The full text of Scott Nearing’s pamphlet providing a valuable history of what was, in many ways, a model of working class anti-imperialist struggle from a metropole, as the Communist Party of France led a campaign, through Committees of Action, in solidarity with the Riffians against their common enemy, the French ruling class. Nearing reproduces Doriot’s parliamentary interventions and the text of Communist flyers, as well as some fantastic editorial cartoons by of L’Humanité from the era.

‘Stopping a War: The Fight of the French Workers Against the Moroccan Campaign of 1925’ by Scott Nearing. Social Science Publishers, New York. 1926.

1. Another War!

French workers faced a new war in April, 1925. To be sure, it was not a first class war, but merely a military struggle with a handful of Moroccan tribesmen. Still, it was war, and the international celebrations on May Day broke in upon the French preparations for the Riff campaign.

When Northern Africa was divided among the European empires, the homeland of the Riff tribesmen fell within the Spanish “Zone.” The Spaniards are indifferent colonizers. The Riffians, who are sturdily independent, after some severe fighting administered a severe defeat to the Spanish troops.

Having won his struggle against his Spanish “neighbors” Abd-el-Krim was free, during the opening months of 1925, to turn his attention to the aggressive activities of the French forces under General Lyautey.

2. Big Business and the Riff Offensive

French big business, like big business in other capitalist empires, directs French foreign policy. The Riff is an interesting illustration of the workings of this general rule of modern statecraft. There too, the French bankers, the French Ministry, and the French General Staff have worked hand in hand.

The essential economic relations existing between French big business and the Riff were ably stated in the French Chamber of Deputies by Jacques Doriot, who has played so large a part in the stand of the French workers against the Riff War. He brought these facts to the attention of the French Deputies in his speech of February 4, 1925, — two months before the opening of the Riff War.

The Banque de Baris et des Bays-Bas is one of the most powerful commercial banking institutions in France. With its Standard Oil backing, it is able to exercise an immense influence over the industrial and political life of France. This bank controls ‘over half of the 483 million francs of French capital invested in Morocco.

The Banque de Baris controls the bulk of this capital directly. A small amount is handled through subsidiary companies.

Two of the directors on the Board of the State Bank of Morocco (one of them the managing director) are directors of the Banque de Paris, During recent years the average dividend on the Morocco State Bank Stock has been 20 per cent.

The Banque de Paris also controls the Commercial Bank of Morocco. Four of its directors sit on the Board of Directors of the Moroccan railroads. It holds interests in the Franco-Spanish Fez-Tangier Railroad and dominates such electrical companies as the Sociale General d’Energie Electrique, The Banque de Paris also controls the Moroccan breweries, the Maghreb Milling Company, which has a monopoly of the Moroccan flour trade, and the Municipal Slaughter House Company which controls the cattle market and has the concession for constructing slaughter houses, markets, etc. The Banque de Paris also has interests in three important land companies and in a number of construction companies. It is likewise interested in the Moroccan International Tobacco Company.

Besides these widely scattered business enterprises the Banque de Paris controls the Compagnie General du Maroc, whose chairman is also chairman of the Banque de Paris, The Compagnie General, with a capital of twenty million francs, engages in ‘‘all operations likely to favor the development of Morocco.’’

Altogether the Banque de Paris controls at least twenty-five companies in Morocco. Thus this financial organization is not only a power in French economic and political life. It is, to an even greater extent, a power in the economic and political life of Morocco.

Morocco has proved a lucrative field for French capital. At the moment, attention is centred on certain iron deposits which are presumably very rich. While these deposits have not yet been fully tested out, similar deposits in Algeria and Tunis produce ore containing 50 per cent of metal, and the iron mining companies in these two countries have been paying as high as 150 per cent in dividends.

Spain, defeated in her efforts to retain a foothold in Morocco, turned over her iron ore concessions to the Banque de Paris group of French business men. The military defeat of Spain meant the economic triumph of the Banque de Paris, provided the French army could do what the Spanish military forces had failed to do — subjugate the Riff.

This is the economic background of the Riff War. French business wanted to see Spain lose in her fight with Abd-el-Krim. That gave French business the mines. French business wants the Riff whipped into line. Otherwise the mines cannot be profitably worked.

3. Food for Cannon and Food for Thought

During the years that preceded 1914 millions of workers all over Europe had striven to prevent another war. One of the greatest leaders in this movement the Frenchman, Jean Jaures, gave his energy and finally his life in the struggle against war and militarism.

After four years of carnage, the reasons for anti-war activity were plainer than ever, and while it was true that many of the militants had died and many more had lost faith, among those who remained the hatred of war was stronger than ever. As for the masses, they were learning that if the workers were to prevent a repetition of the horror of 1914 they must be prepared to act in their own behalf.

France was one of the chief sufferers during the World War. With her million and three-quarters of soldiers killed on the field of battle, with her long lines of mutilated men, with her ruined cities, her desolated countryside and the intolerable burden of debt heaped upon the people as a result of the struggle, Frenchmen had good reason to know the costs of war.

Among the workers peace sentiment is always strong. They know from bitter experience that they must not only do the fighting at the front, but that at home, when the blood-letting is over, they and their descendants must pay for the war. To the intelligent worker in modern Europe war cannot be justified without a lot of explaining.

Home and country seemed to be threatened in 1914. The World War easily became a war of defence in the minds of French workers and peasants.

The Riff War of 1925 was clearly a war of aggression. The soil of France was neither invaded nor threatened by the Riffs. The Riff campaign was a part of the effort of French imperialism to extend its power over North Africa and particularly over the Riff minerals. The majority of French workers and peasants were not even remotely concerned in the outcome of such a conflict.

