One of the most nuanced and fiercely fought debates of the Revolution in Lenin’s life was the role of the trade unions in the new proletarian state before and during the 10th Party Congress in 1921. The debate was largely held in public, as this intervention from Karl Radek published in the I.W.W.’s ‘Industrial Pioneer’ attests. The, more or less, three-way conflict was between Trotsky, Krestinsky and supporters favoring integration of the unions into the state, Lenin and Zinoviev’s position of continued union independence, and the former Workers Oppositionists around Alexander Shliapnikov favoring union control outside of the Party. Karl Radek would support Lenin and Zinoviev’s stance, though he honestly describes the opposing positions.

‘On the Threshold of the Great Work of Reconstruction in Soviet Russia’ by Karl Radek from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 3. April, 1921.

I. THE ROLE OF THE TRADE UNIONS IN RUSSIA

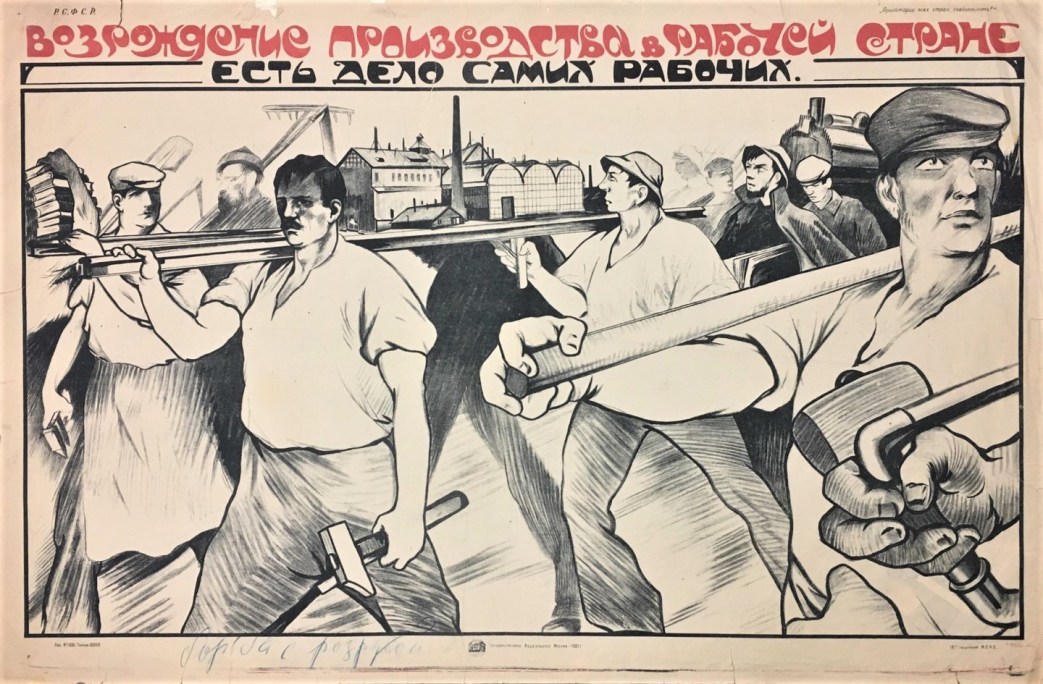

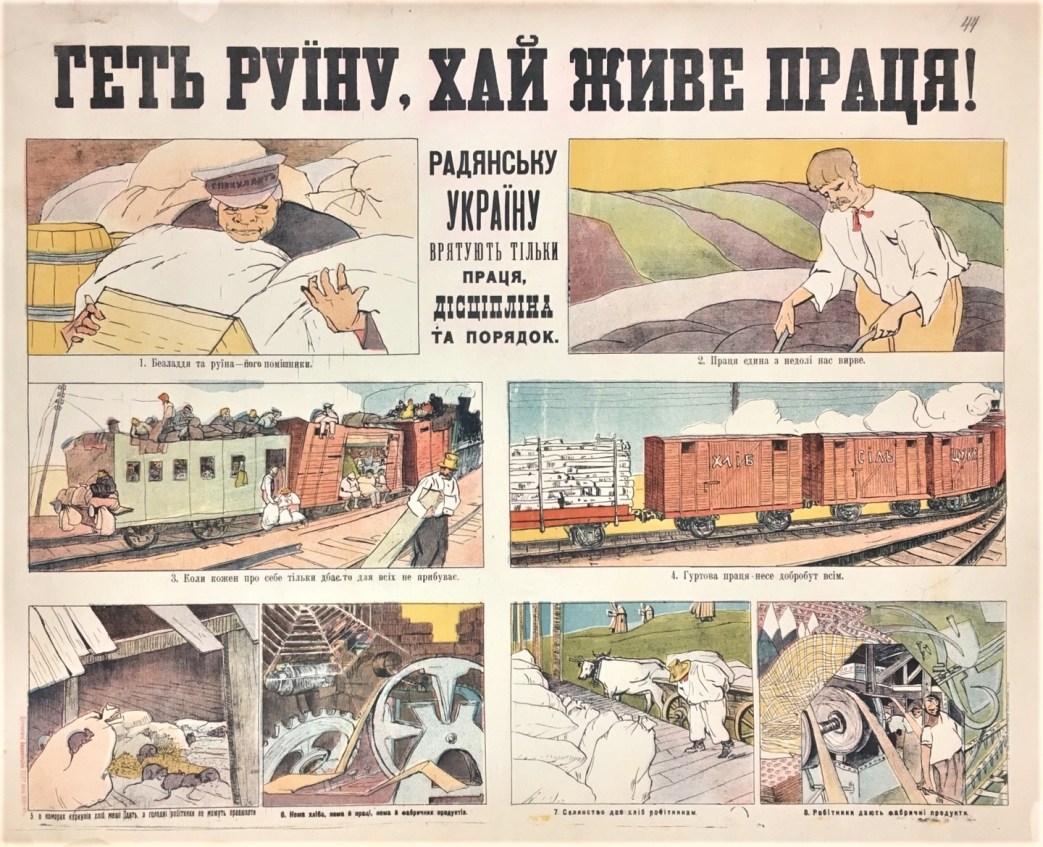

WORK — that is the password that lives in the consciousness of millions of adherents of the Soviet, and which must he translated into knowledge and faith on the part of all the working masses of Russia. Indeed, all the differences arising within the Russian Communist Party grow out of the difficulty of grasping the complicated conditions in which the process of economic reconstruction must proceed. In this article, which is to serve foreign comrades as a guide, these differences may best be presented by directing attention to the conditions under which the Communist Party has to execute the decisions of the Congress of Workers’ and Peasants’ councils.

Soviet Russia is a country with an 85 per cent agrarian population. The Soviet government is not a purely industrial government. It called itself from the first day of its existence a Workers’ and Peasants’ government. Many of its opponents and adherents believed that this was merely a nominal title in order to lure and quiet the naive little peasant; since the government is entirely in the hands of the Communist Party and since the left-wing social revolutionists have deserted it, this erroneous assumption seemed even more justified. But this was incorrect. Simply because no peasant party sits in the Soviet government, the millions and millions of peasants in Russia do not disappear. Without their cooperation neither the defense nor the reconstruction of Soviet Russia is possible. In the Red Army, which in its majority was a peasant army, the class consciousness of the peasant was made keener, and political intelligence was imparted to them. Altho they take no part in the government thru a separate party, the government is compelled to consider their interests and their sentiments. Now, when the peasants have the feeling that the danger of the return of the Junkers has disappeared, now when the government must demand fresh sacrifices from them, in order to bring industry into operation, thru the assurance of provisioning the city population, the government must naturally give the peasant class special considerations.

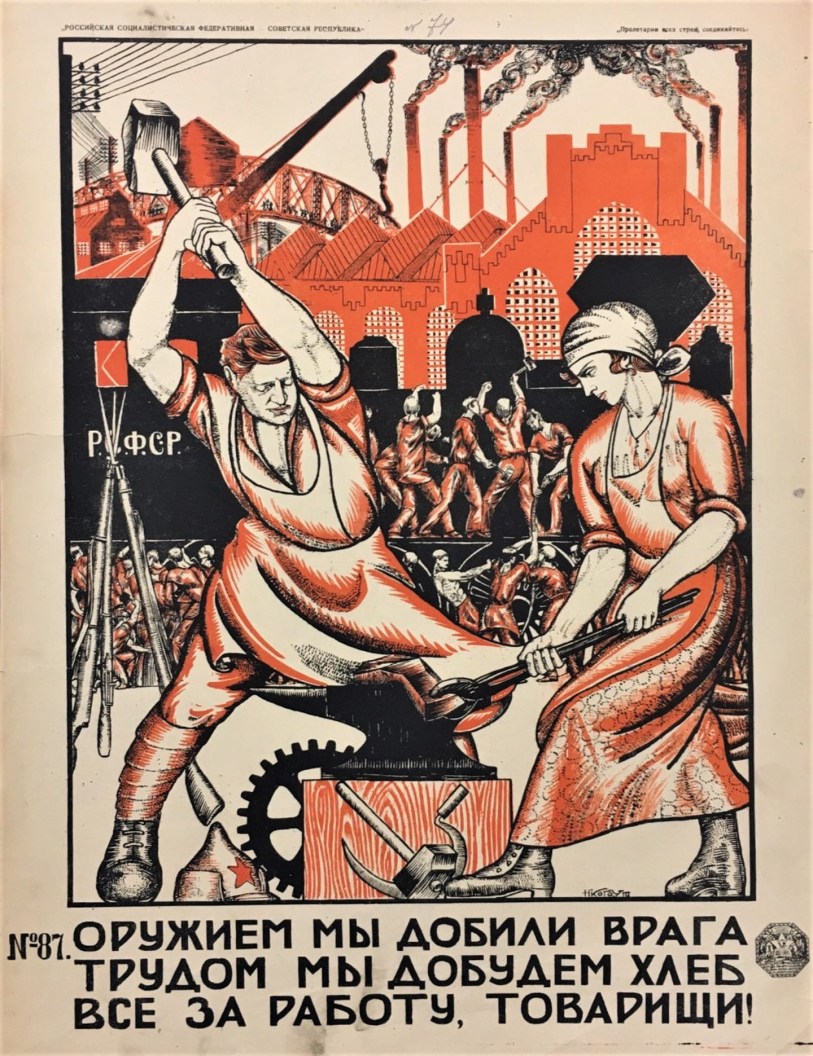

After three years of imperialistic wars, the industrial classes have bled and starved for another three years for the dictatorship of the workers. Tortured by hunger and cold, they have often wavered and hesitated. But always the Communist Party was able in the hour of danger to arouse in them the necessary energy to continue the work in the factories and to place a hundred thousand of them at the head of the administrative machinery of the state and at the head of the army.

Not only did they hunger for victory and fight for it, but they renounced a great part of the rights which belonged to them according to the Soviet constitution, and which needed to be sacrificed on account of the dire necessities of the war. Since their most energetic leaders were at the fronts and were sent on economic and administrative missions from one end of great Russia to the other, the proletarian mass organs of the dictatorship, the Soviet and the unions, were crippled. The working class was compelled to yield when, in place of their elected representatives, frequently revolutionary and non-revolutionary bureaucrats took matters into their hands, which must inevitably lead to special abuses in an impoverished country. They had to exercise patience, when all available clothing was reserved for the army, when bread went to the front, while they received herring-tails or raisins. Now the possibility of peaceful labor for a certain time appears to be at hand. If it was possible during the war to charge all abuses and deprivations to the account of the war, the masses must now be given the possibility to find for themselves the means for removing the abuses and diminishing the deprivations, and to convince themselves how much of their burdens can be removed, and what they must still bear for the purpose of overcoming needs. The dictatorship of the proletariat was not suspended, as the Mensheviks of the whole world shrieked, when the organs of this dictatorship were restricted. But now when, perhaps only temporarily, no war exigencies require the mailed fist of the proletarian dictatorship, the needs of the hour demand that the organs of the dictatorship be restored to that class the defense of whose interests constitute the real purpose of the dictatorship.

