‘Women Workers of Porto Rico’ by Nina Lane McBride from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 17 No. 12. June, 1917.

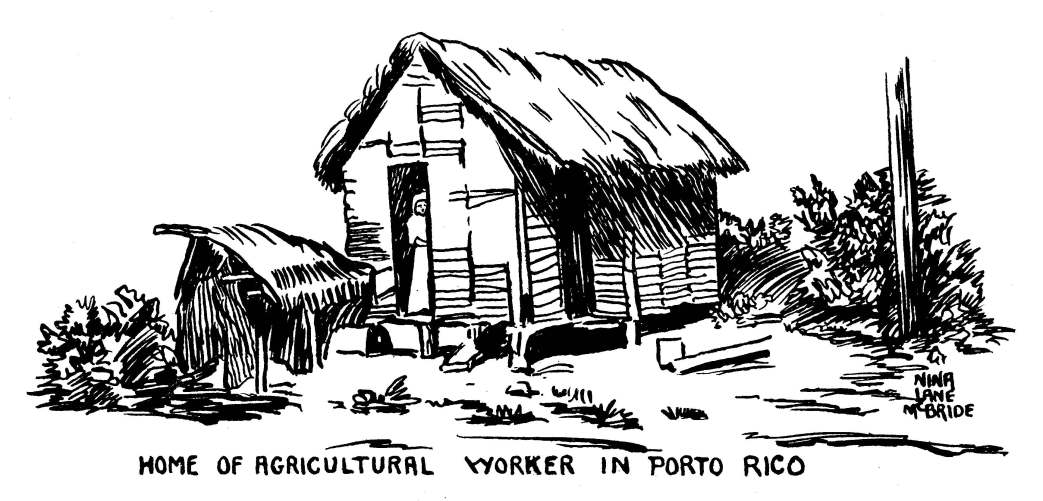

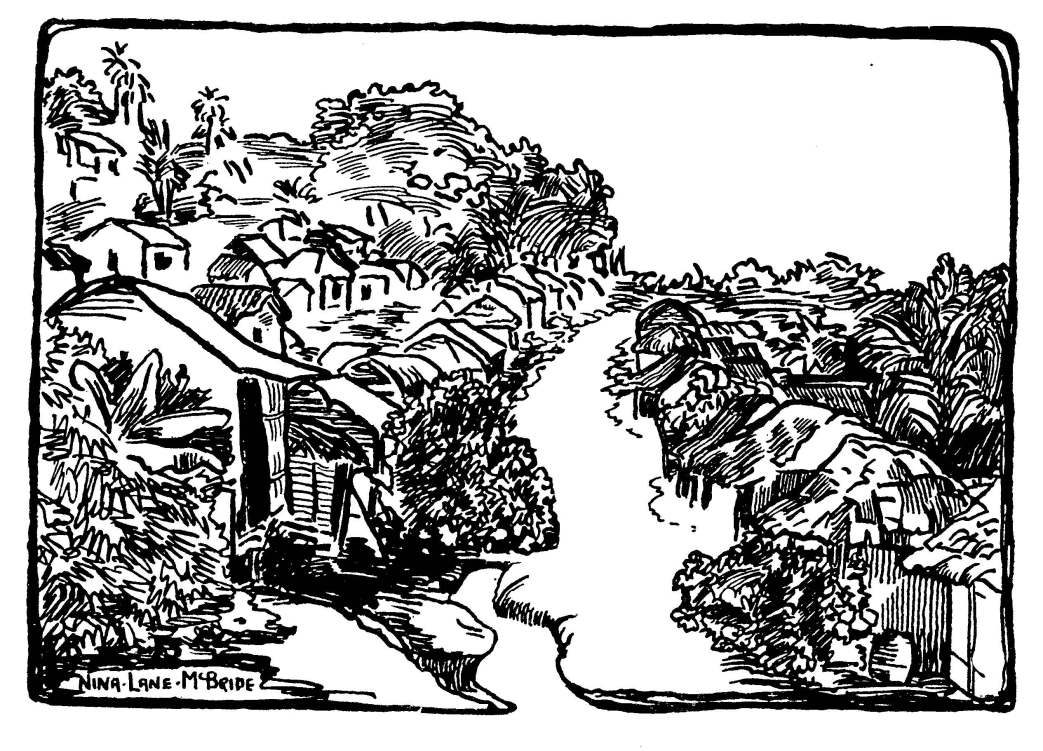

WHEN the sugar coated hand of the United States Government shook Porto Rico loose from the iron grip of Spain, the annual production of the island was about forty five million dollars. Since the American occupation, the production has increased to one hundred and fifteen million dollars, and great strides in the sanitary conditions of the island have been made, such as the improvement of the water and sewage systems of towns and cities, improved country roads, etc. Wealth, and modern industry are everywhere. This is the sum and substance of the report given out by the Governor of the island, to members of the United States Senate, when the Porto Ricans were seeking the passage of the Organic act, known as the Jones Bill, called by some of the knowing ones, the “Bill Jones.” In fact, nearly everything on the island has changed for the better, except the condition of the working people, which has remained the same, with the exception that they have American prices of commodities to meet, and are beginning to organize themselves, to meet American conditions. Like the butterfly, crawling from its chrysalis, the people of Porto Rico are creeping slowly along the path of progress against the high wind of economic conditions, equipped at the present time with antiquated ideas of organization, from which in time will, no doubt, develop a strong industrial organization, which will free them from their bondage.

The women of Porto Rico, feel the coursing of the new life thru the arteries of the times, more keenly than do the men, after the centuries of servitude to church, state and employers, and are rapidly taking advantage of opportunities afforded. In nearly every industry the workingwomen are organizing themselves into craft unions and while their forces are in a sense divided, those working in the same industry, do not feel that their contracts with their employers are particularly binding, and if one set of women strike, the others whether organized into a union or not, can be counted upon to go out with them.

It has happened that women in one factory have gone on strike, and have marched from the factory into town, pulling out women workers as they marched, taking them from their work at all occupations, even those in domestic service, until by the time they had reached the Plaza, they had swelled their ranks to two thousand strong. When these women strike, they strike; they are tenacious fighters, and soft words and promises do not often fool them. In many cases they have forced the employers to raise wages, just by threatening to strike. The women working in the Macaroni Factories organized themselves without affiliating with any labor organization, and struck for a twenty-five cent a day raise from a wage of thirty-five cents for a ten hour day, and won. Working conditions for the women are so terrible, that when thru desperation a desire for freedom is born, their struggle for the attainment is magnificent. As yet, they can see only a better form of capitalism, they cannot visualize an industrial democracy.

Working conditions for the telephone operators, can hardly be imagined. The switch boards are placed in the home of the operator and she is supposed to be on the job night and day, to answer the call, and make connections. The ringing of the bell keeps the whole family awake at night, and on a nervous tension all day. It is estimated by the labor organizations of Porto Rico, that fully twenty-five per cent of the operators are tubercular, due to the close confinement demanded by their work. The operators of these home stations receive from fifteen to twenty dollars per month.

Stenographers receive from eight to t~n dollars per week, and are the best paid women workers on the island. Teachers receive from thirty-five to sixty-five dollars per month for a school year-nine months. Distinction is made between native teachers and American teachers, doing the same class of work and teaching the same subjects. The American teachers receive ten dollars a month more than does the native teacher.

The woman who works in domestic service, knows drudgery in its worst form, and degradation unspeakable. She works from early morning until late at night, with no days for rest, and no holidays. Her meals are furnished by her master, and her wages average three dollars per month.

The average straw hat workers, doing piece work, working a day of ten hours, six days a week, receive from two dollars and seventy-five cents to three dollars per week. Those doing the very finest work, working the same number of hours, receive from three to four dollars a week. Dress makers, working from 8 a.m. until 10 p.m., average four and five dollars per week. The average store clerk receives three and a half to four dollars per week. Five dollars a week is the highest wage paid for a day of nine hours.

In the cane fields the women work in the hot sun, always moving about, spreading seed, cleaning up litter, etc. In fact, acting as helpers to the men who cut and load. For this work they receive forty-five and fifty cents per day. In the pineapple canning factories, the women and children are paid by the hour, their wages being two and a half cents per hour. They work as long as they are able, that they may make a few extra cents.

Conditions in the cigar factories are very bad. There is only one factory on the island which is considered sanitary by the workers. The factories are overcrowded with workers, and in some of the factories to have sanitary conditions, over half of the workers should be dispensed with. An insular ordinance was passed to improve the sanitary conditions in the factories, and the owners were given ten years in which to make the changes. Needless to state, the ten years have not yet elapsed. The strippers, which are women, are paid twenty cents per bunch for their work. By working hard, they can make from fifty to sixty cents per day.

Coffee is picked during the rainy season, and the women work in the fields in the pouring rain, barefooted and drenched to the skin, with their little children working by their sides. The mud gets very deep in these fields, and the work is not only hard, but fraught with great danger to the lives of the pickers, as land slides are not infrequent. The fields are on the mountain sides, and the heavy rains loosen the soil, which slides, taking plantation and workers with it. These women are paid by the measure. One measure brings thirty-five cents, and with the help of baby hands can be filled in from nine to ten hours.

Reports tell us, that this has been a very prosperous year in Porto Rico. The sugar companies alone, are said to be making a profit of one hundred and fifty per cent. Prices of commodities are a little higher than in the United States. As one capitalist publication stated recently, “San Juan today is certainly a good American city; it is vastly more American than many parts of the continental United States, etc.” I may add, that Porto Rico today, is certainly a good American Island. Fine sanitary conditions, great wealth, and lots of profits-for the other fellow.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v17n12-jun-1917-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf