A major article on 1905 by Alexander Trachtenberg, a veteran of the Revolution in Odessa jailed for his participation who later emigrated to the United States, written on its 20th anniversary.

‘1905—The Rehearsal for 1917’ by Alexander Trachtenberg from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 2 December, 1925.

LAST month the revolutionary workers throughout the world celebrated the Eighth Anniversary of the victorious proletarian revolution in Russia. Once more workers everywhere gathered to review the year’s achievements and to renew pledges of solidarity with the proletarian and peasant masses of the Soviet Union.

This month two other Russian anniversaries will command the attention of all revolutionists. Both events, which the Russian worker will celebrate, are recorded in the annals of their revolutionary history, one as an episode, the other as an epoch.

The Decembrist Revolt.

The first event was the attempt to de-throne Czar Nicholas I. on December 14, 1825. The plot was engineered by some Guard officers and civilians who, influenced by the ideas of the French Revolution, sought to limit the powers of the Crown through a constitution. The movement was restricted to a few conspirators who were not anxious to establish contact with the masses. Even the soldiers whom the rebellious officers intended to use for the coup were kept in ignorance of their aims and programs, lest these peasant soldiers develop ideas inimical to the interests of the landowning classes to which the conspirators belonged. Nicholas defeated the rebels because on the day of the “uprising” they were still not agreed upon their aims and methods, and because of their failure to organize a popular movement in support of their program.

Viewed from present-day standards, the events of December 14, 1825, may appear only as a revolutionary flare. At the time, the shooting down of the soldiers whom the rebellious officers brought to the Senate Square in Petersburg to demonstrate against Nicholas, the execution of the leading conspirators and the fiendish reprisals of the Czar against all suspected of harboring disloyalty, produced a marked effect. The revolutionary ideas which the “Decembrists” kept to themselves became the heritage of larger groups who came to consider the executed or imprisoned rebels as martyrs. Celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the Decembrist revolt, the Russian workers will draw the proper lesson from the failure of that historic event.

1905—A Revolutionary Epoch.

The second occasion for reminiscence is of much larger proportions. It was not an event of a day; it was a series of events which are recorded in red letters throughout the calendar of that year. Until eight years ago, 1905 stood out pre-eminently as an epoch-making year in the history of revolutions. In the nineteenth century only 1848 and 1871 could compare in revolutionary significance with 1905. The revolution of 1905 was not only the rehearsal for 1917, but it had affected the political destinies of many peoples. The popular movements for wider suffrage in Austria and Belgium; the revolutions of Persia, Turkey and China, were some of the outstanding events which took place during the revolutionary era inaugurated in 1905.

The Background of 1905.

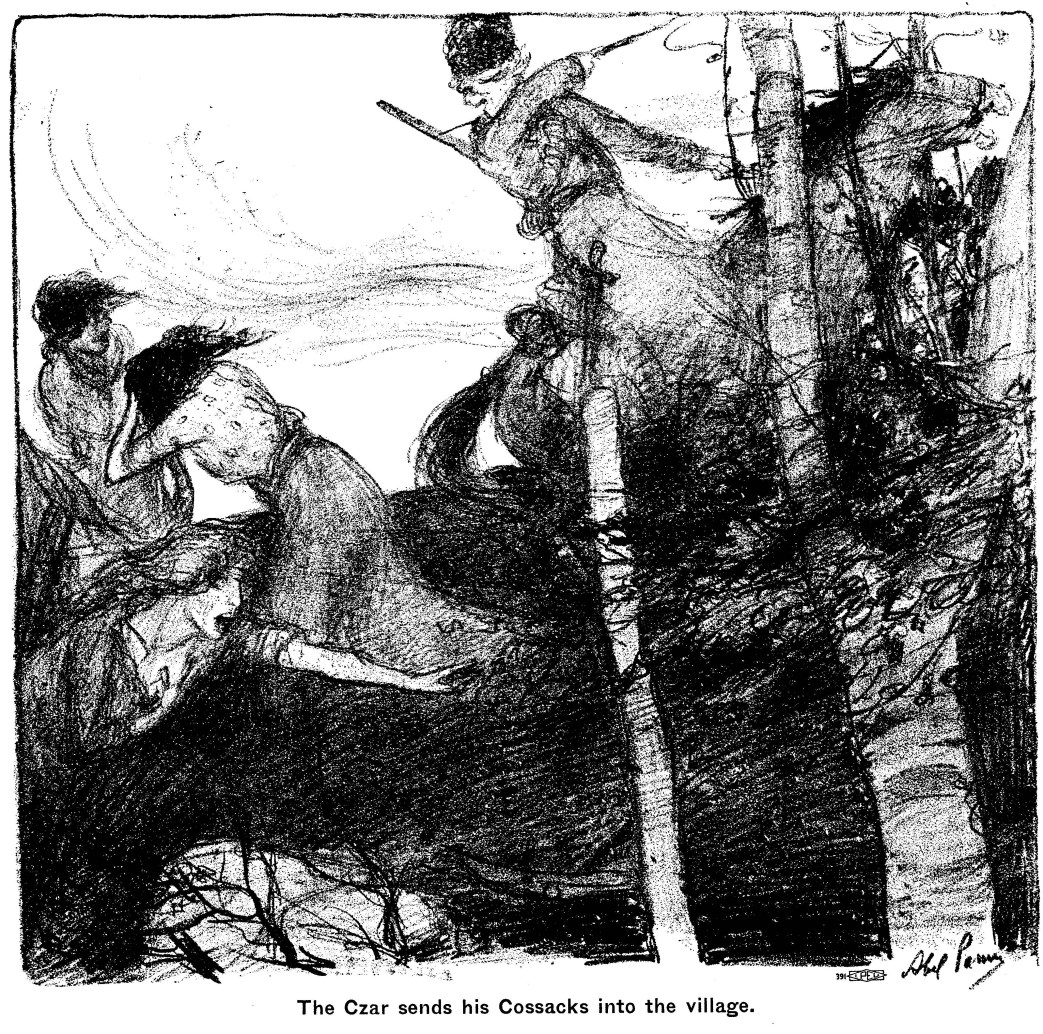

Nineteen hundred and five was the cumulative effect of sporadic and isolated revolutionary outbreaks of preceding years, particularly those beginning with 1900. The landless and poor peasants who were suffering on account of the transition from the feudal to the capitalist methods in agriculture and were groaning under heavy tax burdens, were rising against the landlords, setting fire to estates and expropriating agricultural products and machinery. Between 1900 and 1905, nearly seven hundred outbreaks occurred in different parts of the country, which brought punitive military expeditions to the villages and helped further to widen the breach between the peasantry and czarism.

The sporadic strike movements in the cities were affecting more and more workers. Long hours (twelve to fourteen); low wages (six to eight dollars a month); intolerable conditions of employment, mistreatment by foremen, prohibition of labor unions, drove the workers to resort to strikes, which, however, were usually broken with the aid of the police and Cossacks. It is estimated that during the five years prior to 1905, over 200,000 industrial workers were affected in these strikes. The socialists, though as yet small in numbers and only beginning to gain a foothold among the masses, were utilizing the strikes and the government interference in behalf of the employers in the attempt to turn the economic outbreaks into political demonstrations against the government.

The Police Unions.

To cope with the growing influence of the Socialists among the workers the government decided to permit the formation of benefit organizations and even promised to intercede in their behalf with employers in order to reduce their wages a bit, and working somewhat the working day, raise their wages a bit, and remove some of the objectionable conditions.

These organizations, in fact, were formed under the aegis of the government, and are known in Russian labor history as Police Unions.

These “labor unions” were to be the Russian counterpart of the unions existing in West-European countries—namely the Hirsh-Dunker the Catholic unions of Germany, Austria and Belgium, and similar de- revolutionized labor organizations. Instead of yellow unions, as they are known in other countries, the czarist government was going to have them altogether black. Mussolini took a leaf out of Russian history when he formed his fascist labor unions. This, however, is not the only resemblance that bears his regime to the czarist order of old Russia.

Zubatov, the chief of the secret police in Moscow, became the organizer of such unions, in which he succeeded in enrolling large numbers of workers. Siding with the workers on a few occasions in their conflict with the employers, Zubatov gained an influence and for a time proved the efficiency of unions organized under government patronage. During the celebration at the monument of Alexander II. in 1902, Zubatov was able to corral about 50,000 workers.

Under Zubatov’s tutelage, similar “labor unions” were organized among the workers of Odessa and Minsk, where renegade Socialists became the willing aides of the Moscow chief spy. Zubatov was particularly anxious to win the Jewish workers who started earlier in forming illegal labor unions. His endeavors among them met with little success from the very start.

Large numbers of workers in Petersburg were later inveigled into joining these police unions. As in Moscow, the Socialists warned the Petersburg workers against joining these organizations, pointing out their true nature and purpose, but some of the immediate results, mostly irrelevant, which they had secured through them, and particularly the right to assemble at their factory clubs to discuss matters of mutual interest, proved more convincing at the time. It was in these organizations that the priest Gapon, who was later destined to play a historic role, was active in educational and other capacities. Gapon’s direct contact with the police was not known then. He was looked upon as a peculiar character with a burning ambition for leadership.

The Russo-Japanese War.

The government had imperialist designs of extending its domains in the Near and Far East. On February 16, 1903, General Kuropatkin said to the future Count Witte: “Our emperor carries around great plans in his head. He wants to take Manchuria, annex Korea and Tibet, occupy Persia, and secure not only Bosphorus but the Dardanelles as well.” (Quoted by Professor Pokrovsky from Witte’s Memoirs.— A.T.) In 1901 Nicholas informed Kaiser Wilhelm, whom he met in Danzig, that he was preparing to fight Japan. In 1903 he again told Wilhelm about the impending conflict with Japan, but was sure that he would be the one to choose the time.

The concessions of Admiral Bezobrazov on the Yalu river, in which some members of the royal family were interested and which Japan considered as preparatory to the occupation of Korea, were the immediate casus belli. Japan, however, knew of Russia’s designs and didn’t care to wait till Nicholas would decide when it would be most convenient for him to strike. Japan opened hostilities and found the Russian government prepared only on blue prints, and even those were faulty. Since it has always been the practice of governments to inaugurate a “vigorous foreign policy,” i.e., start a war somewhere, when pressed by internal troubles, and since the Russian government was planning to fight Japan some day for the supremacy in the Far East, Japan’s ultimatums were not heeded and Russia entered upon a war which contributed a great deal to the Revolution of 1905. Kuropatkin’s continuous “orderly” and “strategic” retreats with great losses of killed and wounded, constant lack of ammunition and supplies when needed, graft scandals, quarrels between various military and court cliques, orgies and debauchery among the commanding staff, and reports of peasant and labor disturbances at home, contributed a great deal to the revolutionizing of the soldiers at the front.

The Bourgeoisie and the Revolution.

The war in the Far East helped to expose the inherent weakness of the czarist regime. Not only were the revolutionists hoping for a complete humiliation of the much advertised Russian military prowess, but even the liberal bourgeoisie was evincing distinct defeatist tendencies. The defeat of the government at the front, it was expected, would undermine its prestige at home and abroad. The objectives of the bourgeoisie included then a weakening of the influence of the feudal aristocracy in the government. This could be achieved by a crushing defeat in the Far East at the hands of Japan and by continuous disturbances at home organized by the revolutionists. The burning of estates by the peasants, the outbreaks in the cities led by workers and students, and even the terrorist acts against high government officials (Ministers Bogeliepov, Sypiagin, and Plehve) were applauded by the bourgeoisie. It was at that time that Milyukov was continually referring to “our friends on the left.”

It is claimed (Professor Pokrovsky) that in some cases employers did not object to strikes, particularly if they showed a tendency to develop into political demonstrations, and embarrassed the government. Some employers even helped their workers to tide over during the strikes so that the strikes could be prolonged. The young capitalist bourgeoisie was having visions of an approaching revolution like the revolution of 1848, when the workers would go forth to fight the entrenched feudal aristocracy in their behalf.

The Mensheviks fell a prey to the flirtations of the bourgeoisie with the revolution. The questions of properly evaluating the role of the bourgeoisie during the revolutionary period and of the attitude of the Socialists towards it, were the first important differences which arose between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks after the second Party Congress of 1903, when these factions were formed. When the bourgeois liberals began actively to organize their Zemstvo and other public campaigns in 1904, the Mensheviks proposed that the workers participate in those movements and support the bourgeoisie in its effort to undermine czarism.

The Menshevik “Iskra” wrote then: “When we survey the arena of struggle in Russia, we perceive only two forces: the czarist autocracy and the liberal bourgeoisie which has already constituted itself and is a power to be reckoned with. The laboring masses are divided and can accomplish but little. We do not independent force and our aim therefore should be to support the other force— the liberal bourgeoisie, to support and encourage it and under no circumstances attempt to scare it with our independent proletarian demands.” (Quoted by G. Zinoviey in his “History of the Russian Communist Party.” The American Socialists, in thorough Menshevik fashion, have adopted this policy for the United States, and have “justified” it in about the same language.)

The Bolsheviks attacked the proposed policy of self-effacement. To deny the existence of the worker as a moving revolutionary force was considered by Lenin tantamount to a capitulation and turning over of the workers to the service of the bourgeoisie. The Bolsheviks admitted revolutionary aims on the part of the bourgeoisie at that time, but they proposed that the workers utilize them rather than the other way around, as the Mensheviks wanted to do. The Mensheviks never recovered from that original sin and during their later career they sank deeper and deeper in the mire of bourgeois collaboration and disbelief in the creative forces of the proletariat.

“Bloody Sunday.”

The year 1905 opened with the Russian armies still retreating “in orderly fashion” in Manchuria, and with the government trying to disguise its autocracy through the liberal (sic!) regime of Prince Sviatopolk-Mirksy who was called to power after a couple of ministers were despatched to their forbears by the bomb route. Mirsky’s entrance into the government was advertised as the beginning of a new era—a “Spring” after the cold and dreary Winter under the late but unlamented von Plehve. It was during this “Spring” regime, when the government was supposed to have reformed, and officially foreswore any excesses, that the first act of the revolutionary drama of 1905 took place. Decreed by the fate of the Revolution, the workers who were under Gapon’s tutelage and government protection, were chosen to be the performers in that first act.

It began with a strike at the Putilov Mills. The strike was conducted by the Society of Factory Workers—the Petersburg police union, with economic demands as the original cause. The leaders of the Society and of the strike who were employed at Putilov’s were discharged by the administrators. Sympathetic strikes followed, first in different parts of the Putilovy workers and later spreading to the factories until they embraced about 140,000 workers.

It was then that the grandiose plan to present the czar with a petition was put forth. Gapon, sensing a dramatic opportunity for himself, urged this plan upon the masses of striking workers who were getting beyond control, The Socialists tried hard to dissuade the workers from adopting the plan. They warned the workers not to go into the trap which the government was spreading for them. But it was of no avail. Gapon and his lieutenants had the control over the masses. The petition was drawn, in which, in humble and pious language, the Little Father was importuned to take pity on his suffering children and improve their miserable lot. Not being able to stop the proceedings, the Socialists tried to introduce some political demands into the movement upon which they looked with apprehension.

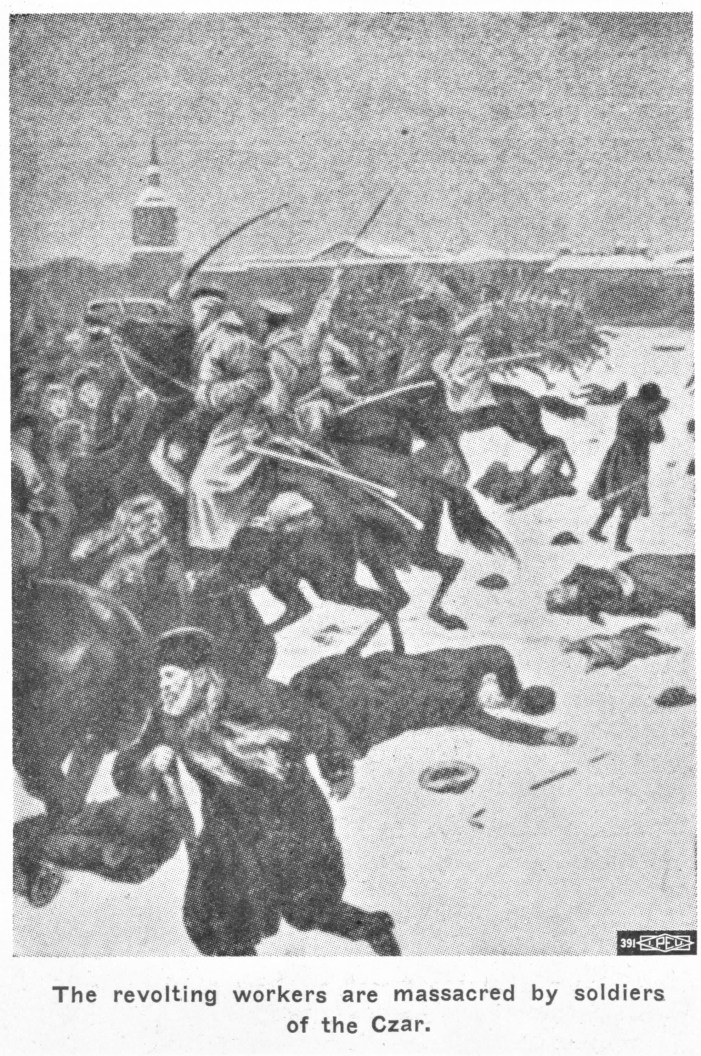

Gapon organized the parade to the Winter Palace in grand style. He got thousands of workers—men, women and children—to join the procession with church ikons and portraits of the czar carried at the head, attesting to the religious and political reliability of the masses. The parade was set for Sunday, Jan. 22. Gapon claimed that he had notified the Minister Mirsky about the intended presentation of a petition to the czar at the Winter Palace. When the procession reached the square in front of the palace, it was met, not by the Little Father, but by his picked soldiers, who sent a volley of shots into the crowd, with the result that thousands lay killed and wounded on the snow covered stones, before the masses could realize what had really happened.

The government knew of the proposed manifestation and petition. It knew the contents of the document, which was devoid of any revolutionary sentiments. The petition was full of humility and resignation. It ended as follows:

“These, Lord, are our main needs which we want to call to your attention. Decree and swear to carry them out— and you will make Russia glorious and powerful; you will imprint your name on our hearts and the hearts of our progeny forever. If you will not accept our prayers, we shall die here on this square in front of your palace. We have no place to go to, and there is no purpose in it. We have only two ways, either to liberty and happiness, or to the grave. Point out, Lord, either one and we shall go to it without protest, even if it shall be the way to death. Let our lives be the sacrifice for suffering Russia. We are prepared to make this sacrifice. We shall gladly make it.” (Quoted in L. Trotzky’s “1905”).

The butchery was a clear provocation on the part of the government. The workers were fooled into the undertaking so that the government might administer a “rebuke” which would be remembered by all those who might want to embark on a similar course of action. The murder on Palace Square was the apotheosis of the “Spring” regime. The autocracy bared the claws which it has kept hidden, and served notice on the people that it would brook no opposition, nor even loyal prayers for partial reform. Governor Trepov’s orders to the Petersburg garrison “not to be niggardly with bullets” was the defiant answer of the czar to the approaching revolution.

The Revolution Is Born.

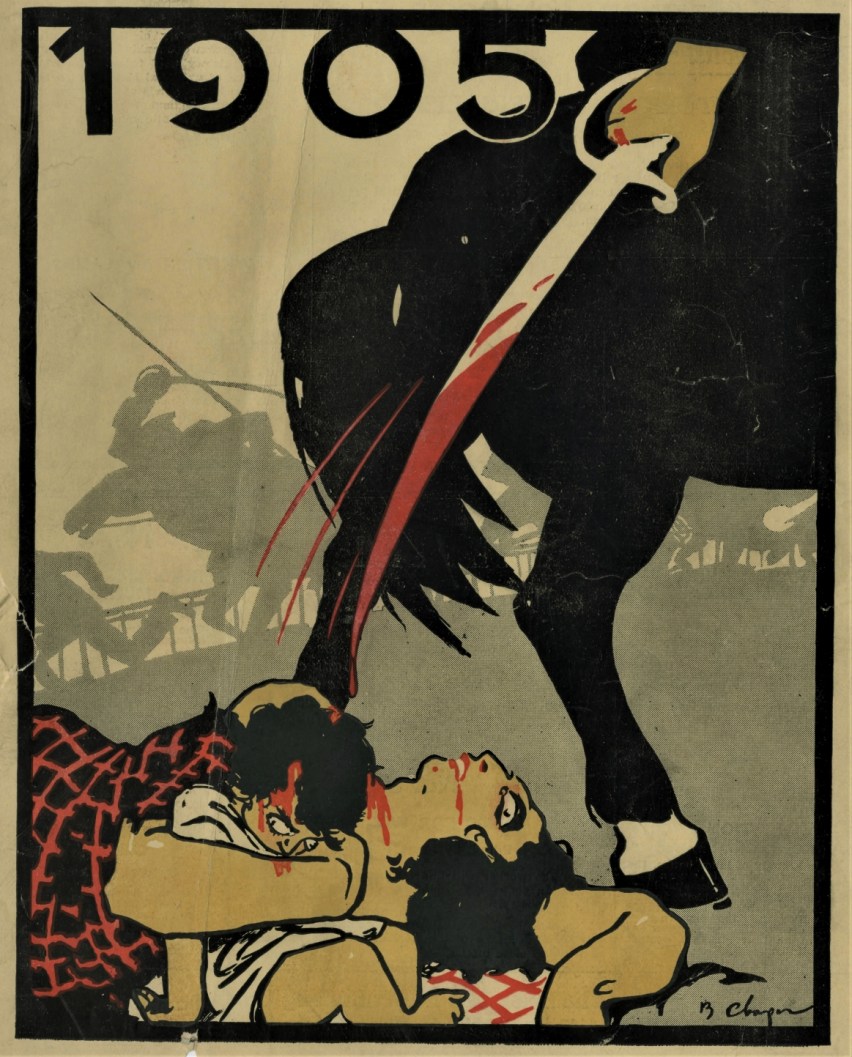

Almost two generations of revolutionists have come and gone before January 22, 1905. Many of them have swung from the gallows and still more were buried alive behind prison walls, or were laboring in Siberian mines for having dared to dream about a rising of the people against autocracy. Bloody Sunday opened the flood-gates of the revolution. The fiendish betrayal of the masses on the Palace Square destroyed in the Petersburg workers every vestige of trust in the “Little Father” and his government. They entered the square humble and servile subjects of the czar. Those who remained alive left the Square with their minds cleared of the age-long illusions and with a consuming vengeance in their hearts for the murder of their fellows.

Not only in Petersburg, but in all industrial centers, a revolutionary class began to assert itself, realizing the conditions under which it was living and conscious of its power to alter those conditions. The blood of the murdered Petersburg workers cried out for revenge and action, and the workers everywhere rose in a mighty protest against the crime perpetrated upon their class. During the following month one hundred and twenty-two cities were in the throes of strikes and political demonstrations of workers.

It was while these events were taking place that the crafty Witte was writing Nicholas to end the war with Japan because of lack of funds, and because “we need the army in Russia to fight our own people.” The Moscow workers were none too gloomy when they heard on February 4 that Grand Duke Sergius, the czar’s uncle, was blown to bits in front of the Kremlin. Outbreaks were occurring everywhere. The peasants were also rising against the landowners and the government which was squeezing the very lifeblood out of them. In the army, particularly in the fleet, unmistakable signs of revolts were being observed. During the summer, when it looked as though the government had succeeded in arresting the disturbances, the sailors on the battleship “Potemkin” of the Black Sea fleet, rose in revolt and attempted to get the rest of the fleet to follow their example. This rebellion frightened the government, and it made public a proposal of one of its ministers to establish a parliament with consultative powers to which only representatives of the capitalists and landowners could be elected. This proposal for a parliament was met with derision everywhere and nothing came of it. The middle particularly the professionals—teachers, lawyers, office workers, engineers, etc., were also being drawn into the welter of the revolution. Organizations of these elements were being formed and national conventions were held in which sympathies with the aims of the revolution were expressed. The revolution was beginning to penetrate all sections of the population. While it was broadening out it was also striking its roots deeper into the social fabric.

Revolutionary Theory and Revolutionary Action.

The revolution was marching in seven league boots. The Social-Democratic party was the leading political factor in the revolution. The Socialist-Revolutionists had little influence among the workers. Among the- Social-Democrats the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions, though in the same Party, were developing different ideas regarding the various problems affecting the revolution. The Mensheviks were in control of the Central Committee of the Party. Immediately after January 22, the Bolsheviks began to demand the convocation of a Party congress to analyze what had happened and chart of the course for future actions. The Mensheviks refused and the Bolsheviks issued a call for a congress which was held in London. No Menshevik delegates came to the Congress, this faction having called a conference of its own people in Geneva. Since the majority of the Party organizations were represented at the London Congress it was considered as a regular Party Congress. The Mensheviks never accepted that. This was really the first Bolshevik Congress at which a homogeneous group gathered to evaluate the changes in the conditions of the country and the ideology of the workers. It was the most significant congress in the history of the Party. It laid the foundation for the most important policies, which later marked the Bolsheviks as a distinct group in the Socialist movement. Most of the best-known Bolshevik leaders participated at this Congress— Lenin, Kamenev, Rykov, Lunarcharsky, Krassin, Litvinov, Vorovsky and others were there to formulate the policies which not only were carried out during the 1905 revolution but were at the basis of the revolutionary activity of the Bolsheviks up to and during 1917.

While the Mensheviks were already getting scared that the revolution was going a bit too fast, the Bolsheviks were boldly and optimistically looking forward to the natural unfolding of the revolution in which the Russian workers were destined to cover themselves with glory. It was at this Congress that the Lenin formulation of the dictatorship of the workers and peasants was adopted.

Only a chance discussion of democracy took place at the previous Congress. This discussion became historic, because Plekhanov sided with Lenin in the analysis of the attitude of the proletariat toward democracy.

A Bolshevik delegate, Pasadovsky, raised the following question while some editorial changes of the program were being adopted: “Shall our future policy be subordinated to this or that fundamental democratic principle, or shall all democratic principles be subordinated entirely to the advantage of our Party,” and continued: “I am for the latter position. There is no democratic principle which shouldn’t be subordinated to the welfare of the Party.” Plekhanov replied by expressing solidarity with Posadovsky’s position. It is worth while quoting his opinion somewhat at length on this very important point. It would be well for our American Socialists who are enamoured of democracy to read carefully the following lines:

“Every given democratic principle,” said Plekhanov, “must be considered not as an isolated proposition, but in relation to that principle which can be called the fundamental principle of democracy—salus populi suprema lex— (the welfare of the people is the supreme law). Translated into the language of a revolutionist it means that the success of the revolution is the supreme law. If it were necessary for the sake of the revolution temporarily to limit the operations of this or that democratic principle, it would be criminal to question such limitations. My personal view is that even the principle of universal suffrage can be looked upon from the democratic principle just enunciated by me. It can be hypothetically conceived that we, social-democrats, may declare against universal suffrage. The bourgeoisie of the Italian republics sometimes denied political rights to members of the nobility. The revolutionary proletariat could limit the rights of the upper classes in the same way as the upper classes limited its rights. The worthiness of such a measure could be considered entirely from the rule—salus revolutiae suprema lex.”

The draft program carried a provision for the election of parliament every two years. In discussing this provision in connection with the whole question of democracy, Plekhanov said: “The same point of view should prevail regarding the question of the duration of parliament. If the people, imbued with revolutionary enthusiasm, elected a very good parliament, it would be our duty to make it a long parliament. If, on the other hand, the elections proved unfavorable we should try to disperse it, not within two years, but within two weeks.” (Quoted from Report of Second Congress of the Russian Communist Party.)

These golden words, coming from the father of Russian Marxism, were enthusiastically acclaimed by Lenin and his followers, who left this Congress nick-named “Bolsheviks.” When Zinoviey writes about this period of Russian Party history, he cannot refrain from speaking about the “Bolshevik Plekhanov.”

The Third during the Revolution. It not only formulated the theory of workers’ and peasants’ dictatorship, but raised the slogan for an armed uprising as the only means of carrying the revolution to a favorable conclusion. The relation to the existing government on the eve of its overthrow, the attitude towards the provisional government which would come in its place, and toward the bourgeoisie, were among the important policies adopted at this Congress which was sitting as a revolutionary war council.

The General Strike.

The General Strike in October was the natural outcome of the strike movement which was gaining momentum during the year. The political character of these strikes became their dominant feature and the workers began to look upon the isolated stoppages as preludes to greater demonstrations.

A general strike was originally contemplated for January, 1906, when the so-called Bulygin Duma, referred to above, was to convene. The railway workers of the Moscow district began to strike October 20, with a view to testing their strength. Other districts followed. In the meantime, demands for the 8 hour day, amnesty for political prisoners, and civil liberties were being advanced. The strikes began to spread and to affect not only the railway workers all over the country, but other industries as well. Within one week the strike became general. Economic life was paralyzed as a result in all industrial centers. After trying to liquidate the strike by the force of arms in several cities, the government admitted its defeat and “granted,” on October 30, a constitution with the promise to convene a parliament. Although the civil liberties granted in the Manifesto remained on paper, and the Duma was a restricted legislative assembly, the capitulation of the government proved the power of the general strike employed for political purposes.

The liberal bourgeoisie declared itself completely satisfied with the October Manifesto. They wanted a share in the government and the constitution gave them that. They were anxious to see the strike liquidated. In this they were Supported by the Mensheviks and some labor unions who were afraid that the strike might go “too far,” and endanger its achievements. The Bolsheviks insisted on the continuation of the struggle and counselled further preparations as the enemy was not entirely beaten. Within three days of the calling off of the strike, the government, in league with the so-called Black Hundreds organized a come-back. The counter-revolution stalked through the land in the form of Jewish pogroms organized simultaneously in over 100 cities. Playing upon the religious prejudices of the ignorant and superstitious people, hired bands of criminal elements proceeded under police protection to pillage and massacre Jews, aiming in this manner to terrorize the population. Under the cover of these instigated disturbances the government was preparing to liquidate the revolution.

The Soviet is Formed.

While the general strike marked an epoch not only of the Russian Revolution but of the international labor movement as well, it fell on a by-product of this strike to become the single outstanding contribution of the revolution. When the general strike was spreading in Petersburg it became evident that a body would have to be formed to take charge of the conduct of the strike and exercise other functions which the exigencies of the moment might demand. There were two revolutionary parties which were appealing to the laboring masses:—the Social-Democratic and the Social-Revolutionary. In addition, the first was divided into two distinct groups which to all intents and purposes were functioning as separate parties. No single political group could then claim complete control, though the Bolsheviks were the most active driving force. It was also thought advisable that the workers directly from the shops and factories be drawn into the administration of the strike. It was then that the idea of a delegated body of workers representing all striking establishments was formulated. Between October 23 and 26 about forty delegates were chosen who assembled in the Technological Institute and constituted themselves the Petersburg Soviet of Workers’ Deputies. The basis of representation was one deputy to every 500 workers. The Soviet elected an Executive Committee upon which the revolutionary political parties were represented.

The first meeting of the Soviet issued a manifesto in which it called upon all workers to stop work and elect delegates to the Soviet. “The working-class chose the final powerful weapon of the international labor movement—the general strike,” the manifesto informed the workers after reciting the reasons for the strike. It also warned the workers that “in the immediate future Russia will witness decisive events that will determine the fate of the workers for many years. United in our common Soviet we must be prepared to meet these demands.” Although less than a year had passed since Bloody Sunday, the workers had learned to speak a different language than they used in January under yapon. Not only the industrial workers, but clerks, teachers, engineers and other professionals were represented in the Soviet. The Soviet became the center of all strike activities. Although within the framework of the Czarist regime, the Soviet became the labor parliament, and the workers began to look upon it as their class government. It not only dealt with problems arising within the labor movement and conducted the strike, but it became the spokesman of the workers in their relation with the outside world. Following the Petersburg example, other industrial centers organized Soviets which took charge of the strike situation.

When the Czar issued his manifesto on October 30, the Petersburg Soviet countered with a declaration: “The workers don’t want the knout even though wrapped in a constitution.” The Soviet served notice on the government that only its complete destruction would satisfy the workers. The Soviet continued to function when the counter-revolution raised its head. The defeat of a provoked uprising of the Kronstadt sailors, the state of siege declared in Poland, and in many industrial centers, was met by the declaration of another strike on November 13. Notwithstanding that it was only two weeks after the general stoppage, the workers answered the call of the Soviet, and the strike which lasted seven days forced the government to recall the court martial proceedings against the revolutionary Kronstadt sailors.

On December 8 the Chairman of the Soviet, Chrustalev Nosar was arrested. The Soviet continued to carry on under the leadership of the Presidium of three delegates, one of whom was Trotzky. It was only after the arrest of the Chairman, that the Soviet began to consider decisive action. In a resolution dealing with Nosar’s arrest, the Soviet declared in favor of continuing and “to prepare for armed insurrection.” By this time the revolution was already at a low ebb.

The Petersburg workers had gone through two general strikes within three weeks and the unsuccessful attempt to establish the 8 hour day by revolutionary means after the November strike, had further dissipated the energies of the workers. The decision to prepare for an armed uprising came too late. Within a week after the Chairman’s arrest, the government considered itself strong enough to order the arrest of the entire Soviet. The defeat of the Moscow uprising gave the government courage to take this step in Petersburg.

The Petersburg Soviet existed fifty days, from October 26 to December 16, and during this time the government was forced to allow it to function openly in one of the public buildings. The Soviet was representative of the entire laboring population of Petersburg. It consisted of 562 delegates and represented over 200,000 workers. The delegates came from 147 factories, 34 shops, and 16 trade unions. Representatives of the Social-Democrats and Socialist-Revolutionists served on the Executive Committee of the Soviet. The Soviet published an organ—the “Izvestia””—which reported all activities and proceedings of the Soviet.

The Moscow Uprising.

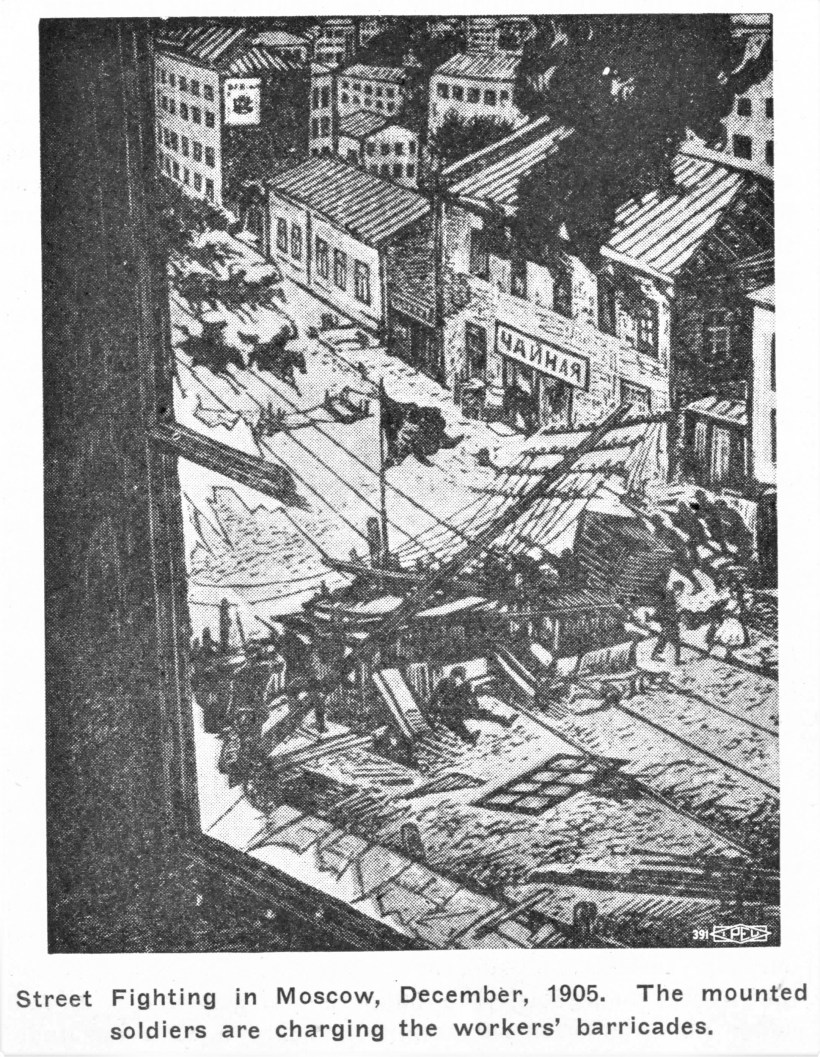

The Moscow Soviet was led by the Bolsheviks, though the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionists were represented there. Following the third Congress of the Party described above, the Moscow Bolsheviks developed an energetic campaign for a more resolute policy than was practiced in Petersburg. Armed insurrection as a means of the revolutionary struggle was advocated among the workers and armed units were formed in different factories under the supervision of the Bolsheviks. As the counter-revolution was spreading, the Moscow Soviet called for a political strike on December 7 “aiming to develop it into an armed uprising.” As the Moscow garrison was unreliable, a loyal Guard regiment was sent from Petersburg as a punitive expedition to clear the city of revolutionists. Troops were ‘brought from other cities. The Moscow workers accepted the challenge, and for ten days they fought like lions an enemy far superior in numbers, ammunition and training. The instructions of the military commanders to their soldiers were not to arrest any revolutionists but to kill them on sight. When a bomb was thrown from some house into a detachment of soldiers, orders came to fire the house, irrespective of the fact that there were women and children and others who may have had no relation to the uprising. One proletarian section, Presnia, particularly distinguished itself. Barricading themselves in the yards of the Prochorov textile factory the small armed force held the Guard regiment for several days. When they realized that they would have to give up fighting, they retreated in orderly fashion and, covered by the sympathetic workers, were soon outside of the environs of Moscow.

The military expedition was successful in putting down the uprising. Not only the government but the bourgeoisie breathed freely. The Moscow uprising gave them the greatest scare. If they had any sympathy for the revolution prior to the December uprising, they quickly parted with it, and were grateful to the government for its determined action in Moscow. And Plekhanov, too, joined the chorus by declaring that “this (the defeat) was not difficult to foresee and therefore there should not have been a resort to arms.” Lenin, on the contrary considered the Moscow uprising as a highly important achievement of the revolution. He recalled Marx’ letters to Kugelmann written during the French Commune in which the latter glorified the “storming of the heavens” by the Paris workers.

The Lessons of 1905.

If the Russian workers were born as a revolutionary class in Petersburg, it was in Moscow that they came of age. The Russian Revolution began after Bloody Sunday: it reached its highest form during the December uprising in Moscow. During 1905 the Russian working-class had Tun the whole gamut of revolutionary action. The Mensheviks considered the defeat of the 1905 Revolution as irreparable. They counselled new methods, peaceful and democratic, to avoid sacrifices in the future. They proposed the liquidation of the underground movement and favored coalition with the bourgeoisie which was going to function within the framework of the October constitution. The Bolsheviks on the other hand were not down-hearted. They counted the losses during the counter-revolution. They saw numerous mistakes which were made, but they realised that during the revolution, during the “storming of the heavens,” the Russian workers became conscious as a revolutionary class which was destined to assert its revolutionary will in Russia. While the Mensheviks were engaged in funeral rites over the revolution, the Bolsheviks maintained that Czarism won only a Pyrrhic victory; that the revolution only retreated to reorganize its broken lines and to prepare itself for new action when the opportune moment arrived. Instead of calling off the struggle, as the Mensheviks proposed, the Bolsheviks threw into the teeth of the government the defiant declaration that the revolution had only begun, and that it would continue until every vestige of autocracy and capitalism was destroyed. The Bolsheviks put themselves at the head of all those elements of the working-class who had faith in the living forces of the revolution, notwithstanding the defeats and even temporary demoralization.

During the years of reaction which followed (1906-1917), the Bolsheviks were studying every phase of the revolutionary occurrences of 1905. All the major policies and tactics which were utilized during the stormy days of 1917, were in the main based on the experiences of 1905. The old revolutionary Plekhanov formula stated by him ten years before 1905 that “the Russian Revolution will win as a workers’ revolution or it will not win at all,” was improved by the Bolshevik amendment, including the peasants as a factor in the Revolution, The tremendous revolutionary effect of the peasant uprisings did not contribute as much as they might have to the 1905 revolution because they were isolated and apart from the occurrences in the cities. The Bolsheviks saw the need for a link between the two basic forces of the revolution—the exploited workers and peasants, if the revolution was to be victorious. The slogan “All Power to the Soviets” raised by the Bolsheviks immediately after the March, 1917, revolution, was the natural result of the experiences with the Soviets which came into being during the general strike of 1905. The betrayal of the 1905 revolution by the liberal bourgeoisie taught the Russian workers the lesson to share the revolution only with the peasants—their natural allies. Even Kautsky, when he was still a Marxist, wrote in “The Road to Power” in 1909—a work inspired by the 1905 revolution, in favor of the Bolshevik attitude towards the bourgeoisie.

He was sure that coalition with the bourgeoisie “can only compromise a proletarian party and confuse and split the working-class.” Kautsky, who then still knew his Marx and Engels, referred to the authority of the founders of scientific socialism to prove his contention. “However willing Marx and Engels were to utilize the differences between capitalist parties towards the furtherance of proletarian purposes, and however they were opposed to the expression ‘reactionary mass’ they have, nevertheless, coined the phrase ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ which Engels defended shortly before his death in 1891, as expressing the fact that only through a purely proletarian political domination can the working lass exercise its political power.” (Quoted from A.M. Simon’s translation of “The Road to Power.” In his translation Simons rendered the word ‘Diktatur’ into ‘dictation’ instead of ‘dictatorship.’ A. T.).

The attitude toward democracy which Plekhanov formulated yet in 1902 and which we quoted above, the Bolsheviks carried out in toto. Following Plekhanov’s advice, they sent the Constituent Assembly, which included Plekhanov’s followers, home “because the election proved unfavorable” to the interests of the revolution, and as Plekhanov said: “Salus revolutiae suprema lex.”

The armed attempt to seize power on November 7, 1917, proved successful, because the Bolsheviks had the armed uprising of December, 1905, as an example.

The revolution of 1905 made the victorious revolution of 1917 possible, for as Lenin said: “1905 was the general rehearsal for 1917.”

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v5n02-dec-1925.pdf