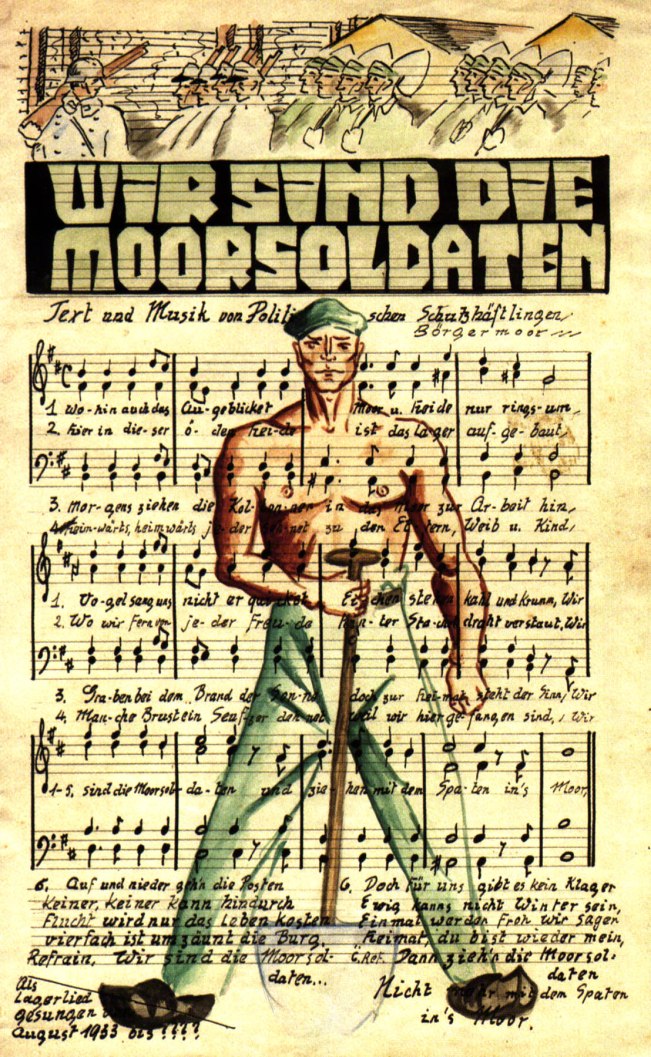

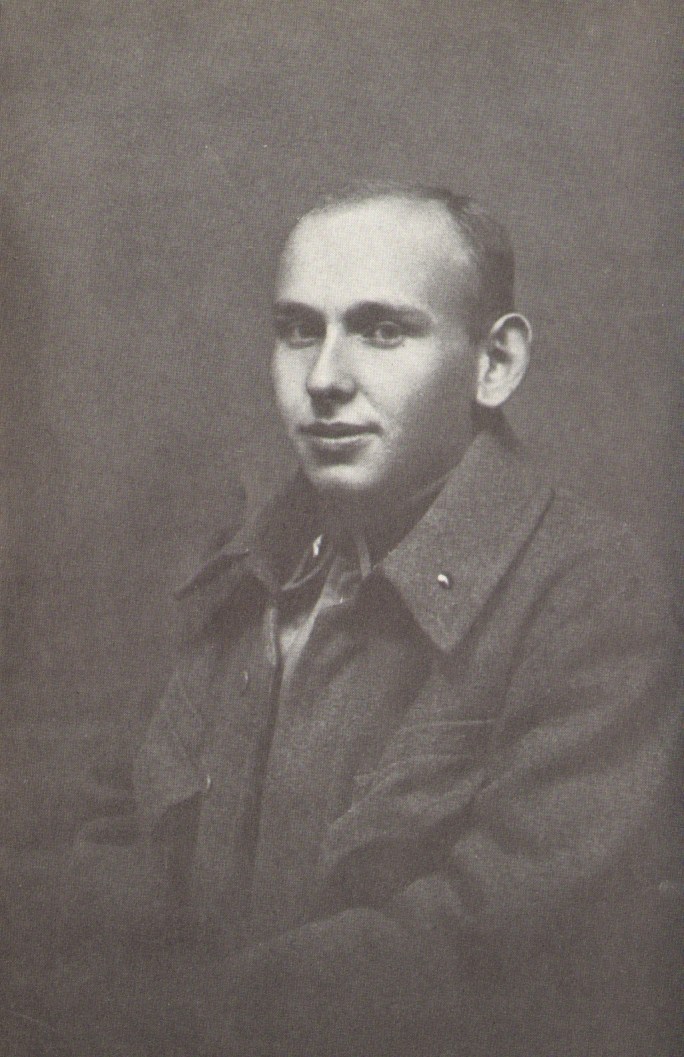

Hanns Eisler tells the story of the remarkable origins of an anthem of the Left, the song ‘Peat-Bog Soldiers’ for which he would adapt music.

‘Peat-Bog Soldiers’ by Hanns Eisler from New Masses. Vol. 14 No. 11. March 12, 1935.

IT IS deep twilight on the peat bogs. The prisoners of the Papenburg State Concentration Camp straighten up and shoulder their shovels. Another day of backbreaking toil done with. Under the sharp commands of the S.A. guards, the prisoners, begin to move, – back to the prison, singing Nazi military songs. The reluctant low-voiced tones contrast sharply with the words that are full of high-sounding, nationalist sentiments. The Nazis shriek for more spirit, for louder singing. But the long shuffling line scarcely responds. The singing is as inaudible as before. It is not their song. They feel no lift in these words.

And then one day, new words begin to appear in place of the old. The tune is the same, but now the words begin to have meaning. The prisoners have discovered a new method of guarded communication. At first the new song spreads slowly, almost imperceptibly- and like all spontaneous collective movements, it seems to spring from a dozen places at once. Then it gathers momentum and soon all the Papenburg inmates are singing the new words.

But even this is not enough. The new words begin to be improved upon. Some of the more advanced prisoners begin new texts and even new music. This new music springs from the 16th and 17th-century peasant uprisings, and the Thirty Years’ War, carried into the present by the young people’s movement of Germany and remembered by some of the Papenburg prisoners as more fitting for their needs.

Underground, hidden from the eyes and ears of the police guards, the new song is handed about from prisoner to prisoner. In stolen, dangerous moments, small groups collect and rehearse.

Then, suddenly, seemingly from nowhere, a new song bursts from the prisoners of Camp No. 1 (there are five camps at Papenburg) on the march. Immediately, the other camps take it up. The music is smuggled to the other barracks and before the Nazi guards can realize what has happened, all of Papenburg prison is singing the Peat Bog Soldiers. Many storm troopers, affected by the song, take copies home with them. The police scrutinize the Peat-Bog Soldiers in order to find communist or socialist meaning in it, but on the surface the words are harmless.

Far and wide to the horizon

Heath and bog are everywhere.

Not a bird sings out to cheer us,

Knotted oak-trees, bald and bare.

We are the Peat-Bog soldiers.

We march with our spades to the bog.

Where the heath is bare and barren

Stands our lonely camping ground…

In the morning go the squadrons

To the bog to shovel peat-

Longing for home we labor

In the blinding summer heat…

But for us there’s no complaining.

Winter cannot last all year.

One day we shall cry, rejoicing:

“Home again! At last we’re here!”

Then will the peat-bog soldiers cease

To march with their spades to the bog…

So splendid, so stirring is the new song, that even the population round about begins to collect on the sidelines in order to hear the new prisoners’ song. Many storm troopers are so affected that they are finally replaced by the more reliable police troops. Eventually, although nothing political can be found in the song, it is regarded as dangerous and prohibited by the commander of the camp.

But this song cannot be eradicated. It has already struck: roots in the German people outside the camp. Workers of many other countries are fast becoming familiar with it. It is a revolutionary song, created spontaneously by the workers out of their very oppression and fascist persecution.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v14n11-mar-12-1935-NM.pdf