‘In Memory of the Commune: A Working Class Demonstration in Paris’ by Phillips Russell from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 15 No. 2. August, 1914.

I WAS curious to see what a big working class demonstration in Paris was like, so when Victor Dave, white-haired veteran of the International, told me, soon after my arrival in Paris on May 15 of this year, of the approaching memorial day in honor of the Commune on May 24, I made a note of it.

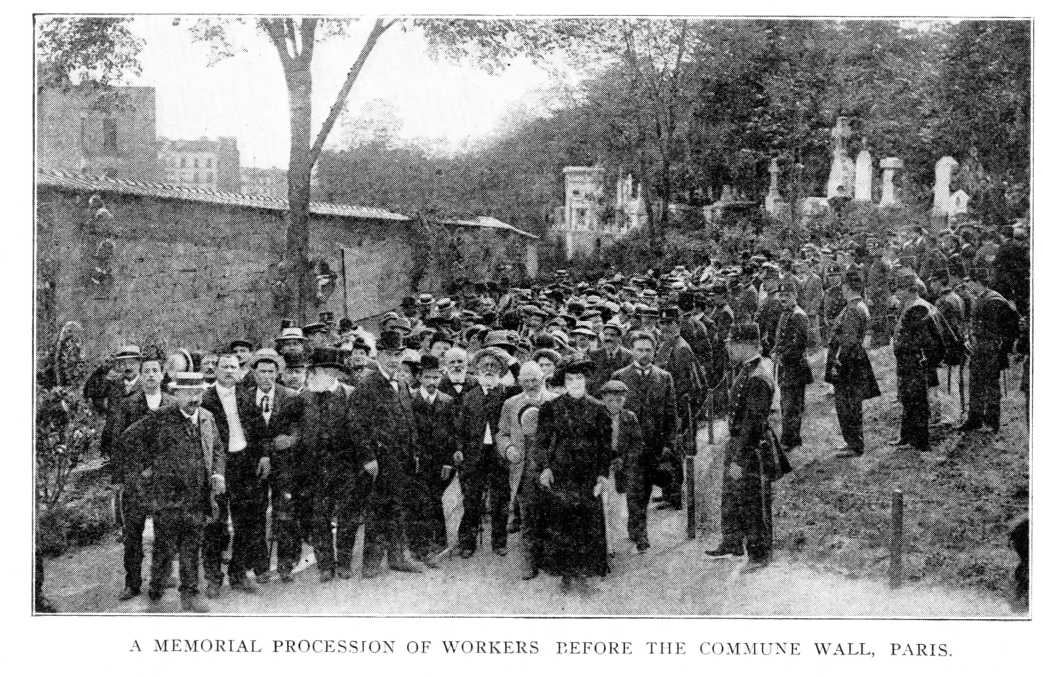

Sunday, May 24, came clear and sun lit, the trees of the great boulevards wearing the fresh, glowing green that they do only in Paris in the spring. In the afternoon I tried to find my way to Pere Lachaise cemetery, where fell the martyrs of the Commune but every bus and tram was crowded and I was forced to take a roundabout way, which brought me to the cemetery late. But I found I was in plenty of time. The procession into the cemetery had just begun, and as far down the street from the gate as the eye could see stretched a long, thick, patient line, spotted with crimson banners that tossed and flapped in the warm breeze. Thirty, perhaps forty, thousand there were–all working men and women; yes, and children, too.

Motion-picture operators were grinding away furiously as the great line moved steadily into the gate. A vast throng of the idly curious stood silently around, kept back by heavy lines of police. There seemed to be more police than demonstrants. At the entrance to the cemetery stood a group of silver-trimmed, heavy paunched police officials, contemplating the streaming throng with the cold, watchful gaze characteristic of policemen and other carnivorous animals when in the presence of their prey.

As I pushed my way toward the cemetery gate, already I could feel the electric tension that is so strong in the atmosphere whenever a great crowd of working people gather under the surveillance of the uniformed representatives of their masters.

Going well back toward the end of the line, I slipped through the police line and joined a group of young people who marched behind a red banner showing that they were a Circle of Socialist Students of the twentieth arrondissement, or precinct. As I took my place in line, a clear baritone voice far in the rear started up, of course in French, the tune of the International:

“Arise, ye prisoners of starvation,

Arise, ye wretched of the earth.”

Other voices quickly joined. I could hear the song advancing up the line like a roaring wave. Soon we were all singing it. We could hear it coming from far in the center of the cemetery. Ordinarily the police do not permit this song to be sung in the streets of Paris, but this crowd was too big to be interfered with, so the police kept quiet, betraying their uneasiness by shifting from one foot to the other and twirling their long mustachios.

Soon we were inside the cemetery, the thick trees throwing a damp gloom over the rows of silent tombs. Up a steep declivity we pushed, winding round and round like a gliding snake. The police were everywhere. Not. only did they line the course solidly, but clusters of them, on foot, bicycles and horses, could be seen half concealed behind clumps of trees or high tombs.

Every sight of these partly hidden groups was greeted with jeers by the crowd and by loud shouts of a phrase which puzzled me until, finally, I made it out as “Les trois ans-hou! hou! Les trois ans-hou! hou!” This cry refers to the much-agitated law recently passed, extending the term of military service from two to three years. This is the most discussed subject in France just now and has been the cause of many working-class demonstrations. This shout is also forbidden in the streets of Paris, but in this case the police were helpless. One young workingman just in front of me, dressed in baggy, green corduroy trousers, red sash, yellow shirt and gray cap- the French workingman is much more picturesque in his attire than our own was especially strident in his cry of “Les trois ans,” and, judging by the way the police looked at him, I am sure they would cheerfully have taken him.

Around me everyone wore a little red flower in his buttonhole and copies of L’ humanite the Socialist organ, and La Bataille Syndicaliste organ of the unions, were frequently consulted.

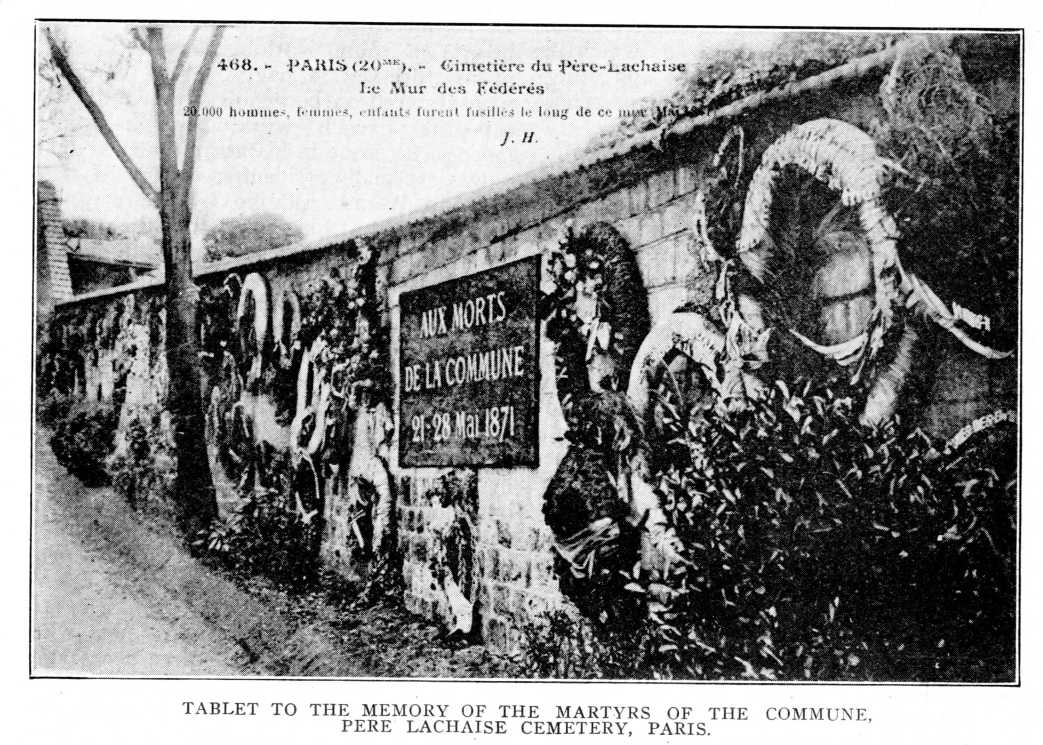

We now took a turn and started downhill. The crowd suddenly became silent and uncovered their heads. Around a wall in front of us the police were massed in battalions. A section of the wall was covered with fresh wreaths. In the center was a plain tablet inscribed: “Aux Morts de la Commune (To the Slain of the Commune), 21-28 Mai 1871.”

Here the workingmen and women, who took charge of Paris forty-three years ago and ran it peacefully and well, were lined up, after being driven from barricade to barricade, and mowed down by machine guns, their bodies piling in heaps against the wall. From 20,000 to 30,000 men, women and children were shot down in the seven days of terror.

I paused a moment for a look up and down the wall, whereupon came the warning voice of a cop: “A vancez ca, monsieur’. (Move on, mister).

So I advanced with the crowd, as silent now as it previously had been noisy. As I walked toward the exit of the cemetery, I noticed that the grounds around the Commune wall, though crowded with tombs elsewhere, were unoccupied save by grass and weeds. I learned afterward that the French respectables do not wish to be buried near the Communards. Thus does class division extend even beyond the border line of life.

Though there are countless monuments, pictures and what-not celebrating every other phase of French history, I found no memorials to the Commune, save this, in Paris. But I learned that the spirit of the Commune still lives in the hearts of its working people.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n02-aug-1914-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf