‘The Life of a Railroad Trackman’ by a Trackman from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 9. November, 1919.

One of the blackest pages in the history of the American railroads contains the story of the track laborer. It is a tale of almost unbelievable degradation and misery. The railroads have often been compared to arteries through which the life of a nation pulsates, and it is a well known fact that an efficient transportation system is the greatest asset of a modern people, but the men whose labor made the marvelously quick development of a continent possible, have been the lowest paid and the most inhumanly exploited of all the workers in the country. In our age of electricity and steamheat, of spacious dwellings and all the modern conveniences for those who neither toil nor spin, but live on the sweat and blood of those who carry on the productive labor of society, in this wonderful age of progress the men whose toil safeguards the life of the passengers as well as the transportation of the necessities of life, had to exist in hovels, which were often not even a protection against the elements. It is a story of graft and exploitation, of vermin and filth, of stomach-robbing boarding contractors and ghoulish employment sharks.

The track laborers are divided into section and extra gangs. The section gangs consist of from two to eight or ten men, while the extra gangs often have as many as 60 and 70 men in one camp. There is generally an extra gang on every division, while the section men are stationed six or eight miles apart.

The living quarters of the section men consist mostly of a small shanty or an old box car taken off the trucks and set on the ground. At some sections the laborers can board at the section boss’s house, but in most places the men have to do their own cooking. With six or eight men trying to cook their meals on one stove it is necessary for some to get up as early as 4 o’clock in the morning in order to get a chance to cook their breakfast. On the sections on deserts and in mountain regions it is sometimes hard to get bread from the nearest town, and not very many stoves found-on sections can be used for baking. Some of the foreign-born section men bake their bread in holes in the ground, while many live on baking powder biscuits and hot cakes. The life of a section man is not an easy one even now under the eight hours a day system, but when a day’s work consisted of ten long hours of hard, backbreaking labor on the track his existence surely was a miserable one. When times were hard and work scarce the section men often had to turn part of their scanty earnings over to the foreman, who would pass the money on to the roadmaster, but the foreman also had to come across if he wanted to hold his job. As the story goes there were divisions where only a section foreman with a pretty wife could hold his position providing he did not resent the visits of certain officials while the wife was alone in the section house.

Bad as conditions are on the sections, in the extra gangs it is still worse. Although the eight-hour day is in effect, the scarcity of labor in certain districts and the incessant agitation of the members of the I.W.W. on the jobs, have brought about a few changes, but the extra gangs today are still in a deplorable condition. The camps consist of strings of old and dilapidated box cars with leaky roofs and broken floors with big cracks in the walls partly filled with rags and old paper. Some of the cars are fitted up as kitchen and “dining” cars, while others are turned into bunk cars. From ten to sixteen men have to make their homes in cars which are often so low that a tall man cannot stand up straight. There are no baths, no washrooms, and in many camps not even a toilet. In the eastern part of the country blankets are furnished, but they are never sent to the laundry or cleaned. Year after year they are passed on from man to man. I have seen men in those camps in the various stages of consumption, with venereal diseases, with the marks of syphilis in their faces, but when they left camp their blankets were turned over to somebody else. Lice and other vermin were always plentiful. Before the Government took over the railroads and abolished all Sunday work, there was no such a thing as Sunday in an extra gang. The work went on day after day, with no rest and no recreation. This also helped to a great extent to increase the filth and the swarms of vermin in the camps. If a man laid off a day to wash his clothes he would run chances of going into the hole on his board and commissary bill. In the summer time a man could take an empty coal oil can and go out after supper and “boil up,” as this process of delousing is called in the camps. He would build a fire out in the open and boil his clothes and so destroy his “live stock” and for a night or two he would be able to sleep undisturbed. But in the winter time the deep snow and the scarcity of firewood would often prohibit the “boiling up” and the ever-increasing swarms of vermin would make the miserable existence of those men still more unbearable. The railroads of the west never furnished bedding on their extra gangs and some did not even furnish straw ticks or straw. If a man did not pack a mattress and a bundle of blankets around with him he had to sleep on the bare boards. And many a man slept on bare boards. In Northern Pacific extra gangs at Sand Point, Idaho, in January, 1919, I have seen six men in a bunk car sleeping on the hard boards with nothing under them or over them but three gunny sacks. Not three gunny sacks apiece, but three sacks for six men.

The board on extra gangs on most of the railroads is supplied by contractors. Cooks and kitchen help are hired by them, and the men’s board bill is taken out of their pay by the railroad company. Those boarding contractors are in the business for all the money they can make out of it, and, of course, the stomachs of the workers have to suffer. Half decayed meat, wormy fruit and adulterated food and substitutes are daily on the bill of fare. Although there are several of those stomach-robbing concerns, like Brogan & White, Miller, the Western Commissary Company, Fogg Bros., Grier, and other notorious outfits, the food is very much alike. Some seem to have an inexhaustible supply of “gut and liver,” while others make a specialty of “lawnmowers and gatelifters” (cowslips and pig snouts). As the conditions in those camps are fairly well known amongst the migratory workers, they will only “ship out” to an extra gang when they can’t find anything else. The railroad companies furnish free transportation, and while some companies conduct their own employment offices, most of the jobs have to be bought from the sharks. Their fees vary with the conditions of the times. The more unemployed the higher the fee. The miserable life of a worker in those camps makes it almost impossible for a man to stay for any length of time. A week or two is about the average. And this is what makes it so hard to organize those out fits. Many of the old timers, who have been forced to live this life of degradation for many years have degenerated to such an extent that they don’t seem to care about cleanliness any more and they are indifferent towards the educational campaign of the I.W.W. But in spite of all there are more and more trackmen coming into the I.W.W. every day, and there have been some fine showings of solidarity in some of the extra gangs of the Northwest. There is really no opposition toward the movement in those gangs, only indifference. Men who have been driven from pillar to post all their lives and have lost all faith in humanity, are hard to convince that the I.W.W. is not some kind of a graft, but their only hope of delivery from a dreary, miserable existence. But slowly they are beginning to see that the only way to break up the unholy trinity of grafting officials, stomach-robbing boarding contractors and fatbellied employment sharks is to organize in the One Big Union of all who toil. Only through organizing and organizing right, will the track laborer ever be able to do away with the intolerable conditions which have made millions of dollars for the employment sharks and other highly respectable citizens who were in on the deal. For the rottener the camps the shorter the time men would be able to stay, and the money would roll into the tills of the employment sharks in a steady stream to be split up with the men who were responsible for the bad conditions in the camps.

Trackmen, wake up! Organize into Railroad Workers’ Industrial Union 600 of the I.W.W. and let us speed the day when all workers on the railroads will be enabled to live on clean, wholesome food and have the comforts and recreations of human beings.

(This article will immediately be issued as a leaflet by No. 600. Procure some and spread them. Send in your orders at one for a bundle to C. N. Ogden 1001 W. Madison St., Chicago, ILL.)

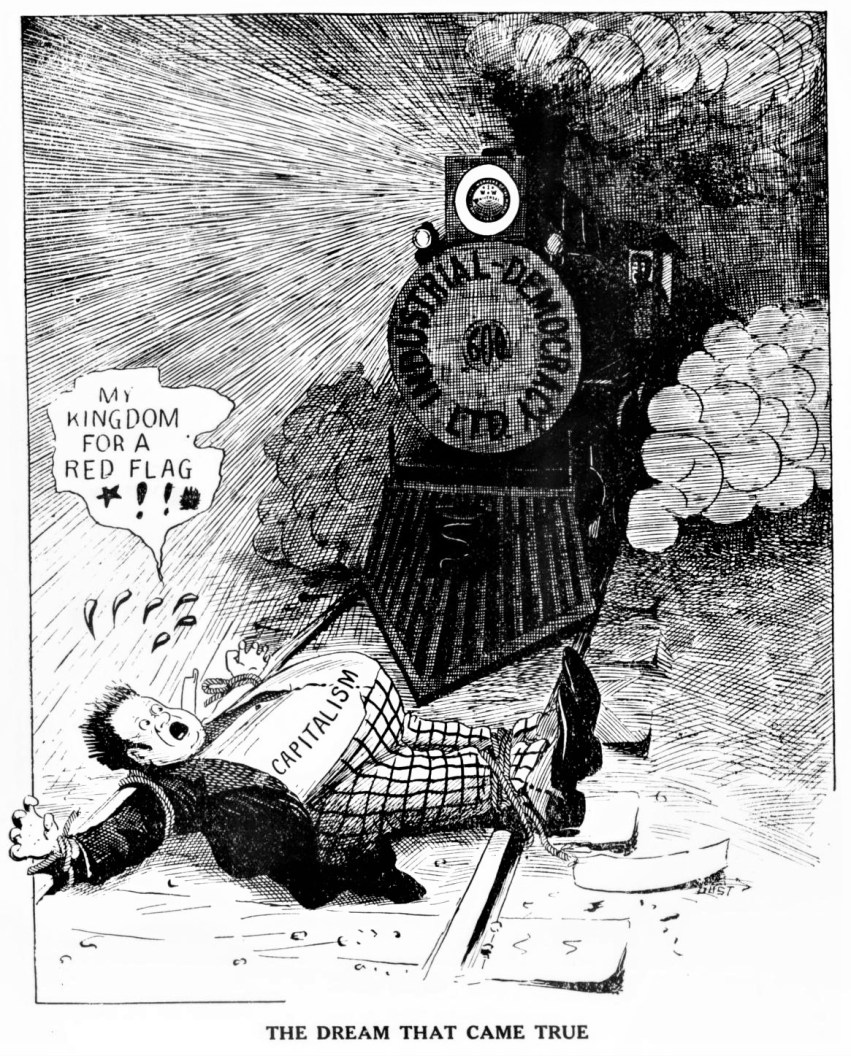

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-11_1_9/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-11_1_9.pdf