The promise of automation for workers to lessen labor, and the its opposite reality under capitalism has been a central contradiction since its application began. No more so than today. Robert J. Wheeler, a member of the Glass Blowers Union, speaks to that promise and reality for the glass blower of yesterday.

‘The Passing of the Glass Blower’ by Robert J. Wheeler from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 8. February, 1911.

MODERN machinery has become a tremendous factor making for ceaseless change in industrial processes and within industrial society. Out of this movement is evolving the new economic system that will solve forever the problem of the distribution of wealth.

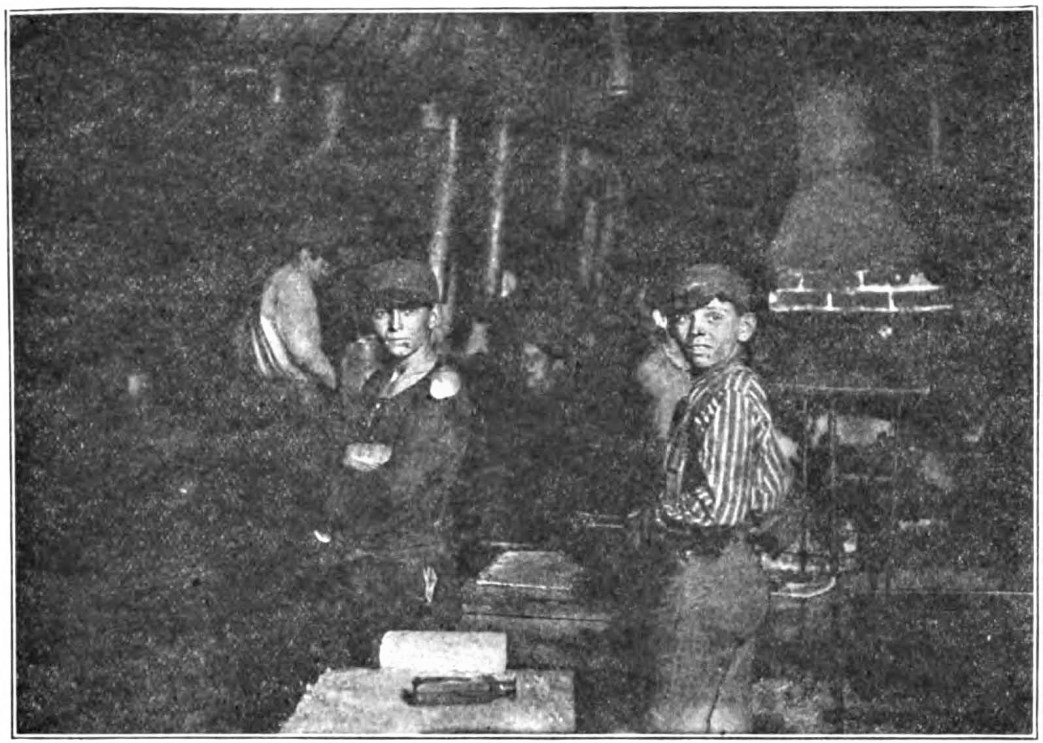

People in general are not aware of the great changes in methods of production or of the revolutionary effects upon the minds of the workers. Society feels, in a sort of sub-conscious way, that machinery is making progress; but it is the particular groups of workers who have been displaced by the machinery, who have suddenly been compelled to face the fact that their means of livelihood has been taken from them, these men and women are keenly alive to the miracles of modern economic development.

Before machinery invades a particular trade, the workers within that group are, as a rule, indifferent to general machine progress and the inroads being made in other trades. But in these days of astonishingly rapid advance in labor saving devices, workers of every craft and calling are coming to realize that no trade is secure; no craft safe in possession of a profitable means of making a living. _Among the workers then, it is no longer a debatable question, but a hard and stubborn fact: machinery is, even now, entering into every branch and department of production. Each year sees faster progress, more wonderful inventions. The automatic stage is being reached. It is no longer a matter of working out an idea that will accomplish a certain part of the production of an article; but to develop a machine that will, in itself, embody every necessary principle making possible the production of a finished article. Henceforth inventors will work toward the ideal, the automatic. We may look for leaps instead of slow growth. The advance will be by “mutations” rather than evolution, as it is commonly understood.

The glass bottle blower’s trade is, at present, a fitting illustration of the foregoing. Within the last six years an automatic machine for producing narrowneck ware has been invented and developed to such a degree that the companies using it now occupy a commanding position in the market. As a result, increasing numbers of skilled men are being displaced; thrown out upon a crowded labor market; compelled to swell the swollen ranks of the unskilled.

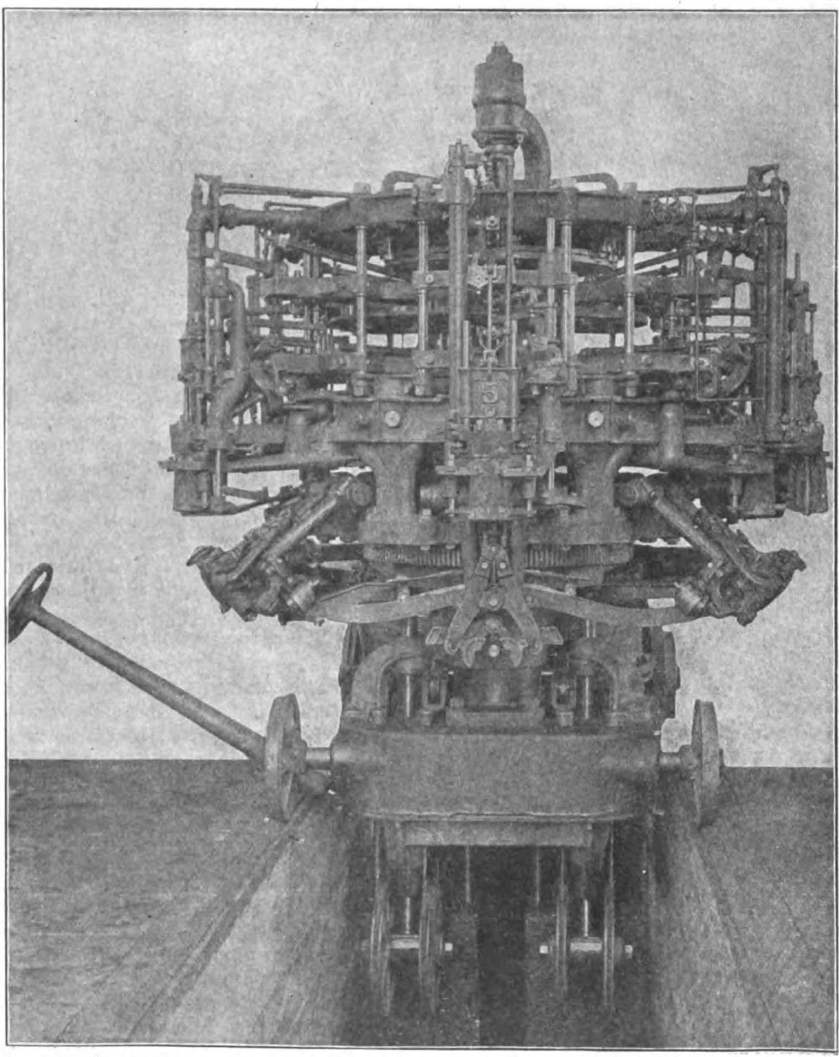

The machine, known as the Owens Automatic, was placed at work in 1904. It is the invention of Mr. M. J. Owens, of Toledo, Ohio. Mr. Owens was factory manager for the Libby Glass Company from 1890. He was formerly a member of the American Flint Workers’ Union, and worked at the trade. Previous to the invention of the Automatic, he had brought out the tumbler machine, the chimney machine, a device for drawing glass tubes, and the idea of pressing the blank shapes to be used in the cut glass trade. These inventions alone are enough to make the man famous. But the invention of the Automatic places him in the front rank of great American inventors. History will credit him with having made possible the application of the modern capitalistic methods to the glass bottle business.

The Owen’s Automatic is indeed a marvel of mechanical ingenuity. To stand beside it, this creature of wheels and cogs, levers and valves, with a constitution of enduring iron; to see it revolve ceaselessly, tirelessly, needing no food, no rest, while from out of the maze of its motions a constant stream of perfect product flows, no human hand aiding, no brain directing, one is profoundly impressed. Here is the very acme of inventive genius. Here is the full fruition of the ideas, the aims, the hopes of inventors since that day, three thousand years ago, when the first waterwheel turned in ancient Greece. The old Greek poet who celebrated that invention in song, beheld with a seer’s vision the dawning of a day when machinery would do the world’s necessary work, and the race of mankind be freed from the slavery of toiling to gain only food, clothing and shelter.

Before the advent of the Automatic, the economic situation of the bottle blower was most desirable. For more than a generation he had been the “aristocrat” of the labor world. After the-successful general strike of 1888, his union became very compact and powerful. With the increase of strength which came as a result of victory in the famous Jersey strike in 1899, and the accession of some 2,000 bottle blowers from the Flint union in 1902, the Green Glass Bottle Blowers’ Association reached the zenith of its strength and power and the period of prosperity which followed was the greatest known in the history of the trade. No craft in America ever enjoyed better conditions. High wages, short hours, almost entire freedom from danger of accident, most excellent working rules, drawn up and enforced by the union, made this period indeed the halcyon days of the glass bottle trade. But those days are past never to return.

The strength of the union grew out of a set of circumstances peculiar to the bottle trade. The business was and is even today, in greater part, carried on by small companies, scattered over the country, located generally with regard to sources of raw material and fuel supply.

The manufacturers, like all small business men, were intensely individualistic and fiercely competitive. Naturally, compact organization among them was practically impossible. Out of this weakness of the employers, the strength of the blowers’ union developed, its greatest progress being made under the presidency of Dennis A. Hayes, who was elected president in 1896, and who still holds the office. The natural difficulty of learning the trade was an important factor in giving the union control. A glass blower is not produced in a few months. To learn the trade thoroughly, several years of application was necessary. This fortified the union was able to constantly improve the conditions of the bottle blowers. The greatest period of prosperity began with 1900 and lasted until 1907. During this stretch of years the business expanded until the demand for men considerably exceeded the supply. The ideal economic condition for labor under the capitalistic system was attained. “The job sought the man.” Wages steadily rose, reaching the highest point in 1907. Fair workmen could make from $6.00 to $8.00 per day of 8% hours. The speeders in Massillon and Newark, Ohio, Streator, Ill., and Terre Haute, Ind., made from $8.00 to $12.00 daily. The work was hard, heat intense, nervous strain great and night work unpleasant, but all this is true of other trades where men are poorly paid and ill-treated. Under the rules of the union, no glass is made in the summer months, July and August. Glass blowers look forward to this rest season with the keen anticipation of men who can afford a vacation and have the money to aid them in enjoying it. Working an eight or ten month. season, men earned from $1.200 to $3,000. This allowed a margin above a comfortable standard of living. Glass blowers live well, try to educate their children, give generously to every worthy cause and have no apology to make that they are not bondholders today when adversity has come upon them. A considerable number are fairly well off, probably as large a per cent as will be found among any other class earning the same amount of money yearly.

The splendid union gave the blowers protection and enabled them to get a large share of the value they produced, but it failed to develop in them an understanding of economic conditions.

And so, at the climax of prosperity, when in fancied security, the bottle blowers looked forward with confidence to even better advantages than they were then enjoying, the blow fell upon them. The machine was invented that has revolutionized the trade and in time will practically destroy it in large part.

We quote from latest news on the Owens machine:

“The machines are now being operated in Monterey, Mexico, a greater number in Germany, and one in Rio Janeiro, Brazil. The Owens Company has received application for the installation of a machine in Johannesberg, South Africa, and in Yokohama, Japan.”

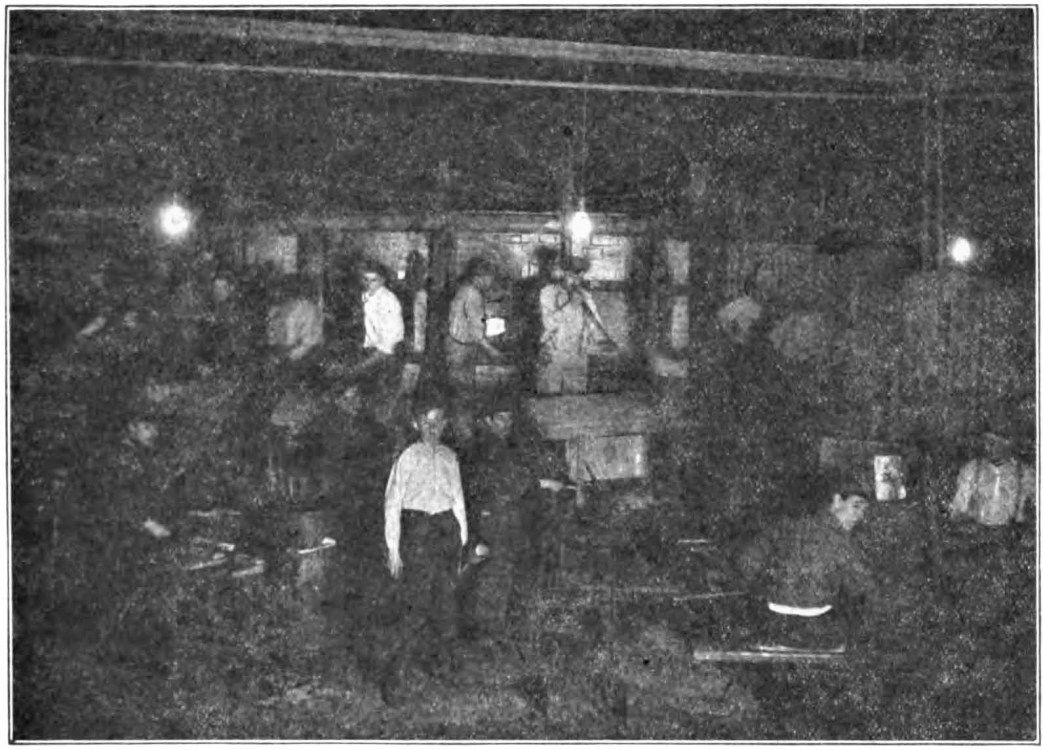

Machines were first installed in old style factories which had been fitted up with the patent Owen’s revolving furnace. Later, a specially designed factory was built in Fairmont, W. Va. A description of this factory, making a contrast between the old and new systems, follows. This is also taken from the “American Flint,” April, 1910:

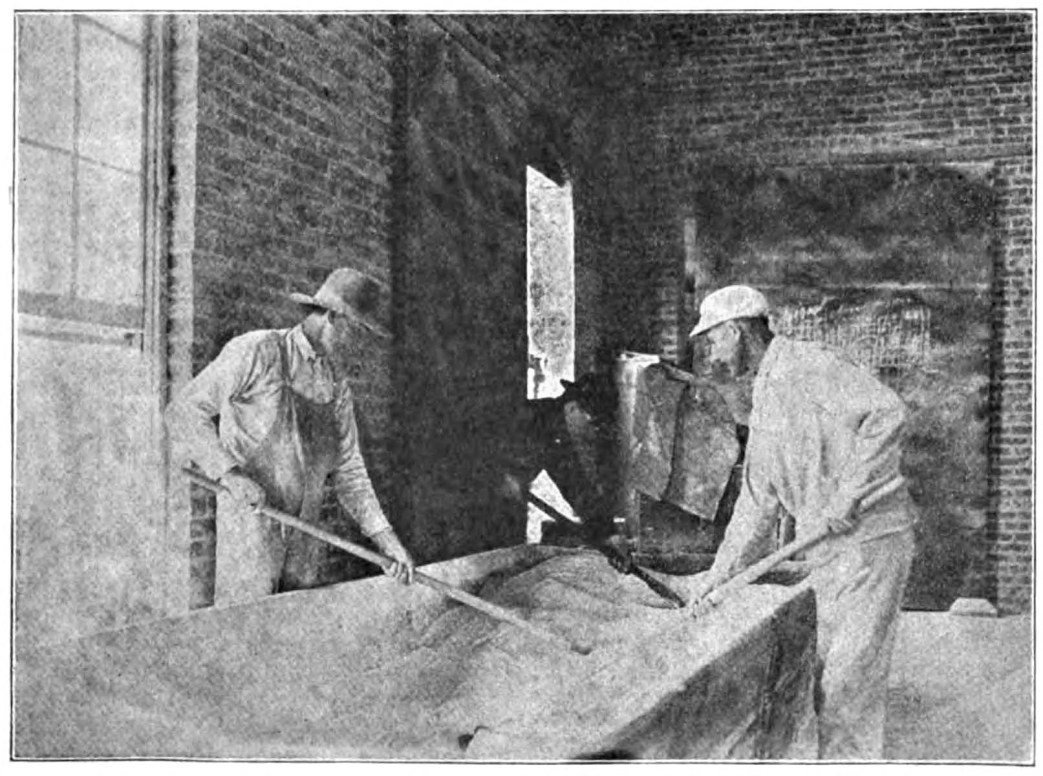

“The factory now being erected at Fairmont, W. Va., which will be put in operation during July or August, will have a capacity of 2,000 gross of bottles a day. This plant will be a marvelous innovation and surpass the dreams of the most sanguine idealist. Under the present system of making glassware the raw materials are. hauled from the mines to the factory and unloaded, mixed, and carried to the furnaces and placed there by the use of shovels in the hands of common labor. After the glass has been melted, it has been gathered from the furnace by skilled labor and manipulated by hand or semi-automatic machinery into bottles. The ware is then carried by boys into the annealing lehrs, and these have always been operated entirely by hand power.

“At the West Virginia plant all of this labor, including the skilled, will be dispensed with. The factory is so constructed that the railroad cars are drawn up an incline 100 feet high, hoppers are suspended in a row and the railroad cars pass right over the tops of same. The sand, lime, soda, and broken glass is mechanically removed from the railroad cars and placed in the hoppers. On the lower end of these hoppers is a measuring spout. By the use of a plurality of valves the quantity of sand, lime, soda and broken glass is measured and put into a traveling mixer beneath the spouts of the hoppers. Aman sits on this traveling mixer and mechanically manipulates the movement of same. After the mixer has passed under the spouts of the different hoppers and received the quantities of sand, lime, soda and broken glass sufficient to make up a batch, the mixing car is started by him for the furnace room, traveling over the tops of the furnaces. The mixer revolves, which properly mixes the batch, and when it reaches the first furnace, a disc is removed from the cap of the furnace and the hopper lowered through the cap of the furnace, the material passes from this hopper into the furnace where the melting takes place. The hopper is then elevated and the disc placed. to cover the hole in the cap of the furnace, and the man returns to the batch house in order to repeat the operation for the second furnace. As the batch becomes melted, it flows by gravity into the revolving furnace used by the Owens process for making bottles.

The machine sucks the glass from the furnace through the bottom of the blank mould, forms the blank, transfers the blank from the blank mould to the blow mould, and by compressed air, expands it into a finished article, glazes the top, the lehrs being part of the machine, anneals the bottle and dumps it out at the exit end of the annealing lehr at which point the wares are selected and placed in crates ready for shipment. The machine has been started to work producing at as high a rate as 23 a minute at 6 a.m. Monday and kept in continuous operation until the following Saturday midnight. Moulds are changed and the machine oiled while in continuous operation.

“An extraordinary revelation connected with this mechanical wonder is that at the Fairmont factory it will not be necessary to touch the raw materials, or wares, from the time the raw material leaves the mines until the selector passes judgment on the ware at the annealing end of the lehr and places it in boxes ready for shipment.

“To give you an idea of the revolutionizing effect of this machine in the cost of production, will state that it is reliably estimated that at Streator, Ill., with a shop of three blowers and the necessary small help making pint beer bottles, and under a 20% reduction in wages, that shop labor cost is approximately $1.15 a gross. By the use of a six-arm machine for making pint beers the labor cost is 11 cents a gross. In Toledo where a ten-arm machine is used for making pint catsup bottles the total labor cost is 4% cents a gross, and it is expected to reduce the Toledo cost when the Fairmont, W. Va., plant is placed in successful operation.”

At this writing, the Fairmont factory is operating. The new style of factory, like the machine, requires but few men to keep it in operation.

The trustification of the glass bottle business is now possible. Before the appearance of the Automatic, the bottle blower, through his strong union, was able to demand and get such a large share of the wealth produced that the profits left to the manufacturer were not large enough to attract men with the genius for trust organization. Then too, the difficulty of organizing the small manufacturer made combination impossible. But now the human labor is thrown out and capital will feel perfectly safe. Permanent investment of capital to any amount can be made with certainty of large return. In no department of industry is the prospect so inviting. There are strong reasons for believing that the foundations for one of the world’s greatest trusts are now being laid. The Owens Machine Company leases its machines on a royalty per gross of bottles made. The bottle business is divided according to different kinds of ware. The practice of leasing the machine only to big firms having large capitalization has been carefully followed. The first company to use the machine was the Ohio Bottle Company, formed in 1904. This company was made up of Reed & Co. and the Pocock Company, both of Massillon, Ohio, and the Everett Glass Company of Newark, Ohio. The next year this corporation merged with Anheuser-Busch with two big plants at St. Louis and Belleville, and the Streator Glass Company, Streator, Ill. This company makes beers, soda and brandy bottles. The famous Ball Brothers, of Indiana, leased the right to make fruit jars. The Thatcher Milk Bottle Company, with factories in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Illinois, has the rights on milk jars. The great Alton Glass Company, Alton, Ill., the Whitney Glass Company of Glassboro, N. J., and the Chas. Bolt Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, and Muncie, Ind., with the Heinz Pickle Company of “37 variety” fame, are all companies with plenty of capital. The significant thing is that these companies are not engaged in competing with each other, with the product of the machine. The import of this will appear later. These companies are well located geographically, a fact which is of much importance if a trust is to be organized. The Owens Company reserves the right to enter the producing field also, and is now operating two plants and selling the product in the general market. It is safe to say that an understanding exists, as to price, between the Owens and other companies. With the Owens Company owning the machines and gaining experience as a glass bottle producing concern also, profits are sure to be immense and combination inevitable.

The large number of small manufacturers, now struggling in an anarchy of competition, are doomed. There is absolutely no future for them. Even should they be able to beat wages down lower than at present (it should be stated that wages were reduced 20% in 1908, and the Owens Company promptly reduced royalties 37%), the Owens people will do as in 1908, reduce royalties even below the hand scale. This would leave the small fellows no better off. The little fellows cannot combine, even though they were able to put aside their intense individualism.

The coming combination in the glass trade will be outside the operation of the Sherman laws. Its activities will be entirely “legitimate.” Its component parts can claim economy as a reason for combination. With each of the big firms making a different line of ware on the machine, the cry of “restraint of trade” cannot be raised. The glass trust will be what Teddy used to call “a good trust.” There will be no occasion for the government to repeat the nice little joke it recently played on the Imperial Window Glass Company. Everything points to combination in the glass business. Perhaps, in time, it will embrace the entire field of glass production, bottle, window, tableware and all other lines. There is an immense field before it. Doubtless the glass trust of the future will rival the Standard Oil.

To the student of economics, the introduction of an epoch marking invention like the Owens Automatic and the capitalistic development which is following, affords an interesting subject for observation. The whole process of capitalistic development of an industry is passing in review before him. He sees the entry of the machine, the expropriation of the workers’ means of living, the rise of the trust, the domination of the market, the elimination of the small producer and the expansion of the trust perhaps into an international power.

An interesting feature of the activities of the Owens Company is the introduction of the machine in undeveloped countries. It is significant of the tendency of modern capitalism to rise full blossomed. in the backward nations. Development will be very rapid, because the most highly advanced engines of production will be utilized. Taken in connection with the cheap labor of those countries, the classical lands of capitalism will soon be face to face with a competition which cannot be met. And all this will hasten the time when the great change will have to come.

True, most of this development is in the future, but these are the tendencies. Glass blowers who can find jobs are still profitably employed; small plants are. still making money; small capitalists are even building new factories. But were they not eating and drinking and making merry before the deluge? Even so today.

The Beginning of the End.

Automatic machinery is the fruit of the final triumph of the race over the forces of nature. Man has become a creator of a being almost as wonderful as himself; a being which will labor without ceasing, without complaining. This new phase of industrial civilization confounds all the capitalist economists. All their smug philosophy with regard to the relations between Capital and Labor become as “sounding brass.” What now becomes of the stock answer they were wont to give to the working man’s complaint? “Capital set free by reorganization and labor set free by industrial development, will, in a free market, unite and develop new industries.” The machine instead of man will be used by the capitalist. With the day in sight when machinery will be doing the greater part in production, while the workers will be idle, who will purchase the product of the machines? Face to face with this problem, the capitalist economist becomes a discredited counselor. The working class alone can solve this problem.

When in.retrospection the economic history of the race is passed it will be a wonderful story. Behold man the savage in his home in the primal forests, most of his needs supplied to him by nature. His existence was no more a burden to him than is that of the bird. See him again, when pressed out of his primitive abode by ever increasing numbers, he is forced to seek a better means of food supply. He begins to invent crude tools and discovers the arts of agriculture and manufacturing. Necessity drives him as a taskmaster. He has never been a willing doer. Even though he has labored hard and builded wondrously, yet his aspirations have been toward a state of existence where the weary would rest and the toil-laden be relieved of their burden. All his efforts in his upward journey have been towards the creation of tools, which producing the means of life for him, would permit him to live again, as in his earlier history, without constant toil. The way of the journey has been a rough one; the hindrances mighty, and myriads of men, through the uncounted centuries have toiled and suffered and discovered and died, leaving the final consummation to the men of today.

And now the mighty work is almost finished. All the important forces of nature have been harnessed to provide power. The machine which can produce without human labor is here. The principle is being applied in every department of industry and as the processes are simplified by subdivision, will perform almost every part of the process of production. There remains but one step more and the goal of economic endeavor is reached and the race made free. Again, as in the beginning, necessity is the driving force. The mass of men made jobless by machinery are facing the age-old question: “What shall we do for food?”

Until this question is answered, further social progress is impossible. Civilization is marking time, gathering power for the next leap. From the working class must come the action that will let loose this power. The machinery must become the property of the workers.

So the glass blower is passing to join the army of outcast workers. A multitude precedes him; a multitude follows— but not to despair. Necessity is compelling; education is preparing and hope is beckoning them to unite and overthrow the capitalist system.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n08-feb-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf