Transcribed in full for the first time, Sylvia Pankhurst travels to Ireland during its revolutionary period, gives a survey of recent Irish labor history, and reports on the state of the workers’ movement, the Limerick Soviet, and the character of Sinn Fein.

‘Labor and Sinn Fein’ by Sylvia Pankhurst from Socialist Review. Vol. 8 No. 5. April, 1920.

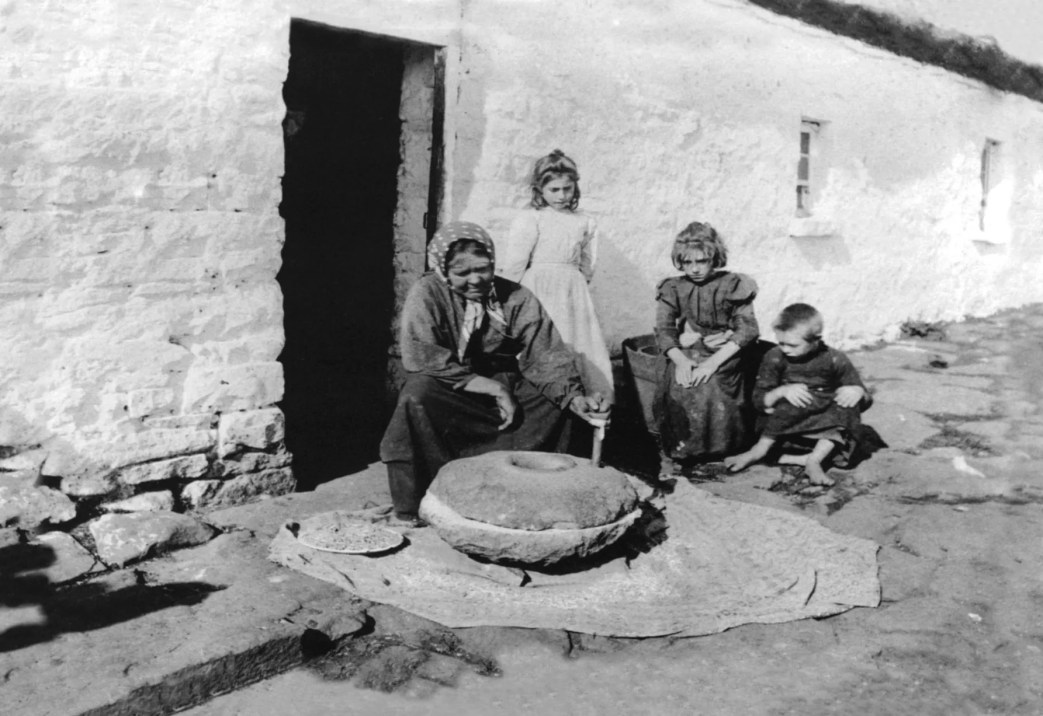

TRAVELING westward through Ireland, we pass stark ruined buildings- factories or monasteries. The tiny hovels of the workers, their walls of rough boulders from the mountain side, and roofs of turf, seem to be cowering in the crevices as though in fear of this bleak isolation. Many of these too are lying in ruins; the reduction of the population means that they are not needed now. Agricultural production, the chief means of livelihood here, is at the minimum. Tiny pieces of earth are cultivated after a fashion; amongst the scant crops bright flowers and weeds run riot, great rocks poke through the thin soil, small spring, well up and spread in boggy patches. Everywhere is the grey-brown peat, miles upon miles of it.

The West Country

In the wonderful west country the soft rain is often falling, the black cattle roam over the fine pale sand of the seashore, and the waves leave behind them countless bright little lemon yellow shells. The mountains are blue in the distance, red flowers glow in the fuschia hedges. The children, fine featured, and olive skinned like Spaniards, run bare-legged, swarming about the tiny hovels. Donkeys bray, poultry clucks, half-wild dogs dash out, growling and showing their teeth at any stranger, and followed by tall black-bearded men, barefooted, bare-chested, their old clothes only just able to hang upon them. Girls with large sun-filled eyes and flowerlike faces tread lightly with naked feet along the roadside. Irish women pass swiftly from lovely girlhood to a gnarled old age. Majestic in their dignity, tall, finely shaped, deep eyed, great hearted, they are the finest things in Ireland. They, too, are shoeless, and their abort homespun skirts are dyed by themselves with a terra-cotta dye they make from the seaweed.

Rack rents are extorted from the small strips of poor land and hovels built by the tenants, the walls of roughly piled stones they collect, the roofs made of turf they have cut from the patch, the floor just the earth trodden over, that was left when the turf for the roof had been cut away.

In the winter, men and women wade into the sea, up to their necks in the cold, cruel water, to win the seaweed, “kelp” as they call it. To render the seaweed marketable it must be burnt on the beach, and they must pay the landlord for allowing them to set light to little heaps of it on the lonely waste of pebbles. The miserable kelp industry is said to have improved during the great war, but government blue books state that in 1916, in the best districts, an entire family could make no more than twenty pounds sterling out of it in an entire season. Years before when the cost of existence was lower, double that sum could be made.

In order that families may be able to pay the charges with which the exploiters load them, the Congested Districts Board, a so called Charity, under the auspices of the British Government, finds home work for the women, crochet or lace making at 85 cents to $1.75 a week, sock knitting at 21 cents a dozen pairs. The total earnings in the lace making trade thus fostered were $144,297 in one year, 1912-18. By 1914-15, they had fallen for the year to $56,848. In 1914, Ireland lay at the depths of her most helpless misery.

To relieve this bleak poverty, and to subsidize also the rapacious landlords, came the earnings of far away sons and daughters. American dollars were as commonly changed as British money in West of Ireland village stores. Amongst the shawled, short-skirted girls and women, sometimes was seen one wearing a hat and city clothes-a daughter home from America, who had brought a parcel of white-handled knives and forks, and had announced that father must build a new room to the house.

Transport Workers’ Strike

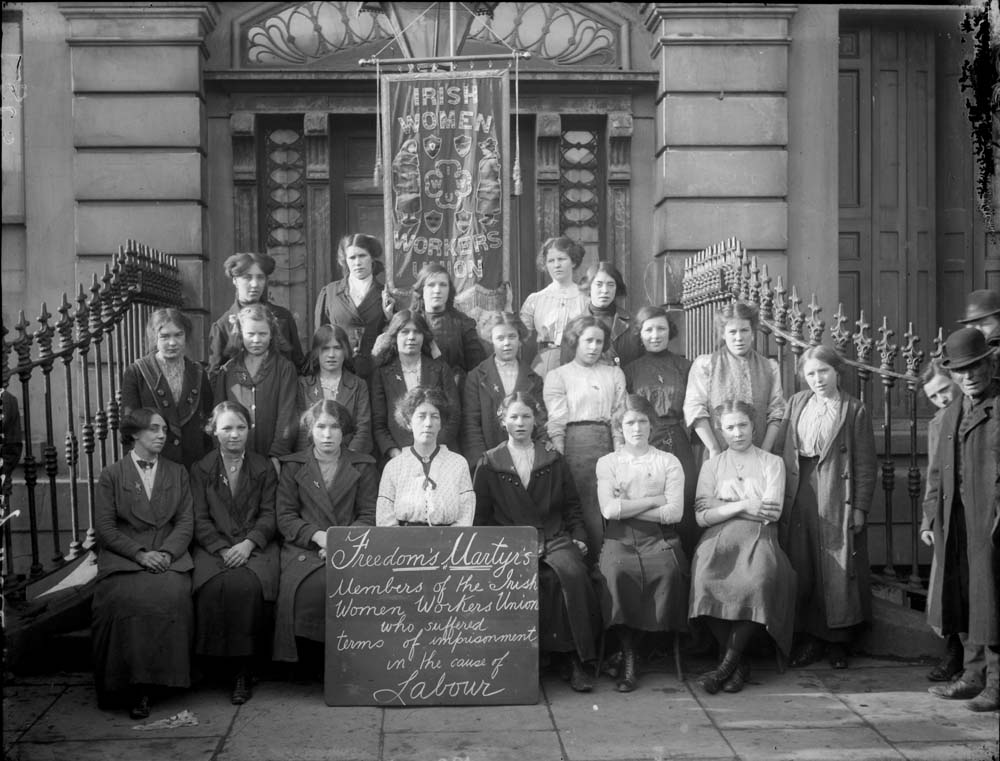

Unhappy Dublin. You seemed like a lovely woman stricken with melancholia. Your gracious buildings, wrought with fine taste and skillful craftsmanship, were fast decaying. Your stately mansions were now overcrowded tenements. Your workers were degraded to the most appalling poverty, ground down alike by British and Irish employers. Then came the terrible lockout which lasted from August, 1913, to February, 1914, and in which 404 Dublin employers tried to enforce upon the workers a written pledge against trade unionism. The transport workers were first affected, but 20,000 men and women joined in the struggle under the leadership of Connolly and Larkin. Irish labor then called to British labor to refrain from playing the part of blackleg by sending goods to the employers, called to British labor to blockade Ireland as a pariah country which degraded its workers far below British standards. The appeal was in vain; British trade union leaders, as usual, failed to rise to the call of working-class solidarity. With a gesture of patronage they gave, instead of comradeship, inadequate gifts of food, mere charity, accepted of necessity and with bitterness, as is always the case with charity.

At last the Irish workers were defeated by hunger and violence, the police in attacking them even entered their homes, and struck with their batons children and bedridden people. The strikers returned to work without a concession from the employers.

The Nationalist Movement

Irish labor had reason indeed to be disillusioned with its nationalism, but internationalism, too, had failed it. Had British labor responded to its appeal, a knowledge of labor’s class solidarity and common mission throughout the world would have awakened in that period of intense struggle. Even as it was, the Irish labor movement received a new and permanent impulse toward class consciousness at that time.

Nevertheless, the Irish Transport Workers’ Federation was broken, and had to be built up anew from the very foundation, and the revolting spirit in Ireland turned very largely into nationalist channels. The passage and subsequent holding up of the Home Rule Act by the creation of the Ulster volunteers and Ulster’s threat to fight, brought the political question of Ireland’s independence into prominence. The Irish volunteer force also came into being. It was composed of Fenians, Sinn Feiners (who then were only a very small party), Parliamentary Irish Nationalists, workingmen and youths of the middle class who belonged to no party at all but were eager to fight for Irish freedom. Ready to muster with the rest were labor’s volunteers, the Citizen Army, as they were called, originally formed during the great lockout to protect the workers from attack by the police and soldiers.

The next significant landmark was the attempt of the British military to stop Nationalist gun-running at Howth (though Ulstermen had done the same thing with impunity), and the firing upon the people at Bachelor’s Walk, Dublin, by the soldiers returning from the encounter, because people jeered and children threw banana peels.

The pale daughter of one of the victims shook her fist at the passing soldiers, crying: “You killed my father.” The parents were weeping for dead and wounded children. Then suddenly the war came. The shooting had occurred on July 26th; on August 4th, the day Potsdam declared war, was held the inquest on the victims. A resolution stood in the name of the Lord Mayor of Dublin, to be moved at the City Council on August 5th calling for the dismissal of the permanent officials of Dublin Castle. A motion by other members demanded the recall of Lord Aberdeen, the Viceroy, and Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary. But the war had come, and had changed men’s opinions. The Councillors stood outside the Chamber, and did not go in to form a quorum: the roll was called eight minutes before the time: there was no quorum, the council had to adjourn. The affair of the shooting was officially buried forever, as far as the Dublin City Council was concerned.

That night the first batch of Reservists left Ireland for England and the war, singing, fighting, and very drunk. The women clung to them crying. The Dublin quays were thronged with cheering crowds. Ireland seemed to have buried the hatchet: British statesmen referred to her as the “one bright spot.”

The Sinn Fein Rebellion

Labor and the Fenians were now fast drawing together. It was they who created the Easter Week Rebellion of 1916. Sinn Fein is the name that is now connected with the rebellion, but, as a matter of fact, the Sinn Fein organization did not make the rebellion, and of the seven men who signed the Republican proclamation only Sean MacDiarmada called himself a Sinn Feiner. Arthur Griffith, the leader of Sinn Fein, took no part in the rebellion and remained indoors when the insurrection began. Some report that he said he must stay at home to mind the children, others that he was a pacifist, and others again that he was too valuable a thinker for his life to be jeopardized. In the great labor struggle of 1913 Griffith had strongly opposed the workers, dubbing their fight against the oppression of Irish capitalists “injurious” to Ireland.

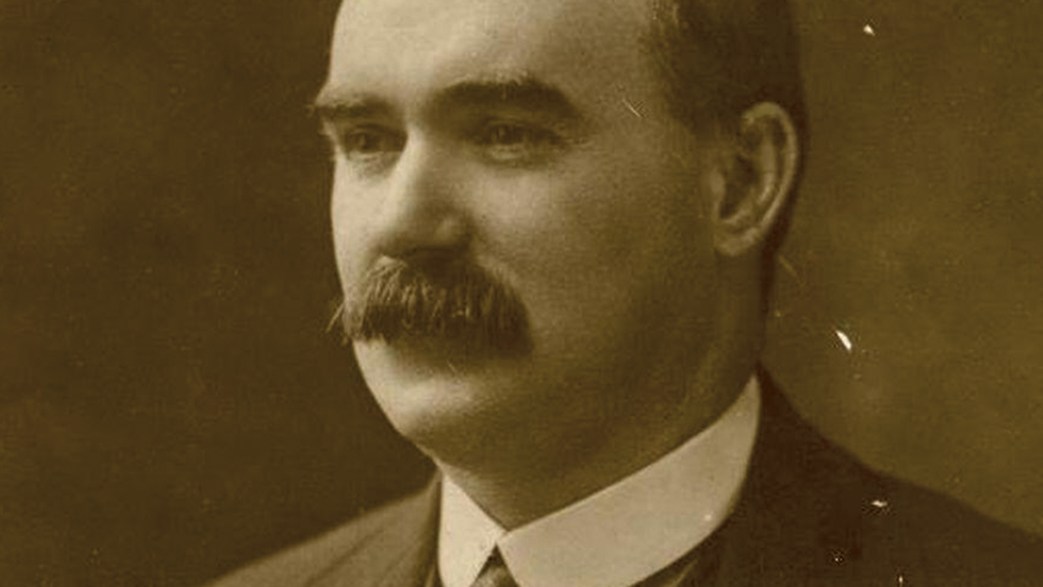

James Connolly

James Connolly, the acknowledged leader of labor and socialism in Ireland, was by far the most important figure in the rebellion. British socialists, who had often heard him insist that capitalism was the chief enemy of the workers in all countries and in Ireland like the rest, wondered that be had given his life in a nationalist struggle. But the struggle was by no means wholly nationalist, and his part in it was not inconsistent with bis earlier policy. In 1896 he had founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party, which established a paper called The Worker,’ Republic under his editorship. In 1897 this party organized an anti-Jubilee demonstration against Queen Victoria. In 1898 it was prominent in commemorating the Republican Insurrection of the United Irishmen. In 1899-1900 the party agitated against the Boer War, and joined the Republicans in establishing the Irish Transvaal committee, which organized an Irish Brigade to fight with the Boers against the British. Connolly was in America from 1902 to 1910. In 1910 he returned to Ireland and became organizer both for the Socialist Party and the Irish Transport Workers’ Union, which had been founded in Dublin by Jim Larkin in 1909.

Connolly’s work for socialism had therefore always been closely associated with the idea of an Irish republic and with the idea of a nationalist insurrection. In many ways his policy, and the evolution of the Irish working class movement as a whole, followed along the self-same lines which have developed in Britain. First isolated unions were formed in various trades: then a trade union congress was formed in 1894, a mere loose federation and purely industrial. The Socialist Party, formed two years later, had at first no connection with the trade union movement. Larkin, by his activities in both bodies beginning in 1907, and Connolly, becoming both a socialist and a trade union organizer in 1910, helped, no doubt, to hasten their inevitable union. So long ago as 1899 local labor organizations had run candidates for local elections, but their nominees had been absorbed into the capitalist parties. In 1911 a number of Irish Trades Councils secured seats for labor candidates on municipal councils, and at the Trades Union Congress in Galway a motion to establish a Parliamentary Labor Party was defeated by a narrow majority. In 1912 the same motion, moved by Connolly, who appeared in the congress for the first time, was carried by two to one. The Irish labor movement had become political and it had adopted parliamentarianism, because the political development of its socialist leaders had as yet reached no further. The socialists had captured the leadership, though not always the complete control, of the trade union movement by the time the transport workers, led by Larkin and Connolly, entered the trade union in 1910. The story of Connolly, the Irish Socialist Party, and the Irish Trade Union Congress is largely a repetition of the story of Keir Hardie, the I.L.P., and the British Trade Union Congress.

But it was the expectation of a Home Rule Parliament in Dublin which had provided the main impetus towards parliamentarianism in Ireland; and with the shelving of the Home Rule Act and the outbreak of war Connolly, and with him Irish labor, were driven back to rebellion. It is significant that in 1915 Connolly was publishing a paper called the Irish Republic. So it was that the Irish rebellion was the first revolution produced by the war- and to Connolly it was largely an economic rebellion, whatever it may have been to his colleagues.

Ireland was at first very far from unanimous in supporting the rebellion. Some of those who fought in it have told me that if, after the British government had shelled Dublin, it had simply turned the rebels adrift in O’Connell Street, they would have been stoned for having caused the ruin of the city and the loss of many lives. But by the execution of sixteen leaders the rebellion and those who had made it were sanctified for the mass of the Irish people, and above all James Connolly and his writings gained a wide and far-reaching influence.

Sinn Fein and Socialism

Nevertheless, it must not be thought that the nationalist movement has become socialist. Sinn Fein, which took small part in the rebellion, the Sinn Fein leaders who held aloof from it but afterwards became popular because the government deported them, have inherited the great nationalist rebel movement that arose from the blood of the martyrs. In the parliamentary election at which candidates were pledged not to go to Westminster, but to join in setting up an Irish Parliament (Dial Eireann), the Labor Party was told to stand aside lest it should split the vote, and it did so. Dial Eireann represents no new tendencies in social evolution. Arthur Griffith, who mainly controls it, is a narrow doctrinaire. His chief panacea for Irish troubles is the tariff wall. Ignoring the world development of capitalism, he argues that the British government is solely actuated by the desire to exterminate the Irish people.

Constance de Markievicz is the only member of the Cabinet of the Dial, and of the Sinn Fein Executive, who has been prominently associated with the labor movement. She joined the Liberty Hall workers in the 1913 lockout, and toiled early and late in the feeding center. She also joined the Citizen Army and organized boy scouts to fight for Ireland. As every one knows, she was condemned to death for her part in the rebellion. She is a woman in middle life, rather worn in appearance now, but as active as a girl, and exuberant in her enthusiasms. During her long imprisonment in England she was able to think and study. She came back to freedom, like many other prisoners, with a broadened outlook. She takes a keen interest in Russian communism and reads all she can about it. She refuses, as yet, to recognize the deep cleavage which exists, and must widen, between official Sinn Fein and the communist movement, but when the inevitable struggle between communism and capitalism comes, I think she will choose the side of communism.