The trade unions, which the Bolsheviki had already captured under the rule of Kerensky, have fought during the three years of civil war side by side with the party, with the Soviets, in a true sense of the word, for the maintenance of the dictatorship. Not only did tens of thousands of members of trade unions go to the various fronts because of mobilization, but other tens of thousands went voluntarily and fought with weapons in their hands as soldiers or Red officers for the workers’ dictatorship. When the Soviet Republic needed thousands of experienced men for the organization of provisions, the trade unions gave them. And when the hungry workers in the factories grumbled, when it was necessary to get seamstresses to produce 15,000 army coats a day, altho they were hungry, cold and bare-footed, these trade unionists went to the factories and to the homes of the workers in order to overcome their fatigue thru persuasion and explanation and to make them forget their hunger. On them primarily the masses exercised pressure, and they who had been until now accustomed to the organization of the battle corps, for the improvement of the condition of workingmen thru strikes, were compelled to make it clear to the masses that only thru work can the needs of a proletarian regime be met. Quite true, the trade unionists, oppressed thru too great a division of labor, are not even in Soviet Russia people with the broadest mental horizon. They have not sufficient leisure to think out all connecting issues, and yet they frequently take more sober thoughts than those leaders whose task it is to keep their eyes directed towards the entirety. As all of Russia, they were continually diverted thru the civil war from adjusting the problems of production, altho they recognized, ever since the first congress, held after the October revolution, the role which the trade unions must play in production. The trade unions comprise 7,000,000 workers. It is clear that under the conditions of Russian transportation, with the small number of trade unionists left by the war in the trade bureaus, they could not remain in sufficient contact with these masses. But that does not alter the fact that these seven millions of more or less organized trade unionists are the proletarian basis of the Soviet; government, that the comrades conducting the trade unions and the 500,000 Communists in them are the connecting link between the six and a half-million and the Soviet government.

These premises are not grasped with sufficient completeness in a first attack on the problems which confront the Soviet government and the Communist Party by all comrades or by all groups which have crystallized out of the party. Industry can only be built up when the independence of the working class is developed. The organs of this mass, if they are to be separated according to kinds of production, are the trade unions. Therefore, the control of production must lie completely in the hands of the trade unions — so declares a group of the unionists under the leadership of Comrade Schlapnikoff. The unions will succeed better with the problems of production than the best workers’ bureaucracy, to say nothing of the civilian specialists who, accustomed to large means, are compelled to go slow in view of the poverty of technical equipment in Soviet Russia, even if they were able to handle the workers properly or to arouse in them the necessary enthusiasm.

This tendency overlooks a small fact. In a country with 85 per cent of peasants, the re-construction of industry is impossible without the confidence of the peasants that their interests shall be considered, that they shall not be plundered by the industrial workers. If the industrial economic plan can be accomplished thru an organization formed from representatives of the production unions, the general economic plan cannot conceivably be accomplished without the co-operation of the organs of the state, which have to put in order the agrarian question and that of matters of subsistence, and which are not constituted of trade unionists. Only a general economic plan should be considered, because bread is as necessary for industrial production as coal and iron. This point of view alone makes it impossible to hand over the direction of industry exclusively to the unions. Also, there has accumulated in the general economic organs of the state a mass of experiences which cannot be discarded; for instance, the enrollment of the specialists, as long as they have not been completely assimilated by the unions, can be more easily done by official means than thru the medium of the unions. Then there is the further consideration that the unions — certainly not thru their own fault, but owing to the conditions under which they have functioned — are very little prepared for the direction of production. Their technical comprehension is small; even their production propaganda is in its infancy.

This last observation is the point of departure of the position of Comrade Trotzky and a group of very competent unionists like Holzmann and Kasior. The latter emphasize the weaknesses of the union and, besides, insist that in their present state the unions are still incompetent to conduct production. But yet they consider the direction to be the task of the unions in a proletarian state. Thence they conclude the necessity of reconstruction, of reorganization of the unions. Thence also comes their preoccupation with thoughts of production and their induction of new members who have learned in the economic organizations and in the Red Army to direct great enterprises unemotionally and energetically. Their point of view tends to reform, with all their powers, the unions from the top down, that is, to take away a part of their, independence, in order that they may become in the future the directors of production.

What has been said above concerning the direction of producing thru the unions in the discussion of the point of view of the group of Schlapnikoff, we need not here repeat for the group of Comrade Trotzky. The same is true here. What should specially be considered in this case is the danger of his conception that the unions have no task but to increase production. One might perhaps accept this formula, for in a workers’ state every organ of the mass of the workers must serve the principal task, and that is production. The points which make Trotzky’s passionately maintained point of view dangerous are the following: In the unions we have only half a million Communists against six and a half million workers without party. This indicates how great is still the function of the union as the educator of the masses towards Communism and as the intermediary between the Soviet government and these millions. Trotzky is, indeed, quite right when he maintains that this educational function cannot be accomplished outside the demands of production, but he cannot deny that there is an independent problem, a problem which in the first place consists of the great task of persuasion, and not primarily of direction or command. When Trotzky declares that in a workers’ state, not the unions but the government must care for the material welfare of the workers, he tells only a part of the truth. Lenin is entirely right, when contrary to Trotzky, he declares that the Russian government is a government of the workers and the peasants. If weapons like strikes are inadmissible and unnecessary against such a government, there is not the slightest doubt that the state has an interest in controlling a mass organization which feels the pulse of the workers and which is always concerned in securing as much as possible for the workers from the state. One might complete the thoughts of Lenin to the effect that because no peasant party is represented in the workers’ and peasants’ government, which might represent the peasants’ interests in the coalition by means of pressure on its partner, the battle between the workers and the peasants is conducted in the heart of the Communist government itself.

The latter has always before its eyes an 85 per cent peasant population and an industrial population of only 15 per cent. This may often lead to slips and errors of calculation. If the government wishes to retain under its feet its only secure basis, the proletarian, it is to its interest to be subjected constantly to the pressure of the unions, its constant controlling factor. The second danger in the attitude of Comrade Trotzky lies in the fact that the reconstruction of the unions from above may easily lead to their bureaucratization and militarization. Specifically, for this reform, there should be considered the tens of thousands of comrades who have during the last two years passed thru the great school of the Red Army. Now, Trotzky is entirely right when he calls attention to the fact that the Red Army was by no means formed solely thru compulsion, not even primarily so. Conviction, spiritual persuasion, played a great part in its formation, and the comrades who have formed the army are most certainly equipped to hold places of command and advice in every other post under the Soviet Republic. However, the differences in the methods of work on the field of attack and in industry are immense. Where every error may cause the death of hundreds, where one must decide the most important matters in a few minutes, cooly and unemotionally, and must carry them thru, the will to command is of more importance than the will to convince. Truly, the questions relating to the rebuilding of production require energetic attack; not an easygoing direction, but the will to have things moving in the shortest possible time. But since psychologically the consciousness of danger, due to delays in the factory, does not burden the masses as much as on the field of battle, every harsh attack would damage production, rather than promote it. Naturally, the Soviet government cannot renounce compulsory measures against comfortably negligent elements, simply because they hold the labor club, but its main method must be persuasion, agitation, which work more slowly but all the more surely.

II.

As in all discussions, opposed points of view are crystallized into catch-words, or are at least so characterized. Thus the position of Schlapnikoff’s group is known as “Syndicalists.” That of Comrade Trotzky has adopted the slogan of “Production Democracy,” but is called by its opponents “Bureaucratic Militaristic.” That of Lenin is spoken of as “Worker Democracy.” All of these designations have only very limited value. The tendency of Schlapnikoff acknowledges the dictatorship of the proletariat, the proletarian state, which was never true of the Syndicalists. Those circles of the party grouped about Trotzky do not consist of bureaucrats nor of military blusterers. They represent, so far as their energy goes, by no means the least considerable portion of the Communist Party, and their military gruffness is of too recent origin to have a permanent effect on their characters.

Trotzky’s own choice of a slogan, “Production Democracy,” need not be contradicted on theoretical grounds. Democracy is the system of the bourgeoisie by which it rules the masses, giving them certain political rights but keeping in its hands all means of production. In speaking of a Workers’ Democracy, the addition of the term “Proletarian” indicates that the tools of production and the power belong to the proletariat; in short, that the old political conception of democracy has succumbed to a gentle disintegration. The use of the concept “Workers’ Democracy” has also the specific purpose of accentuating that the proletarian dictatorship is coming or seeking to come to the position where it will, not only be supported by the working class, to defend their interests, but also to represent them thru the mass organization of the proletariat. Production democracy has no meaning at all unless it be an interpretation of the motto: “Who does not work shall not eat.” In this is expressed a means to an end, but not the purpose of the dictatorship of the proletariat. But we may well drop these explanations of the history of dogma, for Trotzky is not concerned with the introduction of a new theory or the proclamation of a new policy, but rather with avoiding the accusations that he is developing production by militaristic-bureaucratic methods. He is concerned with the determination of a universally acknowledged fact, namely, that the Proletarian Democracy in Russia can only maintain itself by learning to produce.

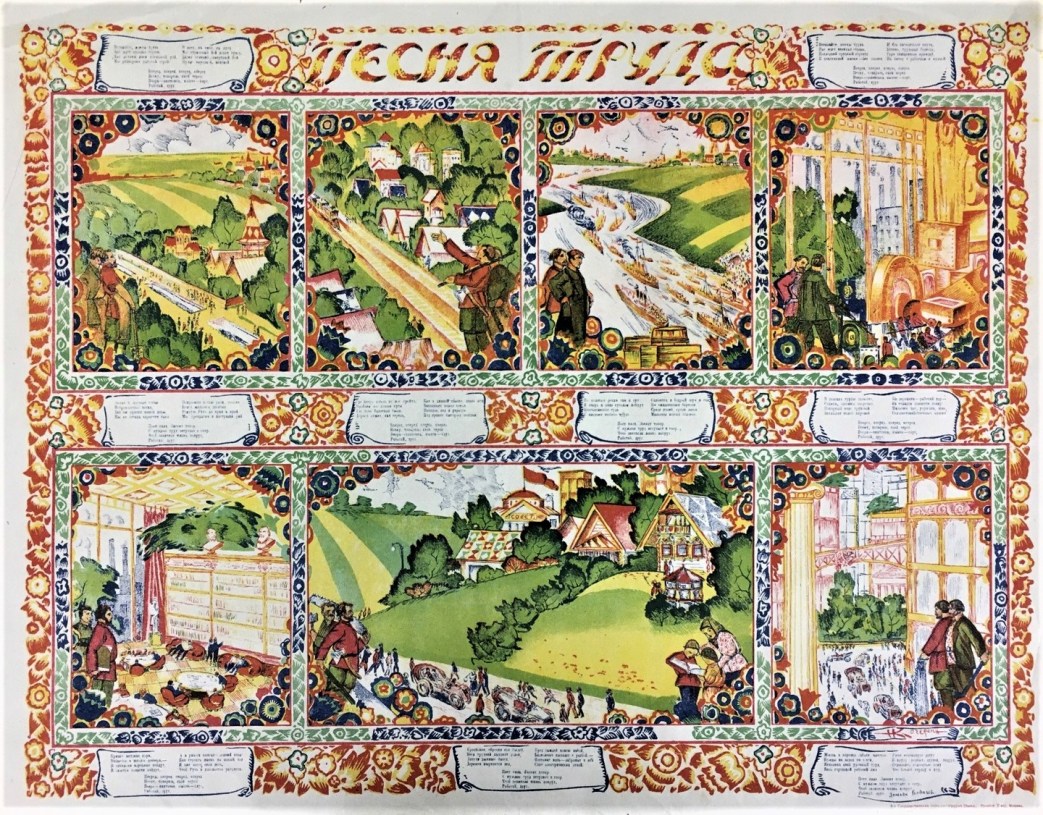

And that it will do. It will do so because there is in the Russian working class, in the Communist Party, enough energy to make that Soviet republic, which they have defended on the field of battle, secure thru their labor. In this the entire Communist Party, enough energy to make that Soviet Republic, means are of such a nature that they could not grow into antagonisms, which might impede the increase of production. The Communist Party is completely in agreement that the unions must participate in this work in growing measure. Even their program declares this. As soon as the trades unionists return from army service and get back to the trades and shops, the increase of their participation in the direction of production will follow of itself. Nobody can or wishes to renounce their aid. That Schlapnikoff’s demand for the transfer of production to the unions is not absolutely law and gospel is quite apparent from the simple fact that the great majority of unionists themselves admit themselves to be for the time being ill adapted to exercise this function. Should we then attempt to adapt them by throwing them into the great kettle to be stewed and roasted into condition under the direction of the military and economic cooks? The military comrades themselves must first adapt themselves to the new tasks in economics and they have not less to learn than the unionists, altho possibly in other directions. Is the party to renounce the persuasion of the unions? No one dreams of it. Anyone who reproaches a Lenin or a Zinoviev because they are basing themselves on the neutrality of those unions, which they have fought all their lives, makes himself ridiculous. Naturally, the party to whose discipline the comrades in the unions are subjected as much as all others, will permanently control their policies, because the party is the most exalted instance of the labor movement, because it alone has a comprehensive theory of the labor movement. But it will do its duty to the unions with the understanding of the special tasks and methods of the unions. It will carry this out not in a spirit of guardianship but in the spirit of broad communistic guidance.

