Robert Minor went to the mining area around Wilkes-barre, Pennsylvania to investigate conditions for the REVIEW and sent back this evocative report, complemented by his marvelous sketches of the area.

‘In the Anthracite Hills’ by Robert Minor from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 16 No. 10. April, 1916.

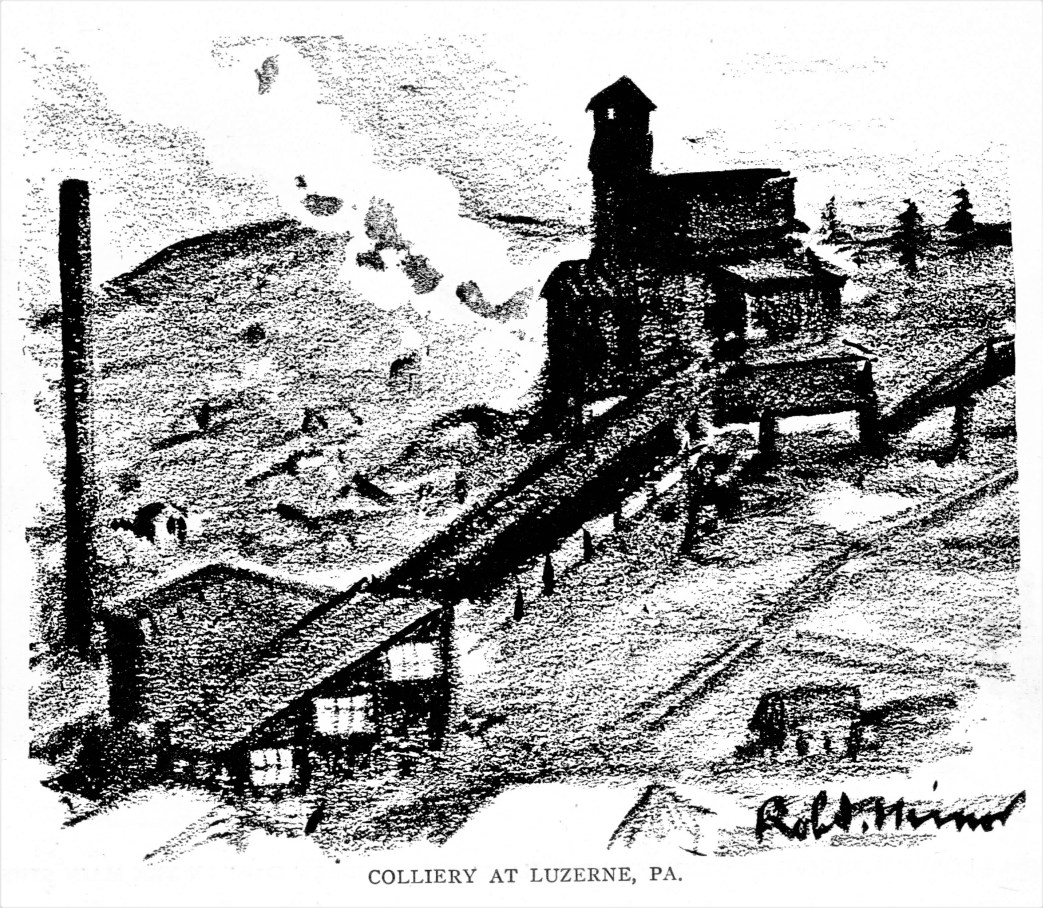

BEFORE starting for the anthracite coal fields to investigate and picture for the REVIEW such conditions as might account for a threatened strike of tremendous size, I cast about New York City for a “tip.”

‘WHY, THEY HAVE PIANOS IN THEIR HOUSES!” exclaimed one wealthy coal stockholder. They imagine that big war profits are accruing and they greedily snatch for a part. They are making a good living and more; now they want money to blow in on luxuries.”

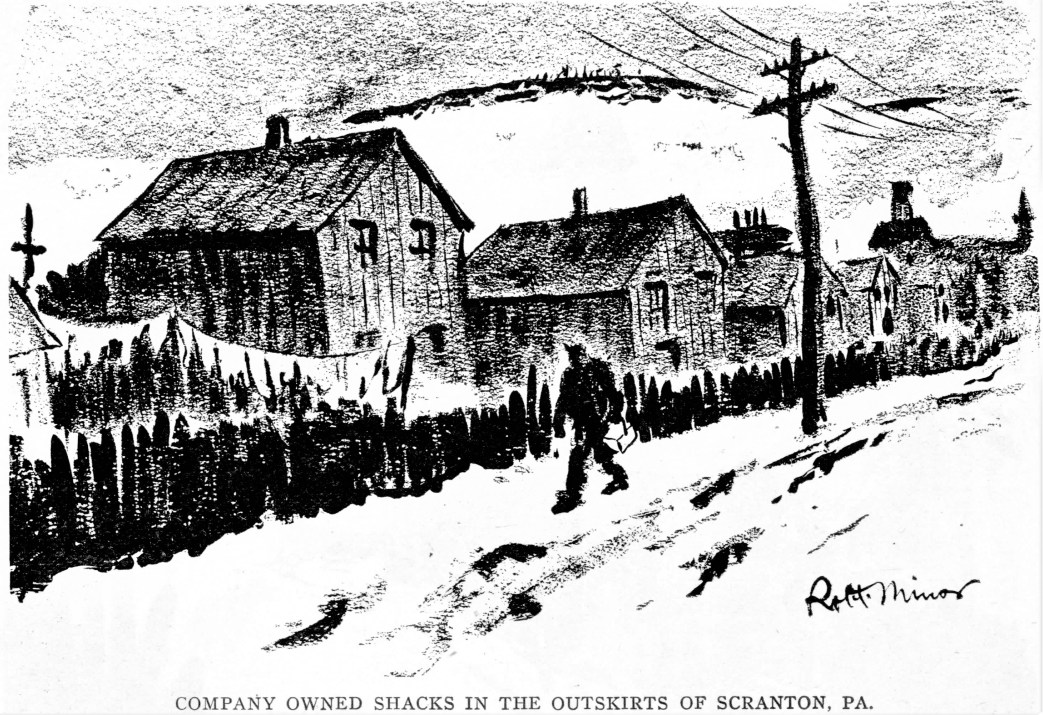

In the outskirts of Scranton lies the little mining settlement of Underwood. Winning the confidence of a mine mule driver, I went to visit some miners under his guidance.

The first home I entered was that of a Pole, living in a company house.

“Have you a piano?” I asked. He looked at me quizzically.

“This ain’t no place to keep a piano,” he said, pointing to the front door, where a split up the middle admitted both daylight and whistling wind.

It was cold inside. The back door was a barn door, so crudely hanging in its place as to show a bit of landscape thru the crack.

The house is built of one thickness of lumber with a little plaster inside.

The miner explained that he papered the house and partly floored it himself, the place as turned over to the renter by the company having the bare earth for a portion of its floor.

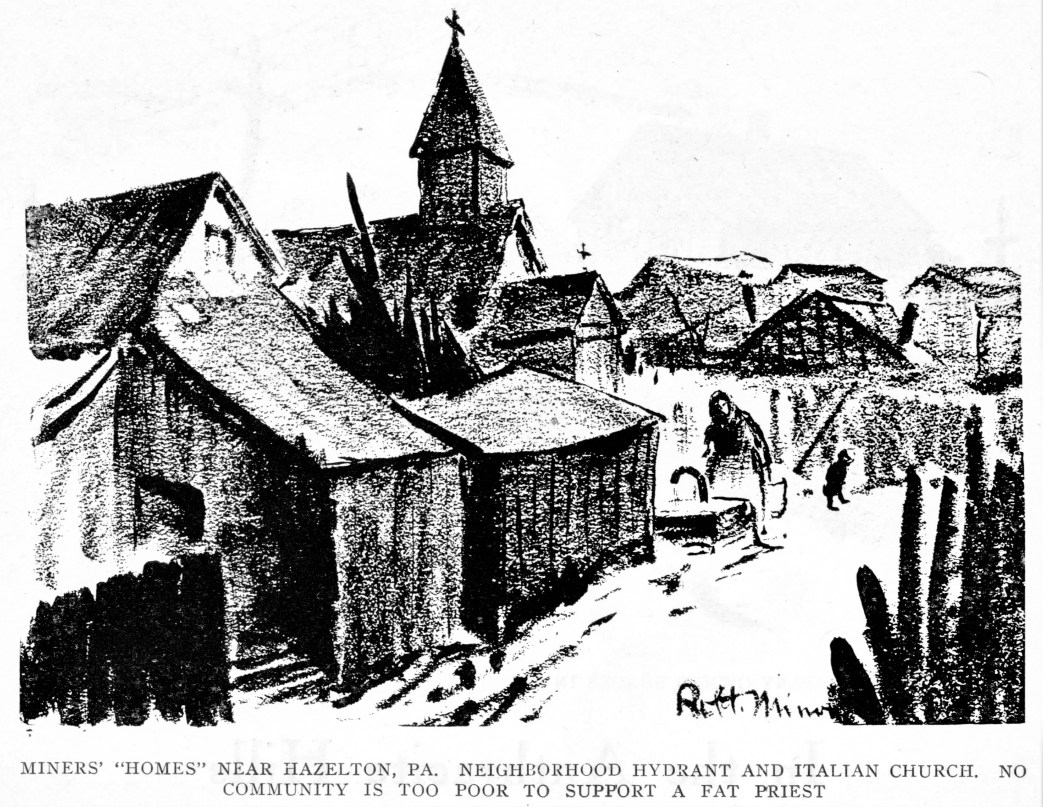

These company houses – each four rooms and a lean-to- are built in a dismal row, all exactly alike. Asked where his water supply was, the miner opened the door and pointed down the hill to a pump.

“That is the water supply for eight houses,” he said.

Sewage systems are unheard of. The vast majority of the houses would just about do for barns. They are not rented to “laborers,” as “laborers” (miners’ assistants) are not able to pay the rent.

When the union itself tried to get the Underwood miners to wait, they threw down their tools, left the old union, and called upon Joseph J. Ettor of the I.W.W. to organize them.

So, it isn’t a desire for “pianos and such” that causes the trouble in the coal fields.

But, as one Irish miner said to me, “Ain’t a miner got a right to a piano?”

It is well worth noting that the I.W.W. is organizing in unorganized towns, often where the workers permitted the old union to expire because of their lack of faith in its ability to accomplish anything for them. Since August, 1915, the I.W.W. has kept organizers and speakers in the Scranton district. The results were shown in the first I.W.W. convention at Old Forge, on Sunday, Feb. 6. Ten towns and twelve locals and branches were represented by 46 delegates.

The strike thruout this section has been on for over four weeks. The coal barons at Durrea, Dupont and Old Forge have thrown up the sponge, settled with the I.W.W. and the miners are back again on the job. At Greenwood there are several hundred still out. The spirit of solidarity among the Polish and Italian miners is splendid. About one hundred men have gone back into the mines under the protection of deputies, but there were very few miners among these scabs.

In a report of the Greenwood strike, the Scranton Times of Friday, Feb. 25, prints the following:

“There is a very peculiar situation in Greenwood, as shown by the· duebills of the striking miners, most of their laborers receiving more money.”

A duebill, it may be explained, is a bill to the miner, showing amounts due to him after the company has deducted all the charges against his earnings.

“The laborers won’t work for less than two dollars a day, and miners who showed duebills at the meeting yesterday had anywhere from 31 cents to $19.38 coming to them.

Anthony Petrosky, who is number 159 on the company’s roll, worked eight days. He was out of the mines several days because of the death of a child at his home. It was the intention of Petrosky to pay something on the funeral account when he received his wages. His duebill showed him entitled to $2.51 for the eight days. He told his story at the meeting yesterday.

“Ludwig Cling was another to tell his story during the session. There are seven in his family, and he has been mining for some time. His number is 160. His earnings for two weeks amounted to $24.31. The deductions included three kegs of powder, cost of sharpening tools, ton of coal, and $14, which was paid his laborer. His balance was 31 cents.

“Some of the duebills shown at the meeting yesterday follow, most of them being for two weeks’ work:

“Miner No. 157 earned $7.67, and the deductions were $7.75, leaving him in debt 8 cents to the company.

“Miner No. 159 worked eight days and received $2.51, and one ton of coal. Claims to have been cheated out of $17.91. Same miner for a previous two weeks received 8 cents.

“Miner No. 518 worked nine days, got out ten cars of coal and earned $38.51. The deductions were $40.49, and his net earnings were $8.02. His laborer received $14.”

Under the company store system, a very close imitation of chattel slavery was shrewdly maintained. A trip thru the anthracite hills brings one into contact with men who, in the old days, worked years for coal companies without once receiving a piece of actual money-always in debt to the company without hope of release or even the power to rebel. They simply were doled out what a black slave received before the civil war-their board and clothes.

The strike of 1900 swept that form of slavery away- ALMOST. It still persists in the Scranton region among the smaller coal companies.

The regulations abolishing the system are now evaded by the simple means of putting those miners who do not trade at the company store to work in places where they cannot get out enough clean coal to make a living. Of course, the miners are “free” to trade where they please.

But why do the miners want more money? Strikes of the past have raised their pay about 26 per cent.

Inquiry brings out that the cost of household supplies in the region have increased in the same time between 40 and 50 per cent. Rents have gone up 40 per cent in Scranton in the past 15 years, according to the miners’ figures, and they say the companies charge employes 75 per cent more for their household coal.

It is easy to see where the 26 per cent wage increase goes.

Mine jargon divides the miners into two classes- “pets” and “suckers.”

The “pets”- who, the miners claim, are chosen for their loyalty to the union get jobs at “robbing pillars,” which means tearing out the solid masses of coal which are left standing till the last to hold up the roof. This enables the favored one to make $75 or $80 in two weeks.

“I want to fight!”

This is the answer I got from a hard coal miner to my question as to living conditions in the anthracite fields of Pennsylvania. This man has been working near Wilkesbarre and living in a company house 18 years. He has four children.

“What do you want to fight about?” I asked.

“For straight pay for every pound of coal I cut, instead of being docked a quarter or a half-car for a few fragments of rock in the coal.”

The man who said he wanted to fight was in a saloon, drinking beer. I wondered whether to take him seriously. Then he invited me to his house; After ten minutes in that windy shack, let to him by his employers, I wondered why he didn’t spend ALL his time in the saloon! He was a very sober fellow.

The liquor question is made much of in that district. Some of the miners’ union organizers told me a crusade against alcohol is strongly backed by mine operators every time there is a threat of labor troubles.

“It’s to give the men something to blame instead of the boss,” said one. “The operators pick any movement that has a respectable look and back it up, trying to make the miners place their hopes there instead of in the union.

“Right now there is an evangelist going at it hammer and tongs, diverting the men’s minds from the impending strike.”

“What makes you think it has anything to do with the proposed mine trouble?” I asked.

“Because all the coal operators are footing the bills for the revivals.”

The whole of life there seems to center around coal. Even the medical profession is not untouched. The compensation law of Pennsylvania requires the companies to pay the medical expenses of an injured miner to the extent of $25. or for a major surgical operation, $75.

The miner is to receive 50 per cent of his wages for the time he is incapacitated after the first 14 days.

Well, the companies hire the doctors, many of whom, the miners say, are so solicitous of their employers’ interests as to declare the injured men capable of working at the end of the first 14 days, so he receives nothing.

But why are not these difficulties attended to by the conciliation board appointed for that purpose? They are- IN THE COURSE OF TIME. That is, a miner complains of injustice of treatment or unfair discharge and waits for a decision several months. When the decision finally comes, even tho it may declare him in the right, the miner generally receives no compensation for time lost.

It seems as tho all the machinery of law and agreement, built to protect the coal miners, either clogs or breaks down. He clings to the last reliance in which he has hope-the union.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v16n10-apr-1916-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf