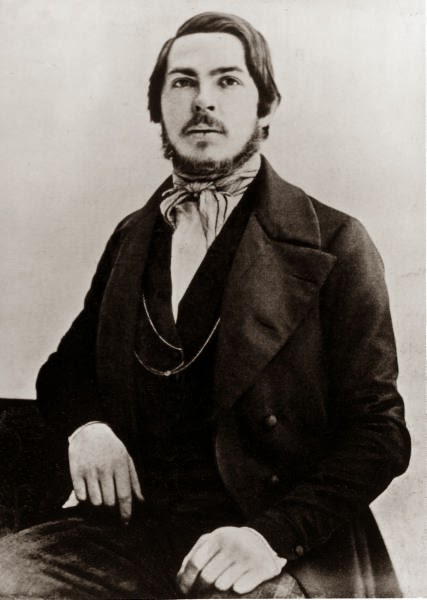

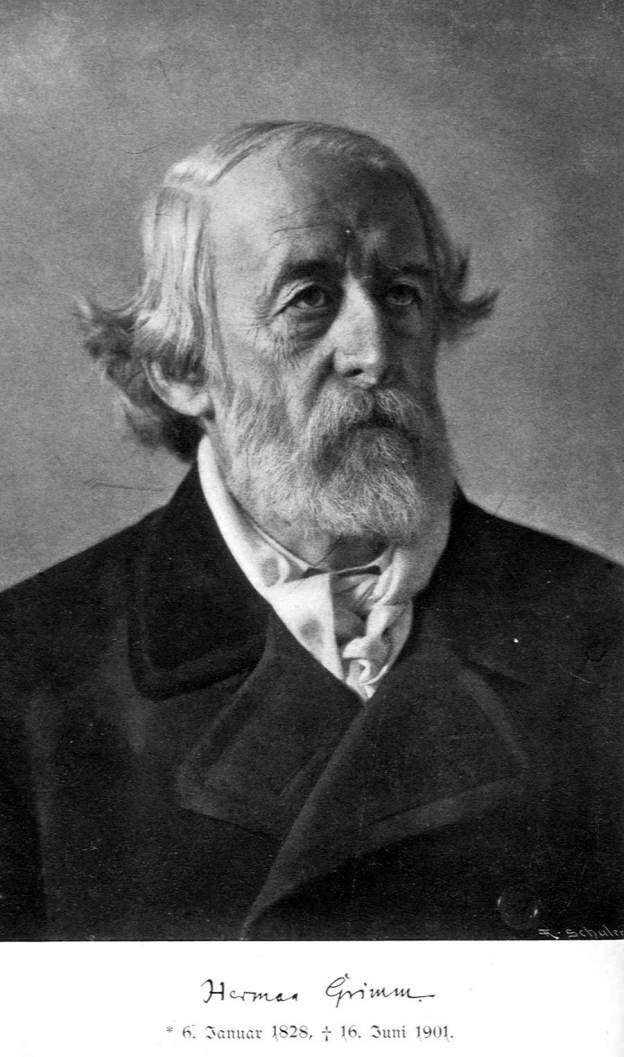

An uncovered review of Herman Grimm’s biography of Goethe by a keen 26-year-old Friedrich Engels for the Deutsche Brusseler Zeitung in 1847, which serves as a critique on ‘True Socialism.’ With excerpts of letters to Marx, who is likely co-author, for further context. Marvelous.

‘Engels on Goethe’ (1847) from the New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 3. September, 1932.

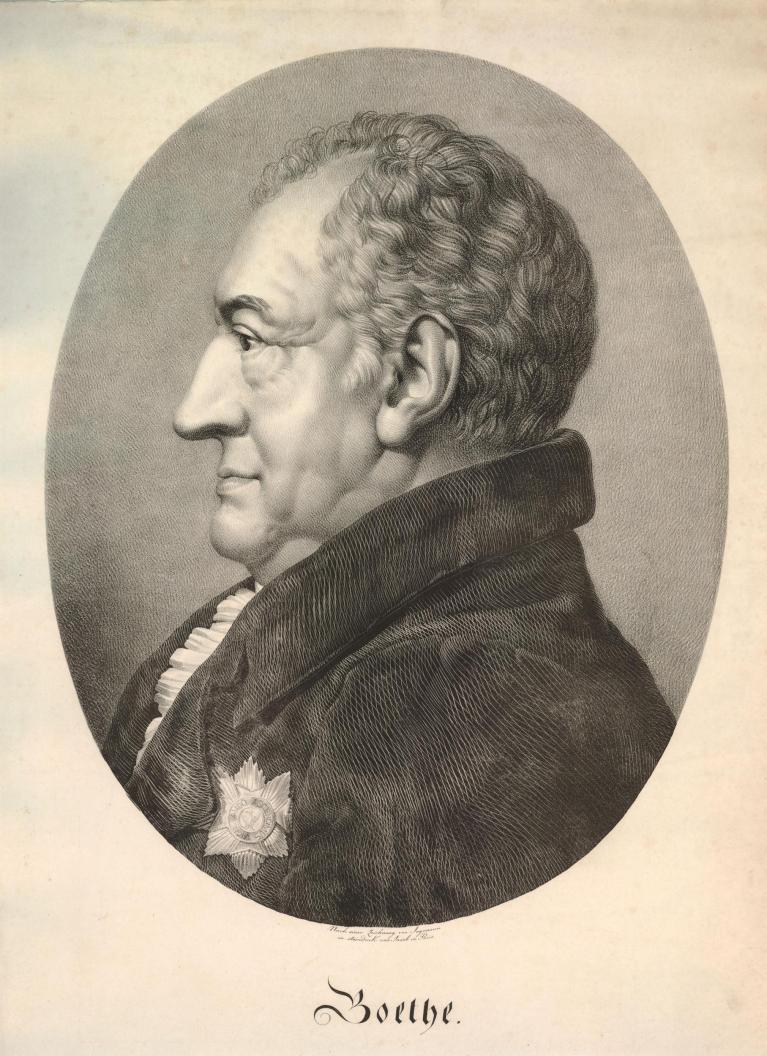

The German journal, Die Links-Kurve, has just published an article on Goethe written by Engels in 1847 for the Deutsche Brusseler Zeitung. This article was practically forgotten. It was excluded from the Nachlass of Marx and Engels by their editor, Mehring, who considered it unimportant and out-of-date. But in the current celebration of Goethe’s centenary (in Russia as well as in Germany, and by the working class as well as by bourgeois intellectuals) the views of Engels have been justified even in what seemed to be no longer timely polemical aspects. His article is a critique of an adulatory book on Goethe by a “truesocialist,” Grim, who “glorified all the philistinism of Goethe as human, and made the Frankfurt and office-holding Goethe the ‘real man’, while he overlooked or even bespat all that was colossal and genial in him. To such a degree that this book furnishes the most splendid proof that the man— the German provincial” (Letter to Marx, January 15, 1847). Grim wished to present Goethe as a good German, an idealistic, humanitarian bourgeois, just as to-day the irreligious, international Goethe is held up to German youth by fascist professors and critics as a model Nazi, a protestant, a patriot and. a national-socialist. (The Goethe-meetings of revolutionary proletarian groups are accordingly suppressed by the socialist police of Berlin). In showing how the socialist, Grim, has converted Goethe entirely into a reactionary German petty bourgeois, Engels has disclosed the bourgeois roots and interests of liberal socialism. Engels’ criticism should not be confounded with the attacks of those who reject Goethe completely on one count or another. Such was the method of the Frankfurt literary journalist, Ludwig Boerne, a converted Jew who condemned Goethe for not being as liberal as himself; and of the “Franzosenfresser,” Menzel, who denounced the poet as unchristian and unpatriotic. Engels does not deny the genius or importance of Goethe because of his class-limitations. On the contrary, it is Engels’ chief point that even so great a genius as Goethe could not overcome the weakness of his class, and that the artist, as artist, was affected by his compromise with bourgeois society. If Engels did not formulate systematically the specific value of Goethe and his works for the revolutionary working class, it was because, as he himself says, his immediate problem restricted him to the analysis of Grim’s thoroughly provincialized, middle-class hero.

“Naturally we cannot speak in detail here of Goethe himself. We are calling attention to only one point. Goethe stands in his works in a double relation to the German society of his time. Sometimes he is hostile to it: he tries to escape its odiousness, as in the “Iphigenia” and in general during the Italian journey; he rebels against it as Gotz, Prometheus and Faust; he pours out on it his bitterest scorn as Mephistopheles. Sometimes, on the contrary, he is friendly to it, accommodating, as in most of the tame Epigrams and in many prose writings, celebrates it, as in the Masquerades, even defends it against the intruding historical movement, particularly in all the writings where he happens to speak of the French revolution. It is not only single sides of German life that Goethe accepts, as opposed to others that are repugnant to him. More commonly it is the various moods in which he finds himself; it is the persistent struggle in himself between the poet of genius, disgusted by the wretchedness of his surroundings, and the Frankfurt alderman’s cautious child, the privy-councillor of Weimar, who sees himself forced to make a truce with it and to get used to it. Thus Goethe is now colossal, now petty: now a defiant, ironical, world-scorning genius, now a calculating, complacent, narrow philistine. Even Goethe was unable to overcome the wretchedness of German life; on the contrary, it overcame him, and this victory over the greatest German is the best proof that it cannot be conquered by the individual. Goethe was too universal, too active a nature, too fleshly to seek escape from this wretchedness in a flight, like Schiller’s, to the Kantian ideal: he was too sharp-sighted not to see how this flight finally reduced itself to the exchange of a commonplace for a transcendental misery. His temperament, his energies, his whole spiritual tendency directed him towards practical life, and the practical life that he met with, was miserable. In this dilemma, — to exist in a sphere of life that he must despise, and yet to be fettered to this sphere, as the only one in which he could fulfill himself — in this dilemma Goethe continually found himself, and the older he became, the more did the powerful poet retire, de guerre lasse, behind the insignificant Weimar minister. We are not throwing it up to Goethe, d la Boerne and Menzel, that he was not a liberal, but that he could even be a philistine at times, not that he was incapable of any enthusiasm for German freedom, but that he sacrificed his occasionally irrepressible, sounder aesthetic feeling to a small-town aversion from every great contemporary historical movement; not that he was a courtier, but that at the time when a Napoleon was cleaning out the vast Augeanstables of Germany, he could manage with a ceremonial seriousness the most trivial affairs and the menus plaisirs of one of the most trivial little German courts. In general, we are reproaching him neither from moral nor from partisan standpoints, but chiefly from aesthetic and historical standpoints; we are measuring Goethe neither by a moral, nor by a political, nor by a “human” standard. We cannot undertake here to represent Goethe in connection with his whole age, with his literary forerunners and contemporaries, in his development and social position. We are therefore limiting ourselves simply to the statement of the fact.”

Engels then proceeds to analyze the claims of Goethe to the respect of radical thinkers, for Grim has made Goethe a truesocialist, a Proudhonist and even a Communist, by a silly manipulation of excerpts. Actually, Goethe’s “radical” criticism of society is on the level of sentimental lamentation over the breakup of the family, the cruelty of the machine, and the passing of the classical virtues, which comfort humanists. When Goethe asks in a trivial poem, —

O child, consider, whence these gifts?

You can have nothing from yourself. —

Oh, all I have is from papa.

And he, where does he get it? — From grandpa. —

Oh no! for how did grandpa get it?

He took it,

Grim triumphantly concludes that “property is theft” and that Goethe is indeed a Proudhonist. In the immature ejaculations of Werther he discovers “a deeply incisive criticism of society” that prepared the way for the French revolution.

But “in order that Goethe’s attitude to the revolution might appear justified,” says Engels, “Goethe must naturally stand above the revolution and have overcome it already before it existed. We therefore learn on p. xxi (of Grim’s book) that “Goethe was so far ahead of the practical development of his time, that he believed he could only stand aloof or rebuff it’. And on p. 84, referring to “Werther,” which, as we saw, already contains the whole revolution in nuce: “History stands at 1789, Goethe stands at 1889’. Likewise Goethe ‘in a few words does away thoroughly with the whole noise about freedom’ in that already in the 1770’s he publishes an article in the Franfurter Gelehrten-Anzeigen that does not speak at all of the freedom demanded by the ‘fanatics’, but only indulges in several general and rather sober reflections on freedom as such, on the concept of freedom. Further: because Goethe in his doctor’s dissertation sets up the thesis that every lawgiver is really obliged to introduce a definite cult — a thesis that Goethe himself treats merely as an amusing paradox, provoked by all sorts of small-town Frankfurt church brawls (which Herr Grim himself cites) — therefore ‘the ‘student Goethe wore out good shoe-leather on the whole dualism of revolution and the modern French state’. It seems as if Herr Grim has inherited the worn-out soles of the ‘student Goethe’ and soled with them the seven-league boots of his “Social Movement.”

“Now, of course, we begin to understand Goethe’s utterances with regard to the revolution. It is clear now, that he, who stood far above it, who had already ‘disposed’ of it fifteen years before, ‘worn out his soles on it’, and anticipated it by a century, could have no sympathy for it, or interest himself in a race of libertarian fanatics, with whom he had already settled in ’73. It is child’s play for Herr Grim now. Goethe can set ever so banal saws to elegant verse, reason ever so narrowly and crassly about them, shudder ever so provincially before the great debacle that threatens his little poet’s nook, he can behave as pettily, as cowardly, as obsequiously as possible, he cannot carry it too far for his patient commentator. Herr Grim lifts him on his tireless shoulders and carries him through the muck; he even claims all the muck for True-Socialism, if only to keep Goethe’s boots clean…

“What conclusions on ‘the essence of the man’ do we get from Goethe’s criticism of society and the state through Herr Grim?

“In the first place, ‘the man’ (according to p. 264) has a very decided respect for the ‘educated classes’ in general, and a proper deference towards the higher nobility in particular. And then, he is distinguished by an enormous fear of any great movement of the masses, of every energetic social action, at whose approach he either creeps away timidly to the corner of his stove or flies hastily from it with all his baggage. As long as it lasts, the movement is ‘a bitter experience’ for him; it is hardly over, before he plants himself again all over the ring and administers knockout blows with a Herculean hand, and he finds the whole business ‘infinitely ridiculous’. He therefore clings heart and soul to ‘welldeserved and well-employed possessions’; besides he has a very ‘domestic and peaceful nature’, is self-sufficient and modest, ‘and doesn’t wish to be disturbed in his small, quiet pleasures. ‘The man likes to live a narrow life’ (p. 191, so reads the first sentence of the ‘second part’); he envies no one and thanks his creator, if he is left in peace. In short, ‘the man’, who we have already seen is a born German, little by little begins to resemble a small-town German to a hair.

“To what, in fact, does Goethe’s criticism of society, via Herr Grim, reduce itself? What does ‘the man’ find to expose in society? First, that it does not correspond to his illusions. But these illusions are precisely the illusions of the ideologizing, especially the youthful, philistine — and if the philistine reality does not correspond to these illusions, it is only because they are illusions. They therefore correspond all the more completely to the philistine reality. They are distinguished from it only as the ideologizing expression of a condition is generally distinguished from this condition, and there can hence be no further question of their realization. Herr Grim’s glosses on Werther are a striking example.

“In the second place, the polemic of ‘the man’ is directed against everything that menaces the German philistine regime. His whole polemic against the revolution is that of a philistine. His hatred towards the liberals, the July revolution and the protective tariffs is most unmistakably revealed as the hatred of the depressed, conservative small-townsman towards the independent, progressive bourgeois…

“‘When we find a place somewhere in the world’ says Goethe, summarized by Herr Grim, ‘in which to rest with our possessions, a field to feed us, a house to cover us, isn’t that a fatherland?’ ‘He has taken these words out of my mouth!’ cries Herr Grim (p. 32). ‘The man’ wears a reding ote a la proprietaire , but he also looks like a thoroughbred grocer.

“The German burgher is at best a fanatic for liberty for a short time in his youth, as everyone knows. ‘The man’ has the same peculiarity. Herr Grim mentions with pleasure how Goethe in his later years ‘condemns’ the ‘thirst for liberty’ still spooking around in Gotz, this ‘product of a free and ill-mannered youth’, and even quotes the cowardly retraction in full. What Herr Grim understands by liberty, can be gathered from the fact that he even identifies the liberty of the French revolution with the Swiss Confederation of the time of Goethe’s Swiss journey, therefore modern constitutional and democratic freedom with the patrician and guild domination of the mediaeval imperial cities and moreover with the primitive Germanic barbarism of cattle-breeding Alpine tribes. The montagnards of the Berne highlands are not even once distinguished in name from the Montagnards of the National Convention…

“The bourgeois cannot live without a ‘beloved king’, a dear father of his people. ‘The man’ also can’t. Hence Goethe has an ‘excellent prince’ in Karl August. The gallant Herr Grim who still raves about ‘excellent princes’ in 1816!

“The bourgeois is interested in an event only insofar as it directly affects his private affairs. ‘Even the events of the day were foreign objects to Goethe, which could either disturb or further his bourgeois comfort, and could also claim his aesthetic or human, but never his political interest’. ‘A thing accordingly wins the human interest of Herr Grim, if he sees that it ‘disturbs or furthers his bourgeois comfort’. Here Herr Grim perhaps avows openly that bourgeois comfort is the chief thing to ‘the man’…

“Wilhelm Meister is a ‘communist’,’ i.e. ‘in theory, on an aesthetic level’ (!!) p. 254. ‘Er hat sein’ Sach auf Nichts gestellt, und sein gehort die ganze Welt’ p. 257 (He cared for nothing in the world, and the whole world was his). Naturally he has enough money and the world belongs to him, as it belongs to every bourgeois, without his having to take the trouble to become a ‘communist on an aesthetic level’. — Under the auspices of this ‘nothing’ for which Wilhelm Meister cared, and which, as may be seen on p. 256, is a far-reaching and substantial ‘nothing’, life’s jag is abolished. Herr Grim ‘drinks down all the dregs, without a jag, without a headache’ …‘this song (I cared for nothing in the world…) will be sung when mankind has become worthy of it’; but Herr Grim has reduced it to three stanzas and has cut out the passages unsuitable for the young and for ‘the man’…

“We have only one more observation to make. If in the preceding lines we have considered Goethe from only one side, that is merely the fault of Herr Grim. He does not represent Goethe from his colossal side at all. About all things in which Goethe is really great and a man of genius, he either slips hastily by, as on the Homan Elegies of the ‘libertine’ Goethe, or he pours out on them a broad stream of trivialities, which only shows that he does not know what to do with them. On the contrary, he searches out, with an industry otherwise uncommon in him, all the petty philistine remarks, all the meannesses, collects them, exaggerates them in true literary manner, and rejoices every time he can support his own narrowness with the authority of the often disfigured Goethe.

“Not the yelping of Menzel, not the narrow polemic of Boerne, was History’s revenge for Goethe’s constant denial of her, whenever she confronted him eye to eye. No,

As Titania found Nick Bottom in her arms

In magic fairyland,

so did Goethe find Herr Grim one morning in his arms. The apology of Herr Grim, the warm thanks which he stammered to Goethe for every philistinish word, that is the bitterest revenge insulted History could inflict on the greatest German poet.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1932/v08n03-sep-1932-New-Masses.pdf