered in Lavaca, De Witt and Victoria Counties in the Southeastern part of Texas and very near Colorado County, seat of the October conspiracy. A letter from Victoria of November 7 declared that: “The negroes had killed off all the dogs in the neighborhood, and were preparing for a general attack” when betrayal came. Whites were implicated, one being “severely horsewhipped,” and the others driven out of the country. What became of the slaves is not stated. *25

One week later a conspiracy was disclosed in St. Mary parish, Louisiana, It was believed *26 that “favorite family servants” were the leaders. Slaves throughout the parish were arrested. Three white men and one free Negro were also held. The slaves were lashed and returned to their masters, but the four others were imprisoned. The local paper of November 22 declared that the free Negro “and at least one of the white men, will suffer death for the part taken in the matter.”

And in the very beginning of November trouble was reported *27 from Tennessee. A letter of November 2 told of the arrest of thirty slaves, and a white man named Williams, in Fayette County, at the Southwestern tip of the state. It was believed that the plot extended to “the surrounding counties and states.” Confirmation of this soon came. Within two weeks unrest was reported from Montgomery County in the north central part of the state, and across the border in the iron foundries of Louisa, Kentucky. Again many slaves and one white man were arrested. Shortly thereafter plots were discovered in Obion, at Tennessee’s western tip, and in Fulton, Kentucky, as well as in New Madrid and Scott Counties, Missouri.

In December plots were reported, occasionally outbreaks occurred, slaves and whites were arrested, tortured, banished and executed in virtually every slave state. The discontent forced its way through notwithstanding clear evidences of censorship. Thus a Georgia paper confessed *28 that slave disaffection was a “delicate subject to touch” and that it had “refrained from giving our readers any of the accounts of contemplated insurrections.”

The Washington correspondent of the New York Weekly Tribune declared on December 20 that: “The insurrectionary movement in Tennessee obtained more headway than is known to the public—important facts being suppressed in order to check the spread of the contagion and prevent the true condition of affairs from being understood elsewhere.” Next week the same correspondent stated that he had “reliable information” of serious trouble in New Orleans leading to the hanging of twenty slaves, “but the newspapers carefully refrain from any mention of the facts.”

Indeed, the New Orleans Daily Picayune of December 8 had itself admitted that it had “refrained from publishing a great deal which we receive by the mails, going to show that there is a spirit of turbulence abroad in various quarters.” December 3 it said the same thing about “this very delicate subject” but did state that there were plots for rebellion during the Christmas holidays “in Kentucky, Arkansas and Tennessee, as well as in Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas” and that recent events “along the Cumberland river in Kentucky and Tennessee and the more recent affairs in Mississippi, approach very nearly to positive insurrection.”

To this may be added Maryland, Alabama, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. *29 Features of the conspiracies are worth particular notice. Arms were discovered among the slaves in, at least, Tennessee, Kentucky and Texas. Preparations for blowing up bridges were uncovered. Attacks upon iron mills in Kentucky were started but defeated. At least three whites were killed by slaves in that same state. The date for the execution of four slaves in Dover, Tennessee, was pushed ahead for fear of an attempt at rescue, and a body of 150 men was required to break up a group of about the same number of slaves marching to Dover for that very purpose.

Free Negroes were directly implicated as well as slaves in Kentucky, and they were driven out of several cities as Murfreesboro, Tenn., Paducah, Ky., and Montgomery, Ala.

Whites, too, were often implicated. Two were forced to flee from Charles County, Maryland. One, named Tay lor, was hanged in Dover, Tenn., and two others driven out. One was hanged and another whipped in Cadiz, Ky. One was arrested in Obion, Tenn. The Galveston, Texas, News of December 27 reported the frustration of a plot in Houston County and stated, “Arms and ammunition were discovered in several portions of the county, given to them, no doubt, by white men, who are now living among us, and who are constantly inciting our slaves to deeds of violence and bloodshed.”

A letter, passed along by whites as well as slaves, found Dec. 24, 1856, on a slave employed on the Richmond and York Railroad in Virginia is interesting from the standpoint of white cooperation and indicates, too, a desire for something more than bare bodily freedom. The letter reads: *30

“My dear friend: You must certainly remember what I have told you—you must come up to the contract—as we have carried things thus far. Meet at the place where we said, and dont make any disturbance until we meet and d’ont let any white man know any-thing about it, unless he is truth-worthy. The articles are all right and the country is ours certain. Bring all your friends; tell them, that if they want freedom, to come. D’ont let it leak our; if you should get in any difficulty send me word immediately to afford protection. Meet at the crossing and prepare for Sunday night for the neighbourhood—

“P.S. Dont let anybody see this—Freedom—Freeland Your old friend W.B.”

Another interesting feature of the plots of November and December, 1856, is the evidence of the effect of the bitter Presidential contest of that year between the Republican, Frémont, and the Democrat, Buchanan. The slaves were certain that the Republican Party stood for their liberation and some felt that Colonel Frémont would aid them, forcibly, in their efforts for freedom. ‘Certain slaves are so greatly imbued with this fable that I have seen them smile when they were being whipped, and have heard them say that, ‘Frémont and his men can hear the blows they receive.’” One unnamed martyr, a slave iron worker in Tennessee, “said that he knew all about the plot, but would die before he would tell. He therefore received 750 lashes, from which he died.” *31

Of the John Brown raid nothing may be said that has not already been told, except that to draw the lesson from the attempt’s failure that the slaves were docile, as has so often been done, is absurd. And it would be absurd even if we did not have a record of the bitter struggle of the Negro people against slavery. This is so for two main reasons: first, Brown’s raid was made in the northwestern part of Virginia, where slavery was of a domestic, household nature and where slaves were relatively few; secondly, Brown gave the slaves absolutely no foreknowledge of his attempt. The slaves had no way of judging Brown’s chances or even his sincerity, and, in that connection, let it be remembered that slave stealing was a common crime in the Old South.

The event aroused tremendous excitement. The immediate result is well described in this paragraph:

“A most terrible panic, in the meantime, seizes not only the village, the vicinity, and all parts of the state, but every slave state in the Union…Rumours of insurrections, apprehensions of invasions, whether well-founded or ill-founded, alters not the proof of the inherent and incurable weakness and insecurity of society, organized upon a slaveholding basis.” *32

Many of these rumors were undoubtedly false or exaggerated both by terror and by anti-“Black Republican” politicians. Bearing this in mind, however, there yet remains good evidence of real and widespread disaffection among the slaves.

Late in November, 1859, there were several incendiary fires in the neighborhood of Berryville, Virginia. Two slaves, Jerry and Joe, of Col. Francis McCormick were arrested on the charge of conspiracy and convicted. An effort was made to save these slaves from hanging for it was felt that the evidence against them was not conclusive and that since “We of the South, have boasted that our slaves took no part in the raid upon Virginia, and did not sympathize with Brown,” *33 it would look bad to hang two slaves now for the same crime. Others, however, urged their executions as justified on the evidence and necessary as an example, for “there are other negroes who disserve just as much punishment.” The slaves’ sentences were commuted to imprisonment, at hard labor, for life.

In December Negroes in Bolivar, Missouri, revolted and attacked their enslavers with sticks and stones. A few whites were injured and at least one slave was killed. Later, *34

“A mounted company was ranging the woods in search of negroes. The owner of some rebellious slaves was badly wounded, and only saved himself by flight. Several blacks have been severely punished. The greatest excitement prevailed, and every man was armed and prepared for a more serious attack.”

Still later advices declared that “the excitement had somewhat subsided.”

Early in July, 1860, fires swept over and devastated many cities in Northern Texas. Slaves were suspected and arrested. *35 White men were invariably reported as being implicated, and frequent notices of their beatings and executions together with slaves occur. Listing of the counties in which plots were reported, cities burned, and rebels executed will give one an idea of the extensiveness of the trouble and help explain the abject terror it aroused: Anderson, Austin, Dallas, Denton, Ellis, Grimes, Hempstead, Lamar, Milam, Montgomery, Rusk, Tarrant, Walker and Wood. The reign of terror lasted for about eight weeks.

And before it was over reports of disaffection came from other areas. In August a conspiracy among the slaves, again with white accomplices, said to have been inspired by a nearby maroon band, was uncovered and crushed in Talladega County, Ala.*36 About 100 miles south of this, in Pine Level, Montgomery County, of the same state, in that same month, the arrest of a white man, a harness maker, was reported *37 for “holding improper conversations with slaves.” Within five months serious difficulty is reported from that region.

Meanwhile, still in August, plots were uncovered in Whitfield, Cobb, and Floyd Counties in Northwest Georgia. Said the Columbus, Ga., Sun, of Aug. 29: “By a private letter from Upper Georgia, we learnt that an insurrectionary plot has been discovered among the negroes in the vicinity of Dalton and Marietta and great excitement was occasioned by it, and still prevails.” The slaves had intended to burn Dalton, capture a train and crash on into Marietta some seventy miles away. Thirty-six of the slave leaders were imprisoned and the entire area took on a warlike aspect. Again it was felt that “white men instigated the plot,” but, since Negro testimony was not acceptable against a white man, the evidence against them was felt to be insufficient for conviction. Another Georgia paper of the same month, the Augusta Dispatch, admitting: “We dislike to allude to the evidences of the insurrectionary tendency of things…” nevertheless did deign barely to mention the recent discovery of a plot among the slaves of Floyd County, about forty miles northwest of Marietta.

In September a slave girl betrayed a conspiracy in Winston County, Mississippi. Approximately _ thirty-five slaves were arrested and yet again it was discovered that whites were involved. *38 At least one slave was hanged as well as one white man described as a photographer named G. Harrington.

Late in October a plot first formed in July was disclosed among the slaves of Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties, Virginia, and Currituck County, North Carolina.*39 Jack and Denson, slaves of a Mr. David Corprew of Princess Anne, were among the leaders. Other were named Leicester, Daniel, Andrew, Jonas and William. These men planned to start the fight for freedom with their spades and axes and grubbing hoes. And it was understood, according to a slave witness, that “white folks were to come in there to help us,” but in no way could the slaves be influenced to name their white allies. Banishment, that is, sale and transportation out of the state, was the leaders’ punishment.

In November plots were disclosed in Crawford and Habersham Counties, Georgia. *40 In both places whites were involved. In Crawford a white man, described as a Northern tinsmith, was executed, while a white implicated in Habersham was given five hours to leave. How many slaves were involved is not clear. No executions among them were reported. According to the Southern papers the rebels were merely “severely whipped.”

December finds the trouble back again in the heart of Alabama, in Pine Level, Autaugaville, Prattville and Hayneville. A resident of the region declared it involved *41 “many hundred negroes” and that “the instigators of the insurrection were found to be the low-down, or poor, whites of the country.” It was discovered that the plot called for the redistribution of the “land, mules, and money.” Said another source, the Montgomery, Ala., Advertiser of Dec. 13:

“We have found out a deep laid plan among the negroes of our neighborhood, and from what we can find out from our negroes, it is general all over the country…We hear some startling facts. They have gone far enough in the plot to divide our estates, mules, lands, and household furniture.”

The crop of martyrs in this particular plot numbered at least twenty five Negroes and four whites. The names of but two of the whites are known, Rollo and Williamson.

There is evidence *42 of the existence in December, 1860, of a widespread secret organization of slaves in South Carolina, dedicated to the objective of freedom. Said J.R. Gilmore, a visitor in the region:

“…there exists among the blacks a secret and wide-spread organization of a Masonic character, having its grip, password, and oath. It has various grades of leaders, who are competent and earnest men and its ultimate object is FREEDOM.”

Gilmore warned a slave leader, Scipio, that such an organization meant mischief. No, said Scipio, “it meant only RIGHT and JUSTICE.”

The slaves saw the impending war between the states and sang:

“And when dat day am come to pass We’ll all be dar to see! So shut your mouf as close as death, And all you niggas hole your breafh, And do de white folks brown!”

Or, in more sober prose, Scipio told Mr. Gilmore that the South would be defeated “’cause you see dey’ll fight wid only one hand. When dey fight de Norf wid de right hand, dey’ll hey to hold de nigga wid de leff.”” Scipio’s parting words were a plea that Gilmore let the North know that the slaves were panting for freedom and that the poor whites, too, were victims of the same vicious system.

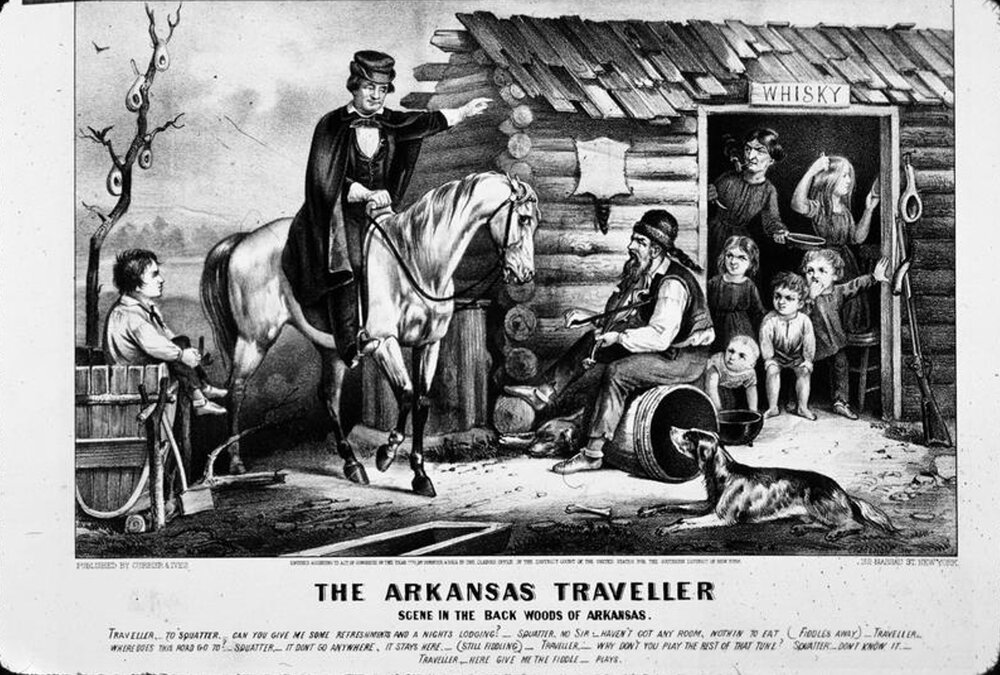

II. NON-SLAVEHOLDER VS. SLAVEHOLDER

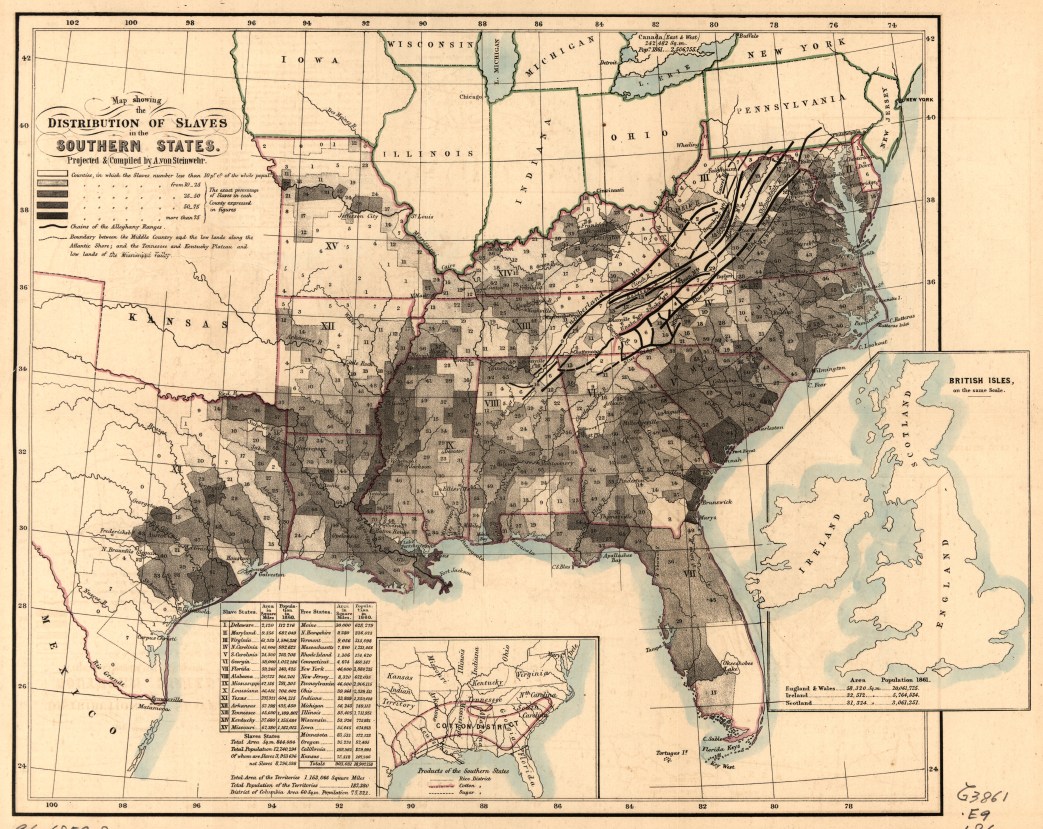

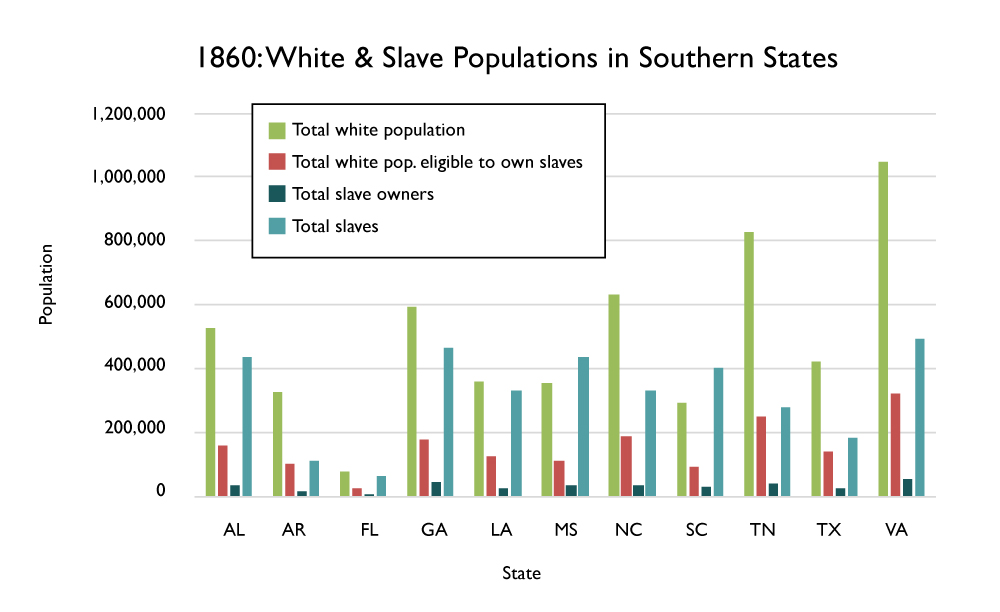

IN 1860 there were over eight million white people in the slaveholding states. Of these but 384,000 were slaveholders among whom were 77,000 owning but one Negro. Less than 200,000 whites throughout the South owned as many as ten slaves—a minimum necessity for a plantation. And it is to be noted that, while, in 7850 one out of every three whites was connected, directly or indirectly, with slave-holding, in 1860 only one out of every four had any direct or indirect connection with slaveholding. Moreover, in certain areas, particularly Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri and Virginia, the proportion of slaves to the total population noticeably fell. *1

These facts are at the root of the maturing class conflict—slaveholder versus non-slaveholder—which was the outstanding internal political factor in the South in the decade prior to Secession. It is, of course, true generally that, “…the real central theme of Southern history seems to have been the maintenance of the planter class in control.” *2 But never did that class face greater danger than in the decade preceding the Civil War.

Let us briefly examine the challenges to Bourbon rule in a few Southern states.

In Virginia, *3 at the insistence of the generally free-labor, non-plantation West united with artisans and mechanics of Eastern cities, a constitutional convention was held in 1850-51. On two great questions the Bourbons lost; representation was considerably equalized by the overwhelming vote of 75,748 to 11,063, and the suffrage was extended to include all free white males above twenty-one years of age. The history of Virginia for the next eight years revolves around an ever-sharpening struggle between the slaveholders and non-slaveholders. The power of the latter was illustrated in the election of Letcher over Goggin in 1859 as Governor. In that campaign slavocratic rule was the issue and the Eastern, slaveholders’ papers appreciated the meaning of Letcher’s victory. Thus, for example, the Richmond Whig of June 7, 1859, declared:

“Letcher owes his election to the tremendous majority he received in the Northwest Free Soil counties, and in these counties to his anti-slavery record.”

In North Carolina, too, there was an “evident tendency of the non-slaveholding West to unite with the non slaveholding classes of the East,” *4 and this unifying tendency brought important victories. In 1850, for the first time in fifteen years, a Democratic candidate, David S. Reid, captured the governorship, and he won because he urged universal manhood suffrage in elections to the state’s senate (ownership of fifty acres of land was then required in order to vote for a senator) as well as to the lower house. Slaveholders’ opposition prevented the enactment of such a law for several years but the people never wearied in their efforts and, finally, free suffrage was ratified, *5 August, 1857, by a vote of 50,007 to 19,379.

A valiant struggle was also carried on for a more equitable tax system— ad valorem taxation—in North Carolina. *6 A few figures will illustrate the situation. Slaves, from the ages of 12 to 50 only, were taxed 534 cents per hundred dollars of their value. But land was taxed 20 cents per hundred dollars, and workers’ tools and implements were taxed one dollar per hundred dollars value. Thus, in 1850, slave property worth $203,000,000 paid but $118,330 tax, while land worth $98,000,000 paid over $190,000 in taxes. A Raleigh worker asked in 1860: “Is it no grievance to tax the wages of the laboring man, and not tax the income of their (sic) employer?”

The leader in the fight for equalized taxation was Moses A. Bledsoe, a state senator from Wake County. In 1858 he united with the recently formed Raleigh Workingmen’s Association to fight this issue through. He was promptly read out of the Democratic Party, but, in 1860, ran as an independent and was elected. The issue split the Democratic Party in North Carolina and seriously threatened the political strength of the slavocracy. Professor W. K. Boyd has remarked, *7 “one cannot but see in the ad valorem campaign the beginning of a revolt against slavery as a political and economic influence….”

Similar struggles occurred in South Carolina. *8 The bitter congressional campaign of October, 1851, in which secessionists were beaten, again by a united front of farmers and urban workers, by a vote of 25,045 to 17,710, was “marked by denunciations hurled by freemen of the back country against the barons of the low country.” The next year a National Democratic Party was launched, led by men like J. L. Orr (later Speaker of the National House), B. F. Perry, and J. J. Evans. *9 Their program cut at the heart of the slavocracy. Let South Carolina abandon its isolationism, let it permit the popular election of the President and Governor (both selected by the state legislature), let it end property qualifications for members of its legislature, let it equalize the vicious system of apportionment (which made the slaveholding East dominant), let it establish colleges in the Western part of the state (as it had in the Eastern), and let it provide ample free schools. And, finally, let it enter upon a program of diversified industry. None of these reforms was carried, except partial advance along educational! lines, but the threat was considerable and unmistakable. *10

SOUTHERN ANTI-SLAVERY SENTIMENT

Overt anti-slavery sentiment was not lacking in the South. One evidence of this has been presented in the material showing that whites were often implicated with slaves in their conspiracies.

The New Orleans Courier of October 25, 1850, devoted an editorial to castigating native anti-slavery men, who, it declared, were numerous. Some even thought that two-thirds of the people of New Orleans would be willing to vote for emancipation. An anonymous letter writer said that this was so because there were so many workers in the city who owned no slaves. Earlier that same year a leading Democratic paper of Mississippi, the Free Trader, had declared that “the evil, the wrong of slavery, is admitted by every enlightened man in the Union.” *11 Professor A. C. Cole has also noted “certain indications which point to a hostility on the part of some of the non-slaveholding Democrats outside of the black belt to the institution of slavery itself.” *12

Competent contemporary witnesses testify to such a feeling, and it certainly was very widespread in Western Kentucky, Eastern Tennessee, Western North Carolina, Western Virginia, and Maryland, Delaware and Missouri. *13

THE IDEOLOGY OF THE SLAVOCRACY

In order to evaluate properly the effect of the misbehavior of the exploited, Negro and white, upon the mind of the slavocracy, it is instructive to investigate its ideology. Formally, the Democratic Party was derived from Jefferson, but by the 1820’s the crux of that democrat’s philosophy, i.e., man’s right and competence to govern himself, was being scrapped in the South, for one of an authoritarian nature; there has always been slavery, there will always be slavery, and there should always be slavery. And, said the slavocrats, our form of slavery is especially delightful for two reasons: first, our slaves are Negroes, and while slavery is good in itself, the fact that we enslave an “inferior” people makes our slavery particularly good; and, secondly, since ours is not a wage slavery, but chattel slavery, we have no class problem.

Thus Bishop Elliot would declare at Savannah, February 23, 1862, that following the American Revolution,

“…we declared war against all authority…The reason of man was exalted to an impious degree and in the face not only of experience, but of the revealed word of God, all men were declared equal, and man was pronounced capable of self-government…Two greater falsehoods could not have been announced, because the one struck at the whole constitution of civil society as it had ever existed, and because the other denied the fall and corruption of man.” *14

And thus, too, a Georgia paper, the Muskogee Herald, of 1856, might exclaim:

“Free society! we sicken at the name. What is it but a conglomeration of greasy mechanics, filthy operatives, small-fisted farmers, and moon-struck theorists?” *15

But here were the mechanics and artisans and farmers, Negro and white, of the South, doggedly agitating and conspiring and dying for the same ‘“‘moon-struck” ideas—liberty and progress! What to do?

There were two ideas as concerns the Negro: reform slavery *16 (legalize marriage, forbid separation of families, allow education); and further repression. The latter, repression, won with hardly a struggle.

The Bourbons were, too, keenly aware of the dangerous trend among the non-slaveholding whites. Propaganda flooded the South to the effect that the interests of slaveholders and non-slaveholders were really the same. Said the press, “…arraying the non-slaveholder against the slaveholder…is all wrong….The fact that one man owns slaves does not in the least injure the man who owns none.” *17

Slavocracy’s leading publicist, J. D. B. DeBow, issued a pamphlet on The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder (Charleston, 1860), and the politicians played the Bourbons’ trump card, the non-slaveholders “may have no pecuniary interest in slavery, but they have a social interest at stake that is worth more to them than all the wealth of the Indies.” *18

But, asked the Bourbons and their apologists, why then does it so often happen that whites aid slaves in their plots? Why, they asked, do some agitate against slavery and distribute “vicious works” like that by North Carolina’s “renegade son,” Helper’s ‘Impending Crisis?’ Why do they struggle for political and economic reforms similar to those of Northern “moonstruck” theorists?

Merchants and capitalists, Northern merchants and capitalists, are sympathetic, they reasoned, “but the mechanics, most of them, are pests to society, dangerous among the slave population, and ever ready to form combinations against the interest of even the slaveholder, against the laws of the country, and against the peace of the Commonwealth. *19 And “slaves are constantly associating with low white people, who are not slave owners. Such people are dangerous to a community, and should be made to leave our city.” *20

A visitor to Georgia, in December, 1859, felt that “the slaveholder seems to watch more carefully to keep the poor white man in subjection than he does to guard the slaves.” *21 The North Carolinian Calvin Wiley warned in 1860:

“…that there was as much danger from the prejudice existing between the rich and poor as between master and slave [and felt that] all attempts . . . to widen the breach between classes of citizens are just as dangerous as efforts to excite slaves to insurrection.” *22

In 1850 a South Carolinian, J. H. Taylor, had written that:

“…the great mass of our poor white population begin to understand that they have rights, and that they, too, are entitled to some of the sympathy which falls upon the suffering…It is this great upheaving of our masses we have to fear, so far as our institutions are concerned.” *23

And in February, 1861, another South Carolinian, observing the growth of a white laboring class and its opposition to the slavocratic philosophy declared:

“It is to be feared that even in this State, the purest in its slave condition, democracy may gain a foothold, and that here also thebcontest for existence may be waged between them.” *24

One month later, March 27, 1861, the Raleigh, N. C., Register observing the increasing class bitterness in its own state actually “expressed a fear of civil war within the state.” *25

What, then, is the situation? The national supremacy of the slavocracy is gone. And its local power is threatened by both its victims—the slaves and the non-slaveholding whites— separately and, with alarming frequency, jointly. The South Carolina Senator James Hammond had warned, in 1847, that slavery’s “only hope” was to keep “the actual slaveholders not only predominant, but paramount within its circles.” *26

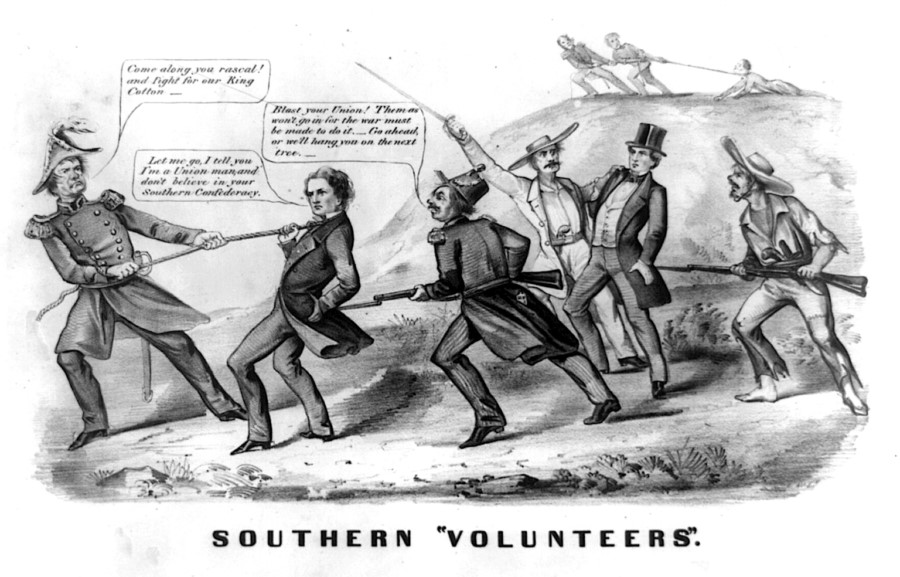

THE SLAVEHOLDERS’ REBELLION

This “only hope” appeared to be slipping away, if it were not already gone, by 1860. Desperation replaced hope, and desperation—the conviction that there was everything to gain and nothing to lose—led to the slaveholders’ rebellion.

And it was their rebellion. As one of them, a South Carolinian, A. P. Aldrich, wrote November 25, 1860:

“I do not believe the common people understand it; but whoever waited for the common people when a great movement was to be made? We must make the move and force them to follow. That is the way of all great revolutions and all great achievements.” *27

One month later a wealthy North Carolinian, Kenneth Rayner, confided to Judge Thomas Ruffin that he “was mortified to find…that the people who did not own slaves were swearing that they would not lift a finger to protect rich men’s negroes. You may depend on it…that this feeling prevails to an extent, you do not imagine.” *28

Just a few days before the start of actual warfare Virginia’s arch-secessionist, Edmund Ruffin, admitted to his diary, April 2, 1861, that it was:

“…communicated privately by members of each delegation (to the Confederate Constitutional Convention) that it was supposed people of every State except S. Ca. was indisposed to the disruption of the Union and that if the question of reconstruction of the former Union was referred to the popular vote, that there was probability of its being approved.” *29

The Raleigh, N. C., Standard, whose editor, W. W. Holden, had been read out of the Democratic Party because of his non-slaveholding proclivities, saw very clearly the result of a rebel. lion whose base was merely several thousand distraught slaveholders. Its editorial of February 5, 1861, warned that:

“The Negroes will know, too, that the war is waged on their account. They will become restless and turbulent…Strong governments will be established and bear heavily on the masses. The masses will at length rise up and destroy everything in their way…”

CONCLUSION

This article has attempted to present a new emphasis upon a factor hitherto insufficiently appreciated in appraising the causes that drove the slaveholding class to desperation and counter-revolution in 1861. This desperation was not merely due to the growing might of a free-labor industrial bourgeoisie, combined, via investments and transportation ties, with the free West, and to that group’s capture of national power in 1860. Another important factor, becoming more and more potent as the slavocracy was being weakened by capitalism in the North, was the sharpening class struggle within the South itself from 1850 to 1860. This struggle manifested itself in serious slave disaffection, in frequent cooperation between poor whites and Negro slaves, and in the rapid maturing of the political consciousness of the non-slaveholding whites.

And, taking another step, he who seeks to understand the reasons for the ultimate collapse of the Confederacy will find them not only in the military might of the North, but, in an essential respect, in the highly unpopular character of that government. The Southern masses opposed the Bourbon regime and it was this opposition, of the poor whites and of the Negro slaves, that contributed largely to its downfall.

REFERENCES Part I.

- G. Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1937, p. 478; J. Redpath,The Roving Editor, N. Y., 1859, p. 127.

- S. C. Abbott, South and North, N.Y., 1860, p. 124.

- F. L. Olmsted, A Journey in the Back Country, London, 1860, pp. 474-75

- The Liberator (Boston) Jan. 10, 1851; H. Wright, The Natick Resolution, Boston, 1859, passim.

- Quoted in W. Chambers, American Slavery and Colour; London, 1857, pp. 154-155-

- A. Ross, Memoirs of a Reformer, Toronto, 1893; J. Redpath, op. cit.; A. Abel & F. Klingberg, A Sidelight on Anglo-American Relations, New York, 1927, p. 258.

- W. H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad, N. Y., 1899, pp. 28, 152.

- Journal of Southern History (1935), 1, Pp. 33; see also R. Ogden, Life and Letters of E. L. Godkin, N. Y., 1907, I, pp. 122, 143; Olmsted, op. cit., pp. 62, 82, 446.

- Johnson, op. cit., p. 496; Olmsted, Journey to the Seaboard Slave States, N. Y., 1904, I, Pp- 32.

- Richmond Daily Dispatch, Sept. 5, 1856, Aug. 24, 1858; J. Stirling, Letters from Slave States, London, 1857, p. 295.

- Liberator, Jan. 29, 1858, citing Franklin Sun, and July 8, 1859, citing St. Louis Democrat. See also Freeman’s Journal (Phila.) Aug. 7, 1852, citing Fredericksburg Herald; Chambers, op. cit., appendix; H. Trexler, Slavery in Missouri, p. 72.

- Olmsted, Back Country, pp. 445-46.

- N.Y. Weekly Tribune, Sept. 16, 1854, Apr. 19, 1856, Feb. 7, 1857, citing Montgomery Journal.

- H. T. Catterall, Judicial Cases Concerning Slavery, Washington, 1932, III, p. 648.

- Louisiana Historical Quarterly (1924), VII, p. 230, citing Daily True Delta; Document No. 46, House of Delegates, 1852, Virginia State Library, Richmond.

- For other examples see Executive Papers for Dec., 1859, and Jan., Nov., Dec., 1860, in archives division, State Library, Richmond; New Orleans Daily Picayune, Nov. 25, 30, Dec. 2, 1856.

- Siebert, op. cit., 26; S. Mitchell, Horatio Seymour, Cambridge, 1938, p. 482; Olmsted, Seaboard, II, p. 150.

- Hesseltine, A History of the South, N. Y., 1936, p. 258; Siebert, op. cit., p. 44.

- Olmsted, Seaboard, I, p. 182.

- Richmond Daily Dispatch, Sept. 17, 1856; Annual Report of American Anti-Slavery Society .. . for year ending May 1, 1859, N. Y. 1860, p. 84.

- Citation in detail for these figures would require too much space. They are taken from the Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia for each of the years mentioned.

- The sources used for this are the New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 14, 15, 16, 23, 1853; The Liberator, June 24, July 1, 8, 1853. citing other Southern newspapers.

- Governor’s Letter Book (MS.), No. 43, PP. 514-15, Historical Commission, Raleigh, N. C.

- Austin State Gazette, Sept. 27, 1856; F. Olmsted, A Journey Through Texas, N. Y., 1860, pp. 503-504, quoting other Texan papers.

- N. Y. Weekly Tribune, Nov. 15, 1856, citing Ouchita, La., Register; Austin State Gazette, Nov. 15, 1856; New Orleans Daily Picayune, Nov. 16, 1856.

- New Orleans Daily Picayune, Nov. 27, Dec. 2, 1856.

- Liberator, Nov. 28, Dec. 12, 1856, citing local papers.

28, Milledgeville Federal Union quoted in U. Phillips, Plantation and Frontier, Ul, p. 116. - Support for this and the following paragraph will be found in Letter Books of the Governors of North Carolina (MS.) T. Bragg, No. 43, pp. 635, 636, 639, 653, 654, located in Raleigh; New Orleans Daily Picayune, Dec. 12, 18, 23, 24, 25, 26, 1856; Richmond Daily Dispatch, Dec. g, 10, 11, 12, 15, 1856; N. Y. Weekly Tribune, Dec. 13, 20, 1856, Jan. 3, 1857; Liberator, Dec. 12, 1856; Ann. Rept. Amer. Anti-Slavery Society 1857-58, pp. 76-77; J. Stirling, op. cit., pp. 51, 59, 91, 294, 297g8; Olmsted, Back Country, pp. 474-75; Journal of Southern History, I, pp. 43-44. An escaped German revolutionist, Adolph Douai, published an Abolitionist paper in San Antonio, Texas, from 1852 until 1855, when he was driven out. See M. Hillquit, History of Socialism in U. S., N. Y., 1910, p. 171.

- Copied by Richard H. Coleman in a letter, asking for arms, dated Caroline county, Dec. 25, 1856, to Governor Henry Wise, in Executive Papers, archives division, State Library, Richmond. Other letters in this source show that the Governor in Dec., 1856. received requests from and sent arms to fif teen counties.

- Letter from Montgomery County, Tenn., originally in The New York Times, in Liberator, Dec. 19, 1856; see also N. Y. Weekly Tribune, Dec. 20, 27, 1856, quoting local papers, and Atlantic Monthly (1858), II, pp. 732-33-

- Principia, N. Y., Dec. 17, 1859.

- Letters quoted are to Governor Letcher from P. Williams, Jan. 5, 1860, and C. C. Larue, Jan. 17, 1860, in Executive Papers, State Library, Richmond.

- Principia, N. Y., Jan. 7, 1860, quoting Missouri Democrat. Karl Marx read reports of this revolt. See his comment and Engels’ reply in The Civil War in the United States, N. Y., 1937, Pp. 221.

- Austin State Gazette, July 14, 28, Aug. 4, 11, 18, 25, 1860; John Townsend, The Doom of Slavery, Charleston, 1860, pp. 34-38.

- Journal of Southern History, 1, p. 47.

- Liberator, Aug. 24, 1860.

- St. Louis Evening News quoted in Liberator, Oct. 26, 1860.

- Material on this is in Executive Papers, Nov., 1860, State Library, Richmond.

- R. B. Flanders, Plantation Slavery in Georgia, Chapel Hill, 1933, p. 275.

- N. Y. Daily Tribune, Jan. 3, May 29, Aug. 5, 1861.

- Edmund Kirke (J. R. Gilmore), Among the Pines, N. Y., 1862, pp. 20, 25. 59, 89, 301

REFERENCES PART II.

- A. C. Cole, The Irrepressible Conflict, New York, 1934, p. 34; L. C. Gray, History of Agriculture in the Southern United States, Washington, 1933, II, p. 656.

- W. Hesseltine, Journal of Negro History, 1936, XXI, p. 14

- See two studies by J. Chandler, Representation in Virginia, Baltimore, 1896, pp. 63-69; History of Suffrage in Virginia, Baltimore, 1901, pp. 49-54; C. H. Ambler, American Historical Review, 1910, XV, pp. 769-76.

- H. M. Wagstaff, State Rights … in North Carolina, Baltimore, 1906, p. 111.

- Memoirs of W. W. Holden, Durham, igil, p. 5; C. C. Norton, The Democratic Party in Ante-Bellum N.C., Chapel Hill, 1930, Pp. 173.

- W. K. Boyd, Trinity College Historical Society Publications, 1905, V, p. 31; Wagstaff, op. cit.; p. 110; Norton, op. cit.; pp. 199-204.

- Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1910, p. 174.

- In 1849 a white man was tried for incendiarism in Spartanburg, S.C., and one of the pieces of evidence against him was a pamphlet by “Brutus” called An Address to South Carolinians urging poor whites to demand more political power. See H. Henry, Police Control of the Slaves in South Carolina, Emory, 1914, p. 159; D. D. Wallace, History of South Carolina, New York, 1934, III, p. 130.

- Laura A. White in South Atlantic Quarterly, 1929, XXVIII, pp. 370-89; White, Robert B. Rhett, New York, 1931, p. 123 and Chapter VIII; Wallace, op. cit., HI, pp. 129-38.

10.For accounts of similar contests elsewhere see, T. Abernethy, From Frontier to Plantation in Tennessee, Chapel Hill, 1932, p. 216; C. Ramsdell in Studies in Southern History and Politics, New York, 1914, p. 66; W. E. Smith, The F. P. Blair Family in Politics, New York, 1933, I, pp. 292, 300, 303, 337, 374, 400, 416, 440.

11.J. B. Ranck, Albert G. Brown, York, 1937, p. 65. - Cole, The Whig Party in the South, Washington, 1913, p. 72; it is true that an anti-Negro feeling was often mixed with the anti-slavocratic feeling of the poor whites. Nevertheless, the latter feeling was present. For example, Hinton R. Helper was anathema to the slavocracy notwithstanding the fact that he was possessed of a vicious antiNegro prejudice.

- Olmsted, Back Country, p. 180; Stirling, Letters, p. 326; J. Aughey, The Iron Furnace, Philadelphia, 1863, pp. 39, 228; see G. G. Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina, p. 577

- W. S. Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in Old South, Chapel Hill, 1935, p. 240.

- Following title page of A. Cole’s Irrepressible Conflict.

- See Liberator, February 1, 1856; R. Taylor. North Carolina’ Historical Review, 1925, II, p. 33:-

- Charlotte, June 12, 1860.

- Senator A. G. Brown of Mississippi quoted by Ranck, op cit., p. 147; see also W. Bean in North Carolina Historical Review, 1935, XIII, p. 115.

- Olmsted, Seaboard, Il, pp. 149-50, quoting a South Carolina paper.

- Mobile, Mercury, quoted in New York Daily Tribune, January 8, 1861.

- J. S. Abbott, South and North, New York, 1860, p. 150.

- G. G. Johnson, op. cit., p. 78.

- DeBow’s Review, January, 1850, quoted by P. Tower, Slavery Unmasked, Rochester, 1856, p. 348, emphasis in original.

- Charleston, Mercury, February 13, 1861, in Political Science Quarterly, 1907, XXII, p. 428; see D. Dumond, The Secession Movement, New York, 193!, p. 117.

- H. M. Wagstaff, op. cit., p. 145.

- D. D. Wallace, op. cit., II, p. 130.

- L. A. White, Rhett, p. 177; see also Marx to Engels, July 5, 1861, in their Civil War in U. S., pp. 228-30, where the votes in the secession conventions are analyzed.

28.C. C. Norton, op. cit., p. 204. - White, Rhett, p. 202.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of February issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v18n02-feb-1939-The-Communist-OCR.pdf

PDF of March issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v18n03-mar-1939-The-Communist-OCR.pdf