Marxist art critic Charmion von Wiegand contrasts the different paths taken by Pablo Picasso and Giorgio de Chirico.

‘Chirico and Picasso’ by Charmion von Wiegand from New Masses. Vol. 22 No. 3. January 12, 1937.

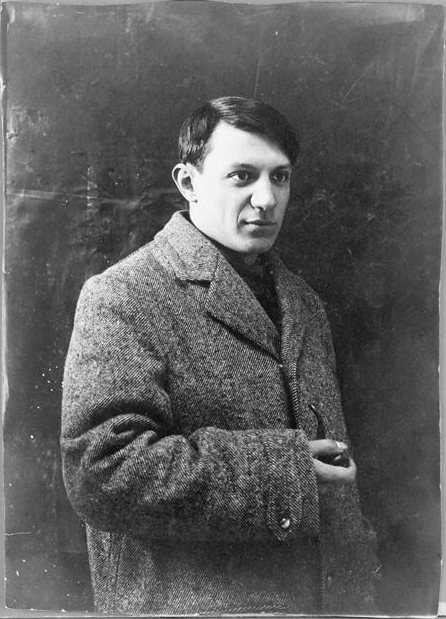

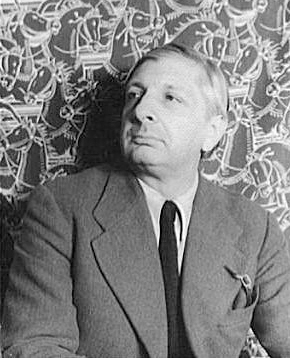

THE ups and downs of capitalism are mirrored not only in stock market quotations but in modern painting. Both finance and art are frantically seeking to solve basic, mortal contradictions in the system in their own terms. Painting transmutes these crises in the economic world into its aesthetic and formal terms, a fact which had perhaps no better exemplification than in the lives and work of Picasso and Chirico, both of whom have recently come under special notice as a consequence of retrospective shows in New York galleries this season. Chirico, born in Greece in i888 of Italian parentage, has been declared both a Surrealist and a pure classic painter. Picasso, born in Spain in 1881, is the leader of French painting.

While Picasso has held public attention almost since the beginning of the century, Chirico became a fashion only in the last five years, a period coinciding with the rise of fascism in Europe. His is an art which appeals directly to the reactionary intelligentsia seeking ideological support for fascism. It is clear that the destructive and uncreative movement, fascism, can develop no unity of thought and that therefore it is forced to plunder its ideas from Marxism, mysticism, and mythology, mixing them in a strange distorted melange of disintegration.

The ups and downs of capitalism are the fundamental reason why a splendid artist like Picasso, instead of creating a single great style in art, has gone through the whole history of western art in the course of twenty years. This see-saw of change is not due to a desire to pleasure a capricious market or to express originality so much as to the deep need of rescuing some synthesis from the ever-increasing confusion of social life. Chirico, in his own way, reflects this intermittent fever of change, but since he is less intuitively aware and less profoundly conscious of the conflict, his work appears more unified than that of Picasso. His range is much smaller. While both painters are necessarily representative of the old class, their direction marks them as moving toward opposite poles.

Chirico has never been a classic artist. His work is an attack on the Greco-Roman heritage of our culture. By nature necromantic and decadent, he deals with the corruption of the classic ideal, expressed in canvases populated with legendary heroes in togas, fallen Ionic columns, shattered pediments, wooden horses, Roman gladiators, marbelized arenas, and gilded laurel wreaths. These gaudy props from a provincial Roman circus hide ideas and feelings directly antipathetic to classic art. In this they are related to the facade of classicism with which fascism masks its naked brutality and intellectual bankruptcy -for instance, its use of Roman fasces in Italy, of standards of Roman legions in Germany. Such historic hocus-pocus is merely a demagogic gesture toward the people. Chirico’s painting mirrors this pseudo-classic masque of anarchy, yet it would be a mistake to confuse him with a real fascist artist. No matter how adulterated his art, he remains in the European tradition, albeit at the end of its road. The official fascist painters, so advertised in the late Venice international exhibition, dwell in no cultural milieu; they merely manufacture debased illustrations of modernism or hand-made chromos of the classics.

In his late work, Chirico has approached one step nearer this fascist disintegration. In his continuous exploration of the limits of corruption, he has descended to the production of chromos, as in several horse pictures a la Delacroix and two mawkish landscapes, “Flying Phantom.” Such taste is akin to the fashionable resurrection of the Victorian whatnot. In an effete society, imitation acquires its own value as genuineness once had, so that one prefers marbelized wall paper to marble, wax flowers to real ones. This is no new phenomenon in history, as witness the late Pompeiian and Roman frescoes.

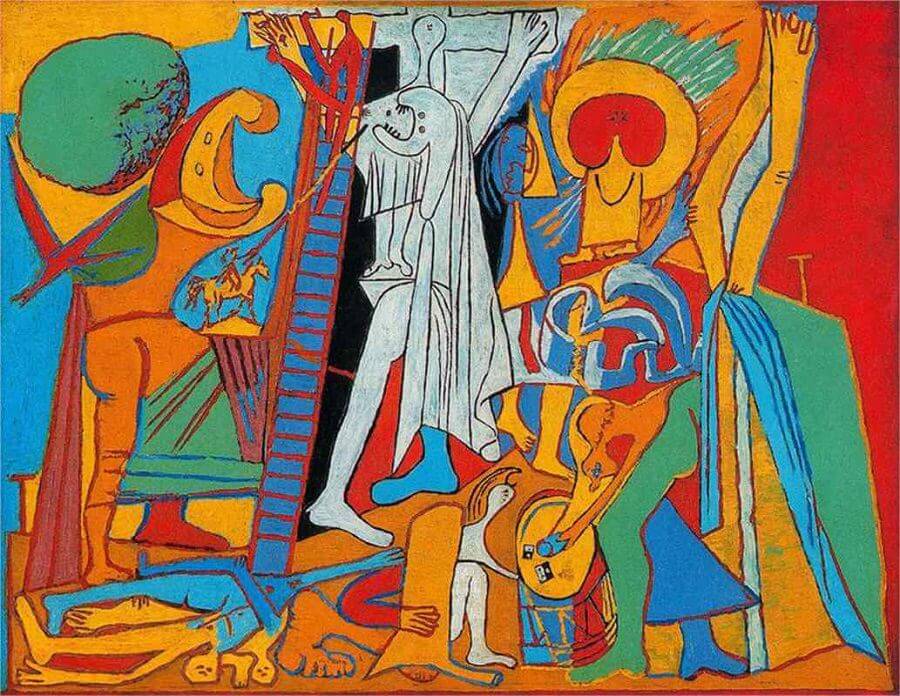

In sharp contrast to Chirico, Picasso, despite some excursions into decadent bypaths (his Alexandrian water colors) has followed in the great line of European tradition, seeking always to analyze form in space without the use of illusionist or illustrative means. Chirico deals with classicist motifs at the moment of their destruction under the impact of Christian ideas, selecting as models the debased, mixed art of the late Roman Empire. Picasso’s work stems directly from the Renaissance -that robust period when the rising bourgeois class affirmed its faith in corporeal reality and set up the classic as its ideal, instinctively sensing the social kinship between the new commercial capitalism and the Greco-Roman world whose power also stemmed from commerce. In such periods of expansion, exploitation, and competition, earthly and individual man, long hidden under the hieratic priest robes, becomes the central theme of art, the aesthetic task, the conquest of anatomy and perspective. As capitalism developed to a higher form, the static aspects of the problem were solved and by Michelangelo’s time, the artist was wrestling with the problem of dynamic movement. In this epoch, painting is seized by an almost cosmic rhythm in which the great bodies extricated from the Palatean calm of marble move like storms through space-Michelangelo, Tintoretto, El Greco.

If Picasso, coming at the very end of this tradition, has found no solution to his problem, this is due chiefly to the class and the historic moment in which he is placed. The flower of his experiments, Cubism, has contributed directly to modern life. Thus he represents on the one hand a great technical advance, but in content he remains behind the simple but moving art of its beginnings—for instance, Giotto. Humanism on which our culture has been based is destroyed by mechanism. Picasso has divested form of all human semblance, dissecting it into dismembered and isolated fragments unrelated to living organic life. Like X-ray portraits where only the structural foundation of an organism is preserved, man and his physical body, the chief Extra-Curricular concern of classic and Renaissance art-is superseded by an impersonal architecture of formal structure.

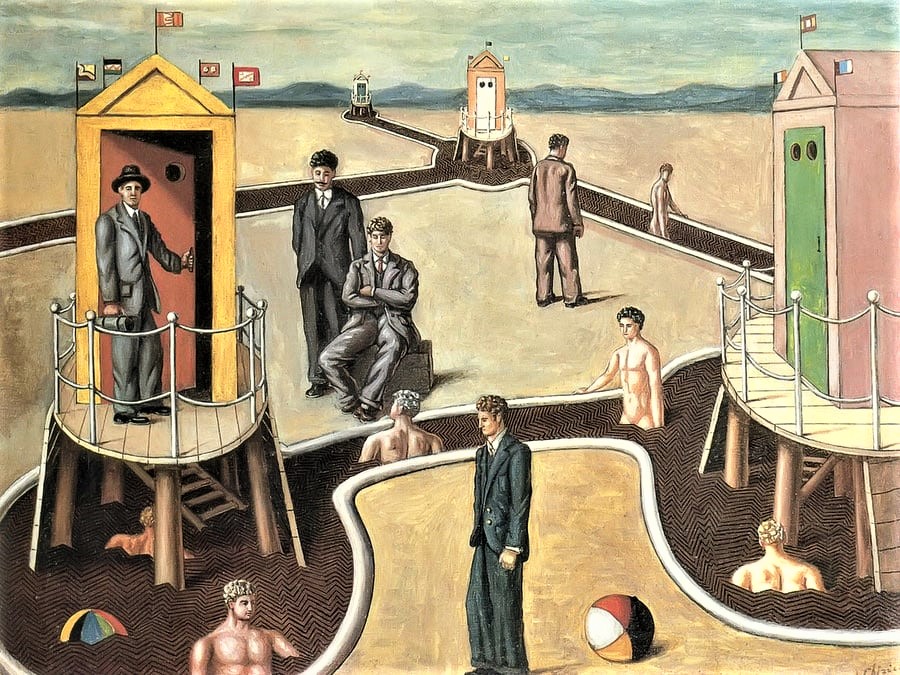

Chirico solved the problem of form by a complete evasion. His early lyric paintings, where the long shadow of late afternoon and of green twilight inundates landscapes of ruined cities sleeping by the wine-dark sea, gave us many charming illustrations. This illustrated elegy on the death of time and space, this romantic yearning for the lost golden age of Greece, is now supplanted by ornament. Movement, expressed in his fantastic horses, is stilled-in the present pictures a horse dies on the seashore; another horse is placed alive in a sarcophagus, and finally two dead horses are displayed in a store window. At the same time, the hushed nacreous grey of twilight is flushed with a brownish golden tone. The deliberate mystifying “Mysterious Bathers” series displays nude youths bathing in a river of geometric herringbone design of endless pattern- their bodies already submerged in the muddy brown net, while over all is poured the somber gold light of the mosaic art. The world of magic sends its shimmering golden light over the world of the dying senses. A new iconoclasm from the east destroys the classic motifs. Chirico’s art has become a graphic ornament in two dimensions—1he too has come to the end of a road.

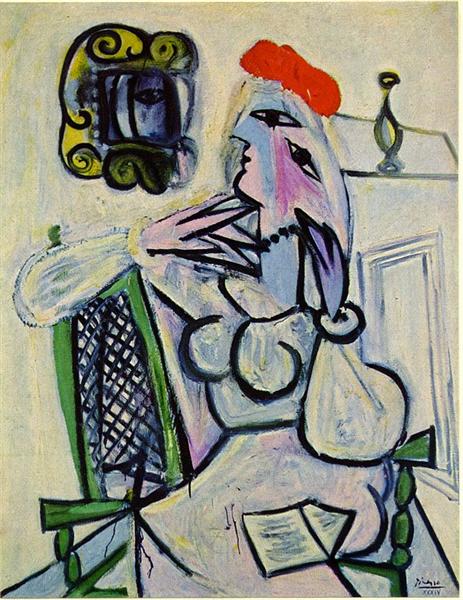

Strangely Picasso in his own late work repudiates form in the sense of volume. Five monumental paintings of 1933-4 display a frankly two-dimensional pattern in which color circulates like a warm bloodstream through rhythmic arabesques. The old themes are used: the woman and her mirror, the Red Hat, the woman holding a book, but there is something new in the monumental patterns akin to Surrealist forms but on a grand scale. Picasso moving in the main line of our cultural development has also come to the end of a road. The ruling class of a dying society is totally unable to offer any new content for a living art. But while Chirico offers us no beginning, one discerns in these paintings of Picasso a possibility of a new art-either mural or moving as in cinema. Following in the tradition of humanism, Picasso has carried it to its logical end-the destruction of man-and now he destroys the abstract form in which he had so skillfully embalmed him. It is left for a new and progressive class to carry on at this point-for only the working class is healthy and strong enough to build a new humanism on a constructive basis and to solve the critical problem of the human relationships in society.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v22n03-jan-12-1937-NM.pdf