Phoebe Brand was a top stage actress of the 1930s and a member of the Group Theatre with whom she appeared in work by Brecht, Clifford Odets, and Kurt Weill. Named personally by Elia Kazan as a Communists before the House Un-American Activities Committee, she and her husband Morris Carnovsky were blacklisted and did not perform for over a decade. Like many other blacklisted actors, they turned to teaching. In later life she was responsible for New York’s Theater in the Street program bringing plays to the city’s working class neighborhoods in both English and Spanish. She lived until 2004 and 96 years old, remaining active for much of her long life.

‘Phoebe Brand, “Actors Must be Good Trade Unionists”‘ by Jean Lyon from Women Today. Vol. 1 No. 10. January, 1937.

You Can’t Eat Glamour! Phoebe Brand thinks the stage is exciting-but actors must be good trade unionists if they want the theater to progress.

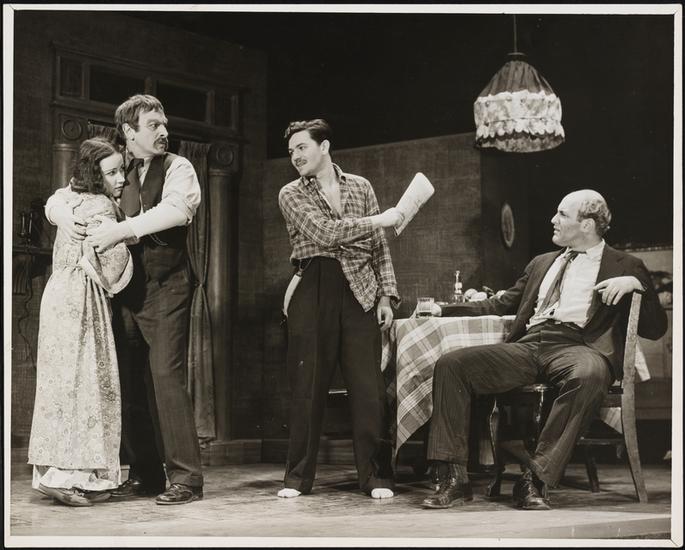

SHE HAS BEEN known most recently on Broadway as Johnny Johnson’s girl, Minny Belle, the girl who sent the peace-loving Johnny off to the war. She has been through enough war hysteria, night after night, to know something about what war is made of.

She was Florrie, in “Waiting for Lefty” -a shop girl, with a taxi driving sweetheart, who couldn’t get married and have her home and her baby because there wasn’t enough money. She went through enough then, night after night, to know something about what strikes are made of.

Backstage she is Phoebe Brand- young, dark-haired, winsome, one of the Group Theatre’s outstanding actresses- and she knows plenty about what acting is made of.

“It’s made of work,” she said to THE WOMAN TODAY. “Actors are workers just like anyone else who works for a living.”

Acting is made of glamour too, she thinks. But you can’t eat glamour. It may be that the glamour of the stage is what gets you into acting, and it may be the glamour that has kept so many actors in the business despite poor pay and poor working conditions.

“But the glamour,” Phoebe Brand said, “doesn’t make the actor feel any differently about his need to earn a decent living. I don’t see any reason why you shouldn’t eat and have glamour too.” She thinks the stage is exciting. Glamorous, if you will. But she thinks that actors have to be pretty good trade unionists, if they want the theater to progress.

“Even though I do think it’s a glamorous profession,” she said, “that doesn’t make me feel any differently about the importance of working through Equity, which is our trade union, for fairer wages and better working standards.” SHE HERSELF is still stage struck. She admits it, with a smile which puckers up her bright black eyes, “I still stare like a high school kid when I see some actor I’ve admired for a long time,” she said. “Even now, after I’ve met so many of them, I can’t help myself.” Elisabeth Bergner can practically put Phoebe Brand into a trance. She thinks she’s just about the best actress there is. She calls her “Bergner”- which, from another actress, is a tribute.

And the movies? “I go whenever I get a chance. I’m crazy about them. I’m afraid I like them good or bad. I don’t feel that way about the stage. A play must be good. But somehow the movies all seem pretty marvelous to me. I don’t see how the actors make themselves so real, working under the conditions that they have. I would consider it unbearable-those hot lights, and going over and over the same line for hours.” She shuddered. “I wouldn’t want to be in the movies. But I do admire the actors who are in them.”

As she talks about the movies and the stage stars, Miss Brand does give one the feeling that she thinks of herself as just a plain girl in her twenties. The fact that Phoebe Brand is also the name of a stage star doesn’t seem to have affected her in the least. She talks like any other girl with a job.