The influencing and adaptation of the unions to their new tasks are not new problems in principle but are new as parts of a program to the extent that they now confront the proletariat; and to these problems the party will direct all the forces available. Among these are the competent comrades from the army and economic organizations. But the party will say to them: You are not entering the unions as clever instructors for stupid unions, but so that you may adapt yourselves to the new tasks and learn to execute them. The union organizations daily take a great part in the conduct of production. The differences between the concrete proposals of the various groups of the party in reference to this participation are not at all great. Actual experience will have to show what must be added and what subtracted in this field. Inasmuch as the unions, in their entirety or possibly by special adjustments, become more and more incorporated into the direction of production, they will not become bureaucratic chancelleries.

For the achievement of their tasks they will not at all need to be officialized formally. Quite on the contrary, official government adoption would only hinder them in the execution of their tasks. So long as only a half-million of the seven million trade unionists belong to the party there is the proof that they are not yet filled with the spirit of communism, the foundation of the Soviet Republic. Under these circumstances the formal officialization of the unions would only impede the Communists in the accomplishment of their tasks. The unions will exercise governmental functions and the better the Proletarian State and the unions co-operate the sooner will reluctance to an official adoption disappear, but the more certainly also will such officialization become unnecessary.

This is the status of the debated questions of the Communist Party in Russia. The bourgeois press and the Mensheviki have always prophesied that the Communist Party would perish because it had throttled the workers’ democracy, the freedom of discussion in the ranks of the working classes and their organizations. Now that the party is discussing publicly the differences of opinion concerning the unions as it discussed those arising from the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and those concerning the organization of production, in order to arrive at a unified decision of this important question of the Russian revolution, the bourgeois and mensheviki press is prophesying that the Communist Party of Russia will perish because it does not hush up its disagreements but discusses them. It is the strength of the Russian Communist Party and working class that they understand how to waive discussion when the moment of battle has arrived and that they discuss, and discuss thoroly, when preparations for new battles are the subject. The discussion has already polished off some of the rough spots. And when the party decision will have been reached the party will stand like a “rock of bronze” on which the enemy will break his teeth. The great task of economic organization will be completed even if our enemies disturb us. The congress of workers’ and soldiers’ councils has submitted to the Russian working class and to the world proletariat no plans which can only thrive in an idyllic world where the sheep and the wolves pasture peacefully together. The plans are battle plans against the bourgeoisie of the world. If we get a breathing spell these plans will be completely realized. If we are compelled to fight on with weapons in our hands only a part of the great plan of construction can be realized immediately; but the world bourgeoisie will have to repay for this disturbance of our labors. In a battle with arms we will secure the necessary conditions of a reconstruction, possibly somewhat retarded but all the more complete.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(April%201921).pdf