‘The ‘No Strike’ Policy in the South’ by A.J. Muste from Labor Age. Vol. 19 No. 5. May, 1930.

THE time for a final appraisal of the A. F. of L.’s campaign in the South, particularly in the textile industry has obviously not arrived. However, it is now fully six months since the Toronto convention resolved on this campaign and four months since it was launched. A preliminary appraisal of the main lines that have been laid down for the campaign would seem therefore to be in order. If it is proceeding on fundamentally sound lines, we can afford to be patient in waiting for tangible results in a situation obviously fraught with the greatest difficulty, especially in a period of depression like the present. If, however, the line laid down is inherently unsound, then it is better that that fact should be faced at once, so that no false hopes may be raised and so, if possible, a better road may be opened up.

The crux of the situation is unquestionably to be found in the so-called “No Strike Policy” followed by the A. F. of L. and openly announced by the United Textile Workers. “No strikes,” according to a recent press dispatch, “is the watchword of the U. T. W. in its 1930 campaign for the unionization of the Southern cotton mills.” According to the first vice-president of the union the policy is now meeting its first test in the Dan River mills in Danville, Va., where an effort is being made to induce the management to meet the union half-way in rescinding a recent IO per cent wage cut, to accept its aid in labor stabilization, and to establish contractual relations. All this is in line with the policy enunciated sometime previously by Pres. McMahon himself, viz., that the severe pressure of unemployment in New England and Philadelphia has cut down the union’s reserve funds so that it cannot back up Southern strikes with adequate relief, that in any case the union has already spent a million or more in the South over a period of years and that Southern workers must now show loyalty to the organization in dues payment before they can expect much more in the way of relief.

Obviously this raises very urgent and fundamental questions. What is to be said of such a policy? Is it a wise and sound, though cautious, approach to a very tough situation? Or is it fundamentally unsound and certain to produce no lasting and important results? Is it, perhaps, a cowardly betrayal of a group of workers, a confession of utter weakness on the part of the official Labor Movement?

Before discussing the wisdom and promise of the policy itself, a word should be said about the wisdom of announcing the policy so openly, propagandizing for it so insistently as is being done.

Poor Tactics

This seems to the present writer to be a serious mistake. The psychology of it is very bad. In the first place, under the present circumstances and in view of the form which the announcement takes, it can only be interpreted as a confession of weakness. The world, including the employer, is bound to understand it as such. A union must often of course strive to make clear that it is not going out of its way to seek, much less to make, trouble. There are times when it is in no position to take on additional burdens, and by one means or another its enemies are likely to know the actual state of affairs about as well as its friends. There are limits to the big talk and bluff it can engage in. But unless all hope of being able to accomplish anything has been abandoned, an organization must put up some kind of front, make some show of determination, of courage, of hope, of readiness to do battle if need be. Even if there is no hope whatever, it is better to bite one’s lips and keep still about it than to proclaim one’s own weakness. It is conceivable that it might do some good to assure people that the union is peacefully disposed, but it can do no good to assure them that it is weak. This is the clear import of much that is being said and done in connection with the Southern textile campaign, and it is bound to have a bad psychological effect on Southern employers.

The effect of the announcement on the workers is also on the whole bad. The great essential is that they should be roused to action, to the willingness to do battle for themselves, even though they must in specific instances be advised to delay a strike. The general “No Strike” announcement will not have this desired effect.

Likewise, the impression bound to be made on the public is bad. Much ado is made over the announcement that the union is now peaceful, it is not going to have strikes. The inference is that strikes and trouble in the past have been caused by the union, by outside agitators, as the saying goes.

That is of course a falsehood. Strikes and trouble were caused by the intolerable and unjust conditions under which people worked, by the refusal of employers to do anything adequate to remedy evils, and by the fact that every peaceful move to remedy conditions on the part of the workers was met by discharges by the employers and by unfairness and brutality on the part of courts, police, militia and mobs.

Why then, permit the inference that union is responsible for trouble? Why permit the inference that now, though the fundamental evils remain, the union can adopt a new policy, can resolve away strikes and industrial unrest? This is bad education for the public generally. It is giving away the case to enemies of unionism, and doing it without any reason for it.

