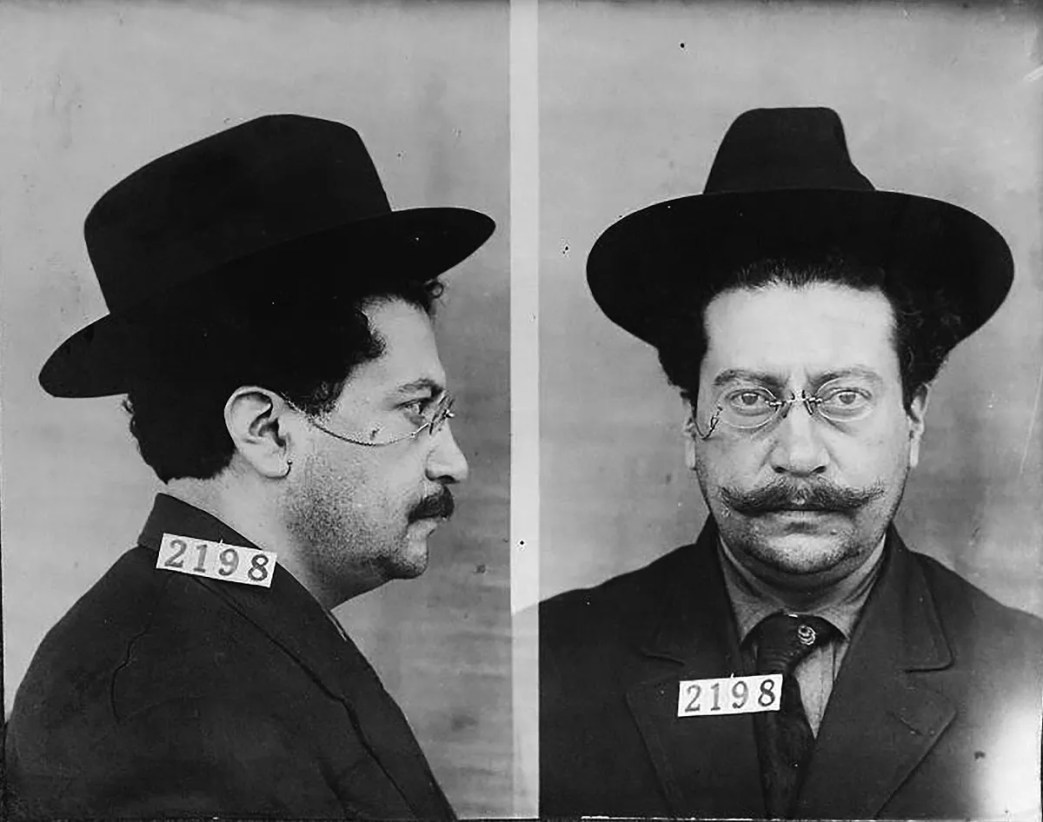

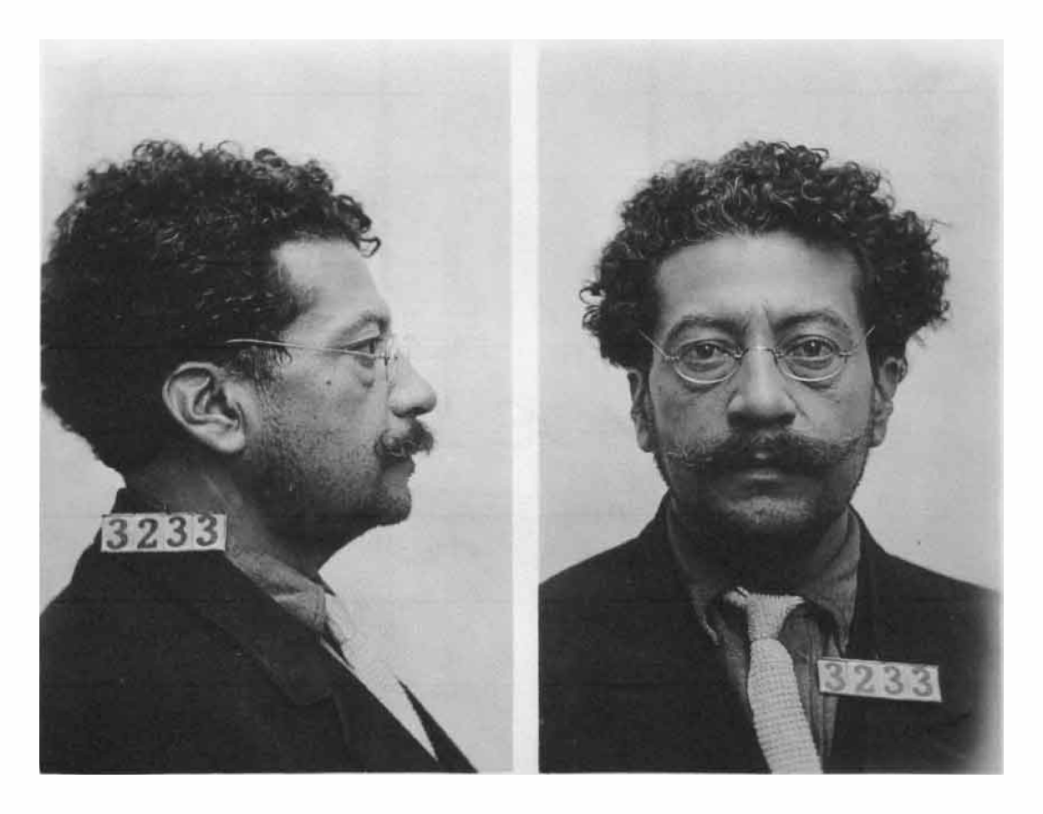

Recently released from five years in Leavenworth the former wobbly activist Harrison George, who joined the Communist movement while inside, remembers learning of the November 21, 1922 death of fellow Leavenworth political prisoner Ricardo Flores Magon and its effects on the inmates. George reflects, from personal experience, on what the capitalist state is capable of doing to its incarcerated enemies and is….not convinced by the official explanation. If Magon was murdered by the U.S. prison regime, he would not have been the first, and certainly not the last. Indeed, it is the expectation.

‘A Small Prison Within A Large Prison’ by Harrison George from The Liberator. Vol. 6 No. 10. October, 1923.

IT was a November dawn. Matuta, goddess of the morning, had painted with tones of rose and gold and pearl; the sky that showed above the high, straight horizon of Leavenworth’s eastern wall.

I had come on prison “sick call” that morning, from the great mess hall where we ate in silence the felon’s ration of corn grist and bitter coffee. I carried the requisite “pass,” signed by my foreman, authorizing me to leave my place of work, go across the prison street to the hospital, receive medical treatment and return.

In the broad, cold belt of the wall’s shadow “sick call” was lining up before the hospital door. Scores of men stood in single file awaiting turn at entrance. Moody faces resigned to pain, faces blotched with disease, faces brutal, faces weak and cowardly, varied the line. Motley, gaunt, and hunched like beasts in the stinging winter wind, they stood shivering beneath their formless cotton garments of prison grey.

A dour-faced guard paced up and down our line, swinging his club. He wore an overcoat. He was authority. Down the street other guards were mustering their gangs four abreast, calling and checking numbers. The air was full of numbers…… Commands, and the gangs slouched off, with clatter of heavy shoes on the brick street.

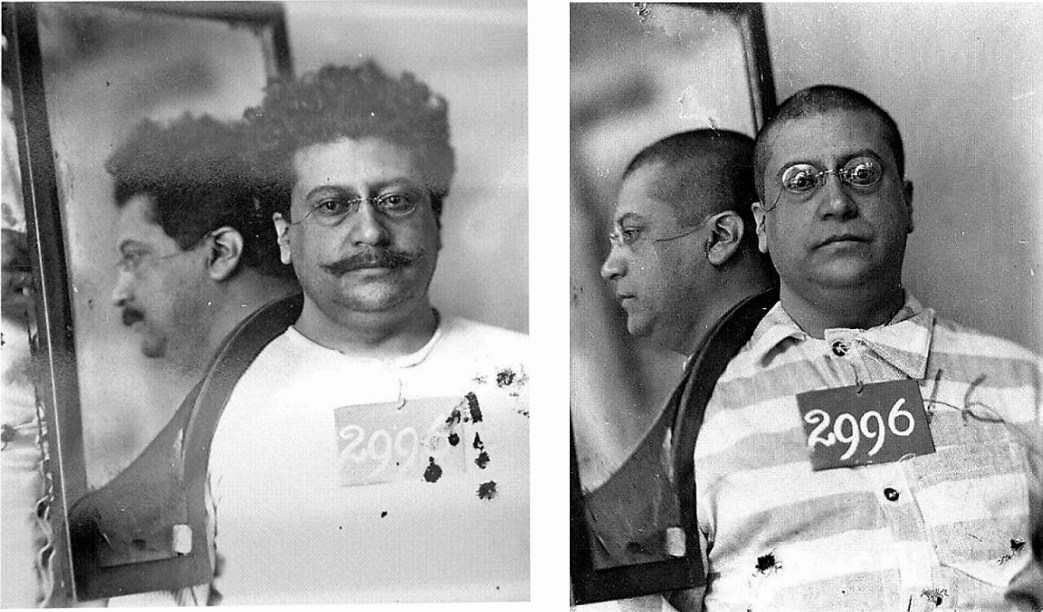

Glancing toward the guard, I stopped for a moment as I passed down the line, beside the figure of a little, old man. Hatless, stooped, and with hands drawn up the sleeves of his jumper, he shook visibly from the cold. His hair was almost white, and in his tense, kind, swarthy face his brown eyes swelled from weeping. It was Librado Rivera.

“Have you heard? Ricardo se murio anoche … ” (Ricardo died last night). He gazed unspoken sorrow.

“Yes. I had heard.” I passed on to the end of the line. Before mess was over I had heard it. Although we ate in strict silence under the eyes of many guards stalking the aisles, from man to man and from line to line the whispered rumor had run that there had died in his cell that night, the great Mexican humanist and revolutionist, Ricardo Flores Magon.

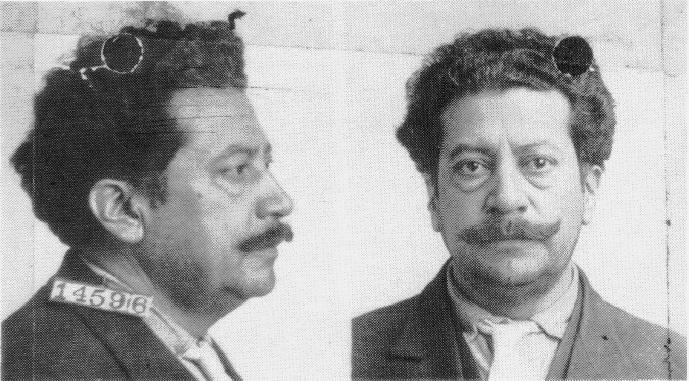

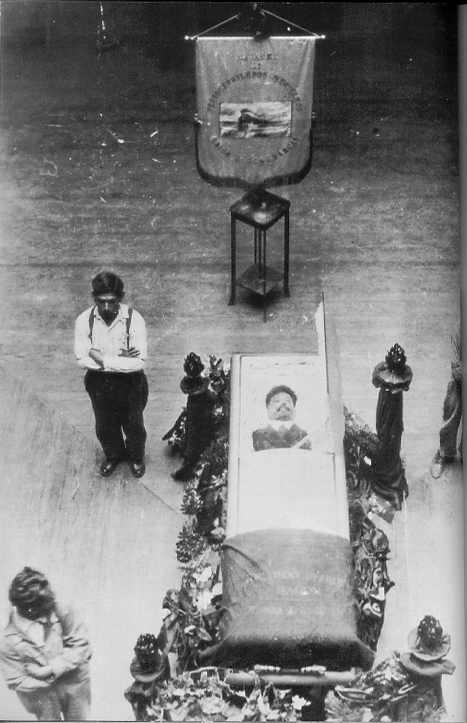

“A small prison within a large prison…that is Leavenworth within the United States,” writes J. De Borran, Mexican, in the preface of “New Life” a book of Magon’s writings published in Mexico. This is the view of the Mexican workers since we sent Magon’s body from a gringo prison to the welcoming arms of the Mexican workers, and since his wife, broken with grief and privation, has been laid beside him; while- north of El Rio Bravo- the workers of the United States are beginning to add up the wrongs they endure to an amazing total.

They look around them- upon a country of espionage, political and industrial; of imperialist wars fought by conscript heroes; of great corporations with private armies of mercenaries; of hangings like those of Frank Little, Wesley Everrest, and Gregor of Arkansas; of strikes broken by federal troops and injunctions; of mass arrests of communists; of jails bulging with prisoners of opinion; of reaction continuing the oppression of the repealed Espionage Act by persecution of workers for “criminal syndicalism;” of outlawed political parties, outlawed labor unions, and outlawed strikes- all compelled to forego activity or live furtively and underground.

As I waited in the sick call line that November morning, the Warden, W.I. Biddle, and the doctor, A.F Yohe, came up and called Librado Rivera- the faithful friend and comrade of Magon through years of privation and prison. The three entered the hospital together. A few minutes later, Rivera, with the sorrow deepened on his face, passed me on his way to work.

“I wrote a telegram to Ricardo’s wife,” he told me in Spanish. “I said that ‘Ricardo died last night of heart disease according to the doctor,’ and the Warden, he made me cut out the words ‘according to the doctor.” His eyes flashed, and I knew that he and every other of the hundreds of Mexicans in Leavenworth- any of whom would have died gladly for Ricardo Magon, firmly believed that Magon had been deliberately poisoned. “Asesinos!” was the word on every Mexican lip.

These Mexicans at Leavenworth, a large percentage totally innocent of crime, yet helpless victims of ambitious border officials, come by carload from El Paso to taste of gringo justice and gringo law at the “small prison within a large prison.” The pathos of the stories they tell! It is enough to cause any American to weep for and curse at his nation, and his race…

WHAT happened to Magon may happen to any fighter for freedom turned over to the mercy of prison doctors and their more ignorant prisoner assistants. Magon was not the first to be mistreated by Doctor Yohe of Leavenworth, who, under an exterior of urbane consideration, coolly allows those radicals that become ill to live or die as best they may. The common dosage for all ills is a few pills, some calomel and a drenching of salts.

Caesar Tabib is in the “TB Ward” today, because in 1919, Doctor Yohe diagnosed him as a malingerer, and Tabib’s tuberculosis became active after months spent on a cement floor in the “hole.” Other cases could be specified, and every political in Leavenworth knows that because I had written up these abuses while out on bond in 1920, I was sent to punishment work on the rock pile when I returned on April 25, 1921, and allowed to suffer for months from a remediable throat infection. This is not my own imagining; I was told the reason of my mistreatment by more than one high official, Pickens, Renoe, Leonard.

Magon, a diabetic and a sufferer from heart disease, whose vision was failing and whose asthmatic cough was constant, could not stand for long the rigors of mistreatment. He died even while the doctor was insisting that he suffered “mildly” or not at all.

EXACTLY what happened to Magon in his dark cell that winter night may never be known. But some things I know from my own experience: Doctor Yohe spends only about three hours a day at the prison. Convict “internes” direct the treatment of the sick at all other hours. Dr. Yohe’s order is that if prisoner falls sick during the night the sufferer is not to be brought from the cell to the hospital unless he has one hundred degrees of fever. The convict “interne” who visits the cell of the sick man, if the man complains of pain yet shows less than the one hundred degrees, gives the sufferer aspirin and, often, sends some bromide from the dispensary to induce sleep. Magon was afflicted with heart disease and should not have taken aspirin.

From authentic sources I learned that Magon called for the “interne” about nine o’clock at night, but received no attention. Again, about the time the cell-house guards change at midnight he put in another call. The “interne” answered this call, and said that he left Magon, who complained of pain (but evidently had no high fever), to send some medicine from the dispensary. The “runner” who took the medicine from the dispensary to the cell-house, says it was a bromide-a heart depressant. When the bromide reached Magon he was already dead. There is no way of eliciting from the poor wretch of an “interne” if he did or did not give Magon, suffering from a cardiac attack and needing a stimulant, the depressant aspirin before he sent the milder depressant bromide.

Upon the reports of Doctor A.F. Yohe, that Magon was in no danger of dying, the Department of Justice acted in refusing the appeals for his release, even by the Mexican government. But neither the blame nor the danger ends there. Those who approve of the Espionage Act must approve of this, its consequence. Those who do not do their utmost to wipe out the dishonor of keeping war time prisoners in Leavenworth, must prepare to learn of other deaths behind its walls.

WHAT of the “large prison” that is the United States? The large prison of my country into which I emerged after serving out my five year sentence upon a charge so nebulous that it is legally referred to as “a state of mind!”

San Quentin holds eighty-seven I.W.W.’s, whose only crime is membership in that organization. More are going in all the time. A sympathetic lady who went from Chicago to aid in their defense has an injunction brought against her by the State of California ordering her to desist in her sympathies. All are charged with “criminal syndicalism,” which is a term that has come to mean anything with which prosecutors can frighten jurors. Thirty communists face trial in Michigan on the remarkable charge of “assembling” contrary to that state’s “criminal syndicalist” law. C.E. Ruthenberg has already been convicted of “assembling!” Are these things, and others, to continue without popular protest?

What of the “rights” of free speech, press and assembly? Go ask those who lie at Leavenworth and the other prisons! Go ask those who murdered Frank Little for the Anaconda Mining Company! Consult the gunmen of the “Copper Queen” who deported twelve hundred miners into the burning desert of New Mexico from Bisbee, Arizona! Ask Fickert and Landis! Ask Daugherty and Burns!

MAGON’S body and that of his life’s mate sleep together in the soil of his beloved Mexico. Now, from Mexico comes the little book of his writings, and in its preface I read “Un presidia pequeno dentro de un presidia grande; eso es Leavenworth y Los Estados Unidos .

It is a rebuke to the United States from the Mexican people: “A small prison within a large prison; that is Leavenworth and the United States.”

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1923/10/v6n10-w66-oct-1923-liberator.pdf