Both a history of the art, and a critique of its tendencies, an article from Lincoln Kristein, co-founder of the New York City Ballet, on the fascinating world of ‘revolutionary ballet.’

‘Revolutionary Ballet Forms’ by Lincoln Kirstein from The New Theatre. Vol. 1 No. 9. October, 1934.

USED in connection with a spectacle, “ballet” has hitherto meant a series of theatrical dances more or less closely connected by pantomime based upon a story slight enough to be a pretext for the presence of a troupe of dancers, but in no way to interfere with the technical display involved. There have been notable exceptions to this, but only as exceptions. Used in connection with the vocabulary of the dance, “ballet” means a grammar of gesture and movement based on five positions of hands and feet, originating in Italy, spreading to France, flowering in Russia. In the course of its four hundred year history it has absorbed from its successive homes local, national and social dances, occupational gestures and innovations from individuals all along the line. As differentiated from ritual, folk, or social dancing, it is preeminently theatrical. Its limits are imposed for the sake of greatest legibility to the greatest number of people seeing it.

The word “ballet” has enjoyed a wide unpopularity in America for the last ten years. Most of the work which could, with an indulgent stretch of the imagination, be called “ballet” here on view, was a dilute or corrupted form of the thing. “Ballet” meant girls in white tarletans derived from Degas or high class movie prologues. Recently when a popular ballet company displayed itself in New York, it aroused considerable intellectual distrust by its financial success, its opposition to the (to us) familiar exhibitions of our own “group” or “modern” dancers, and because few of its productions had anything more than a fragmentary or accidental interest. In spite of this, the word “ballet” is a good one and can still be used for the purposes of discussion.

The Ballet was preeminently a post Renaissance product. It flowered in the Baroque ornament of Versailles and not until the nineteenth century was it entirely divested of a verbal accompaniment, which final separation did much to accelerate its decline as a dramatic instrument. The grammar, the idiom of ballet developed independent of its uses. The forms and combinations of its steps in the ore, as it were, are one of the great contributions of western culture comparable to the use of polyphony in music, or aerial perspective in painting. Unfortunately the uses to which this language was put, to a far too large extent, were mainly rhetorical. Expressiveness was -sacrificed to brilliance, and difficult execution well achieved was canonized for its acrobatics. Ballet awaits a Don Giovanni, or a Hamlet. Its succession is so elusive, depending as it does on difficult systems of notation or human memory, that what seemed great tragedy to the balletomanes of 1850 seems preposterous to us, and we are perhaps inclined to underestimate the intensity of ballets like Giselle or Sleeping Beauty. Perhaps they provided a satisfaction equal to great tragedy. Gauthier and Poushkin thought so. But they have not survived for us, whatever the reason, like Mozart or Shakespeare. We still can be moved by individual dancers performing the. magnificent arias in movement, The Blue Bird variation, or the pas de quatre from Swan Lake; but these in fragments.

The best of ballet has come to us by way of Russia. Italy and France had their dominance, with the attendant glories of Sweden and Denmark. But Russia lavished her full attention and her imperial thoroughness on the western form, combined Italian acrobatics with French grace, and added an immortality of Slav consciousness and abandon. The Russian schools, state endowed, commanded the pick of European masters. The Russian theatres gave a possibility of perfection in production unknown anywhere else in the world. Their sense of the dramatic, of the word-made gesture plus the bodies moulded to elastic steel, make the names of Karsavina, Nijinsky and Pavlova living standards.

Yet before the war the Russian Ballet became international. After the Paris season of 1909, and the subsequent Diaghilev period, Russia was content merely to provide great dancers. The ideas, the direction, were still Russian, but the Russians of a cosmopolitan society, the Russian made a citizen of the world, or more accurately, a Parisian. In Russia the ballet schools were protected by the Revolution. Lunacharsky saw to that. Except in the winter, due to the lack of food and heat, the schools and theatres were continuously open. The Russians of today are probably the greatest technicians in the world. But the ballet productions in no way compare to the vitality of their cinema or dramatic theatre. The state of choreography in Russia today is not pre-war. It is late nineteenth century. The ballet is extremely popular in both the great State Theatres, but the popular successes are the same successes that delighted audiences of 1894, 1904 and 1914. This is no fault of the Revolution. The Diaghilev ballet carrying with it the greatest creative talent left Russia for good in 1911. What was left after the war, except for Gorski who in Moscow was the great composer of ballets and already an old man, and Golizovsky a real revolutionary, but a special case, was merely middle-aged memories of the stock repertory. Golizovsky is still in Moscow. But due to the extent of the general torpidity of choreography he seems an extremist. It is forgotten that already in 1910 he created innovations surpassing Wigman, and structurally far stronger than Duncan. Now he seems an eccentric. His Football Player was a notable success.

IN spite of this, the tone of Ballet in Western Europe has been predominantly Russian. The five choreographers of the International Diaghilev troupe were all trained in the Imperial School at Petrograd, with the exception of the last, who graduated from the State School of Leningrad. When Diaghilev died, his remnants and various brilliant White Russian children in Paris were formed into the Monte Carlo Ballet, which scored such a signal success in New York last season; and which now returns.

The Monte Carlo Ballet, creatively speaking, has little to recommend it, although as irrelevant amusement and delight for the sake of unique performers, it can be superb. The ballet dances are, largely speaking, from the Diaghilev Repertory (1909-1929). The few new ballets are an offshoot of his school: the ultimate of the snob Parisian chic of 1930-1933. Its future life is questionable. It has few lively sources from any field on which to draw. Its unscrupulous direction, its overworked dancers, its second-hand repertory and intense commercialism, and the lack of any youthful creative descent makes it an historic echo, but still an echo. It should be seen by all for reference and comparison.

It might be useful to review the great composers of theatrical dances during the last thirty years to determine the future direction of the medium. Michael Fokine as a young man literally revolutionized the principles of ballet when at the turn of the century, in a famous letter to the directors of the Imperial Theatres, he proposed reforms which have determined the whole direction of dancing and which we now accept as commonplaces. He precipitated a Romantic Revolution, drawing heavily on oriental exoticism, on Hellenistic Greece, on the great decadent Imperial periods for a decorative and violent subject matter. He also utilized a francophile story book version of Russia itself, and his immortal Petroushka is still danced in the Soviet Union, where it can be explained that the Charlatan . is the Imperial bureaucracy, the Moor is the old aristocracy, and Petroushka is the eternal, unconquerable soul of the common Russian man. And in every sense, Petroushka is a masterpiece, a milestone in the development of dance drama. Since the war, Fokine has lived in suspension in New York City. It is hard to believe that the composer of Fire Bird, of Daphnis, or Spectre, Igor, and Sylphides, is extant at the start of Riverside Drive. This summer, almost as an ironic spectre, his old successes triumphed again, at least from the point of view of big audiences. But there is little else left.

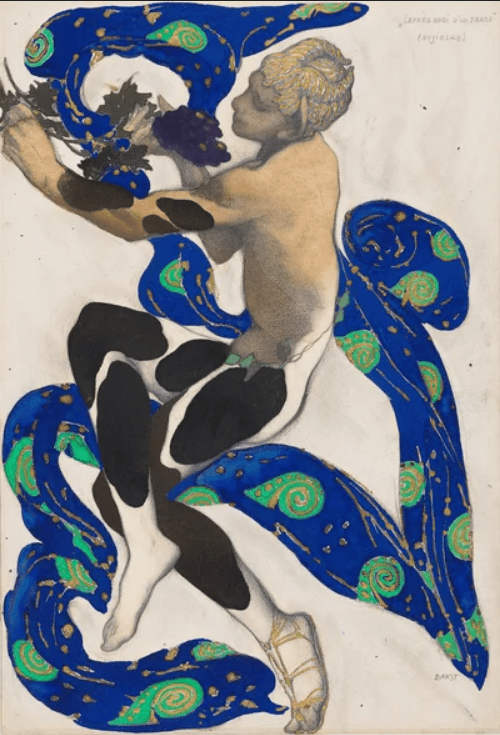

Nijinsky was the immediate and given cause of Fokine’s resignation from the Russian Ballet, and in spite of his tragic, unachieved career, it is difficult not to consider him as the single greatest genius of dancing in modern times. Superlative as a classic dancer, before he was twenty-five he reversed classic dancing and established a new species of synthesized movement which has been the virtual source of modernisms ever since. Nijinsky could not support dancing as mere divertissement or attractive amusement for its own sake. In Faun; he composed a complete lyric incident in fluid movement, at one blow destroying the atrophied idea of Greece as Phidian Greece, and with the recreation of the monumental archaic, suggested the creation of a simple, direct and profoundly felt modernism which was articulated in greater elaboration in the nationalist, pre-archeological Rites of Spring, and realized, in small, in Jeux- never to be realized largely in the unproduced but magnificently indicated formal dances for the music of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues. Nijinsky hoped for dancing as an expression of human action as intense and direct as possible; unhampered by a precedent, the legible objectification in terms of kinetic essences of the whole nature of human activity. Towards ritual, he proposed a mass dance drama, more important in scope and intention than any spectacle since the Greek ritual tragedy of the Bacchae. Nijinsky’s great contributions to dance-composition have not yet been realized, in the excess of emphasis on his own hideous personal disaster. Some inkling of his ideas may be gained from his wife’s biography, but only by inference.

LEONIDE MASSINE was. destined by a not very selective destiny to fill Niijnsky’s place as choreographer for the Russian ballet. The only one of its composers not to receive the benefit of the rigid discipline of the State School, his education was really based on the classic Spanish dance. The company found themselves in Spain for the duration of the war; Hence, one easily notices a preponderance of abrupt positions in his work, nervous and comic, stemming from the instruction of the great Felix, who grounded him in the initial Three Cornered Hat. Massine is an intellectual rather than a spontaneous or musical composer. His Skazki or Russian Fairy Stories are ingenious and charming, but the preponderance of his work has been a repetition of his early pantomimic dances, or lately, a visualization of the symphonies of Tchaikovsky or Brahms. This direction can hardly be considered fortunate. A competition is immediately set up with the music which is preeminently unsuitable for dancing. The greatest success possible is almost a literary tour de force. Very conscious of what is good theatre, he often misses what is good dancing, and is inclined to repeat a sure-fire hit until it misses. He has become the solitary composer of the Monte Carlo Company, and his creation is centrifugal. Fokine unkindly referred to his Brahms Choreartium as “Wigman sur les pointes.”

Bronia Nijinska, Vaslav’s sister, composed a few ballets for Diaghilev, notably the Village Wedding of Stravinsky and The House Party. Both stemmed strongly from Nijinsky. A fine dancer herself she has an unfortunate masculinity which, since she is not a man is often her undoing. Lately she has attempted a choreographic Hamlet.

Georges Balanchine was Diaghilev’s last composer. He is the son of the first musician of the Georgian Republic, Milaton Balanchivadze, who was signally honored this spring by a jubilee voted to him by the Soviet Union. Balanchine graduated from the State School in 1922. Under the strong influence of Kasian Golizovsky, he risked expulsion from the Academic Theatre by founding his own Young Ballet, among whose number were Tamara Geva and Alexandra Danilova, both now well known to New York. He was dissatisfied with the atrophy of the left-overs of the Imperial Theatres. Practising in a disused factory, he presented finally an evening of dancing, From Fokine to Balanchivadze: the history of contemporary dancing. He took a poem of Alexander Blok’s and in the forum of the deserted Dveranskyi Sobrani, the old House of Peers, his schoolmates danced the Blok verses while others recited them. It was the first step in an attempt to reintegrate dancing with the old, invaluable elements of poetry and music, the human voice and the melodic, instrumental line.

Balanchine served Diaghilev from 1924 to his death in 1929. It was the period of the disintegration of the ballet. The painters of the School of Paris were considered more important than either dancers or musicians. Novelty was at a premium. Titillation of the super-sophisticated worldly society of Paris and London was the single effect of these few years. Diaghilev himself seemed disinterested. Nevertheless, Balanchine produced ten ballets, two of unusual strength, Stravinsky’s Apollo, and the Prodigal Son, a drama of some religious feeling, based on episodes from a poem by Poushkin, with remarkable scenery by Rouault. On the one side Balanchine revived the crystal classicism of the pre-Fokine era, which he also had endangered in the recent insistence on the unsuspected. In the other he hinted at a curious sincerity, a desire to realize the full possibilities of dance drama.

Since 1929 his history has been vivid, from London, to Copenhagen, to Paris, to New York. At the age of thirty he is the head of the School of the American Ballet. Work done he finds is old as death. The direction of dancing is entirely ahead, and at a different angle from anything previously accomplished. Except-there was the Blok in 1922, and the Seven Capital Sins in 1933. Few people who saw it took the Seven Capital Sins at anything but its face value. Nevertheless this baffling work by two superb young German Communist artists, Bert Brecht, the poet, and Kurt Weill, the musician, was an important landmark in dancing history. On a hare stage, the classical ballet steps abandoned, under glaring lamps, with no scenic illusion, the chapters in the adventures of one girl in search of food for her family was intoned by her sister and double, Anna-Anna. As each sin was committed, another paper door was smashed. The music, acrid and tuneful, was the equivalent, but never the description of the dancing. An atmosphere of homely tension, desperation and personal anguish was invoked, in combination with the monotonous, aching familiarity of the melodies that was both uncomfortable and splendid. Balanchine left Europe, splitting with the Monte Carlo Company, of which he had been co-founder, because he considered their direction retrograde and retardative.

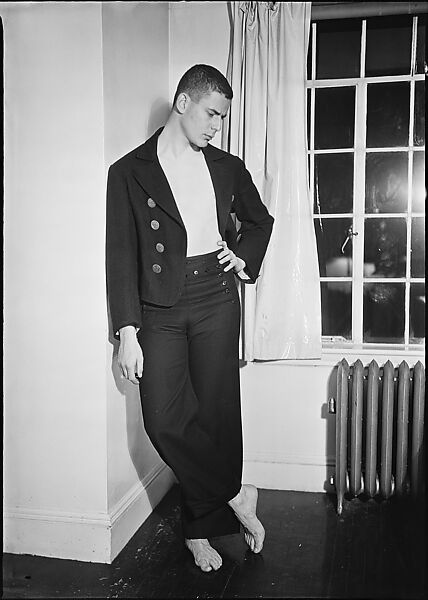

AT present the School of the American Ballet is in a state of gestation. It is attempting on the basis of the Russian State Schools, adapted to American needs, to create an excellent troupe of dancers. This takes time and patience. Balanchine luckily has both. But in the meanwhile he has experimented. He knows ballet as “ballet” is dead. The very word seems mortified. He has found an old word which may have a revivified meaning. Vigano, the Italian innovator of a century ago, composed ballets which he called Choreodrame: literally danced dramas. The idea of three ballet divertissements in an evening is through, however persistent. Ballet as innocent amusement is far too little to demand of it. Dancing can be the equivalent of any of the other lyric or dramatic forms. Words, spoken by dancers or by an independent choir in unison, without music or with it; the greater participation of the audience as a contributory factor in heightening the spectacular tension, the destruction of the proscenium arch as an obstructive fallacy, the use of negroes in conjunction with white dancers, the replacement of an audience of snobs by a wide popular support are all part of Balanchine’s articulate program. In the rehearsal classes at the School, these ideas are becoming crystallized and closer to production. In his first choreodrame, Tom, based on the Stowe novel of slavery in the South, E. K Cummings has heroically theatricalized that serious historic situation. The spectacle as realized will be more pantomime than dancing, more speech than song, more myth than ritual- but on its way to a closer realization of an enlarged drama, popular in its deep sense:

To understand ballet enough to be able to dance it requires at least a similar attitude of patience and application on the part of a student, as learning how to play the piano. It is a highly technical and specialized form. Its exercises provide equilibrium to the body under unusual circumstances, speed in transitions, a constant fluidity, a capacity for moving in and through the air. There are those who are more fitted to be dancers than others, and some people naturally have an instinctive talent for theatrical dancing. Due to the half-considered reforms by Isadora Duncan, where with her characteristic fine indignation she insisted that everyone could dance, and to the exceeding dilettantism fostered by the central European systems, many young people feel that all they need is the will to do it. In one sense, everyone can dance. Over the next ten or fifteen years an excellent weapon for social solidarity would be the revival or creation of group dances practiced only for fun at occasions when people meet. But these dances, dependent for their effect on a spontaneous ease and simplicity in execution, have nothing to do with theatrical dancing. One reason that dancing has not been taken seriously by the majority of people interested in films and the theatre is that the performances of “groups” or “concert soloists,” however intensely well-intentioned, seem thin and only in occasional spots impressive as display. The dance audience in New York and in America is potentially enormous. But they have learned over the last two years to demand a presupposed technique, as efficient as a good musician’s or a good actor’s.

Ballet is an amalgam. In its purity it is rigid, back-breaking and ridiculous. Even the standard of purity for our century, Fokine’s Sylphides, is a romantic pastiche, based on lithographs of the mid-nineteenth century, embroidered with all sorts of sudden invention. For every decade, ballet changes. Massine has taken much from Wigman’s arsenal. Balanchine’s plastic stems from Golizovsky. But the skeleton underneath is strong enough, flexible and resilient enough to support any addition. Naturally a school is as necessary for theatrical dancing in America as it is in Russia. More so, for hitherto we have had none. Just as there are civic symphony orchestras supported by subscription in many cities, with allied conservatories, so can we have ballet schools and companies. The racial amalgam of America provides wonderful material for dancers. Many unusual indigenous combinations can enrich the stream. As for subject matter- the woods are full of it.

THE school founded last year in New York is naturally experimental and in a large sense transitional. It is supported by a few individuals until a large group can be interested. It would be at the present moment disastrous to ally such an undertaking to government funds, even if some appropriation were conceivably handy. The school is occupied in constructing a technical apparatus which will not be the property of any one choreographer, Any instructed or even any convinced person may have a hand at employing the troupe when it reaches a decent stage of perfection. Classes will be given in composition to encourage as many choreographers -as can be developed. But ballet is primarily a form against self-expression. It is a controlled design by a designer who has immolated himself in the general pattern, thinking of himself only as each separate dancer in relation to every other dancer.

To consider ballet as necessarily always the toy of rich men or the private pleasure of czars is unwise. So, for some centuries, were orchestras and paintings. When a state is achieved that recognizes: its obligation to its members as something more than a stopgap distraction, American dancers can afford to learn at state-endowed schools, put riot till then.

The last paragraph of a suggestive article by Harry Elion in the September number of NEW THEATRE embodies a major fallacy:

“The workers’ dance took over a great deal of the bourgeois technique. In fact most of the leaders in the dance were trained to be bourgeois performers. The workers’ dance must free itself from this influence and create a dance form that is expressive of the workers’ needs. This form will come as a result of the revolutionary content, providing the dancers free themselves from the idea that all that has to be done is to give the bourgeois dance working class content.”

Somewhere Marx has said that revolutions are caused by the profoundest conservatives, those people who wish to conserve the best of those human properties which they have gained and which they are in extreme peril of losing. The government established by these revolutionaries, as in the case of the Soviet Union, is the most conservative, in the best sense, that exists in the world. The form of theatrical dancing, hitherto aristocratic and bourgeois, will change less than it will be amplified. Its most important part, its base, will not be discarded any more than Shostakovitch discarded the form of opera. The workers need a demonstrated subject matter, a dramatized, legible spectacle, far more than they need a new farm for its expression. A form is only a frame and a medium, call it feudal, bourgeois or proletarian. It will be a signal service to the revolution if choreographers can give working class content to the preceding form. If that is done, it will no longer be bourgeois but revolutionary.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n09-oct-1934-New-Theatre.pdf