Insulting Southern Strikers

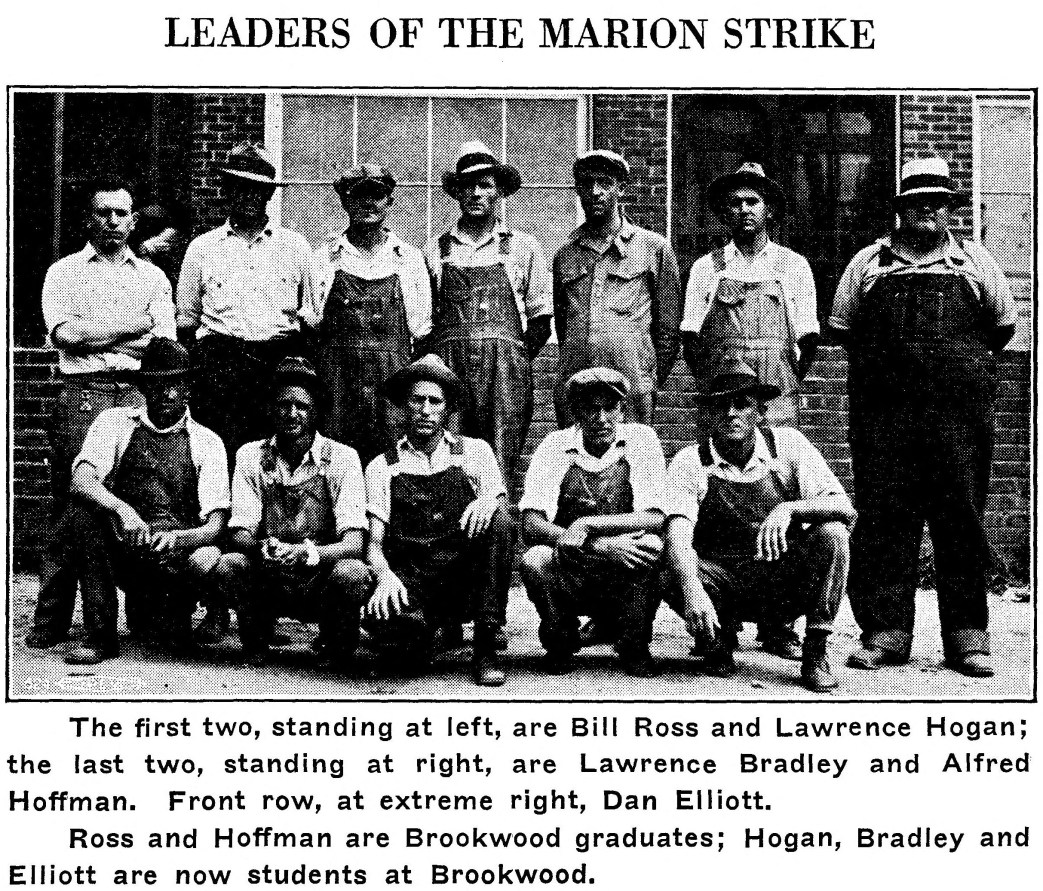

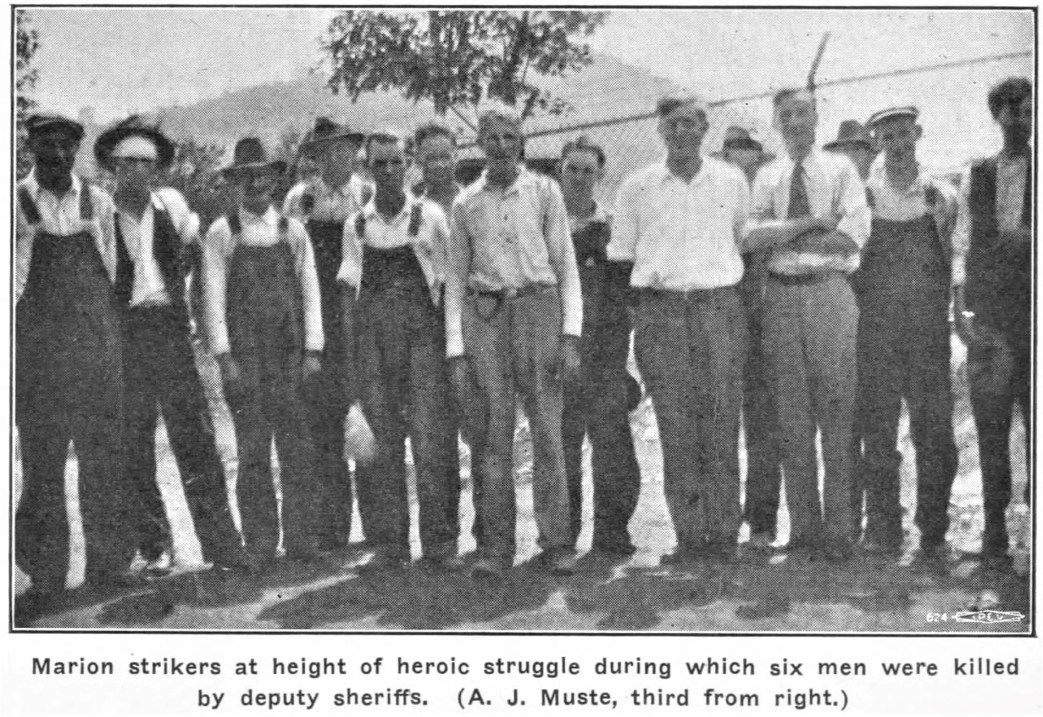

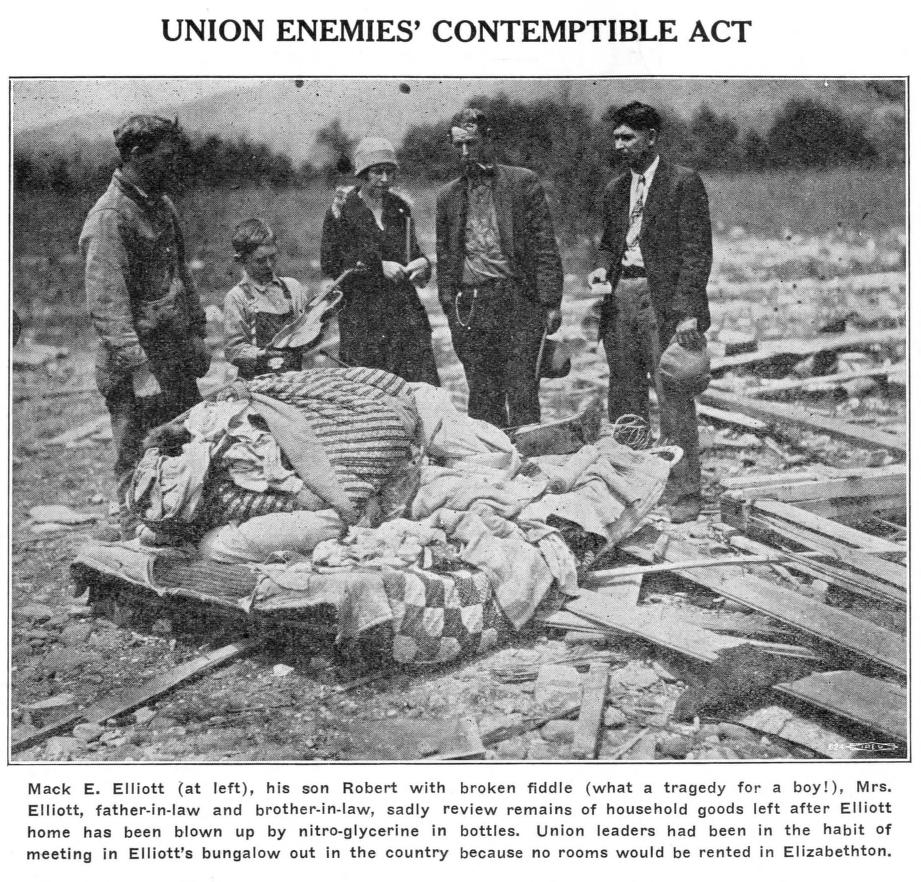

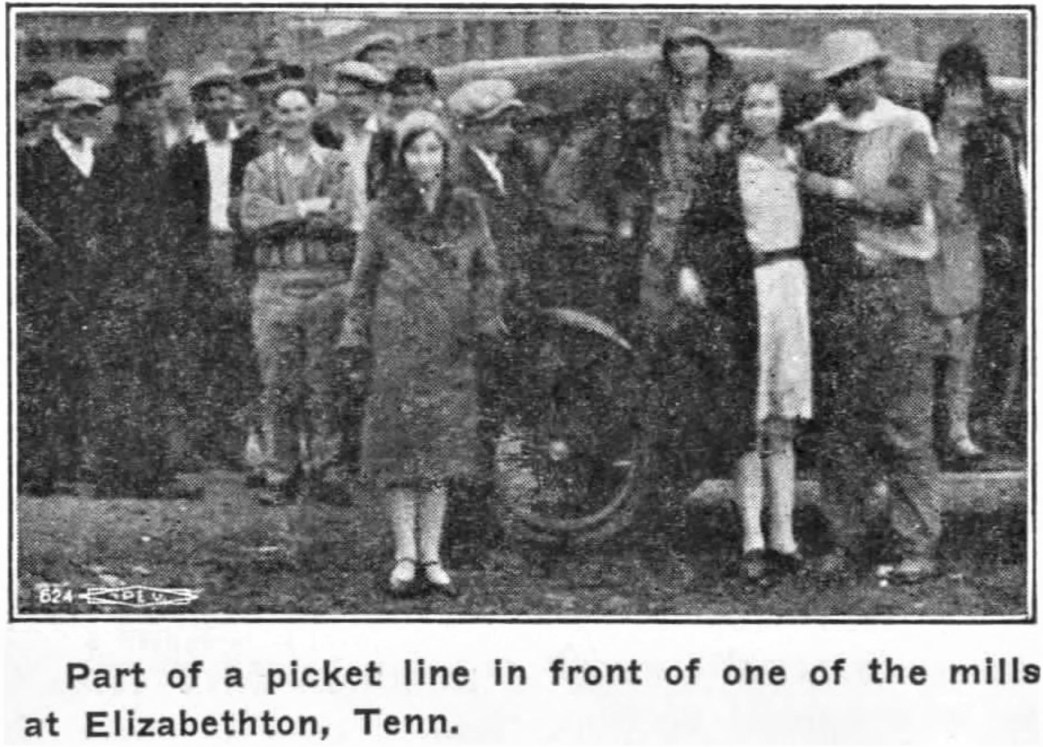

Furthermore, much of the propaganda, intentionally or unintentionally, does a grave wrong to the men and women who in all periods and all sorts of places, and recently in the South, in Elizabethton, Gastonia, Ware Shoals and Marion have battled and suffered for the cause of unionism. All along the inference is that they were the cause and not the victims of trouble. The most flagrant instance of this repudiating and insulting of Southern workers who have borne the brunt of the battle was Pres. Green’s statement in his Richmond speech to the effect that if the A. F. of L. had been in Marion last October there would have been no massacre there. His explanation, when he was questioned, that he meant there would have been no trouble if the A. F. of L. had been recognized and an agreement had been in effect, seems lame. But even if it is accepted, the fact remains that nothing has ever been done to correct the impression made; rather there is a persistent attempt to disassociate the A. F. of L. from connection with any “unpleasant episode,” make it appear as “harmless as a dove.” As I have said, this is an outrageous insult upon the strikers and martyrs of the South. Nor is any life left in an organization or movement when it seeks to forget instead of to celebrate its heroes and martyrs.

What shall be said of the “No Strike Policy’ in itself, as distinct from the proclamation of it?

It is of course not startlingly new. It is just another form of the “peace policy” which has marked the official A. F. of L. program since the death of Gompers, and which attempts to organize workers by appealing to their employers and seeking to persuade them that having a trade union would be “good for the business,” rather than appealing to the workers to organize on the ground that it is only by solidarity and struggle that they can protect and advance their material and spiritual interests. LABOR AGE has frequently stated its opinion of this approach and we need not dwell on it at length here. The policy assumes (unconsciously perhaps) that there is nothing very serious for workers and employers to struggle about; but if that is true then of course no trade union is necessary and both employers and employees will be just as well or better content with company unions or an open-shop.

