‘The War and American Unionism’ by Louis C. Fraina from The Class Struggle. Vol. 1. No. 2. July-August, 1917.

It cannot be too much emphasized that the attitude of American unionism toward the war, and of laborism generally in all the belligerent nations, is a direct consequence of their general program during the days of peace.

The policy of “harmony between labor and capital,” the animating principle of the American Federation of Labor and trades unionism generally, results from the belief that the interests of labor depend upon the interests of capital.

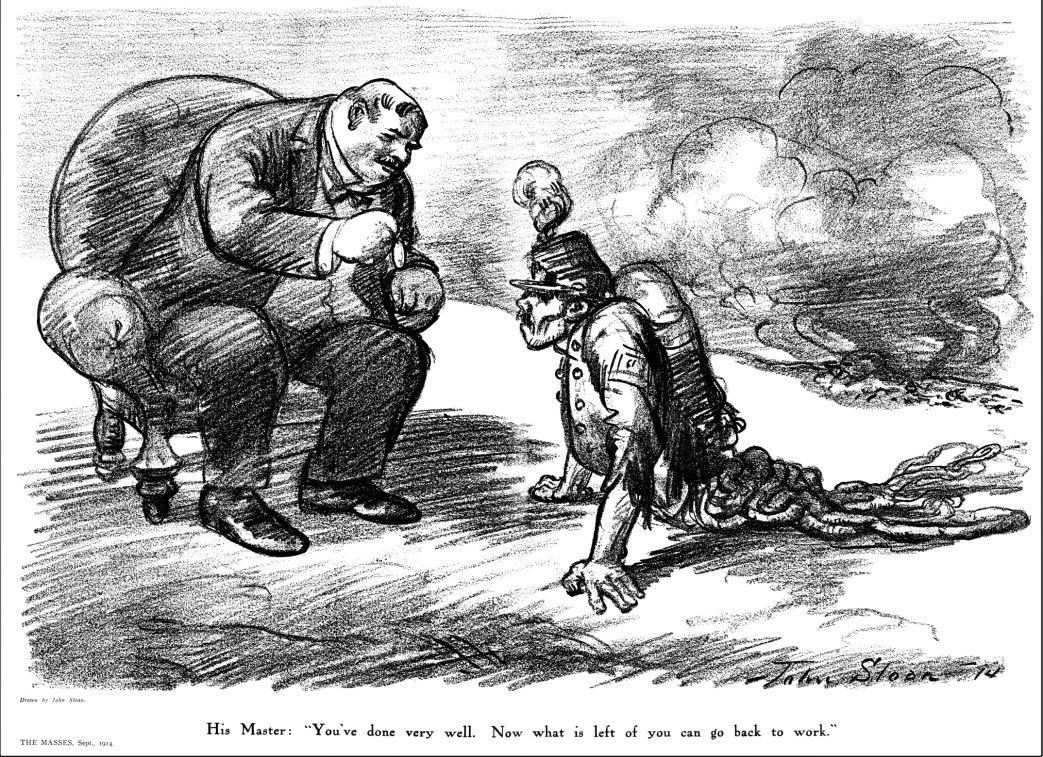

Where these two clash, it is assumed as being purely accidental and incidental; their identity of interests is still the dominant factor. As the struggles between groups in the capitalist class, often severe and bitter, do not destroy their fundamental identity of interests, so the struggle between labor and capital, according to the union theory, does not altar their identity of interests.

Accordingly, the unions are careful that their struggles should in no way menace capitalism itself, or cripple the competitive power of their employers. Often has a union been cajoled into submission by the employer’s plea that its actions were endangering his power to compete successfully with a rival, and that the union was driving him out of business. The employer must be fought, but his power must not be menaced.

On the field of international action, this principle expresses itself in backing up the capitalist class in its projects of expansion and in its wars. If our capitalism is weakened by a defeat, reason the unions, we shall suffer through unemployment, higher hours and lower wages; and, therefore, they fight for the interests of their exploiters in the mistaken belief that they are thereby promoting their own interests. This narrow nationalism is manifest during the days of peace in the A. F. of L.’s stand against immigration, and also in the virtual exclusion of foreign, unskilled workers from membership in the unions.

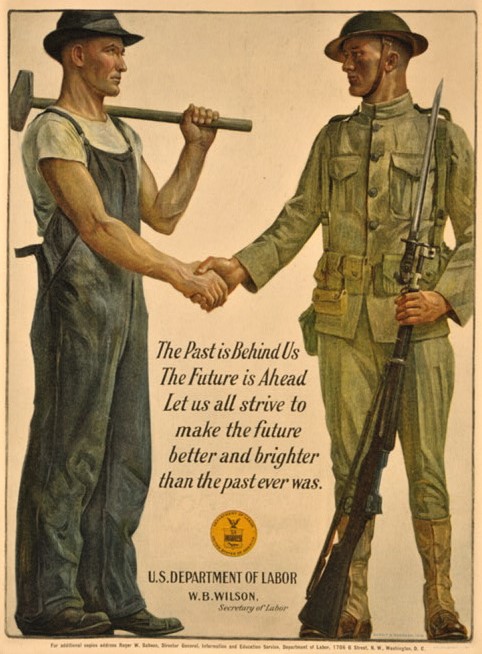

It was therefore inevitable that American unionism should back up the government in the war. The A. F. of L. officially, and various of its affiliated unions, are active in the work of mobilizing our military and industrial forces. Samuel Gompers is an active member of the Council of National Defense; the unions are facilitating the work of recruiting, etc., and many members of the unions are pestiferous members of the Home Guard.

The “civil peace” concluded by the A. F. of L. with the ruling class is a corrollary of the “civil peace” that prevailed before the war. Because of this fact, the government and the union officials expect no strikes and no troubles to impede industrial mobilization. But the masters are uneasy, nevertheless. In spite of the fact that conscription provides the government with power to suppress strikes, the capitalist class is trying to make assurance doubly sure by means of no-strike legislation, plentifully proposed in Congress. The American government has learned from the mistakes of England, and is not contemplating any measures that would provoke labor- that is, measures against those petty privileges of unionism which unionism considers more vital than its fundamental general interests.

Samuel Gompers considered that he was playing a very shrewd game. His assumption was that, having offered the unions’ services to the government, the unions would be in an excellent strategic position to extort concessions. But the government was shrewder. In a Washington dispatch to the New York Evening Post, David Lawrence very aptly summarizes the situation:

“England went through a trying experience. Strikes and industrial friction threatened to weaken the productive power of the nation at a moment when an agonizing call for munitions came out from the battlefields of France. There had been no industrial preparedness. England! organized her munitions industry without giving attention to terms of agreements with the labor groups. Premier Lloyd George came to the rescue, and as a consequence of the lack of preparation, England was compelled to go much further toward a recognition of labor’ s contention in the war than was really necessary. To-day the labor groups have a representation in the government, and the labor organisations are virtually a part of the government, with the manufacturer much less potent than before. No such step is to be undertaken here, because there is no real necessity for it, and very likely never will be.”

Unionism and laborism in Great Britain used the opportunity of war to accomplish the great purpose of laborism everywhere— securing recognition as a caste in the governing system of the nation. That is equally the purpose of American unionism, and it has failed. The failure is all the more deplorable and disastrous, as its preceding actions still remain as the policy of organized labor and thereby weaken the possibility of aggressive action.

However, war brings its own consequences and its own stimulus to action. The conditions may become ripe for the offensive, and the unions in self-defense may be compelled to act.

The war emphasizes the fact that the revolutionary Socialist must seriously assume the task of re-organizing the unions. Everywhere unionism failed even more miserably than Socialism. Without an aggressive union movement, there can be no aggressive Socialist Party and no aggressive action on a large scale.

And one very effective means of driving the existing unions forward to more aggressive action is to work for the unionizing of the unorganized and the unskilled. The unskilled are ripe for mass action, they are the pariahs of the existing order of things, they are the typical product of modern industry. Our action to awaken the unskilled will have decidedly revolutionary consequences.

We cannot expect much from organized labor, as such. It is simply working for a place in the governing system of the nation; it is dominated largely by skilled workers that profit from imperialism, and will act accordingly. Our one immediate hope is in the unskilled, and that portion of organized labor that is being menaced by the new industrial efficiency. The whole revolutionary movement must develop a new synthesis of organization, action and purposes, in accord with the new conditions of imperialism.

The Class Struggle and The Socialist Publication Society produced some of the earliest US versions of the revolutionary texts of First World War and the upheavals that followed. A project of Louis Fraina’s, the Society also published The Class Struggle. The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America. ‘In the two years of its existence thus far, this magazine has presented the best interpretations of world events from the pens of American and Foreign Socialists. Among those who have contributed articles to its pages are: Nikolai Lenin, Leon Trotzky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Lunacharsky, Bukharin, Hoglund, Karl Island, Friedrich Adler, and many others. The pages of this magazine will continue to print only the best and most class-conscious socialist material, and should be read by all who wish to be in contact with the living thought of the most uncompromising section of the Socialist Party.’

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v1n2jul-aug1917.pdf