Edward Newhouse reports on the 1937 strike of 6,000 Hollywood craft and studio workers, the largest in the film industry that decade. The limits and corruption of the A.F. of L.’s approach in the face of the C.I.O.’s challenge is explored, as is as another, unofficial, reason behind the strike- the organized, large-scale, and open, sexual exploitation of women ‘extras.’

‘Hollywood on Strike’ by Edward Newhouse from the New Masses. Vol. 23 No. 8. May 18, 1937.

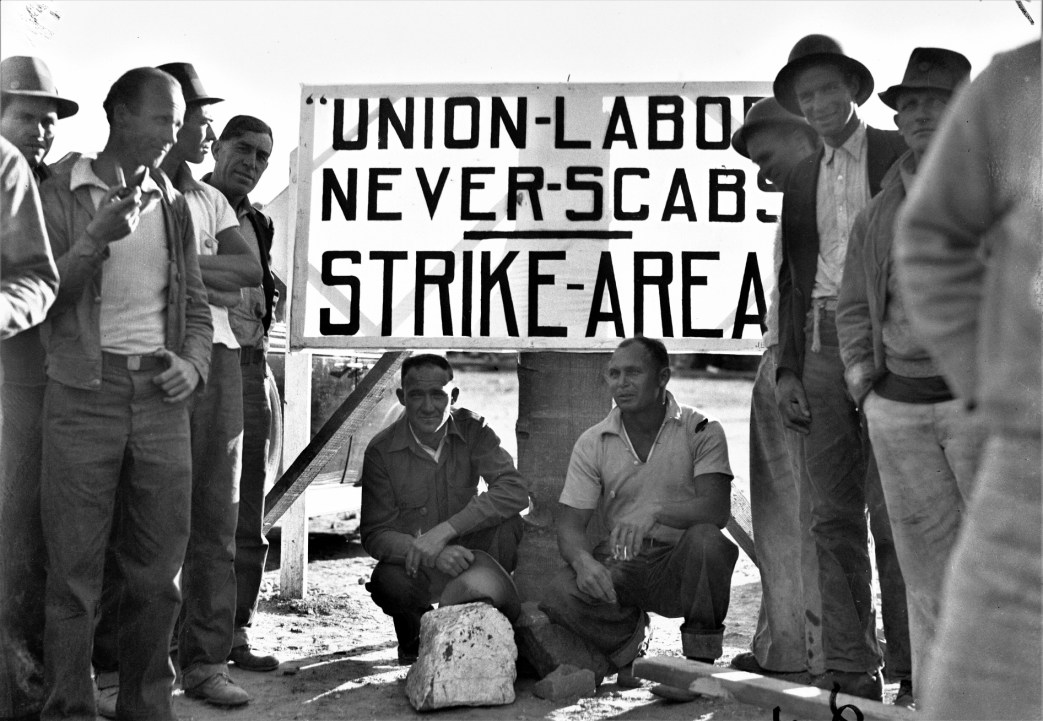

The picket lines of the technicians signify not only bad conditions, but are revealing on the craft-union question

HOLLYWOOD.- “I have a lot of reasons for being here,” said one of the sound technicians on the picket line in front of the Warner Bros. studio at Burbank. “Listen carefully and I’ll explain some of them. Last night my girl gets a call to report at the Hal Roach studios for work in an evening gown. She’s an extra. So she meets a bunch of the girls and they’re piled into a bus. There some of the other girls tell her they’re really going to a party out at the Hal Roach ranch, two hundred and fifty of them at $7.50 apiece. The M.G.M. convention was in town and the boys were going to have themselves a stag. So they get out there and the party’s in full swing.

“Plenty of champagne and music and Mexican entertainers. Plenty of Scotch and rough stuff. Now most of those girls are over twenty-one, and somebody who doesn’t know the set-up here would think they knew better. But they’re picture girls and they know what it means not to answer a call, even if it doesn’t come through Central Casting. So there’s girls all over the place, girls drunk and girls crying, fighting off guys or going off into rooms, and pretty soon my girl gets sick of it and phones me to pick her up. So I go out there and force my way in, and a more disgraceful scene I never hope to see. People sprawled all over, clutching bottles. I couldn’t begin to tell you about the place. They must have blown in all of $20,000 on that party, and all the big shots there, Hal Roach and Joe Cohen and the rest. So on my way out I hit a guy who said something dirty about the strike. My girl kept crying all the way home.

“If only to fight people like that, I’d be out here. But there’s other reasons. Three years ago I was making $150 a week along with the rest of the skilled sound technicians. Along comes a jurisdictional dispute between the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, and we get the old tossing around, and after the razzle-dazzle is over we’re making $40 a week and working unlimited hours. I’m not picketing here because somebody told me to.”

To DATE, craft unionism has hamstrung every attempt to organize America’s fourth largest industry. Five international unions, the musicians, teamsters, carpenters, electricians, and the I.A.T.S.E.-operate under basic agreement with producers, but they have fought among themselves and with unions which should have been their close allies.

The I.A.T.S.E. is the International Alliance for Theatrical and Stage Employees. Its initials are locally pronounced Yazi or Nazi. It’s a mushroom grouping of craft-union locals, ostensibly on the industrial-union principle, but run by the corrupt Brown mob with an abandon that would have done honor to Umbrella Mike in his palmiest days. They started as a paper organization, then agreed with the producers on a closed-shop pact which stampeded the workers into signing.

[The author refers to the group of I.A.T.S.E. leaders headed by George A. Brown, who was appointed in October 1936 a member of the Executive Committee of the A.F. of L. replacing David Dubinsky of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. At this time, the I.A.T.S.E. had 5500 members, which made it the biggest A.F. of L. union in the film industry. The present strike breaking activities of the I.A.T.S.E. are not unprecedented in the history of this union. Some five years ago it signed an agreement with the movie producers providing that first cameramen should not join the Yazis, but should remain in the American Society of Cinematographers for the duration of their five-year contract. This achieved two purposes for the producers: it divided the skilled technicians into two rival camps, and kept the first cameramen in what is to all intents and purposes a company union. The practical advantages of this arrangement for the producers, as well as the effect of George A. Brown’s policies, became abundantly clear in 1933. The sound men, organized in the I.A.T.S.E., went on strike, and the first cameramen, organized in the Society of Cinematographers, were used to break that strike. -The Editors.]

There hasn’t been a membership meeting since. Then out of a clear sky, Brown slaps a two-percent payroll assessment on all members over and above the regular dues, death assessments, etc. The other day one of a group of reporters asked an official what the Yazis did with this money, the men would like to know. And the officials said, “What’s the difference, what good would it be for them to know?” Nobody was shocked when the local papers ran this.

The Yazis could no more be expected to lead a fight against prevailing conditions than Hutcheson of the carpenters or Tobin of the teamsters, both of whom are backing William Green’s attempt to break the current strike. The plight of the extras has been described often enough, but conditions among other studio workers are almost as bad. Whether you’re a plumber, scenic artist, molder, or costumer, you’re on tap twenty-four hours a day and you better hug the telephone or someone else will get the call. You can be snatched to work on location for a couple of hours, then not see a paycheck for weeks. And Harry Cohen won’t underwrite your telephone bills, either.

Matters came to a head when the Brown gang made an attempt to chisel the painters’ union away from the Painters’ International, no less. The movement for genuine industrial unionism got irrevocably under way in the studios, and the new Federated Motion Picture Crafts was formed. The call for the present strike was issued on May Day by Charles Lessing, and it pulled eleven unions out of the ten major studios. Production is still under way, since the need for the type of work performed by these 6000 strikers will not assert itself decisively for a while. Picket lines have to patrol an unnaturally large number of entrances and areas. But they’re solid and clicking.

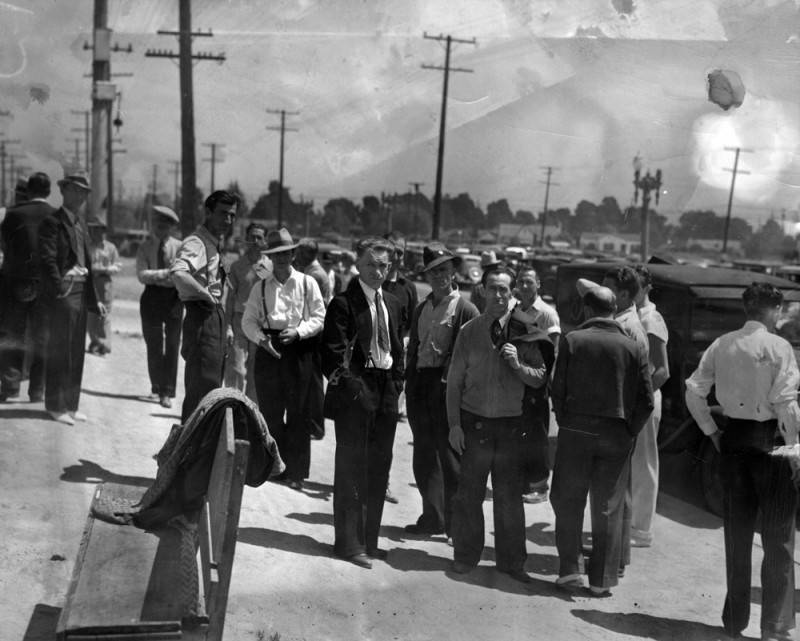

Naturally, Tobin, chieftain of the carpenters’ union, and William Green, A.F. of L. president, and the I.A.T.S.E. swung into action. Green wired to say he thought the strike was “unfortunate.” The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers office sent a telegram instructing the Hollywood officials of their union immediately to expel any member who refuses to walk through the picket lines. A similar telegram came from the office of the teamsters’ union. Then other telegrams came through dozens of local organizations, a donation to the strikers from the Los Angeles Newspaper Guild, $500 from the Screen Actors’ Guild, support from Harry Bridges of the I.L.A. Then came assurance of full support from John Brophy of the C.I.O., and that brought down the house in a five-minute ovation at the strikers’ mass meeting. WITHOUT EXCEPTION, eighteen pickets I chose at random expressed themselves in favor of joining up with the C.I.O. And the Federated Motion Picture Crafts must do this if it is to survive.