An effort was made to organize the automobile industry in this way and it failed ingloriously. The policy was pursued in Elizabethton after the settlement last year which made the personnel manager of the company the arbitrator in cases of alleged discrimination against union members and former strikers. It did not save the unions or the rayon workers there from any other strike this spring: — and there is now practically nothing in the way of organization left after all the effort and suffering. The policy did not prevent a 10 per cent wage cut in Danville. There is no case on record where the policy has scored a success, though the willingness to “cooperate” may of course be a factor in securing an agreement where organized power or the serious threat of it exists. None of the present A. F. of L. unions was built by this policy. There is no reason to suppose that it will work in the South.

In the Southern textile field at present there are two types of situations. On the one hand, there are the mills which are “paying” little or not at all, faced with keen and cut-throat competition, operating at relatively high cost. In most cases such mills are owned or managed by the conventional employer, conservative, fearful of unions or hostile to them, not too far-sighted, with little social vision. Ask any intelligent and educated man in the textile field—employer, I mean —and he will tell you that for shortsightedness and stupidity these men are not to be matched in any other industry.

Dodging a Union Headache

Now what is the effect of the present union campaign upon them? The answer is that it is exactly nothing. These people have enough headaches as it is and are not going to be bothered with a union headache in addition if they can avoid it, and avoid it they can if the union confines itself to peaceful arguing with them. The union cannot possibly argue any more persuasively than their fellow employers have already done. These men, as already said, have no social vision and they certainly are not going to be won to accepting unionism for what it may do for the general good of the South in ten or even five years from now.

On the other hand, there are a number of concerns which are doing well. In some instances this may be due to luck, in others to good management. Among these concerns will be found some managers who know the world in which they live and have social vision, though many of them are just the usual hard-boiled, successful business men. The latter is not going to accept unionism unless he has to, and he does not have to under present conditions of over-expansion, surplus labor, etc.; at least not at the hands of a union which is bound not to fight. That leaves the few outstanding men who are both successful practical managers and possessed of wide knowledge and social vision. Will not these men, at least, welcome unionism, indirectly even urge their people to join the A. F. of L.?

We have talked with a couple of such men, but we flatter ourselves that we should have known the answer even without that. These people are where they are, because in the competitive struggle they have managed to keep one or more jumps ahead of the others. Therefore they are “sitting pretty’’—also as regards their labor relations. They can afford to keep up the houses in their mill villages, to pay somewhat better wages, and so on, and they do. The result is that they can have the pick of the labor supply, which gives them another little edge, and their workers are relatively satisfied. If they do begin to grumble, the boss can point to plenty of other mills where they can do worse “if you don’t like it here.” Now just as these men keep a jump ahead of their competitors, they are confident that they can keep a jump ahead of the union too. They may even say that the A. F. of L. is perfectly welcome to come in and try to organize their workers, for they are confident that as things stand the attempt would fail. In the case even of the best of these men, their vision of the future does not include industry with strong unionism; their picture is that of the General Electric, the utility corporations, Ford, the steel trust—the new capitalism, rich and powerful and intelligent enough to give the workers many concessions and so keep them immune from unionism. Only a hopeless fool will believe that these men can be argued or coaxed into organizing their employees for the U. T. W. They are supreme realists who will deal with their organized employees when they have to, but who will never deliberately, or in a fit of absent-mindedness, buy a headache for themselves by becoming union organizers or patrons.

Progressives have contended from the beginning that the Southern textile industry can be organized only if there is a well-planned, large-scale campaign; if the movement will go down into its pockets for the campaign; if strikes are waged or threatened over a sufficiently wide front to make employers realize that they must reckon with the union and so make the state hesitate to spend thousands of dollars for soldiers to break up strikes; if the soul of the Southern workers is roused to another battle for freedom, self-respect and justice. It may be that even so the odds would be too great. But it would mean something to all concerned to lose in such an effort, while anything else is child’s play, would be. comic if it were not such a tragic mockery of the Southern workers and of all those elements in the South who would like to see a genuine democracy developed there.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v19n05-May-1930-Labor-Age.pdf