Her rise to leading roles has been partly due to her interest in the progressive movements in the theater. It has been through the Group Theatre, the permanent acting company formed in 1931, that she has done her best work. She was one of the original forward-looking young actors who formed the Group Theatre. Her work since she joined it has gained steady recognition.

Hers is a typical actress’s story. “I can’t remember when I didn’t want to be an actress,” she said. Four years after she was born in Syracuse, New York, she was taken to the theatre. “I saw Maude Adams in ‘Peter Pan,’ and Marguerite Clark in ‘Snow White,’ when I was very young. And I think I have wanted to be an actress ever since then.” In high school she tried out for the school dramatics, but was never given a part. “They didn’t think I was good enough,” she explained very solemnly.

But she was determined to try Broadway. She had been taking music lessons, with her mother’s encouragement, and her music teacher wanted her to train for opera. Miss Brand, being a single-minded young woman, wanted to act. She had to sing her way to the stage, to be sure. But she never once let the thought of opera get in the way of her ambition to become an actress.

Her first stage job was given to her because of her singing voice. She tells it now a little shamefacedly. It was as a chorus girl in the Winthrop Ames’ Gilbert and Sullivan company. Later she went to the Theatre Guild, again in a singing part.

The Theatre Guild gave her first speaking part, in “Elizabeth the Queen.” “It was a small part,” Miss Brand explained, “but it seemed enormous to me.”

All this time she had been going through the usual throes between jobs-though she considers herself to have been unusually lucky in having jobs that pretty much fitted in one right after the other. “But in those days, you know,” Miss Brand said, “we were paid nothing for rehearsals.”

“Actors,” she said with a hint of indignation in her voice, “are the only workers I know of who were willing to work for four weeks before every new job without pay. It’s incredible. But we did it. That’s all changed now, thanks to Equity,” she added.

Phoebe Brand had seen enough of Broadway and its hardships to feel that better things had to come if the theater, which meant so much to her, was to flourish. So when talk of the formation of a group which would be a permanent acting company began seeping through the stage doors, Miss Brand pricked up her ears.

It sounded like the sort of thing she believed in. There were to be no wide differentiations in pay between stars and other actors. It would be a year around job for those in the company. The plays that were to be put on, she felt, would be plays that had something to do with the world we live in.

She applied for membership in the company when it was first organized. “And I was chosen,” she said proudly.

She thinks more such groups are needed if the theater is to progress.

She became, too, at the same time, more interested in Equity, which she began to realize could get for her and for others in her profession some of the rights they felt they should have. “I think it is very important for every actor,” she said, “to be actively interested in his trade union, and to work through an organized group for better conditions in the theatre.” She has seen Equity bring pay for rehearsals, and higher minimum wages for her own profession during her own young acting life. She knows that actors, just like other workers, have to be organized.

Some of the consciousness she has of the importance of an organization of workers in every field has come through some of the plays in which she has acted. She says that Clifford Odets’ plays are the most thrilling. “They are swell to play in,” she said. “The characters are so rich. And,” she added, “they’re very convincing.”

In “Johnny Johnson,” by Paul Green, with music by Kurt Weil, Phoebe Brand has had to grow old on the stage for the first time in her life. All in five minutes she must change from a girl of twenty to a woman of forty.

“I have to try to feel the way I would feel if I were forty,” she explained. “Of course I watched women of forty, for a while, to see how they looked and acted. But we don’t believe that you can act through mimicry. You must feel the part inside you. The parts you take have to be you. You try to think how you would feel if you were that person, until you actually do become that person.”

Perhaps that is one reason Phoebe Brand feels so strongly against war and is so convinced that workers must unite in their efforts to win their rights. She has had to play the parts of people who have been through needless wars, and who have been on strike for their rights. And she knows how they feel.

What’s more, she is an actress who works at her job. And even if it is glamourous, it makes her a worker who has to eat on what she earns.

The Working Woman, ‘A Paper for Working Women, Farm Women, and Working-Class Housewives,’ was first published monthly by the Communist Party USA Central Committee Women’s Department from 1929 to 1935, continuing until 1937. It was the first official English-language paper of a Socialist or Communist Party specifically for women (there had been many independent such papers). At first a newspaper and very much an exponent of ‘Third Period’ politics, it played particular attention to Black women, long invisible in the left press. In addition, the magazine covered home-life, women’s health and women’s history, trade union and unemployment struggles, Party activities, as well poems and short stories. The newspaper became a magazine in 1933, and in late 1935 it was folded into The Woman Today which sought to compete with bourgeois women’s magazines in the Popular Front era. The Woman today published until 1937. During its run editors included Isobel Walker Soule, Elinor Curtis, and Margaret Cowl among others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/wt/v1n10-jan-1937-women-today.pdf