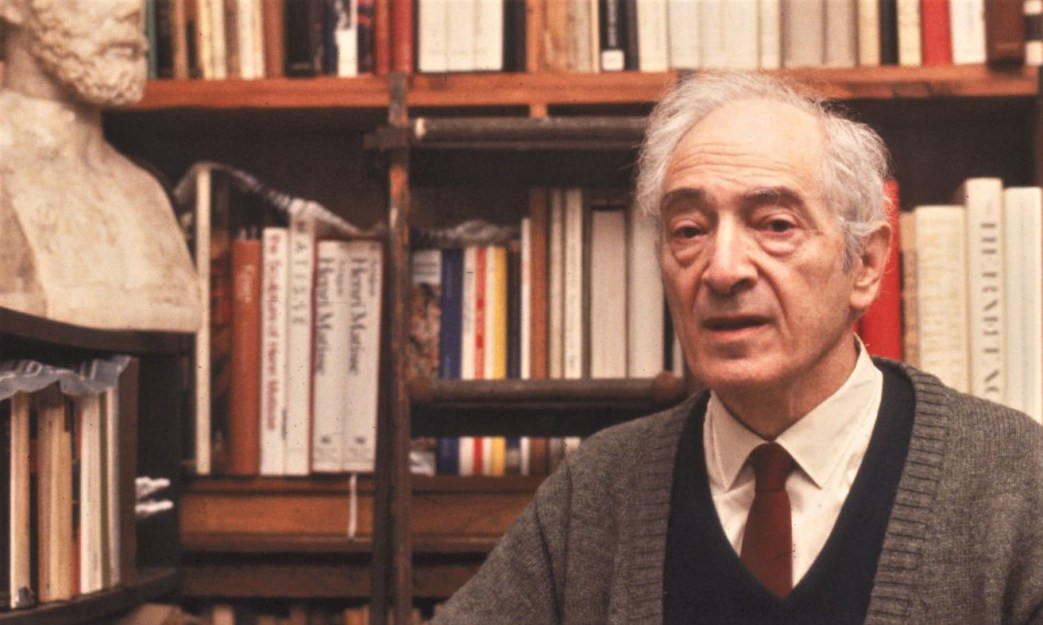

Stimulating reflections from Meyer Schapiro, one of the foremost art critics of the 20th century, who sharply intervenes in a debate that has unfortunately reemerged in all its ignorance and ugliness: What is the role of ‘race’ in the creation of art and what are the consequence of racial notions on cultural production and understanding. Written for the Artists’ Union’s ‘Art Front’ journal.

‘Race, Nationality, and Art’ by Meyer Schapiro from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 4. March, 1936.

MANY artists agree as a matter of course that the art of a German must have a German character, of a Frenchman, a French character, of a Jew, a Jewish character. They believe that national groups, like individual human beings, have fairly fixed psychological qualities, and that their art will consequently show distinct traits, which are unmistakable ingredients of a national or racial style. They assume that French art throughout its long history is distinguished from all of German art by qualities of elegance, tastefulness, formality, which no German can ever acquire, unless he has French blood; and, similarly, they attribute to German art a necessary violence, exaggeration, fantasy, realism and irrationality, which are repugnant to French taste.

Such distinctions in art have been a large element in the propaganda for war and fascism and in the pretense of peoples that they arc eternally different from and superior to others and are therefore, justified in oppressing them. The racial theories of fascism call constantly on the traditions of art; its chief emblems are drawn from ancient motifs of ornament. Where else but in the historic remains of the arts does the nationalist find the evidence of his fixed racial character? His own experience is limited to one or two generations; only the artistic monuments of his country assure him that his ancestors were like himself, and that his own character is an unchangeable heritage rooted in his blood and native soil. For a whole century already the study of the history of art has been exploited for these conclusions.

From such views important consequences are drawn for American art and society. It is taught that the great national art can issue only from those who really belong to the nation, more specifically, to the Anglo Saxon blood; that immigration of foreigners, mixture of peoples. dilutes the national strain and leads to inferior hybrid arts; that the influence of foreign arts is essentially pernicious; and that the weakness of American art today is largely the result of alien influences.

These opinions are only part of a larger view of American society as a whole, a view which condemns Negroes, Indians, Japanese, Mexicans, Jews, Italians and Slavs, as inferior elements, and which justifies their oppression as an economic and cultural necessity of the dominant “race.” As political reaction grows, every argument which supports the notion of fixed racial and national differences, acquires a new relevance. It provokes powerful divisions within the masses of the people, who are becoming more articulate and aggressive in their demands for a decent living and control over their own lives. The basic antagonism of worker toward capitalist, debtor toward creditor, is diverted into channels of racial antagonism, which weakens and confuses the masses, but leaves untouched the original relations of rich and poor. A foreign enemy is substituted for the enemy at home, and innocent and defenseless minorities are offered as victims for the blind rage of economically frustrated citizens. The defenders of existing conditions are enabled to stigmatize as un-American, and therefore useless to the United States, whatever successful efforts the workers and farmers of other countries have made in the struggle for their own well-being. No wonder that the arguments for racial and national peculiarity are supported by the most reactionary groups in America.

But many liberal, and even radical, artists who uncompromisingly reject nationalism, share the belief in fixed racial or national characters in art. It permits an easy explanation of the differences in the arts of modem peoples. It enables one, in ignorance of the complexity of factors which determine the forms of art, to refer the art of a country to a permanent local character, as one refers a single work to the personality of its author. The artist unconsciously supports the very theories which will threaten his artistic independence. He may denounce the view that Negroes and Jews are inherently inferior to Europeans, but he accepts the distinctions between Negro, Italian, German and French art as a matter of permanent psychological traits.

There are Negro liberals who teach that the American Negro artist should cultivate the old African styles, that his real racial genius has emerged most powerfully in those styles, and that he must give up his effort to paint and carve like a white man. This view is acceptable to white reactionaries, who desire, above all things, to keep the Negro from assimilating the highest forms of culture of Europe and America. It is all the more dangerous because it appears on first thought to be an admission of the greatness of African Negro art, and therefore favorable to the Negro. But observed more closely, it terminates in the segregation of the Negro from modern culture. African Negro art is the product of the past conditions of African tribal life. To impose such an art on the modem American Negro is to condemn him to an inferior cultural status. Moreover, the modern Negro, whether African or American, could not possibly reproduce the classical African art; he could turn out only inferior pastiches, like the European fakers who fabricate pseudo-African sculpture for ignorant tourists.

The conception of racial or national constants in art, considered scientifically, has three fatal weaknesses.

In the first place, the empirical study of the art of highly civilized countries during a long period of time has shown beyond question that great historical changes in society are accompanied by marked changes in the character of the arts. Because of the real historical diversity of styles within a single nation, its art cannot be significantly described by a dominant or constant psychological trait; the arbitrariness and empty generality of such far-embracing descriptions (“European art is dynamic, Asiatic art is static, etc.”) are notorious, and only a superficial knowledge of the history of art is needed in order to contradict the commonly accepted generalizations. The tradition of French art is not simply one of elegance and tastefulness or of clarity, order and logic. These vaguely defined qualities emerge only at certain times and under special conditions. In the period from 1830 to 1860 it is France which produces the most realistic and also the most romantic art; there is no German Delacroix, no German Daumier; and the realism of the German schools sometimes takes as his model the work of the Frenchman Courbet. If, between 1905 and 1920, German expressionism is the most vehement and tormented art in Europe, in supposed accord with the German nature, the word for contentment, domestic comfort, untroubled coziness in art is “Biedermier,” a German style of the second third of the fifteenth century. Even the most stable arts, like the Egyptian which is the classic example of cultural immobility, change their expressive character under the pressure of great social and economic changes. The art of Egypt during Byzantine rule, the so-called Coptic art, has little to do with the older Pharaonic art and in the same way the Moslem art of Egypt differs from the preceding Coptic. The presumed racial-psychological characters of an art are developed and transformed historically, and have no known connection with the heredity of a people.

It is true that remarkable resemblances have been found in the modern and ancient arts of a region. But these are not fixed resemblances, due to some intangible property of the blood of the inhabitants of a country. They often proceed from a persisting tradition, or from an a vowed return to the past, as in the copying of Poussin by the neo-classicist artists in France or from a similarity of conditions, purposes, and means, which produced common tendencies in widely separated arts, as in the case of Courbet and the French realists of the 17th century who emanate from the middle class.

In the second place, the character of an art at a given moment cannot be said to reflect the psychology of a whole people or nation; it reflects more often the psychology of a single class, the class for which such art is made, or the dominant class, which sets the tone of all artistic expression. Thus the art of German peasants in the 18th century is more like that of French peasants than the art of German noblemen. And, in turn, the art of German noblemen is closer to that of the French court than the latter is to the art of French peasants. We see in such examples how crucial are the specific social and economic differences, how they obliterate the supposed racial and national constants.

The variety of art within a country and the accord between countries may be described in another way- the arts of the economically advanced countries in Europe today are more like each other than the arts of any one country are like its own mediaeval or Renaissance arts. French “Fauve” painting is more like German expressionist painting than either is like the native art of the 17th century.

During the last hundred years the differences between the styles of a single art, like painting, within a single country, have become very striking, and most striking of all, in the country which has been the undoubted leader in modern art. In 1860, a visitor to Paris could see new works by Ingres, Delacroix, Corot, Daumier, Courbet, Manet, Degas and Pissarro, not to mention the academic painters. In 1936 this variety is even more evident. Nor is it limited to France. In almost every European country we may see side by side examples of academic. classicistic, romantic, realistic, impressionist and abstract art, which are irreducible to a national or racial constant.

There are, of course, qualities in some German paintings today which are less developed in French works, and vice versa. But since these qualities are neither exclusively German nor common to all artists who speak the German language or live in Germany, and since they are not the distinguishing qualities of German art in many periods in the past, it would be wrong to suppose that they are permanent racial characteristics, inherent in German blood. They are due rather to the cultural peculiarities of the country, to peculiarities of tradition and history and the thousand and one continually changing material and social circumstances which form and transform human life.

How the specific local conditions affect the presumed racial character in art is evident enough in the art produced by Jews. The Hebrew ornamented manuscripts of the middle ages are usually in the style of the region in which they were made. In Paris they are Parisian, in the Rhineland, Rhenish, in Venice, Venetian. Even the Hebrew handwriting is affected by the culture of the country. A scholar who is familiar with the styles of Latin writing in Germany and Italy in the 15th century can often tell at once, even if he is ignorant of the Hebrew language and alphabet, whether a Hebrew manuscript comes from Italy or Germany.

In modem times we can observe the same relation in the paintings of Jews. Ruthenstein is an Englishman, Pissarro, a Frenchman, Soutine, a Russian, Pechstein, a German. It is very doubtful that a critic, unacquainted with these painters and ignorant of their work, could judge from any formal detail or pervasive quality of their paintings that they were all produced by Jews.

The writers who try to explain modern art as the evil work of the Jews, attack Jewish intellectualism as the cause of abstract art, Jewish emotionalism as the cause of expressionistic art, and Jewish practicality as the cause of realistic art. This ridiculous isolation of the Jews as responsible for modern art is of the same order as the Nazi charge that the Jews as a race are the real pillars of capitalism and also, at the same time, the Bolsheviks who are undermining it.

The third defect of racial interpretations of art lies within the very concept of race. The idea of a pure race is a myth scorned by honest anthropologists. The distinction of sub-races or physical types within the white race, made by modern scholars, cuts across national lines and contradicts the view that nations are racially distinct from each other or that they are formed of homogeneous groups. The same physical types may be found in Germany and France. But even if there were such correspondences of race and nation or race and culture, there would still be no scientific ground for assuming that each race or ethnic group has distinct psychological characteristics bound up with its physical traits; or that one race is superior, that it has biologically rooted potentialities for culture, not given by nature to others. The differences between the cultures of primitive and civilized peoples today are more adequately explained by differences in natural environment, by historical circumstances, by the effects of favorable and limiting conditions. Psychological tests have revealed no significant inherited inferiority of the so-called backward peoples.

Applied to France, these scientific considerations yield the following result- the art of France is not the art of a homogeneous biological group, with common physical characteristics, but simply the art produced by people of varying ethnic composition within certain political boundaries, more or less shifting. The community of language and customs is constantly mistaken for a community of blood or physical characteristics. The history of the inhabitants of France shows clearly that they were formed by the intermixture of different cultural groups, Celtic, Iberian, Basque, Frankish. Gothic, and the prehistoric peoples of the stone and bronze ages. The products of this mixture show a considerable range in physical traits, corresponding only roughly to geographical divisions. A study of the family origins of the French painters of the nineteenth century shows further that they come of mixed stocks, from various parts of the country. ls there any group more French the nationalist language than the Impressionists? Monet came from Le Havre in the North, Degas was born of a Creole mother and a French father who had one Italian parent, Sisley was born in England of English parents, and Pissarro was a West Indies Jew with a Creole mother.

What unites these artists stylistically is the common culture in which they grew up and produced their art. It is more important to recognize that Monet, Sisley, Degas and Pissarro were the sons of merchants, and that all four painted for Parisian society in the last third of the nineteenth century, than it is to observe the shapes of their skulls or noses or to determine their ultimate racial origin.

If this analysis is correct, then we must denounce appeals for an American art which identify the American with a specific blood group or race, or which identify American art with supposedly fixed and inherent psychological characters inherited from the past. We can only condemn as chauvinistic and cheap a remark like Mr. Craven’s to the effect that Alfred Stieglitz, as a Hoboken Jew, cannot be a judge of American art. By a similar logic, Mr. Craven, coming from a region which has contributed so little to the world’s painting and criticism, should not be taken seriously as a writer on European art.

On the other hand, it is evident that the effort to create art in America will proceed from the conditions of life in this country, conditions which, far from being stable or uniform, are varied and in constant change. The American character is as varied as the American scene. The conception of what is or should be American is determined in the last analysis by the history, tradition, means, interests and mode of life of the different classes in society. For a Southern land-owner, the specifically American is different from that for the Southern mill-owner, different from that for the Southern worker or tenant-farmer, who has become conscious of the disparity between his actual condition and his constitutionally guaranteed “American” rights. The Americanism of the Revolutionary tradition of 1776 and the Civil War is interpreted differently according to the desire of reactionary minorities to restrict liberties, of the masses, to increase or preserve them.

The artist does not apply one color rather than another because he considers it more American; but he is compelled today to take his stand with regard to the Americanism of his art by reactionary groups which, in the name of Americanism, provoke racial and national antagonism, trample on democratic rights, and call on him to serve them or starve. It is in accordance with his own needs, understood concretely and in the broadest sense, embracing his need for freedom, for economic security, and for a genuinely democratic and sympathetic audience, and in accordance with what he considers the most progressive forces in American society, that the artist will form his conception of an American art.

Such an art will be uniform or varied, not because there is only one race or there are many races, but according to the nature of social life-uniform to the degree that social and economic differences have been destroyed, varied to the degree that regional, occupational and individual differences have real liberty of expression.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n04-mar-1936-Art-Front.pdf