Darral Figgis, another member of the Dial, has also communist tendencies, indeed theoretically I think he calls himself a supporter of the Bolshevist policy, but I think also that he is unlikely to take an active part in achieving the social revolution. The Sinn Fein attempt to achieve freedom for Ireland at the Peace Conference was in my opinion harmful, except from the superficial point of view of keeping the subject alive with fresh stunts. Nothing could be hoped for from the capitalist politicians who had engaged in the great struggle. It was bad tactics to lead the Irish people after a will-o-the-wisp, and to divert their attention from what they could do for themselves at home.

Labor is the strongest, indeed the only powerful force behind the movement for Irish independence. This was demonstrated when the threat of conscription came, and the one-day protest strike stopped the wheels of business and productive life in Ireland.

At Limerick

Again when Limerick was proclaimed a military area, and no one was allowed to enter the town without a permit, labor alone could cope with the situation. The military had drawn a circle round the town, and had drawn it so that all that part of the town which lay across the river was considered outside the town. Therefore workers living without the circle had to get permits to come in to work: workers living within the circle and going outside it to work, needed permits to come home. Therefore the workers downed tools and for two weeks all activities were suspended. The strike committee was called the Soviet. Shops were opened only for a short time each day and prices were lowered, at its bidding. Vehicles only drove through the streets by its permission, carrying a large notice to say so; newspapers were only allowed to appear on two days and only then if they printed a prominent notice that they were authorized by the committee. The cross-channel flyers and the trans-Atlantic flyers had to come up the little dark stairs of the strike committee’s office for permission to bring gasoline into the town. In the end the permits were withdrawn on the pretence of a concession to the American visitors, and though Limerick was still called a military area, the restrictions were not enforced.

But actually the strike had collapsed without achieving a decisive victory. It collapsed for lack of financial support. Official Sinn Fein gave no assistance. It was “considering” the question. The Irish Transport Workers’ Union gave $5,000. The Irish Labor Party gave $2,500. The Irish Clerks’ Union gave $1500. Branches of various unions gave small donations. In all less than $15,000 was received, and upwards of 80,000 people whose wages had stopped were to be fed! A limited amount of food was given by Sinn Fein farmers and Sinn Fein clubs in the country around the city, but this the strike committee was afraid to distribute without charge lest the shopkeepers should be offended and unite against the strike. The food was therefore sold at various centers, the proceeds being used for strike pay, but amounting to very little. Having no money to spend, masses of people could not buy food at any price.

The strike committee decided to print its own money; indeed the money was actually printed. A committee of influential persons agreed to interview the shopkeepers with an appeal to honor the strike committee’s money. But when the influential persons heard there was less than $1,500 in the bank, they refused to start out on the canvas. At the same time it was said that the priests were about to issue a manifesto against the strike and the priests have great influence in Ireland. It was rumored that trade was leaving the city and being diverted to other parts never to return. The strike committee in panic suddenly called off the strike. Many rebel spirits tore down the committee’s proclamations, but the return to work had begun and the strike could not stand.

During the strike a deputation from the Labor Party, including Tom L. Johnson, had visited Limerick to discuss the prospects. A general strike of all Ireland was considered, but the project fell through, because the Labor Party representatives insisted that such a strike could only be a demonstration lasting one or two days, and the Limerick strike committee would not pledge itself to carry on their strike after the general body of Irish labor had returned to work. Tom L. Johnson suggested that the city should be gradually evacuated by its inhabitants, being temporarily housed by comrades in the country. The Limerick Committee replied that this was impossible, as the military would sack the deserted town. There was much recrimination by those who knew little of the facts, as a result of the collapse of the strike. Many blamed the Limerick Committee. Many blamed the Labor Party. Sinn Fein with its big bourgeois membership had greater opportunities of raising money than had the labor movement; for the labor movement, reduced to bankruptcy in 1918 and again in 1916, has not been able to accumulate large reserves. But Sinn Fein does not seem to have been blamed for failing to support the Limerick protest, although the protest was a purely national one.

Though it failed to achieve a complete success, the Limerick strike was a wonderful demonstration of solidarity: nothing like it has been accomplished in Britain. Those who hoped that it might portend an important proletarian awakening feared to build too much on it, because, as the protest was a nationalist one, the bourgeoisie of Limerick had largely acquiesced in it.

But on the following May Day we saw that Irish labor, without any support from Sinn Fein, could organize a national demonstration strike which was practically complete throughout Ireland, and in which the manual workers were solid, and even clerks and civil servants joined. The red flag was declared illegal on that day, but everywhere it was flown.

Three Schools of Thought

In the Irish labor movement, as in that of other countries, three distinct schools of thought are beginning to make themselves felt, though they are less clearly defined, as yet, than we find them in Britain.

These are: (1) The old-fashioned nonsocialist reformists, determined to adhere to what the capitalists tell them is constitutional and anxious to avoid industrial action. (2) The mildly militant parliamentarians, who want reforms, even socialism, if they can get it without too much effort, who rely mainly on legislation but would use industrial action as a threat and a spur. (3) The industrial revolutionary socialists.

From my observation of Irish affairs I should say that many people active in the movement are not quite sure to which of these categories they belong: not having cleared their own ideas they float mentally hither and thither, supporting sometimes one policy, sometimes another. There are many people like that in Britain also.

The official policy of Irish labor is a little mixed. It is far in advance of, and much more militant than, the policy of official British labor. But that is at present inevitable, since on the railway bridge facing Liberty Hall (the labor headquarters) are stationed always those sinister block-houses with armed gunmen ready for action!

The Executive of the Irish Labor Party some time ago stated its position in regard to the Russian Soviet Republic in these terms:

“Irish labor utters its vehement protest against the capitalist outlawry of the Soviet Republic of Russia, and calls upon the workers under the governments sharing in this crime to compel the evacuation of the occupied territories of the Republic at the same time as it renews its welcome and congratulation to its Russian comrades, who for twelve months have exercised that political, social, and economic freedom towards which Irish workers, in common with their fellows in other lands, still strive and aspire.”

Nevertheless the Irish Labor Party, though it held meetings, did not join the demonstration strike proposed by the Italian workers for July 20th and 21st, 1919, in support of the Soviet Republics. Was Irish labor officially approached, or was it left to take its invitation through England?

Cooperation

There are also hopeful constructive tendencies in Ireland. A flourishing cooperative farm-produce store was left behind when the Limerick strike ended, and butter, potatoes, buttermilk, firewood, and other commodities continued coming into the city from the country on a permanent basis, and were sold below the usual price. Demands for increased wages and sectional strikes followed in trade after trade, and substantial increases were secured throughout the district.

In Dublin, the hotel and restaurant workers’ strike, which went on for many weeks, resulted in the opening of a cafe close to Liberty Hall, staffed by the employees of one of the first hotels. Some sort of cooperative industry seems now to arise from the ashes of every Irish strike.

George Russell, who has been preaching cooperation for many years, begins now to see a substantial beginning made in the realization of his long-cherished idea. Communism will not come in driblets without an upheaval, but these constructive efforts by the workers indicate a development in their power and solidarity.

The Socialist Review was the organ of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, and replaced The Intercollegiate Socialist magazine in 1919. The society, founded in 1905, was non-aligned but in the orbit of the Socialist Party and had an office for several years at the Rand School. It published the Intercollegiate Socialist monthly and The Socialist Review from 1919. Both journals are largely theoretically, but cover a range of topics wider than most of the party press of the time. At first dedicated to promoting socialism on campus, graduates, and among college alumni, the Society grew into the League for Industrial Democracy as it moved towards workers education. The Socialist Review became Labor Age in 1921.

PDF full issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Socialist_Review.pdf?id=L4dVAAAAYAAJ&output=pdf