Had there been no working class press in France and no understanding of the sweep of modern historic forces these facts might never have reached the French masses. But the French workers had learned their lesson in the bitter days following 1914, and in 1917 the Russian Revolution had broken across the world.

4. What Could the Workers Do?

Hostilities began between the French and the Riffians during April, 1925. Officially the date is April 28, although there is some dispute concerning the exact day. On May Day, 1925, the French armies were again taking the field. France was at war.

There were many apologists for the Riff War. French journalists described it as an effort to maintain French “prestige” in North Africa. French politicians insisted that the unstable Painleve Ministry did not want the war but considered it an inevitable phase of French colonial policy. French militarists accepted the struggle as a welcome relief from the years of inaction that had followed the signing of the Armistice. To official France, a war was a war.

But to the French workers war meant higher prices, higher taxes, privation, suffering, death. Millions of them were ready to oppose the Moroccan campaign.

When the Riff War threatened, multitudes of French workers desired to prevent it. When it broke out they wished to stop it. They knew that the imperial government of France had forced the war and that the imperialists would not make peace until their economic objectives had been attained. They were equally certain that the League of Nations would do nothing to enforce peace. The unrebuked rape of Egypt by Great Britain during the preceding year was too fresh in their minds to allow them to have many illusions about the usefulness of the League in a war crisis forced by one of the League’s leading members.

If the Government would not stop the war, and if the League could not stop it, some new method must be found to meet the crisis. The leaders of progressive working class opinion in France decided that the only hope for effective opposition to the war lay in organized working class action. They therefore determined to oppose the war; to attack and expose the French ruling class during the war as war makers and war profiteers, and to make every effort to fraternize with their fellow workers in the ‘‘enemy country,” the Riff.

5. The Committee of Action

French working class groups opposed to the Riff campaign began their offensive by organizing the Central Committee of Action. Originally this Committee was composed of representatives from the General United Federation of Labor, from the Communist Party, from the Republican Association of Ex-soldiers, from the Communist Youth Movement, and from the Tenants’ League.

During the Labor Anti-war Congress held in Paris on July 4-5, 1925, under the auspices of the Committee of Action, the Committee was reorganized. Members were added representing the peasants, the colonials, the organizations of women, the General Federation of Labor, and the Socialist Party. In this form the Committee represents the nearest approach to a united front that the French workers have been able to establish since the war.

The Committee of Action has branches or sections in most of the principal industrial centres of France. There are local branches, district or regional branches, and departmental branches. Each time that a labor congress is held in a locality or in a department an effort is made to have it organize a local or departmental Committee of Action.

Behind the Committees of Action and affiliated with them, a movement is under way to organize a Committee of Proletarian Unity in each factory, shop, station, and mine. All workers who desire to establish proletarian unity are included in these Unity groups. No distinction is made regarding political beliefs. They are the product of a widespread desire to get the working class together.

The Central Committee of Action, to use the words of its Secretary, “is not an organization. It is a grouping together of organizations for common action. The Committee does not levy on affiliated organizations. It is supported by voluntary contributions. It is a united front for a specified object — the Moroccan War campaign.”

The Committee of Action was directed by the Paris Congress of July 4-5 to establish local bodies throughout France; to agitate for the organization of similar committees in England, Spain, and Italy; to issue a series of appeals to working women, to young workers, to soldiers, to sailors, to the middle class, to the peasants and to the colonial peoples. The Committee was also authorized to convoke another Congress whenever this might seem desirable.

Vigorous and straightforward pronouncements have been issued by the Committee of Action. Here for example, is a part of its appeal to colonial peoples:

‘‘Comrades of the Colonies! French capitalism, in order to increase its immense reservoir of human energy and in order better to exploit it, will, after it has conquered you, deprive you of all the political and economic rights enjoyed by its own working class, in order to deprive you of the means of defence.”

Then follow special paragraphs directed to the workers in Algiers, Tunis, Black Africa, Madagascar, the Antilles, and IndoChina. Another paragraph warns the colonial workers against race hatred which is used by the master class to keep the workers divided. The appeal concludes:

“Working comrades of the colonies —

“You must join hands with the French workers in order to combat the capitalist manoeuvres to divide us…You must join with the workers of France in order to stop the bloody imperialist expeditions like that which is now being directed against the valiant people of the Riff.

“Uphold the French workers. Sustain their Committee of Action against the Moroccan War. Join them in demanding peace with the Riff Republic and the evacuation of Morocco. Long live the liberation of oppressed peoples! Long live the brotherhood of races! Down with colonialism!”

Later in the campaign, when it had been decided to attempt a 24-hour general strike as a protest against the Moroccan War, the Committee of Action published a statement that read, in part: “The financial disaster, which will plunge the working classes into abject poverty is held back only by an understanding with the bankers, who, wishing the riches of the Riff, will sustain the Government while it continues the war.” Following this statement there is a list of the unions that have already agreed to participate in a general strike.

6. Propaganda in the Chamber of Deputies

The public struggle against the Riff War has been actively waged in the Chamber of Deputies. The extreme Left bloc and their supporters rose again and again to denounce the war, to explain the economic causes which lay behind it, and to demand an immediate peace with the Riff. On May 27, 28, and 29, Doriot, Cachin, and Berthon particularly distinguished themselves by the effectiveness with which they challenged the position of the Government.

An idea of the vigor with which the French Communist Deputies attacked the war makers may be gathered from the Journal Officiel, At the sitting of May 27, 1925, for instance, Doriot pointed out that Abd-el-Krim had been in Paris in 1923 buying arms. Berthon had met him in Paris at the time and at Doriot’s suggestion he stated the fact to the Chamber. He was able to give the names of those with whom Abd-el-Krim had dealt, of the bank that financed the transaction, and to refer to the text of the contract under which the arms were secured. These facts, Doriot said, showed that in 1923 French firms were supplying Abd-el-Krim with arms; that the French Government was aware of the facts; that Abd-el-Krim was permitted to come to Paris on a passport officially vised, and that all this was done with the full knowledge that the arms would be used against Spain. As a matter of fact, these arms were now being used against France.

Abd-el-Krim, Doriot continued, had been trying for two years to come to an understanding with France. He had been accused of aggression against France. Quite the contrary; he had made every effort to establish peaceful relations with the French Government. To these overtures the French Government had refused to listen. If it was possible to talk with Abd-el-Krim on the subject of munitions in 1923, why was it not possible to talk on the subject of peace in 1924?

There was a very good reason indeed for the difference between the two cases. That reason was the intervention of French high finance. They wanted to sell arms in 1923. They wanted to get possession of the Riff minerals in 1924.

7. Doriot Names the Causes of the War

Four reasons lay behind the French aggression against the Riff’ in 1924. Doriot specified them:

“1. A question of prestige. Marshal Lyautey has said that it was necessary to maintain our prestige by showing our power to Abd-el-Krim…

“2. We wished to get within our protectorate the rich tribes north of the Ouergha, including at least 40,000 persons, and line them up against the Riffs. We were trying to set up a conflict, on the frontier, between peaceful tribes…

“3. We wished to secure the fertile territories of this region in order to drive out the natives in a few years, or a few months, and turn their lands over to some of the big colonizing companies…

“4. The most criminal object of all — as clearly expressed in our press — was to deprive Abd-el-Krim of his food supply, and to bring about conditions of famine by this blockade.’’

Doriot then read from the Temps in order to establish his fourth point. There were objections and protests, but he insisted that the real cause of the Riff War was hunger resulting from the French blockade begun in 1924:

“You have spoken of Riff aggression. You should rather speak of a revolt of the tribes in the French Zone, backed up by the Riffs, whom you have tried to starve. The war is much less due to the action of the famished Riffs than to the action of those who have starved them. (Applause on the extreme left.)

“M. Chassaigne-Goyon. — Is such language permitted in the French Chamber.

“M. Desire Ferry. — You are defending the cause of Abdel-Krim.

“Doriot. — As for you, you are defending your friends of the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, who are making profits out of these doings. (Cries from the centre and the right.)

“M. Eire. — This speech was written in Moscow.

“Vaillant-Couturier. — There has not been a colonial expedition in the course of which the same means have not been employed.

“Doriot. — We must admit that it is the French Government and the Resident General who must shoulder the responsibility for the existence of these conditions…

“M. Eire. — You carry the responsibility of traitors!

“Doriot. — The opinion of the workers and the peasants will judge those who were not willing to discuss peace as responsible for the death of the soldiers who fall in Morocco. (Applause from the extreme left). The war is here as. a result of your policies…

“Already two war aims are clearly expressed in all the papers. The first is to destroy the independence of the Riff State.

“The example of this Moslem people which after Turkey, and with little means, has actually succeeded in revising the treaties of the imperialists is too dangerous for the imperialists to tolerate…

“That is one of the fundamental causes of your war.

“The second cause of the war is this: the Riff is rich. The mines furnish a tempting bait for our bankers. The Banque de Parts et des Pays-Bas is already involved all through Morocco.

“M. Louis Rollin. — You would prefer that it should be an English bank?…

“M. Ernest Outrey. — With what can we develop the colonies if not with capital? You would bring nothing but disorder. (Exclamations on the extreme left).

“Doriot. — There are, I repeat, three fundamental causes that take you into the Riff: one, a military cause;…one, a political cause, and finally an economic cause, much more important than the other two.

“The President of the Council, who is supported by a press which demands the punishment of the guilty and an exemplary treatment of the Riffs, might oppose his still-born pacifism to these manifestations. He exhibits it every Sunday in official ceremonies. (Applause from the extreme left.) But he will hardly have a chance to use it now as we are already engaged in negotiations with Spain for a joint offensive, and we shall doubtless decide to enter the Riff and pursue the Riffians to their homes.

“We shall see what the future will bring. In any case, you are accepting the tactics of the military supported by the bankers…

“M. Pierre-Etienne Flandin. — M. Doriot, do you also suggest the abandonment of Tunis?

“Doriot. — We want Tunis to belong to the Tunisians. We do not want Tunis to go to Italy or to France. (Applause on the extreme left.)

“M. Le Mire. — And France to the internationalists?

“M. Jacques Duboin. — France to the French, M. Doriot.

‘”Doriot. — Yes, France to the French, and not to American capitalists — Morgan and the others. (Applause on the extreme left.)”

8. International Complications

Doriot then pointed out the danger of a world war arising out of the struggle for North Africa. Italy was anxious. Spain was uneasy.

“Britain also is not welcoming your military activity with enthusiasm. When the English feel that the southern shore of the Strait of Gibraltar might fall into our hands, they will become anxious. What will you give them for their silence?…

“Do not forget also that by your action you are angering the whole Moslem world…Even as far as India a great movement to help the Riffians financially has been organized. In trying to increase your prestige in a little corner of Morocco you have shown your true face as the oppressors of 20 millions of Moslems, and raised the other Moslems against you. (Applause from the extreme left. Lively manifestations on many sides).

“The President. — These words are not admissible. France has never oppressed any people. (Loud applause.)

“M. Franklin-Bouillon. — This is abominable language.

“M. Barthelemy Robaglia. — You strike the French soldiers in the back.

“M. Franklin-Bouillon. — It is a shame!

“Numerous voices. — To the door!

“From the extreme left. — Down with war!

“Renaud Jean. — Those who carry on colonial expeditions are the assassins. (Applause from the extreme left. Protests from the other benches.)

“From various sides. — Censure him! Censure him!

“The President. — I have already protested, as was my duty, against the words which M. Doriot has spoken…

“Doriot. — You have spoken of the soldiers from our colonies who died for France during the war. We also have the right to speak of them. These soldiers came from distant places to fight for a cause which was not their own! (Applause from the extreme left. Lively protests from other benches.)

‘‘Doriot. — At the moment when I was interrupted I was about to say that at that time you made them promises of democratic reforms, — of the right to vote. (Applause on the extreme left.)

“M. Gaston Thompson. — No! No!

‘‘M. Edouard de Warren. — That is false!

“Doriot. — These promises, made to Algerians and Tunisians, are not being kept today. Movements of disillusionment and antagonism against you have sprung up in these countries. Very largely they are dissatisfied with your country…

“The President. — ^You should say ‘our’ country. (Applause.)

“Doriot. — They are dissatisfied with your country, governed by your class, and they are thinking of giving themselves a somewhat greater freedom than you are willing to allow them…This little people, which has long struggled to liberate itself from foreign domination, needs a breathing space. They are trying to organize their country…They have already begun.

“M. Pierre-Etienne Flandin. — Yes, with cannon.

“Doriot. — Cannon that you have sold them, perhaps. The Riffs are waiting for a moment of peace to recommence this work. They would gladly receive the news of peace negotiations…During twenty years Morocco has cost 12,000 lives, according to the official statement. The present war will devour thousands more…While soldiers die and the expropriated natives suffer, the bankers are making scandalous profits, and some dividends are up to 30 per cent!…”

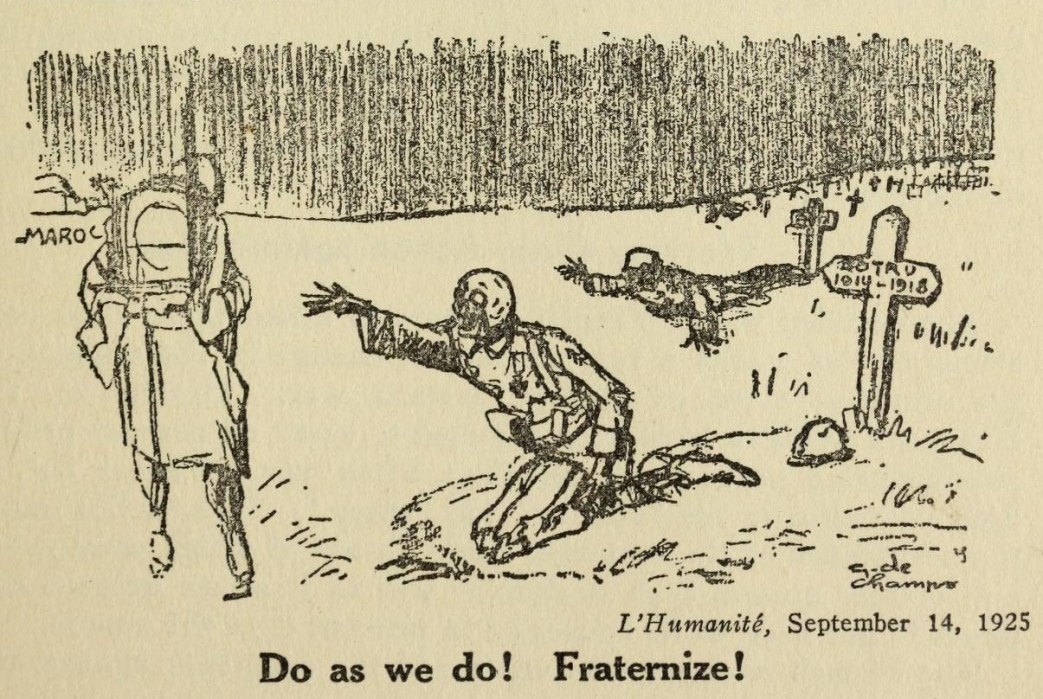

9. Doriot Tells the Soldiers to Fraternize

Doriot then read from the letters written by soldiers, expressing their dissatisfaction with the war, and demanding its termination. He was repeatedly interrupted and attacked during this portion of his speech.

“Doriot. — Tomorrow, gentlemen, when, leaving France with such a spirit of opposition, the soldiers reach the front and realize that in the interior of this country, workers and peasants like them want immediate peace with the Riff, and that those who govern France refuse to take the least step in this direction, they will consider themselves no longer bound to you. They will seek out the means to end the war that you wish to continue. They will remember that, in other circumstances, the marines on the Black Sea…(Applause from the left. Lively protests from other benches.)

‘‘M. Duboys-Fresney. — It is a call to mutiny.

*‘Doriot. — …as later on our soldiers in the Ruhr held out their hands to the workers who were opposing them. They will also remember that on this same Riff front the Spanish soldiers have talked with the Riffians. (Applause from the extreme left. Lively protests from numerous benches. Tumult.)

‘‘Numerous voices. — Censure!’’

After a period of disorder Doriot was again given the floor to make his position clear.

“Doriot. — Permit me then, so that there may be no misunderstanding…

“General Saint- Just. — The Government should jail you!

“The President. — M. Doriot, I ask you, have you invited our soldiers to desert?

“Doriot. — I said: Tomorrow, when they learn that in the interior of this country workers and peasants like them desire immediate peace with the Riff, and believe that it is possible to obtain this peace, and that the governors of France refuse to take the least step, they will consider themselves no longer bound to you. They will seek the means of stopping the war that you wish to continue. (Interruptions from various benches.)

“Let me read to the end, gentlemen.

“They will remember that, under other circumstances the marines on the Black Sea refused to fire on the revolutionary workers of Russia…that the soldiers of the Ruhr fraternized with the Germans. (Protests. Tumult.)

“M. Charles Francois. — It is not true!

“Doriot. — I say that the soldiers in the Ruhr fraternized with the German workers; that the Spanish soldiers on the same Riff front were not afraid to talk with the Riffians and I add: they will hold out a hand of friendship to those that you now call enemies. They will impose peace on you. That is my conviction and my belief. (Applause on the extreme left. Protests from other benches. Tumult.)

“From many benches. — Censure!

“Cornavin. — Down with war!

“Andre Fribourg. — You are bargaining with the blood of soldiers.

“The President. — I must say to M. Doriot, and to the Assembly, that these words are grave side by side with those already pronounced. If, unluckily, a soldier, in a careless moment was caught, lacking in military duty…

“Andre Berthon. — Make peace!

“The President. —…was caught under the conditions indicated by M. Doriot, he, Doriot, would suffer no ill effects; the poor soldier would risk his life.

“Prolonged tumult. The deputies on the extreme left rise and sing the International. Applause. Protests. The President puts to the Chamber the question of censure. Doriot is censured.

‘‘The President. — M. Doriot has the floor to finish his speech.

“Doriot. — Gentlemen, I finished my speech with my appeal to the soldiers. The appeal to fraternize was my last word.”

Other sessions of the Chamber during which the Communist Deputies spoke against the Riff War were no less tempestuous. Economic fact and political propaganda, clear-cut and unequivocal, was directed again and again at the French war makers and imperialists,

10. French Imperialism Gives Itself Away

Once in a long time the secrets which imperialists whisper in one another’s ears are shouted from the house-tops. This happened in 1917 when the Russian revolutionists published the secret treaties found in the files of the Tsarist Government. It happened again in June, 1925, when Doriot rose in the Chamber to read a letter written by M. Vatin-Perignon, chief of Marshal Lyautey’s personal staff at Fez, to M. Pierre Lyautey, nephew of the Marshal, living in Paris.

It was one thing to have a Communist Deputy describe the objects of the war and point out its causes. It was quite another to have these facts from the headquarters of the General in command on the Riff front.

The letter was dated May 25, 1925. It is reproduced in full in the Journal Officiel for June 23. The letter asserts that the French were not surprised by the Riff attack. On the contrary, “the Marshal was so well informed and had so thoroughly foreseen what was to happen, that, from January, 1924, on (see his reports to the government) he was preparing for war.” Marshal Lyautey had built a line of blockhouses north of the Ouergha. These blockhouses served the double purpose of excluding the Riffs from the rich Ouergha valley and of forcing the French prohibition against trade between the valley and the Riff. These blockhouses were constructed “in May, 1924, while Abdel-Krim, his attention taken up by the Spaniards, could not react…This front was established on a strategic Rise…without striking a blow. After May, 1924, this front was reinforced, fortified, and its communications with the base secured by a system of roads, bridges, and railways,”

The system of blockhouses, the letter explains, was intended to hold back the enemy until the arrival of reinforcements. “These reinforcements were arranged for and ready either in Algeria, or in France. That is a secret of general mobilisation which has not been and must not be revealed.”

The letter concludes with some comments on the difficulties which confront the French in view of the fact that the enemy territory, the Riff, lies within the Spanish zone.

“Either he will treat with us — but what will be the value of that for the future? Or he will continue to attack us, now on one point, now on another; which means a perpetual state of war. Or, in agreement with the other Powers, we can invade his territory, and that is a very big business (c est une tres grosse affaire.’)”

M. Vatin-Perignon concludes by stating that:

“The Marshal is entirely and fundamentally in agreement with the Government, and the latter is doing all that it can, all that it should. The duty of all good Frenchmen, who do not forget that our future in Morocco, that is to say, our future in the Mediterranean (Algeria, Tunis), is at stake, is to support the Government on this point with all their strength.”

The letter created a sensation. Its author immediately resigned as chief of Lyautey’s staff. No denial of its contents ever appeared and it has been generally accepted as a correct statement of French imperial policy in Morocco— a policy of deliberate aggression based on military conquest.

11. “Set Morocco Free!”

Again on June 23 Doriot, speaking in the Chamber, reiterated the position of the Communist Deputies. “If we were in power we would bring an immediate end to the French occupation of the colonies.” M. Renaudel interrupted with a question as to whether he had correctly heard. Doriot retorted: “We shall arrive at power by the revolution. It will be a proletarian dictatorship. We shall proclaim the independence of the colonies, Algeria, Madagascar, and all the colonies will have free choice as to their form of government.

Never was the issue made clearer. Never were there more emphatic and categorical statements concerning the right of self-determination for small peoples.

12. The Press Barrage

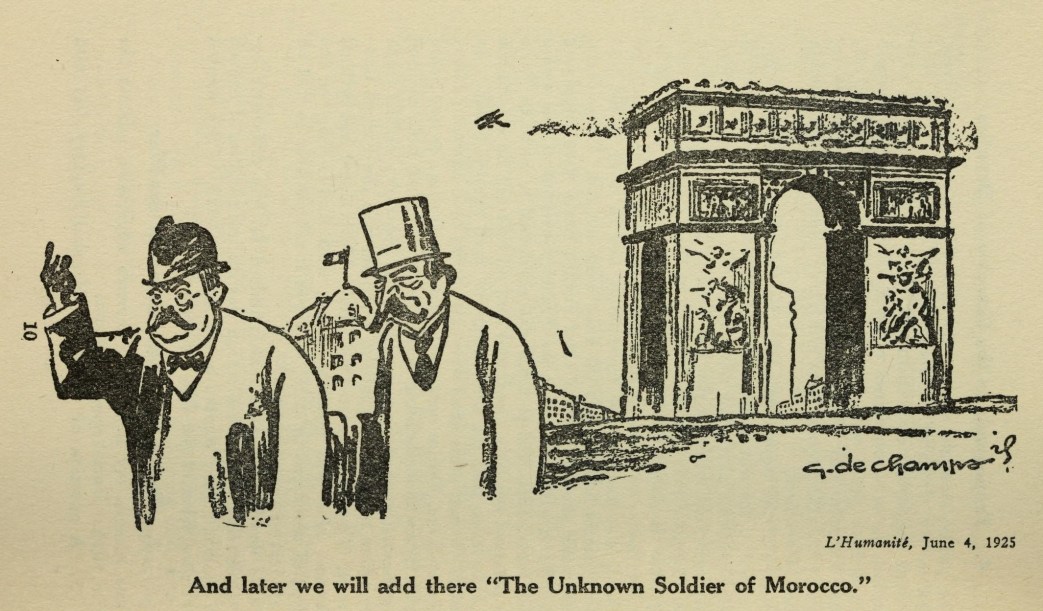

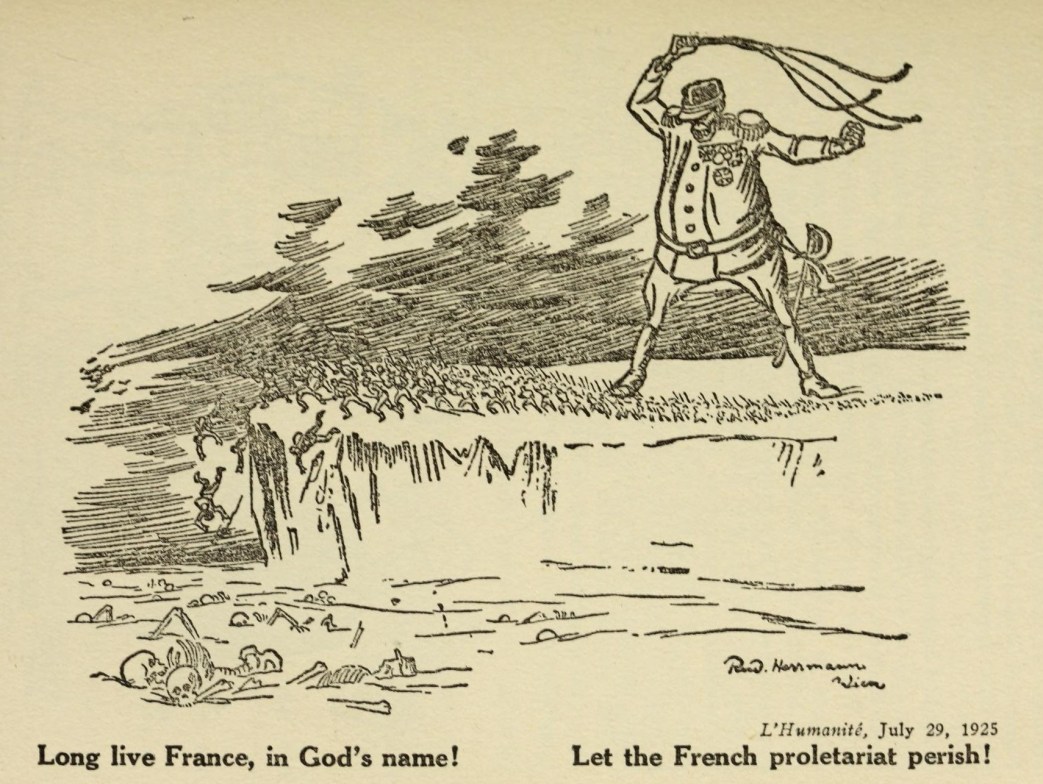

French radical journalism is always vigorous. The writers and cartoonists on L’Humanite and the other French papers engaged in the anti-war offensive have been at their best during their campaign against the Riff War.

Day after day L’Humanite has carried great streamers across the front page such as: “Immediate peace!’’ “Make peace with the Riff!” “The Moroccan menace! All together against the bankers’ war.” “The War for bankers’ profits.” “The Workers’ Congress against the Moroccan War — one sole remedy — working class unity!” “By order of high finance our soldiers must destroy a people fighting for its independence.”

The moral of all these headings is the same: a demand for the cessation of an imperialist war.

In the upper right hand corner of the front page of L’Humanite, where the New York Times ordinarily reports the weather, the editors ran a series of brief commentaries, challenges, and demands concerning the war. For example (July 25, 1925):

“Abd-el-Krim offers peace. Here is the reply of The New Age, official organ of the Left Wing: “Airplanes! Munitiensl” The next day, at the same point in the paper:

“The Government lied!

“It has always declared that Abd-el-Krim takes no prisoners.

“Now the Riff chief offers to return without ransom a third of the prisoners that he holds, both Spaniards and French.” Two days later (July 28):

“Twice, Abd-el-Krim, who is a ‘barbarian,’ has stated his peace terms.

“M. Painleve, ‘civilized,’ ‘democrat,’ ‘pacifist,’ is against secret diplomacy.

“But he has not once stated his terms of peace.”

These spectacular attacks on the Riff War have been accompanied by editorial comment, citations of military oppressions, stories of prosecutions of those guilty of agitation against the war, cartoons, calls for protest meetings, and letters from soldiers at the front. All this material has been courageous, straightforward and unflinching in its denunciation of the government and of the war.

The call for a meeting printed across the front page of L’Humanite for May 10 reads:

“People of Paris, the French imperialists have recommenced the Moroccan War.

“It will be long and bloody,

“Enough bloodletting! We must finish with this Moroccan nightmare!

“Comrade soldiers, fraternize with the Riffs.

“Workers of Paris, join with us in demanding immediate peace with the Riff and the evacuation of Morocco.”

Another call for a meeting printed on June 28 reads:

“Down with the Moroccan War!

“Socialist workers, see that you are represented at the Workers’ Congress on July 4 and 6.”

At a campaign meeting held by the Socialist Party, the secretary of the Sedan region presented to the workers of Vrigneaux-bois the following resolution which was unanimously passed and printed in L’Humanite July 24, 1925 : “The working men and women of Vrigne-aux-bois protest vigorously against the Moroccan War, and have decided to struggle by every means against the abominable butchery now in progress, to boycott the manufacture and the transport of arms and of munitions to Morocco, and to demand the immediate cessation of hostilities, the recognition of the Riff Republic, and the return of all our soldiers to France.”

13. A Frontal Attack on Imperialism

Throughout the anti-war campaign the editors of L’Humanite kept the economic aspects of the war in the foreground. On June 19 an appeal from the Communist International was printed, reviewing the economic and political situation with particular reference to the Riff War. On July 2 an appeal to French intellectuals signed by Henri Barbusse and a large number of fellow journalists denounced the war and called upon the French workers to enforce peace. On May 21, 1925, L’Humanite printed a story of the visit of Abd-el-Krim to Paris in the spring of 1923, giving names, dates, and other minute data connected with his purchasing of arms and ammunitions from French houses.

The workers are against all European imperialism,” declares L’Humanite in its issue of July 20, because “the defeat of French imperialism will signify the immediate cessation of hostilities and the saving of precious working class lives.” Therefore, “the French workers hope for and wish this defeat.

“Down with the criminal Moroccan War!

“Down with French imperialism!

“Peace without phrases!”

The Republican Association of Ex-soldiers (A.R.A.C.) issued a vigorous appeal which appeared in L’Humanite May 21:

“Ex-soldiers, victims of the war, up!

“There is no money to pay pensions to the victims of the war!

“There is money, on the other hand, to support the war in Morocco…

“The natural riches of the Riff are coveted by French imperialists.

“There lies the secret of the Moroccan expedition.”

14. Fraternize!

Doriot in the Chamber, L’Humanite and other papers. The Barracks, The Conscript, and The Advance Guard, circulated among the soldiers, handbills secretly and illegally distributed among the soldiers and sailors, placards posted in the barracks — all have advised the workers in the French army and nary to fraternize with the Riff. As the cartoonist Deschamps phrased it: ‘‘They force you to fraternize in death. Why not fraternize in life?”

At the beginning of the struggle L’Humanite published a front page appeal to the relatives and friends of soldiers, advising them that the Government was hiding the truth concerning the Riff War and that it was necessary for those interested in the soldiers to publish the truth, since the government would not even tell how many soldiers have been sent “to fight the war of the bankers.” “They pretend beside that the soldiers are happy to take part in this war for the profit of colonial freebooters, of parliamentary speculators and of the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, of which the sole object is to wipe out a free people in order to use their rich mines. But we know that the soldiers leave, shouting ‘Down with war! Peace with the Riffians!’”

The appeal concludes with the request that all letters and other information from soldiers be sent to L’Humanite, Large quantities of this material have since been published.

I5. Behind the Campaign — the Workers

Behind the anti-war campaign which has been prosecuted with such vigor are millions of French workers and peasants. Without this constituency the movement would have been crushed at its inception.

Before the Moroccan War began, French Communists had changed their form of organization from a political to an economic basis. Instead of being organized by districts they were organized by shops.

When it became apparent that the war would be of considerable duration two workers’ congresses were arranged, one for Paris and its environs, July 4 and 5, and one for Lille and the northern districts of France, July 12. Both congresses were notably successful. Both consisted of delegates elected directly from the shops and representing the wishes of a great body of French workers. The Paris Congress seated 2,470 delegates, representing approximately 1,210,000 workers. Among these delegates 195 represented General Confederation of Labor (Amsterdam) unions, 155 were members of the French Socialist Party, and 343 were non-party or independent. Throughout the sessions of the Congress, workers from shops, factories and offices rose to say simply and directly that what their fellow workers wanted was united labor action to smash the Moroccan War and to protect the standard of living of the French workers. Fraternal delegates from surrounding countries spoke to the Congress in the name of peace and unity. Liebaers, Secretary of the Belgian Garment Workers’ Union, concluded a carefully reasoned speech by saying:

‘‘Workers of France! You are faced with this alternative, from which there is no escape. You will either pay dearly for the error of your divided forces, and will allow still heavier chains of slavery to be riveted upon you. Or else, by Trade Union Unity, you will be able to stop the criminal war in Morocco, and then to forge the weapon which the workers need for their final emancipation.”

The Paris Congress issued a statement to the workers of the cities and country of France and of the colonies, in which it asserted that “a handful of bankers, masters of the earth, masters of all Moroccan production, wish at any price to extend their domination over the portion of territory that Abd-el-Krim and the Moroccans have liberated from the yoke of Spanish capitalists.

“The bankers wish to conquer the Riff mines.

“The bankers wish to destroy the Riff Republic because it has become for all oppressed colonial peoples a symbol of their independence.”

The Congress at Lille, one week later, was equally successful. There were 1,189 delegates representing 282,000 workers. As in the case of the Paris Conference these delegates spoke for the various Left Wing elements of French labor.

These Congresses have been described as the first Soviets of France. In one sense the description is correct. They represent neither political parties nor political ideas, but a new working class consciousness of power and responsibility,

16. The Imperialists Fight Back

This description of the valiant struggle which the French workers have organized against the Moroccan campaign has been written as though radicals in France were free to speak their minds and carry on their propaganda unhampered by government interference. The case is far otherwise. By June 18 L’Humanite was able to report 117 arrests with numerous prosecutions instituted against other comrades. These prosecutions had been instituted in cities as widely scattered as Paris, Toulouse, Nancy, Tours, Saint-Etienne, Calais, and Lyons. On July 26 L’Humanite reported three comrades imprisoned for two weeks as the result of the calling of a shop meeting.

“The Republic of bankers, bourgeois, liberals and Socialist leaders, accomplices in Moroccan propaganda, has nothing to learn from the monarchist regime of the middle ages. It allows the big legal thieves to run the roads and throws into its dungeons the sincere workers who are struggling against oppression.

“Since the 10th of July Comrades Raux, Le Troadec and Ringuit have been kept in absolute solitary confinement in the prison of Avesnes (Nord).”

Late in September, the Secretary of the Central Committee of Action estimated that there had been about 400 prosecutions and something over 100 convictions. Leaders in the big cities as well as more obscure workers had been prosecuted, but with this difference: the leaders were ordinarily given suspended sentences, while unknown workers in the smaller towns were sent to prison for as long as six months for posting up bills denouncing the war and advising the soldiers to fraternize with the Rifiians.

On Monday, October 12, 1925, the Central Committee of Action called a 24-hour general strike as a protest against the Moroccan War. The strike was particularly successful in Paris where it tied up the transport service and brought tens of thousands of workers to the streets in a vigorous anti-imperialism demonstration.

17. Working Class Action against War

The decision of the French workers to adopt these class conscious tactics marks a very important change in the attitude of the working class of Europe toward war. Heretofore, the European workers have been satisfied to carry on general propaganda during peace times and then, when war did break out, to fight patriotically for “victory” and “glory.” Such tactics imply the acceptance of the economic situation out of which wars grow, and merely oppose each particular war as it arises without any effort to get back to its causes or to prevent it at the source.

The French workers who organized the campaign against the Moroccan War of 1925 decided to fight the economic system primarily and the war only incidentally. Their campaign was not so much a campaign against war as it was a campaign against bankers, profiteers and concessionaires whose activities make war inevitable.

Class conscious working class action against war may take several forms. First, there is anti-war and anti-militarist propaganda which points out the causes of war and shows how owners profit while workers pay. Second, there is the propaganda in the shops and in the industries. This may include anything from a boycott or a refusal to handle military stores to a general strike whose object is the paralysis of the government in its effort to conduct the war. Third, there is the propaganda in the army and navy. This propaganda may aim merely to undermine the morale of the soldiers and destroy their confidence in the government, or its object may be mutiny and aggressive refusal of service on the part of the enlisted men.

Anti-war propaganda can be carried on legally so long as the government permits it. Political boycotts and strikes are effective only when the workers are thoroughly united. A general mutiny on the part of the army and navy presupposes a revolutionary situation of a very intense character. The leaders of the French movement steered a course which involved neither a general strike nor a general mutiny but which was aimed to undermine both industrial and military capitalist morale and to lead to fraternization with their fellow workers in the Riff.

‘Stopping a War: The Fight of the French Workers Against the Moroccan Campaign of 1925’ by Scott Nearing. Social Science Publishers, New York. 1926.

Scott Nearing (1883-1983) was a left intellectual and prolific writer on a vast array of subjects. He came to prominence for his outspoken rejection of World War One, a pacifist position he retained his whole life. Joining the Socialist Party and teaching at the Rand School, Nearing was indicted, like so many leftists, under the Espionage Act. Nearing was deeply sympathetic to the Bolshevik Revolution, though he remained in the SP until 1923. His pacifism meant his application to join the Communist Party was at first rejected, though he eventually became a Party member writing for the Daily Worker until he left/was expelled in 1930. Nearing remained a committed left activist and writer, even after ‘going back to the land’ and embracing vegetarianism in the 1930s. He traveled and wrote widely in the post-World War Two era of the Socialist Bloc. Nearing’s work and ideas gained new interest with the New Left, and he was prominent as an elder of the pacifist anti-Vietnam War movement and has a column in Monthly Review. He is the author of well over 100 books and pamphlets.

PDF of pamphlet: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1288&context=prism