John Reed visits the arms plants of the Petersburg suburb of Sestroretzk during the Revolution as the workers, including some ‘Americans,’ take over management of the factories and supply guns to the Red Guards.

‘Factory Control in Russia’ by John Reed from Voice of Labor. Vol. 1 No. 6. November 1, 1919.

SESTRORETZK lies about half an hour by train from Petrograd, on the Gulf of Finland. All the guide-books of before the war describe it as a fashionable summer resort for the leisure class of the capital, the same sort of place as Long Beach is for the leisure class of New York. After describing this part of it, the guide-book may mention casually that there is also located the Sestroretzk Arms Factory, where guns were made for the armies of the Tzar, and which was founded by Peter the Great in 1714.

After the Revolution, however, the “summer-resort” receded into the background, and Sestroretzk became noted for the Arms Factory — that is to say, the workers in the Arms Factory.

I visited Sestroretzk about the middle of October, 1917, while the Kerensky Government was still in power. Already, however, the revolutionary transformation in the factory was far advanced. This was true of all the government factories — for Sestroretzk was a government works. The reason for this was very simple. The Government factories were administered by appointees of the Tzar’s Court — usually incompetent old army officers with a pull, who, being without any personal responsibility and without any “stake” in the business used it merely as a sort of graft. Moreover, the Government factories were militarized and the commanding officer had the power of life and death over the men, while he exercised with ruthless brutality. Workers who didn’t submit were immediately drafted into the army and sent to the front. Men who went on strike were court-martial led and some of them sent to Siberia. Labor organizations, of course, were strictly prohibited. Then came the Revolution of March, 191 7. With the fall of the Tzar, his direct appointees in control of the Government factories also fell. The worst tyrannical officials ran away. The long-suffering workers arose and killed the most brutal, beat others and arrested the rest. The management of the Government factories collapsed with the Government, and the workers, faced with the prospect of closing down the works, were forced to try and keep them going.

Sestroretzk Leads

Sestroretzk, the largest and most important of the four Government factories, employing 8,000 men, took the lead.

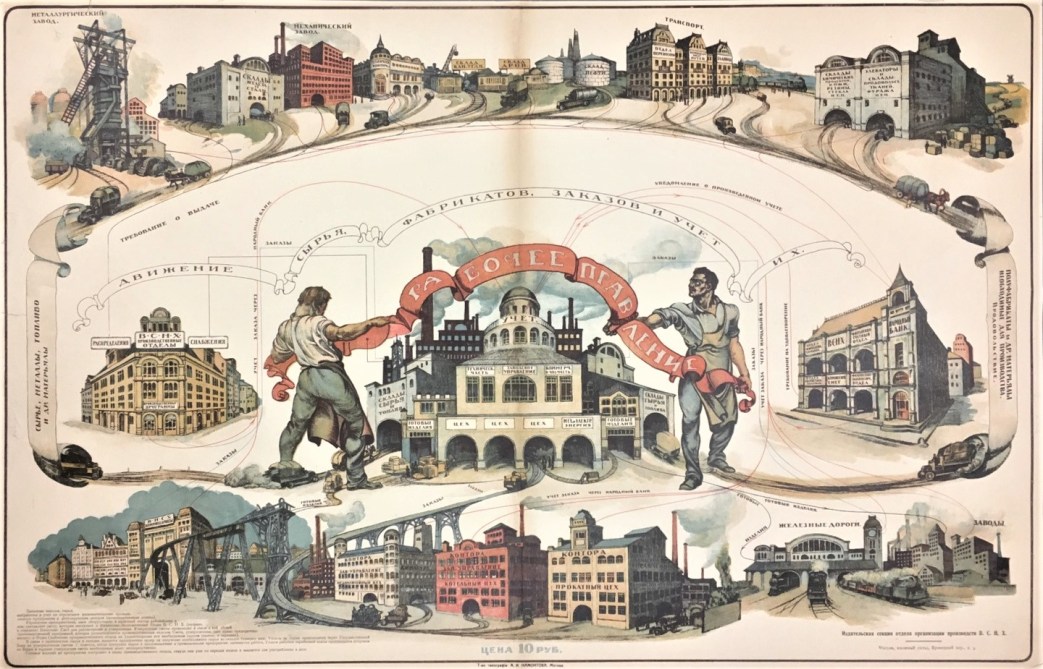

A committee composed of delegates from each department of the works held a meeting. This was the beginning of the vast network of Factory Shop Committees which afterwards spread over all Russian industry. This committee called a conference, first of the gun works, and then later of all the Government factories, in April, 1917.

The conditions in these Government munitions plants were extraordinary. In the first place, the new Provisional Government had inherited all the vast of the Tzardom. It was hopelessly involved in political complications and in reorganizing the army at the front. For several months there was no time to interfere in the operation of the munition plants, which were, moreover, delivering regularly their quota of war-materials.

Unlike the private factories, which depended upon the regular machinery of business, and where the owner was always on the job, the Government plants had certain fixed orders to fill, and the workers had a wonderful opportunity to make experiments in industrial control without official interference. And so, when finally the Kerensky Government turned its attention to Sestroretzk, workers control was too firmly established to be upset, no matter how hard the Government tried.

What Had Been Done

When I was in Sestroretzk, it was the model factory of the Petrograd District, and well illustrated the constructive and creative powers of the Proletarian Dictatorship. Hours of work had been reduced to to 8; Wages raised 45 per cent ; Production had been increased 20 per cent; the cost of operation had been about cut in half.

The Factory Shop Committee was practically in complete control. All the former administrators had run away, or been fired, except three technicians Konovalov, the chief engineer, brother of the Minister of Commerce and Industry in the Kerensky Government, by the way — was told to leave on the day I went through the plant. He had attempted to restore the old insulting discipline in the factory.

Two great additional buildings had been begun by the Tzar’s Government in 1914, and still loomed unfinished, a monument of graft and waste. The committee discovered that dishonest contractors had put into it rotten concrete and flawed steel. The committee fired the contractors, mobilized the factory hands and completed the two buildings in three months at cost, using the best materials.

Formerly there had been a tiny military hospital in the place, for soldiers only, with five beds and one doctor. The committee built a new brick hospital open to all workers, with seventy-five beds, three doctors, a nurse and a dentist. Formerly the Government had allowed 6,000 rubles a year for this work. Now it cost 15,000 a month. The Kerensky Government squealed, but it had to pay. Formerly a sick workman got half pay, now he received his full wages. One per cent of every worker’s wages went to support the hospital. Although Sestroretzk had existed for three centuries, there never had been a sewer system in the town. The cost of emptying cesspools of the factory and houses of the officials alone had cost 27,000 rubles a year. The committee had installed a permanent new system of sewage filtration at a cost of 67000 rubles, whose operation cost about 2000 a year.

When the coal supply ran low, the Committee sent a delegate all the way to Don Basin to get some, which, he did by negotiation with coal-miners’ and railroad men’s unions.

The committee then went into the business of supplying the workers’ needs. This was necessary because of the complete breakdown of transportation and distribution facilities all over the country, which raised over the cities the continual threat of famine. The committee bought an old mill, got some secondhand milling machinery in Petrograd, and began to make flour. Meat, cabbage and other necessities were bought by travelling delegates and sent to Sestroretzk by car-loads. 2,000,000 rubles was raised by the committee and sent to England to purchase clothes and shoes for the workers.

Discipline

The committee had absolute control over the hiring and firing of all workers. Through it the workers controlled also the election of all technicians and members of the administration.

Formerly many wealthy and noble young men had escaped military service by getting a fake “job” through “influence,” in the factory. These loafers were immediately cleared out by the committee and then forced to go into the army. Moreover, the widespread unemployment forced the committee to take stringent measures so that nobody not absolutely dependent on his wages should take the place of a worker. If it was discovered that any man in the factory owned more than 15 dessiatines of land, or received any other income, he was fired.

The day I was in Sestroretzk a great factory meeting was held after working hours, which voted unanimously a resolution against Drunkenness — a weakness for which Sestroretzk had always been noted. In part, the resolution said, “We are not puritans, we do not wish to interfere with a man’s personal liberty, but the Revolution demands clear brains and iron wills, which are obscured and weakened by liquor. Moreover, a drunken man is a disgrace to a free people. Comrades, if you must get drunk do so in the privacy of your own homes. If you meet a drunken man in a public place, lead him home to his wife.

Town Politics

Before the organization of the District Soviet of Workers and Soldiers, the Factory Shop Committee had been the supreme ruling body, not only of the workers, but also of the town. This was perfectly natural since in winter the town lived by and for the factory. In those days even divorces were granted by the committee. Later, however, with the organization of the Soviets in Petrograd, Sestroretzk, in common with all other places within a radius of 50 versts from Petrograd, organized a District Soviet, which had its delegates in the Petrograd body.

A Bolshevik secret branch had existed in the Arms Factory even under the Tzar. After the Revolution the great mass of the workers were consistently and violently Bolshevik.

When the District Soviet was organized, although the workers were in the vast majority, they did not at that time insist upon Proletarian Dictatorship. All parties and classes were admitted to the town government.

A central council of 50 was elected, and the council in turn elected an executive committee of 3, who managed the town organization. These 3 were paid a salary of 500 rubles a month. (In other townships it was 100-150.) The committee of 3 appointed committees on Housing, Food, Finance, Land, Schools and Education, Labor, Sanitation, Taxes, Statistics and Highways.

When I was in Sestroretzk the council of 50 was composed of 25 Bolsheviks, 4 Mensheviks, 8 Socialist Revolutionaries, 4 Cadets, 8 landowning peasants representing village communities and 1 Jew.

Formerly, the President of the Local Zemstvo was appointed by the Nobles, Assembly of the District, cooperating with land-owners. Now he was elected by universal suffrage. One Judge was elected by the Zemstvo — two by the Soviet.

Americans Prominent

Three “Americans” were the leaders in Sestroretzk, and it was due to their organizing genius and their experience in American industrial processes which was responsible for the miracles achieved at Sestroretzk. It can truly be said that the Factory Shop Committee system was originated by them.

First and foremost was Sam Boska, once walking delegate of the Carpenter’s Union No. 1001 in New York, now member of the Central Executive Committee of All Russian Soviets.

Manyinin, once well-known in New York, where he was head of a Russian Co-operative Machine Shop at 176 Worth Street, now Mayor of Sestroretzk.

Zorine, who was in New York with Trotzky. Chairman of the Bolshevik faction. Zorine later became special representative of the Committee for the Fight Against Counter-Revolution.

It was the Sestroretzk factory which delivered arms to the Red Guard of Petrograd upon Trotzky’s orders — thus first arming the Red Guard. It was Sestroretzk which sent a guard of workers from the North when Kornilov came.

The Voice of Labor was started by John Reed and Ben Gitlow after the left Louis Fraina’s Revolutionary Age in the Summer of 1919 over disagreements over when to found, and the clandestine nature of, the new Communist Party. Reed and Gitlow formed the Labor Committee of the National Left Wing to intervene in the Socialist Party’s convention, eventually forming the Communist Labor Party, while Fraina became the first Chair of the Communist Party of America. The Voice of Labor’s intent was to intervene in the debate within the Socialist Party begun in the war and accelerated by the Bolshevik Revolution. The Voice of Labor became, for a time, the paper of the CLP. The VOL ran for about a year until July, 1920.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/v1n6-nov-01-1919-voice-of-labor-opt/v1n6-nov-01-1919-voice-of-labor-opt.pdf