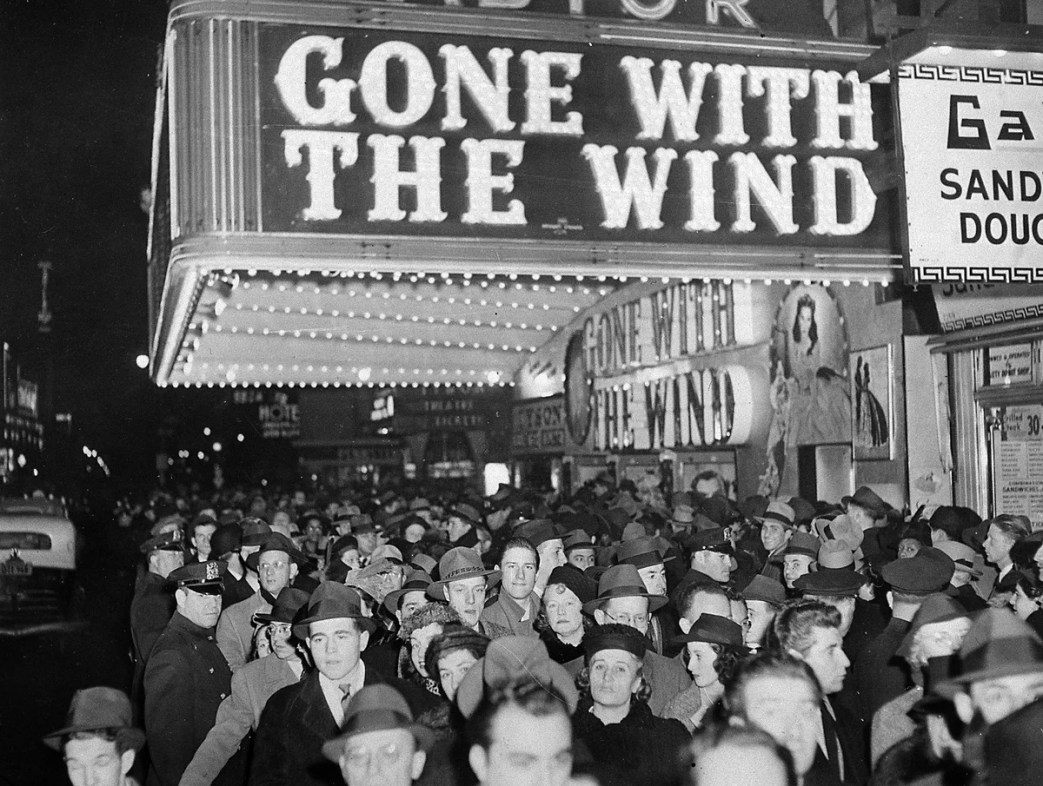

James Dugan, film critic for the New Masses, reviews ‘Gone With the Wind,’ one of the most famous and popular movies in U.S. history, on its premiere. No surprise; he gives it a thumbs down.

‘G’wan With the Wind’ by James Dugan from New Masses. Vol. 34 No. 2. January 2, 1940.

Hollywood’s march through Georgia makes Sherman look like a piker.

DYING men, it is said, see in their last moments a dense kaleidoscope of memories; their lives pass in review. Much the same thing holds for a dying society. The peculiar feudal past of the antebellum South, the decayed glory of a world well lost, has been an obsession with the American movies. The Birth of a Nation opened in 1915 in the same Broadway theater which now houses its successor in reactionary art, Gone With the Wind. A falsehood of such grandeur as this picture, a lie told with subtlety and persuasion in nearly four hours of expensive hokum, is more difficult to demolish than the ordinary tongue-in-cheek lies turned out every day in Hollywood. The myth of the Old South is widely believed; it is in fact one of the few things Hollywood believes in. This is fitting because it is the biggest myth of all.

Gone With the Wind does not present the crude white chauvinism of Griffith’s film, but the deeper, more contemptible racism of the “kindly” slaveholder. Ashley Wilkes, one of the principals, once remarks that he dislikes to use convict laborers because he cannot take care of them as well as slaves. When Scarlett O’Hara is criminally attacked by a Negro and white carpetbagger, it is the white man who physically manhandles her. The “white trash” has come to enjoy the same subhuman status as the Negro in the eyes of the wretched Southern ruling class.

The exception of the “loyal” Negro is worked to death in the story; one of Scarlett’s slaves repulses her white attacker. There is a Ku Klux Klan episode in the film, when the gentlemen officers ride out at night to terrorize the carpetbaggers, but it takes place offstage. There are several references to “darkies,” and to the cowardly, shiftless nature of the Negro servants. There is a pointed caricature of a land agent promising a crowd of Negroes forty acres and a mule. The Union Army and Abraham Lincoln come in for their share of the general abuse, and the audience is given the repeated impression that the Second American Revolution was a mistake.

I should like to take Mr. David O. Selznick out of his chartered skysleeper and rub his nose in the South of pellagra, of Jim Crow, of illiteracy, of opium-like poverty, of sharecroppers, of the modern Ku Klux Klan riding down unionists. This is the South his brave old world has hung on to, the logical result of the counter-revolution against reconstruction for which he and Miss Mitchell are the apologists.

The Southern revolution promised for a while to be set in motion again by the New Deal, but Jack Garner rode out at night in his white eyebrows, leading the gallants against it. Selznick’s Zouaves, riding hard from the West, have joined the pack. The next logical step is to prove that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were a couple of bums who worked cruel hardships on courtly Cornwallis and Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne. It could be done with a slight twist of John Hay Whitney’s checkbook.

Miss Mitchell’s noisome volume has been kept to with the piety of monkish copyists. I plead guilty to having studiously avoided it as I was busy carpetbagging during its phenomenal veneration. I am surprised to learn it is no ordinary piece of ancestor worship, but composed of skillful stereotypes, a certain drama and contrast, learned detail, and an air of injured righteousness. The agrarian aristocracy of the antebellum South, which rested airily on the misery of millions of black and white slaves, is now only wraith, pressed between leaves and dwelling in the smell of honored tombs. Miss Mitchell’s fantasy gains for the recognition of doom she gives her characters in the opening sequences as the first toasts are given to the defenders of Fort Sumter. Rhett Butler, the profiteer, says flatly the economic facts to a crowd of dashing imbeciles-the North has the arms, the industry, the men; you have only your arrogance-and this hindseen view dominates the Confederate officers throughout the story.

Structurally there are two stories-the wrong done a dreamlike civilization, and the story of Scarlett O’Hara. For over threequarters of the picture the first falsehood has its day, and then is dropped in the seventies· to work out the boresome saga of Scarlett and Rhett. Wan Southern heroines drop like overripe pears in this part, little girls are killed jumping their ponies, and the old lady gossips pursue their febrile ways. You can almost smell the decay in the atmosphere of these scenes; death is the actor in the red plush and baroque interiors of the post-Reconstruction period. The grand feudal civilization holds itself together with whisky and funerals and memories; it hasn’t even the strength for czarist orgies.

The last note in the film is an interesting one. Through her capriciousness Scarlett has lost her third husband and is at loss for something to turn to. The voices of the past, her father’s and her old lover’s, bid her to go back to the old plantation. Land is the only thing worth keeping. Could any landhog civilization state its case more frankly?

The picture is not all false, for some truth is necessary in these big myths; one must know how to read the self-revelation contained in its veil of perversion.

As entertainment there is little to be said for Gone With the Wind, particularly its dreary second reel. The technicolor is appropriately phony and the acting, with the exception of Vivien Leigh as Scarlett, is as wooden as the Mitchell characters.

The film has a great role to play in a new period of reaction, just as The Birth of a Nation signalized the first distinguished enlistment of the movies for purposes of death. Desperate reactionaries will feel their spirits soar in the face of this comforting past they would recapture; from it will naturally be inspired all the dark and murderous deeds needed to put down the people once again.

The ruling class cannot face the future; they point us toward the miserable past. Abraham Lincoln and Emancipation and the stabilization of Southern economy, the progress for which my great-grandfather died in The Wilderness, is spit upon in this movie. Why did the hoarse Abolitionists cry this outrage of slavery in the land, John Brown stand up wildeyed in Kansas, and Lincoln face his ordeal? That we should learn eighty years from them that the Old South was beautiful? I think not. Hollywood has taken this lie seriously and I think progressive America will too.

Not a movie reviewer that I have read in the great objective press of the nation has dared to mention that Gone With the Wind deals with American history. With nice critical whereases the boys have begun with the assumption that it’s all true, and then they juggle the customary adjectives about the acting, length of the picture, direction, color, etc., and earn the boss a night’s repose.

I offer myself to the press for interviews on my reaction to Gone With the Wind. In all modesty I can’t expect a big play since nobody told me to “blister” the picture and no cables came in from Stalin asking to read my copy before it went to press. If MGM has an ounce of. gratitude it will give Howard Rushmore a job at once. Precious few others will hit the sawdust trail, I suspect.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1940/v34n02-jan-02-1940-NM.pdf