Even Charles Lessing, who told me he favored industrial unionism in principle but thought the C.I.O. premature, has since stated, cautiously enough, that he would “accept aid from those who offered it.” Certainly he did not mean the executive board of the Los Angeles Central Trades Council, whose head, J. W. Buzzell, rushed into the fray with a preposterous offer for settlement immediately accepted by the producers. Buzzell proposed (1) that the workers go back on the job and (2) that they negotiate demands afterward.

Not even the NEW MASSES can undertake to print the precise wording of Lessing’s answer. As far as the newspapers were concerned, the Federation’s reply placed the workers in the position of refusing to arbitrate. But an acceptance of Buzzell’s proposals would have been worse than the Yazis’ current tactic of giving free union cards to strikebreakers.

At this point, it must be said that the rank-and-file movement for democratic control in the I.A.T.S.E. is daily growing, and has already crystallized around the “white rats” group, inappropriately so designated.

At this writing, a great deal but not everything, as has been supposed, depends on the conduct of the Screen Actors’ Guild. Individual actors and actresses, such as Elissa Landi, Luise Rainer, Gale Sondergaard, and Lionel Stander have already come out publicly in support of the film strikers, and the gift of $500 to the strike fund was official.

By the time this appears, more decisive action will have been taken on the hitherto equivocal position of the Guild. That this position has been hesitant and temporizing in the important first days of the strike can only be explained on the basis of the Guild’s varied composition and curious constitution. Here is the only incorporated labor union in America. Its membership is divided into junior and senior groups, i.e., those who make less or more than $250 a week. The junior group is militant but virtually disfranchised. Any of their proposals or resolutions, unanimous though they might be, can be vetoed by the seniors. Just like that. Since its formation, the Guild’s executive board, composed largely of conservatives, has chosen to maneuver with the A.F. of L. leaders who could have forced recognition of the Guild by the producers with a single strike.

The lesson of the longshoremen who refused to work with non-Guild actors seems to have been lost on the Guild’s hoard. It hastened to enter into relations with the reactionary Buzzell machine in the Central Trades Council, but failed in its clear duty to join the Federated Motion Picture Crafts on the day of its formation.

Unfortunately, this is being written before the annual membership meeting of the Guild, where participation in the strike will finally be considered. Right now, however, it is clear that sentiment for such participation is strong even among the seniors. In response to his splendid speech at a special Guild meeting, Lionel Stander has received a telegram that is more than equivalent to the year’s Academy award: “May the undersigned organizations express their deep appreciation for your unsurpassable stand in their behalf at the meeting of the Guild. Trade unionists will never forget you nor forsake you. Motion Picture Painters, Make-Up Artists, Scenic Artists, Utility Workers, Stationary Engineers; Machinists, Cooks and Waiters, Plumbers, Molders, Boiler Makers and Welders, Costumers, Federated Motion Picture Crafts.”

Clearly it is up to every union man and friend of organized labor to boycott all productions of the ten struck studios, M.G.M., Paramount, Warner’s, and the rest, until satisfactory settlement has been made. The loss in revenue caused by every union man’s decision to miss but a single show would make Messrs. Casey, Schenck, and Mannix much friendlier at the green table.

[At its annual meeting on Sunday, the Screen Actors’ Guild disassociated itself from the strike in order to obtain a closed shop for itself. In doing so, it lined up with the I.A.T.S.E., whose representative spoke from the platform. This action has compelled thousands of rank and filers, sympathetic to the strike, to walk through the established picket lines. Progressives are hoping that the Screen Actors’ Guild, having won a closed shop for itself, will now help the strikers win one, too.-THE EDITORS.]

Meantime, Harry Bridges’s longshoremen are picketing Grauman’s Chinese Theatre; American Student Union members take regular turns in the lines around the studios; and local motion picture houses are reporting a drop in business as high as 60 percent. Win or lose, this is a strike for industrial unionism, and that’s one thing out of which Sam Goldwyn can’t buy his way. It’s all over Los Angeles now, and in his own words, “It’s colossal, but it’ll improve.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v23n08-%5b09%5d-may-18-1937-NM.pdf